African American genealogy

African American genealogy is a field of genealogy pertaining specifically to the African American population of the United States. African American genealogists who document the families, family histories, and lineages of African Americans are faced with unique challenges owing to the slave practices of the Antebellum South and North.[1] These challenges rise from a range of events, including name changes following the American Civil War, the act of separating families for sale as slaves, lack of issued birth or death records for slaves, etc.[1]

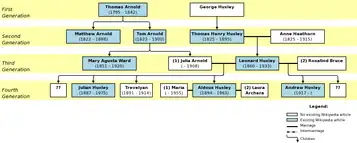

The development of a genogram – a structured version of a pedigree chart or family tree – serves as an integral part of identity development, specifically in African American populations.[2] In the twenty-first century, the internet has made the resources uniquely necessary to African American genealogy available to the public and the individual's personal ability to research, create, and maintain their own family tree has dramatically increased.

Recently, African American genealogy has made great strides forward, thanks to genealogical DNA testing, but some researchers warn of potential drawbacks.[3] DNA testing can help African Americans trace their ancestry to general regions in Africa.[4]

Family trees

Genealogy (from Greek: genea "generation, descent" and -logia "the study of")[5] is the study of and enumeration of families, family histories, and lineages. Genealogists use a number of resources – including, but not limited to, census records, death certificates, family trees, and oral histories – to document ancestral relationships and lines. Companies such as FamilySearch, Ancestry.com, and MyHeritage among others have encouraged people to become personal family genealogists and record and trace their own family histories.

The most common way personal family genealogists record their family histories is with family trees, also known as a pedigree chart or a genogram (a structured, formal family tree). A family tree is a physical representation of an individual's ancestors listed in a way that often resembles a tree. Family trees can range from a simplistic listing of parents, grandparents, great-grandparents etc. or a more complex listing of siblings, parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, and other relatives. Family trees can be highly stylized or rendered plainly. Family trees provide a clear visual representation of the members in one's family by displaying how everyone is related; they also include information regarding where and when individuals were born.

Challenges

African American genealogy can be challenging; tracking lost ancestors requires creativity and extensive research.

Lack of records

Slavery, racial prejudice, and Jim Crow laws mean that many records are inaccessible, unavailable, or incomplete. The 1870 federal census was the first to record many former slaves by name. This makes finding family members before then very difficult.[6] Because scant documentation of enslaved African Americans and their families exists, people must usually use slaveholders' or enslavers' records to find their ancestors before emancipation. Slaveholders’ records can provide hints or other clues about African Americans’ ancestry or their enslaved ancestors’ movements and life.[7] Relevant records include slaveholders' journals, history, paper trail, probate records, wills, and property deeds. Probate, account, and deed records will all be in the slaveholder's name.[8] Usually these records will include the number of slaves held, their names, and sometimes even age, sex, and birth.

Transferring property ownership

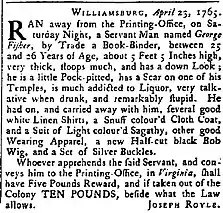

Slaves would often be bought and sold, moving from one person to another, as well as one plantation to the next. Some slaves ran away and then were caught and sold again. This sometimes constant movement causes challenges in tracking the location and residency of the ancestor. A large portion of slaveowners inherited their slaves from other family members. In these cases, looking at estate records, inventory documents, wills, and slave schedules is the most helpful.[9] When slaves were sold and bought by various people, a variety of records were kept. This can include property deeds, newspapers, probate records, and bills of sale.[10] Property deeds will often include information about when one person is transferring the ownership of their slave to the new buyer.

Name changes

Discovering a surname for a slave either during slavery or after slavery poses a great challenge because they were so often changed. After the passing of the Emancipation Proclamation, many former slaves adopted new names of their own choosing, or adopted the names and surnames of their previous owners.[11] Many slaves changed their last name to that of "Freedman" to represent their new standing in society. They did this to either adopt a surname for the very first time, or they wanted to replace a surname that was given to them by a former master.[12] There are many cases where a family once enslaved has passed down a name through several generations, and others chose a name that completely separated themselves from slavery and their former owners. Many newly freed slaves would choose the name of a popular person whom they admired, or considered influential and important. Some examples include changing their name out of admiration for a black or white abolitionist, or even to the surname of a U.S. president. Other freed slaves changed their names for reasons such as occupation, skills that they held, or a place where they had lived.[13] Some names were taken for reasons that will only ever be known by the former slaves themselves.[14] In other cases, they had their names assigned to them by record takers.[13]

Most of the records searched will have originated from the slave owner; these records were written for the benefit of the owners, not the slaves themselves. Enslavers rarely had knowledge of their slaves' chosen names; instead, records reflect the names enslavers used to differentiate slaves from one another. Because of these challenges, scrupulous research is necessary to learn ancestors’ names and the significance of those names.[15]

Resources

Types of records

Before the Emancipation:

| Record Type | Description |

|---|---|

| 1860 U.S. Census | Can identify names of slaveholders. |

| 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedules | A separate census used to identify slaves as property. It includes the names of slave owners along with details about the slaves they own. You can identify which plantations and families had slaves. |

| Manifests | Documents that detailed the cargo coming and going from ports. |

| Plantation Records | Includes details of slaves who lived there. |

| Property Deed | Can detail the possession of slaves and the transaction or transfer from one person to the next through deeds and Slave Trade registers. |

| Probate Records | Can include wills that show the transfer of slaves to family members, documents showing slaves counting as tax, and can even include public auction records. |

| Newspapers | Includes ads for the selling of slaves, ads calling for their imprisonment or apprehension, or ads to notify the slave owner of their apprehension. |

| Bill of Sale | Documents sometimes the name, sex, age, price sold, and other details of a slave who had been sold. |

| Estate Records | Generally lists the inventory of the estate, and typically listed enslaved individuals by name, included their age, and sometimes listed the family they belonged to. |

| Church Records | Lists members which can provide helpful hints to the identifying of slaves especially before the Civil War. |

| Military Records | Lists most if not all the vital information for black soldiers who served in the American Civil War and others. |

After the Emancipation:

| Record Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Emancipation Documents | Can include both manumissions and evidences or affidavits of freedom[16] |

| Bible Records | Would often list the name and dates of births, deaths, and marriages kept in old bibles. |

| Death Certificate | Wasn't required by law until the 20th century, but can help identify names of parents who lived before the Civil War. |

| Newspapers | Can contain obituaries, ads of freed blacks searching for their family etc. |

For more a further list of records and more detailed descriptions, click here

For steps on using these records, click here

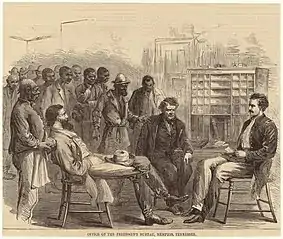

Freedmen's Bureau (1865–1872)

During Reconstruction, the United States Congress enacted the Freedmen's Bureau (also known as the Bureau of Refugees or Freedmen and Abandoned Lands) in 1865.[17] The Freedmen's Bureau could be considered one of the first federal welfare programs. It supervised relief efforts to help millions of African Americans transition from slavery to freedom and citizenship; moreover, the Bureau also supported impoverished whites with aid and provided general assistance in the postwar Southern states.[18] These programs included black colleges, hospitals, family-reunification programs, the reassignment of Confederate-owned land, the distribution of food and clothing, and the creation of legal records that contain the names of hundreds of formerly enslaved people and sometimes the name of their white owners.[19] For the years 1865 to 1872, the Freedmen’s Bureau is a priceless resource for African American genealogists searching for information about their ancestry, thanks to records such as legal marriage certificates, school records, census lists, medical records, and court records (to see a full list, click here).[20]

Records from the Freedmen's Bureau can provide a wealth of information about ancestors. These records can contain:

- The name of the individual

- Date the record was taken

- Residence

- Age

- Gender

- Birthdate

- Birthplace

- Death date and place

- Marriage date and place

- Names of family members

Although most records are in reference to recently freed slaves, anyone with ancestors living in the American South during this period can benefit.[21] Records may include other information, such as the name of a freed slave's former owner, former employers, and the names of record keepers or those who interacted with the Freedmen's Bureau.

List of databases for finding African American ancestors

This list does not satisfy particular standards for completeness; nevertheless, they can guide African Americans in their search for finding their ancestors.

| Database | Description |

|---|---|

| The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database | Analyzes various slave trades and view interactive maps, timelines, and animations to see the dispersal in action. |

| Large Slaveholders of 1860 | Can discover whether or not your ancestor was a slaveholder, and those of African-American descent can find their ancestor using the name of the slaveholder in order to find more information on their name, sex, color, and age. |

| Unknown No Longer | Provides users with access to an expanded collection of resources for researching African American history in Virginia. |

| Texas Runaway Slave Project | For about 2,500 slaves in Texas, it contains runaway slave advertisements, articles, and notices from newspapers published in Texas, as well as materials from court records, manuscript collections, and books. |

| Freedom on the Move | Collection of newspaper ads in the America colonies that include posted "runaway ads" by enslavers, as well as jailers’ descriptions of people they have apprehended. |

| Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery | Collection of thousands of "Information Wanted Ads" taken out by former slaves to look for your ancestors. |

| Lost Friends | Collection of ads written by formerly enslaved people in search of lost family and friends. |

- See also

DNA

Genealogical DNA testing has provided great strides forward in the tracing of African American genealogy.[3] Companies such as 23andMe, Ancestry.com, and MyHeritage all offer DNA test kits that allow people to trace their heritage back to approximate geographic locations.[4] For African Americans in the United States, who are often unsure of exactly where their ancestors were taken from as slaves, these results can be emotionally liberating.[3]

Most companies use one of three types of DNA testing : (1) Y-chromosome testing, (2) Mitochondrial DNA testing, or (3) autosomal DNA testing.[22] Y-chromosome testing traces ancestry through the paternal line.[22] Mitochondrial DNA testing traces ancestry through the maternal line.[22] Autosomal DNA testing traces ancestry through both lines.[22]

One often cited limitation of genealogical DNA testing are the shifting boundaries created by increased testing.[23] In large part because of the continued development of genealogical DNA testing, the current accuracy of these tests is not 100%.[23] As more DNA data points are gathered, the tests become more accurate.[23] It is not unheard of for this increase in accuracy to change the geographical test results of an individual.[23] The geographical boundaries between countries of modern day African also present a limitation.[4] These boundaries are not natural boundaries, but instead geo-political boundaries created by colonizing Europeans.[4] Additionally, historical migration can lead to discrepancies between familial expectation and reality.[22] One example is that ancestors who migrated to the Caribbean from Sub-Saharan Africa will not appear as Caribbean, but as Sub-Saharan African.

There is also a medico-ethical criticism often raised against using DNA testing to assist with building genograms specifically to help with identity development.[3] While it is acknowledged that DNA testing can provide African Americans with a crucial aspect of their past that has been stolen, the sole use of DNA testing to aid in identity development discounts the role culture plays in identity development.[3] African Americans are encouraged to use their DNA results hand in hand with childhood experiences to recognize their identity within the boundaries of both.[3] This leads to more complete identity development.

References

- "African American family research on Ancestry" (PDF).

- Mitchell, Michelle D.; Shillingford, M. Ann (November 20, 2016). "A Journey to the Past: Promoting Identity Development of African Americans Through Ancestral Awareness". The Family Journal. 25 (1): 63–69. doi:10.1177/1066480716679656. S2CID 152278122.

- Dula, Annette; Royal, Charmaine; Secundy, Marian Gray; Miles, Steven (2003). "The Ethical and Social Implications of Exploring African American Genealogies". Developing World Bioethics. 3 (2): 133–141. doi:10.1046/j.1471-8731.2003.00069.x. ISSN 1471-8847. PMID 14768645.

- Rotimi, Charles N. (2003). "Genetic Ancestry Tracing and the African Identity: A Double-Edged Sword?". Developing World Bioethics. 3 (2): 151–158. doi:10.1046/j.1471-8731.2003.00071.x. ISSN 1471-8847. PMID 14768647.

- "genealogy (n.)".

- Siekman, Meaghan E. H. n.d. African American Genealogy. New England Historic Genealogical Society. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- Grimm, Jessica. 2018. African American Genealogy: A Guide to Finding Your Ancestors Online. February 26. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- Hyland, David. 2020. Facing Challenges, Genealogist Offers Ideas To Trace African American Family Histories. February 28. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- MySlaveAncestors.com. 2011. Estate Records. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- n.d. American Slavery Documents. Duke University Libraries. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- 2020. Facing History and Facing Ourselves. Facing History and Facing Ourselves. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- Shell, Robert. n.d. Cape Slave Naming Patterns. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- Jr., Henry Louis Gates, and Meaghan E.H. Siekman. 2017. Tracing Your Roots: Were Slaves' Surnames Like Brands? June 17. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- Shell, Robert. n.d. Cape Slave Naming Patterns. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- Paterson, David (2001). "A Perspective on Indexing Slaves' Names". The American Archivist. 64 (1): 132–142. doi:10.17723/aarc.64.1.th18g8t6282h4283.

- n.d. Illinois Servitude and Emancipation Records (1722–1863). Illinois State Archives. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- Editors, History.com. 2010. Freedmen's Bureau. A&E Television Networks.

- 2016. African American Records: Freedmen's Bureau. National Archives. September 19. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- Hurst, Ryan. 2009. Freedmen's Bureau (1865-1872). February 16. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- n.d. The Freedman's Bureau Records. National Museum of African American History and Culture. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- "genealogy, n.". OED Online. September 2020. Oxford University Press.n.d. African American Freedmen's Bureau Records. Family Search.

- "Types of DNA Testing | DNA Testing | AncestryDNA® Learning Hub". www.ancestry.com. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- Bamshad, Michael J.; Wooding, Stephen; Watkins, W. Scott; Ostler, Christopher T.; Batzer, Mark A.; Jorde, Lynn B. (March 2003). "Human Population Genetic Structure and Inference of Group Membership". American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (3): 578–589. doi:10.1086/368061. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1180234. PMID 12557124.