Aeolus (son of Hippotes)

In Greek mythology, Aeolus,[1] the son of Hippotes, was the ruler of the winds encountered by Odysseus in Homer's Odyssey. Aeolus was the king of the island of Aeolia, where he lived with his wife and six sons and six daughters. To ensure safe passage home for Odysseus and his men, Aeolus gave Odysseus a bag containing all the winds, except the gentle west wind. But when almost home, Odysseus' men, thinking the bag contained treasure, opened it and they were all driven by the winds back to Aeolia. Believing that Odysseus must evidently be hated by the gods, Aeolus sent him away without further help. This Aeolus was also sometimes confused with the Aeolus who was the son of Hellen and the eponym of the Aeolians.[2]

Family

All that Homer's Odyssey tells us about Aeolus' family is that his father was Hippotes, that he had six sons and six daughters, that Aeolus gave his six daughters to his six sons as wives, and that Aeolus, his wife, and all their children lived happily together on the idyllic island paradise of Aeolia.[3] In Euripides' lost tragedy Aeolus, one of Aeolus' six sons is named Macareus, and one of his six daughters is named Canace (also the name of one of the five daughters of Aeolus son of Hellen).[4]

The Byzantine poet John Tzetzes (c. 1110–1180) gives the following names for Aeolus' children: the sons Periphas, Agenor, Euchenor, Klymenos, Xouthos and Macareus, and daughters Klymene, Kallithyia, Eurygone, Lysidike, Kanake and an unnamed one.[5]

Mythology

Ruler of the winds

According to Homer, Aeolus the son of Hippotes was the king of the floating island of Aeolia, whom Zeus had made the "keeper of the winds, both to still and to rouse whatever one he will."[6] In Apollonius of Rhodes's Argonautica, at the request of Hera, he calmed all the winds but the "steady" west wind, to aid Jason and the Argonauts on their journey home.[7]

In Virgil's Aeneid, Aeolus keeps the winds contained in a cave on Aeolia:

There closely pent in chains and bastions strong,

they, scornful, make the vacant mountain roar,

chafing against their bonds. But from a throne

of lofty crag, their king with sceptred hand

allays their fury and their rage confines.[8]

Because of her hatred of the Trojans, Juno (the Roman equivalent of the Greek Hera) pleads with Aeolus to destroy Aeneas' ships, promising to give Aeolus the nymph Deiopea as wife.[9] So Aeolus unleashed his winds against Aeneas.[10] But Neptune, angry at this usurpation of his sovereignty over the sea, commands the winds to:

... Haste away

and bear your king this word! Not unto him

dominion o'er the seas and trident dread,

but unto me, Fate gives. Let him possess

wild mountain crags, thy favored haunt and home,

O Eurus! In his barbarous mansion there,

let Aeolus look proud, and play the king

in yon close-bounded prison-house of storms![11]

Neptune then quelled the monstrous waves that Aeolus' winds had stirred up, and Aeneas was saved.[12]

Encounter with Odysseus

In Homer's Odyssey, Odysseus and his men, after escaping from the Cyclops Polyphemus, came next to the island of Aeolia:

where dwelt Aeolus, son of Hippotas, dear to the immortal gods, in a floating island, and all around it is a wall of unbreakable bronze, and the cliff runs up sheer. Twelve children of his, too, there are in the halls, six daughters and six sturdy sons, and he gave his daughters to his sons to wife. These, then, feast continually by their dear father and good mother, and before them lies boundless good cheer. And the house, filled with the savour of feasting, resounds all about even in the outer court by day, and by night again they sleep beside their chaste wives on blankets and on corded bedsteads.[13]

Aeolus entertained Odysseus and his men for a month, questioning Odysseus about all that had happened to him.[14] When Odysseus was ready to set sail again for home, Aeolus gave him a bag made of oxhide in which he had bound "the blustering winds", all except for the west wind, which Aeolus sent forth to bear Odysseus and his men safely home.[15] But when they came within sight of Ithaca their home, Odysseus was overcome with sleep, and his men, thinking that the bag held gifts of gold and silver that Odysseus intended to keep for himself, opened the bag letting loose all the unruly winds which drove their ship all the way back to Aeolus' floating island.[16] And when Odysseus asked again for help, Aeolus replied:

Begone from our island with speed, thou vilest of all that live. In no wise may I help or send upon his way that man who is hated of the blessed gods. Begone, for thou comest hither as one hated of the immortals.[17]

The same story is also recounted by Hyginus, Ovid, and Apollodorus.[18]

Aeolia

In the Odyssey, Aelolus' kingdom of Aeolia was purely mythical, a floating island surrounded by "a wall of unbreakable bronze". Later writers came to associate Aeolia with one of the Aeolian Islands, north of Sicily.[19]

Confused with Aeolus son of Hellen

This Aeolus was sometimes confused (or identified) with Aeolus the son of Hellen and eponym of the Aeolians.[20] The confusion perhaps first occurs in Euripides' Aeolus, where, although clearly based on the Odyssey's Aeolus, Euripides' Aeolus is the father of a daughter Canace, like Aeolus the son of Hellen, and if the two are not identified, then they seem, at least, to be related.[21] Hyginus, describes the Aeolus encountered by Odysseus as "Aeolus, son of Hellen".[22] While Ovid, has the ruler of the winds, like Aeolus the son of Hellen, the father of a daughter Alcyone, as well as the tragic lovers Canace and Macareus, and calls Alcyone "Hippotades", ie. a descendant of Hippotes.[23]

Diodorus Siculus' account

The rationalizing Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, explains how Aeolus came to be considered the ruler of the winds. According to Diodorus, Aeolus was said to be:

pious and just and kindly as well in his treatment of strangers; furthermore, he introduced sea-farers to the use of sails and had learned, by long observation of what the fire foretold, to predict with accuracy the local winds, this being the reason why the myth has referred to him as the "keeper of the winds"; and it was because of his very great piety that he was called a friend of the Gods.[24]

Diodorus Siculus—perhaps in order to resolve a confusion between this Aeolus and the Aeolus who was the son of Hellen—also made Aeolus's father Hippotes the son of a Mimas, who was the son of Aeolus the son of Hellen.[25] And while Homer does not name Aeolus' mother, wife, or children, Diodorus supplies names for all but his daughters. According to Diodorus, Aeolus' mother was Melanippe, his wife was Cyanê, and his six sons were Astyochus, Xuthus, Androcles, Pheraemon, Jocastus, and Agathyrnus.[26]

Gallery

Aeolus and Odysseus

Odysseus in the Cave of the Winds by Stradanus (possibly 1590-1599)

Odysseus in the Cave of the Winds by Stradanus (possibly 1590-1599) Aeolus Giving the Winds to Odysseus by Isaac Moillon

Aeolus Giving the Winds to Odysseus by Isaac Moillon

Aeolus and Juno

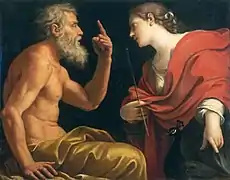

Aeolus and Juno by Lucio Massari

Aeolus and Juno by Lucio Massari_(Aeneid_I)%252C_1718.jpg.webp) Air (Juno orders Aeolus to release the winds) (Aeneid I) by Charles Dupuis (1718)

Air (Juno orders Aeolus to release the winds) (Aeneid I) by Charles Dupuis (1718) Juno en Aeolus by Cornelis Bos (1546)

Juno en Aeolus by Cornelis Bos (1546) Giunone ordina a Eolo di liberare i Venti (particolare), affresco nel Palazzo Sanvitale di Parma. (circa 1790)

Giunone ordina a Eolo di liberare i Venti (particolare), affresco nel Palazzo Sanvitale di Parma. (circa 1790)%252C_1800.jpg.webp) Air (Juno orders Aeolus to release the winds) by Manuel de Samaniego (circa 1800)

Air (Juno orders Aeolus to release the winds) by Manuel de Samaniego (circa 1800) Juno and King Aeolus at the Cave of winds by Antonio Randa (Italy, 1577-1650)

Juno and King Aeolus at the Cave of winds by Antonio Randa (Italy, 1577-1650)

Other

Aeolus

Aeolus Allegory of Winter by Jerzy Siemiginowski-Eleuter (1683)

Allegory of Winter by Jerzy Siemiginowski-Eleuter (1683) Book frontispiece of the sailing handbook "The light of navigation". (On the left side, Neptune, the god of water and the sea, on the right Aeolus, the ruler of the winds)

Book frontispiece of the sailing handbook "The light of navigation". (On the left side, Neptune, the god of water and the sea, on the right Aeolus, the ruler of the winds)

See also

Notes

- According to Kerényi, p. 206, the name means both "the mobile" and "the many coloured", while Rose, s.v. Aeolus (1) associates the name, "perhaps by derivation", with "the changeable". Chaucer's spelling of the name was "Eolus", the Middle English and Old French development of the Latin Aeolus, see de Weever, s.v. Eolus.

- Hard, pp. 493–494; Tripp, s.vv. Aeolus 1, 2; Rose, s.v. Aeolus (1); Grimal s.v. Aeolus; Parada s.v. Aeolus 2; Smith, s.v. Aeolus.

- Gantz, p. 169; Homer, Odyssey 10.1–12.

- Gantz, p. 169; Aeolus test. ii (Collard and Cropp, pp. 16, 17).

- Tzetzes, pp. 146, 147.

- Homer, Odyssey 10.21–22; Parada, s.v. Aeolus 2; Tripp, s.v. Aeolus 2; H. J. Rose, s.v. Aeolus (1). Compare with Apollodorus, E.7.10; Hyginus, Fabulae 125; Ovid, Metamorphoses 14.223–224.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 4.757–769, 4.757–769, 4.818–822.

- Virgil, Aeneid 1.50–58.

- Virgil, Aeneid 1.65–75.

- Virgil, Aeneid 1.81–101.

- Virgil, Aeneid 1.137–141.

- Virgil, Aeneid 1.124–156.

- Homer, Odyssey 10.1–12.

- Homer, Odyssey 10.13–16.

- Homer, Odyssey 10.17–22.

- Homer, Odyssey 10.23–55.

- Homer, Odyssey 10.67–75.

- Hyginus, Fabulae 125; Ovid, Metamorphoses 14.223–232; Apollodorus E.7.10–11.

- Hard, p. 494; Tripp, s.v. Aeolus 2.

- Hard 2004, p. 409; Gantz, pp. 167, 169; Grimal s.v. Aeolus; Tripp, s.vv. Aeolus 1, 2; Parada, s.v. Aeolus 1;

- Gantz, p. 169; Euripides fr. 14 (Collard and Cropp, pp. 16, 17) [= Strabo 8.3.32]; Euripides fr. 14 (Nauck, p. 366) (not in Collard and Cropp). For Canace the daughter of Aeolus son of Hellen, see Apollodorus, 1.7.3. For a discussion of the play along with the surviving testimonies and fragments see Collar and Cropp, pp. 31.

- Hyginus, Fabulae 125.

- Alcyone daughter of Aeolus: Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.415–416, 444–445, 457–458; Alycone called "Hippotades": Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.431; Alcyone's father Aeolus as ruler of the winds: Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.745–748; Canace and Macareus' father Aeolus as ruler of the winds: Ovid, Epistles 11.13–15. For Alcyone as daughter of Aeolus son of Hellen, see Apollodorus, 1.7.3; Hesiod fr. 10.31–34, 96 Most (Most, pp. 52, 53, 58, 59) [= fr. 10a.31–34, 96 MW = Turner papyrus fr. 1-4 col. I-III = Oxyrhynchus papyrus 2483 fr. 1 col. II].

- Diodorus Siculus, 5.7.7.

- Fowler, p. 188; Diodorus Siculus, 4.67.3.

- Diodorus Siculus, 4.67.3 (Melanippe), 5.7.6–7 (Cyanê), 5.8.1 (sons).

References

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. ISBN 0-674-99135-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Apollonius Rhodius: the Argonautica, translated by Robert Cooper Seaton, W. Heinemann, 1912. Internet Archive.

- Collard, Christopher and Martin Cropp, Euripides Fragments: Aegeus–Meleanger, Loeb Classical Library No. 504, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-674-99625-0. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, Volume III: Books 4.59-8, translated by C. H. Oldfather, Loeb Classical Library No. 340. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1939. ISBN 978-0-674-99375-4. Online version at Harvard University Press. Online version by Bill Thayer.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Grimal, Pierre, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 978-0-631-20102-1. Internet Archive.

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360. Google Books.

- Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Fabulae, in The Myths of Hyginus, edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960. Online version at ToposText.

- Kerényi, Karl, The Gods of the Greeks, Thames and Hudson, London, 1951. Internet Archive.

- Nauck, Johann August, Tragicorum graecorum fragmenta, Leipzig, Teubner, 1889. Internet Archive.

- Parthenius, Love Romances translated by Sir Stephen Gaselee (1882-1943), S. Loeb Classical Library Volume 69. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. 1916. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Ovid, The Epistles of Ovid, translated into English prose, as near the original as the different idioms of the Latin and English languages will allow; with the Latin text and order of construction on the same page; and critical, historical, geographical, and classical notes in English, from the very best commentators both ancient and modern; beside a very great number of notes entirely new; London. J. Nunn, Great-Queen-Street; R. Priestly, 143, High-Holborn; R. Lea, Greek-Street, Soho; and J. Rodwell, New-Bond-Street, 1813. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Brookes More, Boston, Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Parada, Carlos, Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology, Jonsered, Paul Åströms Förlag, 1993. ISBN 978-91-7081-062-6.

- Rose, H. J., s.v. Aeolus in the Oxford Classical Dictionary, second edition, Hammond, N.G.L. and Howard Hayes Scullard (editors), Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-869117-3.

- Virgil, Aeneid, Theodore C. Williams. trans. Boston. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1910. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Smith, William, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Strabo, Geography, translated by Horace Leonard Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. (1924). LacusCurtis, Online version at the Perseus Digital Library, Books 6–14.

- Tripp, Edward, Crowell's Handbook of Classical Mythology, Thomas Y. Crowell Co; First edition (June 1970). ISBN 069022608X.

- Tzetzes, John, Allegories of the Odyssey, translated by Adam J. Goldwyn, and Dimitra Kokkini, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 2019. ISBN 978-0-674-23837-4.

- Virgil, Aeneid, Theodore C. Williams. trans. Boston. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1910. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.