Afrikan Spir

Afrikan Aleksandrovich Spir[lower-alpha 1] (1837–1890) was a Russian neo-Kantian philosopher of German-Greek descent who wrote primarily in German, but also French.[2][3][4]

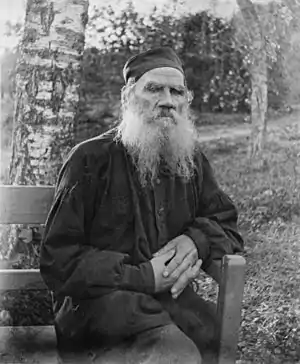

Afrikan Spir | |

|---|---|

Photograph of Afrikan Spir taken by Fred Boissonnas c.1887 (Fonds Fred Boissonnas, Bibliothèque de Genève) | |

| Born | 10 November 1837[1] |

| Died | 26 March 1890 (aged 52) |

| Notable work | Thought and Reality, (Denken und wirklichkeit), 1873 |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neo-Kantianism |

Main interests | Logic, epistemology, ontology, religion, morality |

His book Denken und Wirklichkeit (Thought and Reality) had a significant influence on several eminent philosophers, scholars and writers such as Hans Vaihinger, Friedrich Nietzsche, William James, Leo Tolstoy and Rudolf Steiner.[lower-alpha 2]

Biography

Early life and family

Afrikan Spir was born on 10 November 1837 in his father's estates of Spirovska, near the city of Elisavetgrad (Elizabethgrad, Kherson Governorate, Russian Empire now Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine).[1][lower-alpha 3]

His father, Alexander Alexandrovich Spir, of German descent, was a Russian surgeon—Chief Physician of the military Hospital of Odessa specifically—and former professor of mathematics in Moscow. In 1812, he received the Order of St. Vladimir, was knighted, and became councillor and member of Kherson's Governorate hereditary nobility.[lower-alpha 4] His mother, Helena Constantinovna Spir, daughter of the major Poulevich, was on her mother's side the granddaughter of the Greek painter Logino, who arrived in Russia under the reign of Catherine the Great.[5][lower-alpha 5]

Alexander and Helena had four children—three boys and one girl— Aristarque, Kharitine, Alexandre and African.[6] The names were chosen, on the whim (un caprice) of their father, from an old synaxis of the Orthodox calendar, which is the source of the curious name "Afrikan" (a very uncommon name of a minor orthodox saint, the father of Šimon).[7] Spir disliked his Christian name, simply signing his letters and books "A. Spir". His modesty impelled him not to use either the German "von" or the French "de"—denoting his noble status—before his family name.[lower-alpha 6]

Education

He described his education as follows: "I spent my childhood in the countryside and later I studied for a while in Odessa, first in a Private boarding-school and after in a Gymnasium, more or less equivalent, if I do not mistake, to a French high-school".[8]

During this period he developed an interest in philosophy and read (in the French translation of Tissot) Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, which gave him the basis of his speculative thought. He later followed the readings of Descartes, David Hume, and Stuart Mill.[lower-alpha 7]

Later he went to Leipzig where he attended the lectures of Moritz Wilhelm Drobisch (1802–1896), a Herbartian philosopher and one of the forerunners of the neo-Kantian revival of the 1860s. He was there at the same time that Nietzsche was a student, although it does not appear that they met.

Military service

After gymnasium, Spir entered the Midshipmen's School in Nikolayev (now Mykolaiv), not far from the Black Sea.[8] In 1855, at the age of 18, he participated as Sub-lieutenant of the Russian navy in the Crimean War, during which he was twice decorated (Order of St. Andrew and Order of St. George). Spir defended the same bastion (N. 4 at Malakoff) as Leo Tolstoy during the siege of Sevastopol.

Later life, marriage and Swiss citizenship

After his father's death in 1852, he inherited his father's estates (his last remaining brother, the poet Aristarch, having died in 1841) whereupon he emancipated his serfs and gave them land, goods and money, presaging the reform of 1861.

In 1862, he left Elizabethgrad for a tour in Germany, where he spent two years "to know better the mind's matter".[8] His sister Charitis died soon after his return to Russia in 1864. After the death of his mother, in 1867, he sold his estates at a ridiculously low price, distributed almost all of his possessions and left Russia permanently.[5]

In 1869, he moved to Tübingen and to Stuttgart in 1871. Here, at the orthodox Church of the Court,[lower-alpha 8] he married on 30 January 1872, Elisabeth (Elise) Gatternich.[9][lower-alpha 9] The couple had a daughter, Hélène.[lower-alpha 10]

In 1884, Spir asked the Russian Emperor for an allowance to forsake Russian citizenship and to obtain Swiss citizenship. In the same year, he received the imperial authorization and applied for a certificate of registry at Belmont-sur-Lausanne, where he lived with his family. In 1886, to enjoy the facilities of a bigger library (the "Société de Lecture", a private reading society),[lower-alpha 11] he moved to Geneva.[lower-alpha 12] On 17 September 1889, he received authorization for his wife, his daughter, and himself to become Swiss citizens from the Swiss Federal Government.[10]

Death

In 1878, having suffered from pneumonia, in order to treat the consequences of his illness, a chronic cough, Spir moved to Lausanne, Switzerland, where he spent five years.

He died of influenza on 26 March 1890 in Geneva, at 6 rue Petitot.[lower-alpha 13] He was buried in the Saint-Georges cemetery. He was survived by his wife Elisabeth and his daughter, Hélène.[5]

Writings

In Leipzig, Spir befriended the publisher and fellow Freemason Joseph Gabriel Findel, who published most of Spir's works. His most important book, Denken und Wirklichkeit: Versuch einer Erneuerung der kritischen Philosophie (Thought and Reality: Attempt at a Renewal of Critical Philosophy) was published in 1873. A second edition, which was the one owned by Nietzsche, was published in 1877. In an attempt to reach a broader readership, Spir wrote directly in French his Esquisses de philosophie critique (Outlines of critical philosophy), published for the first time in 1877.[lower-alpha 14] A new edition was published forty years after his death, in 1930, with an introduction by the French philosopher and professor at the Sorbonne Léon Brunschvicg.

Manuscripts, personal papers, photographs, books by or on African Spir were donated in March 1940 by his daughter Hélène Claparède-Spir (who was married to the Swiss neurologist Édouard Claparède) to the Library of Geneva (Bibliothèque de Genève, formerly Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire de Genève), where they compose the "Fonds African Spir" and can be consulted.[11][12]

Other papers concerning Spir, his daughter Hélène Claparède-Spir and her family can be consulted at Harvard University Library.

Autobiography

Spir provided a biographical sketch ("esquisse biographique") of himself that he added to some of his letters of correspondence, after 1882:

Je m'appelle African Spir (ce prénom étrange et insolite, que je dois à un caprice de mon père, me gêne assez quelquefois). Je suis né le 15 novembre 1837, dans la Russie du Sud, et j'ai été élevé dans la religion gréco-russe, quoique mon père fût protestant. J'ai passé mon enfance à la campagne, et j'ai fait plus tard quelques études à Odessa, dans un gymnase qui correspond à peu près, si je ne me trompe, à un lycée francais. Je n'ai pas fait, d'études universitaires, mais je suis entré à l'ecole des aspirants de marine, à Nicolayew, près de la mer Noire. Au sortir de cette école, en 1856, J'ai quitté le service naval et me suis retiré dans une campagne qui m'appartenait. En 1862, je partis pour l'Allemagne et y passai deux ans, pour être plus au courant des choses de l'esprit. En 1867, j'ai quitté la Russe définitivement, et j'ai vécu en Allemagne, d'abord à Leipzig, puis à Stuggart, où je me mariai. De 1882 jusqu'a présent, j'ai demeuré à Lausanne. Je n'ai jamais eu d'autre occupation que la lecture et la méditation solitaire, étant de plus, d'une santé faible et sujet, depuis sept ans, à une toux chronique.

My name is African Spir (this strange and unusual name, which I owe to a whim of my father, quite bothers me sometimes). I was born on November 15, 1837, in South Russia, and I was raised in the Greco-Russian religion, although my father was a Protestant. I spent my childhood in the countryside, and later I studied in Odessa, in a gymnasium that corresponds more or less, if I am not mistaken, to a French high school. I didn't go to university, but I entered the Midshipmen's School in Nicolayew, near the Black Sea. On leaving this school, in 1856, I left the naval service and retired to a countryside that belonged to me. In 1862 I left for Germany and spent two years there, to be more aware of spiritual matters. In 1867, I left Russia permanently, and I lived in Germany, first in Leipzig, then in Stuggart, where I married. From 1882 until now, I have lived in Lausanne. I have never had any other occupation than reading and solitary meditation, being moreover, of poor health and subject, for seven years, to a chronic cough.

— "Textes Ajoutés par Spir A Certaines de Ses Lettres", Lettres Inédites de African Spir au professeur Penjon. Éditions du Griffon Neuchâtel (Introduction de Emile Bréhier), pp.207-208 (1948).

Honours

Order of St. Andrew

Order of St. Andrew Order of St. George (fourth class)

Order of St. George (fourth class)

Philosophy

Epistemology

Due to his personal readings and his attending of Drobisch's lectures, Spir must be considered as a neo-Kantian philosopher. Spir referred to his philosophy as "critical philosophy". He sought to establish philosophy as the science of first principles, he held that the task of philosophy was to investigate immediate knowledge, show the delusion of empiricism, and present the true nature of things by strict statements of facts and logically controlled inference. This method led Spir to proclaim the principle of identity (or law of identity, A ≡ A) as the fundamental law of knowledge, which is opposed to the changing appearance of empirical reality.[13]

Ontology

For Spir the principle of identity is not only the fundamental law of knowledge, it is also an ontological principle, expression of the unconditioned essence of reality (Realität=Identität mit sich), which is opposed to the empirical reality (Wirklichkeit), which in turn is evolution (Geschehen).[14] The principle of identity displays the essence of reality: only that which is identical to itself is real, the empirical world is ever-changing, therefore it is not real. Thus the empirical world has an illusory character, because phenomena are ever-changing, and empirical reality is unknowable.

Religion and morality

Religion, morality and philosophy, have for Spir the same theoretical foundation: the principle of identity, which is the characteristic of the supreme being, of the absolute, of God. God is not the creator deity of the universe and mankind, but man's true nature and the norm of all things, in general. The moral and religious conscience live in the consciousness of the contrast between this norm (Realität) and empirical reality (Wirklichkeit). "There is a radical dualism between the empirical nature of man and his moral nature"[15] and the awareness of this dualism is the sole true foundation of moral judgment.[16]

Social justice

Socially, Spir was not favourable to inherited wealth's accumulation in private hands and demanded just distribution of material goods, but disapproved of collectivism.[17] He set the example, redistributing his personal inherited land properties to his former serfs.[5]

Critical reception

Although he spent most of his life as a philosopher, Spir never held a university appointment and his writings remained relatively unknown and unrecognized throughout his life. Indeed, Spir complained of a wall or conspiracy of silence (das Totschweigen).[18] Yet, he had a significant influence on several eminent philosophers, scholars and writers such as Hans Vaihinger, Friedrich Nietzsche, William James, Leo Tolstoy and Rudolf Steiner. Vaihinger read Spir's Thought and Reality as soon as it was published (1873) and recalls that it made a "great impression".[lower-alpha 15] Nietzsche described him as "a distinguished logician" (eines ausgezeichneten logikers) and "the logician I value" (Der von mir geschätzte Logiker heißt: A. Spir).[19][20] James makes several references to Spir in his Principles of Psychology, for example when debating a certain Kantian issue he wrote, "On the whole, the best recent treatment of the question known to me is in one of A. Spir's works, his Denken und Wirklichkeit".[21]

In 1896 Leo Tolstoy read Thought and Reality and was also deeply impressed, as he mentioned in a letter to Hélène Claparède-Spir: "reading Thought and Reality has been a great joy for me. I do not know a philosopher so profound and at the same time so precise, I mean scientific, accepting only what is strictly necessary and clear for everybody. I am sure that his doctrine will be understood and appreciated as it deserves and that the destiny of his work will be similar to that of Schopenhauer, who became known and admired only after his death".[22][lower-alpha 16]

In his Journal (2 May 1896) Tolstoy wrote: "Still another important event the work [Thought and Reality] of African Spir. I just read through what I wrote in the beginning of this notebook. At bottom, it is nothing else than a short summary of all of Spir's philosophy which I not only had not read at that time, but about which I had not the slightest idea. This work clarified my ideas on the meaning of life remarkably, and in some ways strengthened them. The essence of his doctrine is that things do not exist, but only our impressions which appear to us in our conception as objects. Conception (Vorstellung) has the quality of believing in the existence of objects. This comes from the fact that the quality of thinking consists in attributing an objectivity to impressions, a substance, and a projecting of them into space". The next day (3 May 1896) he added, "I am reading Spir all the time, and the reading provokes a mass of thoughts".

The most important works on Spir's philosophy were published between 1900 and 1914 (Theodor Lessing, Andreas Zacharoff, Joseph Segond, Gabriel Huan, Piero Martinetti).

In a lecture given in 1917, Rudolf Steiner called Spir "extraordinarily fascinating" and an "original thinker", and someone possessed of a "subtlety" not found in his 19th century contemporaries. As a consequence, Spir was unfortunately not understood and "suffered all the distress that a thinker can experience from being entirely ignored; killed by silence as the saying goes".[23] After the First World War, the interpretation of Spir's thought by the Italian philosopher Martinetti gave it a second life for a short while, in the form of a "religious idealism".[24][25]

Before the Second World War, Hélène Claparède-Spir published some new editions of her father's books in French and had an extensive exchange of letters to promote her father's thought.[26] In 1937, for the centennial of Spir's birth, Martinetti published in Italy a monographic edition on Spir of the Rivista di Filosofia (Philosophical Review).[27]

After the Second World War, African Spir fell into oblivion. In 1990, for the centennial of Spir's death in Geneva, the Geneva Public Library organized an exhibition of African Spir's corpus[28] and published the analytical catalogue.[12] Many of Spir's books have not been entirely sold and are still available in their first or second edition (in German, French, Italian, English, or Spanish translations). Presumably, due to the increasing interest in the argument at the beginning of the twenty-first century, a reprint of the Italian translation by Odoardo Campa in 1911 of Spir's Moralität und Religion (1874) has been published in 2008.[29]

Works

- 1866. Die Wahrheit, Leipzig, J.G. Findel (under the pseudonym of "Prais", anagram of: A. Spir, 2nd ed. under the name of A. Spir 1867, Leipzig, Förster und Findel).

- 1868. Andeutung zu einem widerspruchlosen Denken, Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1869. Erörterung einer philosophischen Grundeinsicht, Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1869. Forschung nach der Gewissheit in der Erkenntniss der Wirklichkeit, Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1869. Kurze Darstellung der Grundzüge einer philosophischen Anschauungsweise, Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1869. Vorschlag an die Freunde einer vernünftigen Lebensführung, Leipzig, J.G. Findel (French translation by Hélène Claparède-Spir: Projet d'un coenobium laïque, Ed. of Coenobium, Lugano, 1907).

- 1870. Kleine Schriften, Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1873. Denken und Wirklichkeit: Versuch einer Erneuerung der kritischen Philosophie, 1st ed. Leipzig, J. G. Findel.

- 1874. Moralität und Religion, 1st ed. Leipzig, J.G. Findel. (Italian translation by Odoardo Campa: Religione, Lanciano, Carabba, 1911, reprint 2008).

- 1876. Empirie und Philosophie: vier Abhandlungen, Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1876. "Zu der Frage der ersten Principien", in: Philosophische Monatshefte, XII, p. 49–55.

- 1877. Denken und Wirklichkeit: Versuch einer Erneuerung der kritischen Philosophie, 2d ed. Leipzig, J. G. Findel.

(French translation from the 3rd ed. by A. Penjon: Pensée et réalité: essai d'une réforme de la philosophie critique, Lille, Au siège des Facultés – Paris, Alcan, 1896). - 1877. Sinn und Folgen der modernen Geistesströmung, 1st ed. Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1878. Moralität und religion, 2d ed. Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1878. Sinn und Folgen der modernen Geistesströmung, 2d ed. Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1879. Johann Gottlieb Fichte nach seinen Briefen, Leipzig, J. G. Findel.

- 1879. Recht und Unrecht: Eine Erörterung der Principien, Leipzig, J.G. Findel.(2nd ed., 1883, Italian translation by Cesare Goretti: La Giustizia, Milano, Lombarda, 1930; French translation: Principes de justice sociale, Genève: Éditions du Mon-Blanc (Hélène Claparède-Spir ed., Préf. de Georges Duhamel); English translation by Alexander Frederick Falconer: Right and Wrong, Edinburgh, Oliver and Boyd, 1954).

- 1879. Ueber Idealismus und Pessimismus, Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1879. "Ob eine vierte Dimension des Raums denkbar ist?", in: Philosophische Monatshefte, XV, p. 350–352.

- 1880. Vier Grundfragen, Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1883. Studien, Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1883. Über Religion: Ein Gespräch, 1st ed. Leipzig, J.G. Findel. (Italian translation by O. Campa, Ed. of Coenobium, Lugano, 1910.

- 1883–85. Gesammelte Schriften Leipzig:, J.G. Findel, (republished in 1896 by Paul Neff, Stuttgart).

- 1885. Philosophische Essays, Leipzig:, J.G. Findel, (republished in 1896 by Paul Neff, Stuttgart).

- 1887. Esquisses de philosophie critique, Paris, Ancienne librairie Germer-Baillière et Cie, F. Alcan éditeur. (Russian translation by N. A. Bracker, Moscow, 1901; Italian translation by O. Campa, with an introduction by P. Martinetti, Milan, 1913).

- 1890. Deux questions vitales: De la Connaissance du bien et du mal; De l'immortalité, Genève, Stapelmohr (published anonymously).

- 1895. "Wie gelangen wir zur Freiheit und Harmonie des Denkens", in: Archiv für systematische Philosophie, Bd. I, Heft 4, p. 457–473.

- 1897. Über Religion: Ein Gespräch, 2d ed. Leipzig, J.G. Findel.

- 1899. Nouvelles esquisses de philosophie critique (études posthumes), Paris, Librairie Félix Alcan, (Spanish translation by R. Urbano, Madrid, 1904).

- 1908–1909. Gesammelte Werke, Leipzig, J.A. Barth (Hélène Claparède-Spir ed.).

- 1930. Esquisses de philosophie critique, Paris, Libraire Félix Alcan (Nouvelle éd. avec une introduction par Léon Brunschvicg, Membre de l'Institut)

- 1930. Propos sur la guerre, Paris, Editions Truchy-Leroy (Hélène Claparède-Spir ed.).

- 1937. Paroles d'un sage, Paris-Genève, Je Sers-Labor (Choix de pensées d'African Spir avec une esquisse biografique, Hélène Claparède-Spir ed., 2d ed. Paris, Alcan, 1938).

- 1948. Lettres inédites de African Spir au professeur Penjon, Neuchâtel, Éditions du Griffon (Introd. d'Emile Bréhier).

Selected thoughts

To celebrate the centenary of his birth, a selection of Spir's thoughts, Paroles d'un sage ("words of a sage"), was collated and published by his daughter, Hélène Claparède-Spir in 1937.[30] Some of these thoughts were later reproduced in a collection of Spir's letters.[31] For an English translation of Spir's thoughts, see African Spir.

References

- Papiers de la famille Spir. Certificat de naissance d'African Spir, Ms. fr. 1406/2. Bibliothèque de Genève.

- Afrikan Spir. Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse.

- Spir, Afrikan Alexandrovich (1837–1890). Encyclopedia.com.

- Zeldin, Mary-Barbara (1950) History of Russian Philosophy. Spir, Afrikan Alexandrovich. Kropyvnytskyi Region Universal Research Library.

- Claparède, Hélène Spir (1920). Un précurseur, A. Spir. Avec une Préface par Georges Duhamel (in French). Payot & cie.

- Papiers de la famille Spir. Official documents attesting to the dates of birth of Alexandre Spir's children, Ms. l. e. 250/6, pièce 15. Bibliothèque de Genève.

- Lettres inédites de African Spir au professeur Penjon. Neuchâtel, Éditions du Griffon (Introd. d'Emile Bréhier), 1948, p.207.

- Fabrizio Frigerio (1990) Catalogue raisonné du fonds African Spir. Autobiographical notice, Personal Papers of African Spir, Ms. fr. 1409, 5, no.7. Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire de Genève.

- Papiers de la famille Spir. Certificat de mariage d'African Spir et Elisabeth Gatternicht, Ms. fr. 1406/10. Bibliothèque de Genève.

- Fabrizio Frigerio (1990) Catalogue raisonné du fonds African Spir. Authorization N. 347, Personal Papers of African Spir, p.6, no.25. Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire de Genève.

- Papiers de la famille Spir. Bibliothèque de Genève.

- Fabrizio Frigerio (1990) Catalogue raisonné du fonds African Spir. Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire de Genève.

- Forschung nach der Gewissheit in der Erkenntniss der Wirklichkeit, Leipzig, J.G. Findel, 1869 and Denken und Wirklichkeit: Versuch einer Erneuerung der kritischen Philosophie, Leipzig, J. G. Findel, 1873.

- Forschung nach der Gewissheit in der Erkenntniss der Wirklichkeit, p. 13.

- Hélène Claparède-Spir, Paroles d’un sage : choix de pensées d’African Spir, op. cit., p. 59.

- Moralität und Religion, Leipzig, J.G. Findel, 1874.

- Recht und Unrecht: Eine Erörterung der Principien, Leipzig, J.G. Findel, 1879.

- Lettres inédites de African Spir au professeur Penjon. Neuchâtel, Éditions du Griffon (Introd. d'Emile Bréhier), 1948, p.52.

- Nietzsche, F. (1908) Human, All Too Human. A Book for Free Spirits, Translated by Alexander Harvey. Part 1, §18. Charles H. Kerr & Company. Project Gutenberg eBook.

- Nietzsche, F. (1879) Letter to Ernst Schmeitzner, 22 November. Nietzsche Source, BVN-1879, 907.

- James, W. (1891) The Principles of Psychology. In Two Volumes, Vol. II. London: MacMillan and Co., p.662.

- Hélène Claparède-Spir (1944) Evocation: Tolstoi, Nietzsche, Rilke, Spir, Genève, Georg et Cie.

- Steiner, R. (1985) Lecture I Berlin, 31 July 1917. Forgotten Aspects of Cultural Life. In, The Karma of Materialism. Anthroposophic Press. pp.1–20.

- Piero Martinetti, Il pensiero di Africano Spir (African Spir's Thought), edited by Franco Alessio, Torino, Albert Meynier, 1990.

- Franco Alessio (1950) L'idealismo religioso di Piero Martinetti, Brescia, Morcelliana, (Alessio's dissertation at Pavia).

- Fabrizio Frigerio (1990) Catalogue raisonné du fonds African Spir. Letters to Hélène Claparède-Spir concerning her father African Spir, p.16, n. 30. , Ms. 1.e. 254. Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire de Genève.

- Rivista di filosofia, 1937, a. XXVIII, n. 3, Africano Spir nel primo centenario della nascita.

- Fabrizio Frigerio, "Un philosophe russe à Genève: African Spir (1837–1890)", in Musées de Genève, 1990, 307, p. 3-7.

- Africano Spir, Religione, Traduzione dal tedesco con prefazione e una bibliografia di Od. Campa, Lanciano, Carabba editore, 2008 (Ristampa anastatica della edizione originale).

- Spir, A. and Claparède-Spir, H. (1937) Paroles d'un sage, choix de pensées d'African Spir. Félix Alcan.

- Lettres inédites de African Spir au professeur Penjon, Neuchâtel, Éditions du Griffon (Introd. d'Emile Bréhier), 1948, pp.223-228.

Notes

- Russian: Африка́н Алекса́ндрович Спир; German: Afrikan (von) Spir; French: African (de) Spir; Italian: Africano Spir.

- For Nietzsche's annotations in his copy of African Spir's Thought and Reality, as well as Hélène's Claparède-Spir comments on these annotations in a letter in German to Hans Vaihinger (dated Geneva, March, 11th, 1930), cf. Fabrizio Frigerio (1990) p. 15, n. 29 c., Ms. l.e. 253.

- In the biography of Afrikan Spir written by his daughter Hélène as an introduction to Nouvelles Esquisses de Philosophie Critique, his date of birth is given as 15 November 1837 (Vie de A. Spir, p.IX).

- According to the Russian Law about the Nobility, people who were awarded with the St. Vladimir Order (each class) had had the rights of hereditary nobility until the Emperor's Decree of 1900 was issued. After this only three first classes of the Order gave such a right.

- In the biography of Afrikan Spir written by his daughter Hélène as an introduction to Nouvelles Esquisses de Philosophie Critique, his mother's name is given as Elena Arsenowna Poulevich (Vie de A. Spir, p.IX).

- Or to abridge it, if it was absolutely necessary to maintain it, like in his engagement-card: "A. v. Spir-Elise Gatternicht Verlobte Odessa December 1871 Stuttgart", cf.Ibid., p. 4, Personal papers of African Spir, Ms. fr. 1406, 2, no.7.

- "two philosophers, Stuart Mill and David Hume, that he appreciated very particularly, and who always stayed his preferred authors, "because, he said, of their clarity et of their perfect sincerity". Hélène Claparède-Spir, Paroles d'un sage : choix de pensées d'African Spir, (Words of a wise man: choice of Spir's words) Paris-Genève, Je Sers-Labor, 1937, p.24.

- Ibid.: "I was educated and baptized in the Greco-Russian faith, although my father was a Protestant."

- Elise Sophie Adelaïde Gatternicht, born on 4 June 1850 in Stuttgart, daughter of Johann Adam Gatternicht and Jeanne Catherine, born Heuss (Excerpt of Certificate of Birth, Stuttgart, 19 July 1883), Fabrizio Frigerio (1990) p. 4, Personal Papers of African Spir, Ms. fr. 1406, 5, nos. 8 and 9.

- Hélène-Catherine-Augusta Spir (Stuttgart, 14 February 1873 – Geneva, 12 November 1955), who will marry the Swiss neurologist and psychologist Edouard Claparède (Geneva, 24 March 1873 – Geneva, 29 September 1940) and became Hélène Claparède-Spir (or Elena Afrikanovna Klapared-Spir, in russian: Елона Африкановна Клапаред-Спир (Шпир).

- Due to his chronic cough, it was not possible for Spir to read books in a public library; as a member of the "Société de Lecture" it was possible for him to take at home the books that he wanted to read.

- Establishment's Setting n. 18529, delivered 19 June 1886, to Mr. African De Spir, without profession, born 10 November 1837, from Russia, married to Miss Eisabeth De Gatternicht, Fabrizio Frigerio (1990) p. 5, no. 24.

- Spir died at 9 PM, Fabrizio Frigerio, Catalogue raisonné du fonds African Spir (Analytical Catalogue of Afrikan Spir's Corpus) p. 6, n. 28. Death certificate of African Spir, 26 March 1890 (Vol. 1890, n. 139).

- "The author of the present Outlines who, without being himself a German, has published many books in German, will submit his philosophy to the scrutiny of the French Public.", Fabrizio Frigerio (1990) p. 9, no. 14, Ms. fr. 1410.

- "I was 21 years old when in 1873 was published this important book (Thought and Reality by A. Spir), which I started immediately to study diligently. The book produced immediately a great impression." 8 March 1930, in a memory on an article of the Nouvelles littéraires (Literary News) on Nietzsche and Spir.

- The original letter can be consulted at the Bibliothèque de Genève, cf. Fabrizio Frigerio (1990) p.17, n. 2. Manuscript letter (in French) to Hélène Claparède-Spir in Stuttgart, 1/13 May 1896.

Further reading

- Selected works on Spir

- Charles Baudouin, "Le philosophe African Spir (1837–1890). A l'occasion de son centenaire", in: Action et Pensée, 1938, juin, p. 65–75.

- Léon Brunschvicg, "La philosophie religieuse de Spir" in: Comptes rendus du II ème Congrès international de philosophie, Geneva, 1904, p. 329–334.

- Jean-Louis Claparède, "Spir signifie-t-il pour la philosophie un nouveau départ?", Travaux du IXe Congrès international de Philosophie, Congrès Descartes, Paris, Hermann, 1937, tome XI, p. 26.

- Hélène Claparède-Spir, Evocation. Tolstoï – Nietziche – Rilke – Spir. Georg et Cie. Libraires de l'Universitié, Genevé. 1944.

- Hélène Claparède-Spir, Un précurseur: A. Spir, Lausanne-Genève, Payot & Cie, 1920.

- Hélène Claparède-Spir, "Vie de A. Spir" in African Spir, Nouvelles esquisses de philosophie critique, Paris, Félix Alcan, 1899.

- Augusto Del Noce, Filosofi dell'esistenza e della libertà, Spir, Chestov, Lequier, Renouvier, Benda, Weil, Vidari, Faggi, Martinetti, Rensi, Juvalta, Mazzantini, Castelli, Capograsssi, a cura di Francesco Mercadante e Bernardino Casadei, Milano, Giuffrè, 1992.

- Fabrizio Frigerio, Catalogue raisonné du fonds African Spir, Genève, Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire de Genève, 1990.

- Fabrizio Frigerio, "Un philosophe russe à Genève: African Spir (1837–1890)", in: Musées de Genève, 1990, 307, p. 3–7.

- Fabrizio Frigerio, "Spir, Afrikan Alexandrowitsch", in: Schweizer Lexikon, Mengis & Ziehr Ed., Luzern, 1991–1993, t. VI, p. 31.

- Adolphe Ferrière, "African Spir", in: Bibliothèque universelle, 1911, vol. 63, p. 166–175.

- Alfred Haag, Der Substanzbegriff und eine erkentniss-theoretischen Grundlagen in der Philosophie des Afrikan Spir, 1837–1890. Historisch-kritischer Beitrag zu neueren Philosophie, Würzburg, 1923–224.

Haag's dissertation at Würzburg. - Gabriel Huan, Essai sur le dualisme de Spir, Paris, Librairie Félix Alcan, 1914.

Huan's dissertation at Paris. - Humanus, (pseud. of Ernst Eberhardt), African Spir: ein Philosoph der Neuzeit, Leipzig, J.G.Findel, 1892 (New ed. 2009).

- Theodor Lessing, African Spirs Erkenntnislehre, Gießen, Münchow, 1900.

Lessing's dissertation at Erlangen. (African Spirs Erkenntnislehre (1899), in: Kantstudien, Bd. 6, Berlin, 1901) - Piero Martinetti, "Africano Spir", in: Rassegna nazionale, 1913, fasc. 16 gennaio-11 febbraio.

- Piero Martinetti, La libertà, Milan, Lombarda, 1928, Spir: pp. 282–289 (new ed. Torino, Aragno 2004, Spir: p. 248–254).

- Piero Martinetti, Il pensiero di Africano Spir, Torino, Albert Meynier, 1990.

Published and with an introduction by Franco Alessio.

Review by Fabrizio Figerio in: Revue de Théologie et de Philosophie, Lausanne, 1993, 125, p. 400. - Auguste Penjon, "Spir et sa doctrine", Revue de métaphysique et de morale, 1893, p. 216–248.

- Rivista di filosofia, 1937, a. XXVIII, n. 3, Africano Spir nel primo centenario della nascita: *** "Africano Spir (1837–1890)"; E. Carando "La religione in Africano Spir", A. Del Noce " Osservazioni sul realismo e l'idealismo in A.Spir"; *** "Il dolore nel pesssimismo di A. Spir"; P. Martinetti "Il dualismo di A.Spir"; A. Poggi "Luci ed ombre nella morale di Africano Spir"; G. Solari "Diritto e metafisica nella morale di Africano Spir".

- Joseph Segond, "L'idéalisme des valeurs et la doctrine de Spir" in: Revue philosophique de la France et de l'étranger, 1912, 8, p. 113–139.

- Samuel Spitzer, Darstellung und Kritik der Moralphilosophie Spir's, Raab, 1896.

Spitzer's dissertation at Würzburg. - Andreas Zacharoff, Spirs theoretische Philosophie dargestellt und erläutert, Weida i. Th., Thomas & Hubert, 1910.

Zacharoff's dissertation at Jena. - Mary-Barbara Zedlin, "Afrikan Alexandrovich Spir", in: Paul Edwards ed., Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 544, New York, Macmillan, 1972.

- Selected works on Nietzsche's relationship to Spir

- Peter Bornedal, The Surface and the Abyss, Nietzsche as Philosopher of Mind and Knowledge, Berlin – New-York, 2010.

- Hélène Claparède-Spir, Evocation: Tolstoi, Nietzsche, Rilke, Spir, Genève, Georg, 1944.

- Hélène Claparède-Spir, "Friedrich Nietzsche und Afrikan Spir", Philosophie und Leben, 1930, 6, p. 242–250.

- Maudemarie Clark & David Dudrick, "Nietzsche's Post-Positivism", European Journal of Philosophy, 2004, 12, p. 369–385.

- Karl-Heinz Dickopp, "Zum Wandel von Nietzsches Seinsverständnis: Afrikan Spir und Gustav Teichmüller", Zeitschrift für philosophische Forschung, 1970, 24, p. 50–71.

- Paolo D'Iorio, "La superstition des philosophes critiques: Nietzsche et Afrikan Spir", Nietzsche-Studien, 1993, 22, p. 257–294.

- "La superstizione dei filosofi critici: Nietzsche e Afrikan Spir". Hyper Nietzsche.

- Domenico M. Fazio, "Il Pensiero del Giovane Nietzsche e Afrikan Spir", in: Bollettino di Storia della Filosofia dell'Università degli Studi di Lecce, 1986/9, 9, p. 243–262.

- Domenico M. Fazio, Nietzsche e il criticismo, Elementi kantiani e neokantiani e critica della dialettica hegeliana nella formazione filosofica del giovane Nietzsche, Urbino, QuattroVenti, 1991.

- Michael Steven Green, Nietzsche and the Transcendental Tradition, Urbana & Chicago, University of Illinois Press – International Nietzsche Studies Series, 2002.

- Michael Steven Green, "Nietzsche’s Place in Nineteenth Century German Philosophy", Inquiry, 2004, 47, p. 168–188.

Review of Will Dudley, "Hegel, Nietzsche, and Philosophy: Thinking Freedom", Cambridge U. Press 2002. - Michael Steven Green, "Was Afrikan Spir a Phenomenalist?: And What Difference Does It Make for Understanding Nietzsche?", The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, v46, n2, 2015, p. 152–176.

- Nadeem J. Z. Hussain, "Nietzsche's Positivism", European Journal of Philosophy, 2004,12, p. 326–368.

- Sergio Sánchez, "Logica, verità e credenza: alcune considerazioni in merito alla relazione Nietzsche–Spir" in: Maria Cristina Fornari (ed.), La trama del testo: Su alcune letture di Nietzsche, Lecce, Millela, 2000, p. 249–282.

- Sergio Sánchez, "Linguaggio, conoscenza e verità nella filosofía del giovane Nietzsche: I frammenti postumi del 1873 e le loro fonti", Annuario Filosofico, 2000, 16, p. 213–240.

- Sergio Sánchez, El problema del conocimiento en la filosofía del joven Nietzsche, Córdoba (Argentina), 2001

- Karl Schlechta & Anni Anders, Friedrich Nietzsche: Von den verborgenen Anfängen seines Philosophierens, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt, F. Frommann, 1962, p. 119–122, 159–166.

- Robin Small, "Nietzsche, Spir, and Time",Journal of the History of Philosophy, 1994, 32, p. 82–102.

Reprinted in Chapter One of Robin Small, Nietzsche in Context, Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2001.

External links

- Claparède-Spir Family Papers at Harvard University Library

- Online version of Spir's Thought and Reality, 2d ed., 1877 (in German)

- Pensée et Réalité, 1896 (transl. of Thought and Reality) at Bibliothèque nationale de France (in French)

- Esquisses de Philosophie critique, 1887, at Bibliothèque nationale de France (in French)

- Paroles d'un sage, Paris-Genève, 1937 (in French)

- American website on Spir

- Article on African Spir (in Russian)

- Article on African Spir in a biographic dictionary (in Russian)

- Kirovohrad Regional Universal Research Library's Website on Spir (mostly in Ukrainian)

- Letters of Leo Tolstoy (in Russian)

- Book of Michael Steven Green, Nietzsche and the Transcendental Tradition (on African Spir-Nietzsche relationship)

- Fazio's article on African Spir-Nietzsche relationship Archived 11 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Italian)