Menelik's Invasions

Menelik's Invasions, also known as the Agar Maqnat (Amharic: "cultivation of land") were a series of wars and conquests carried out by Menelik II of Shewa to expand the Ethiopian Empire.[1]

| Menelik's Invasions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The cover of French magazine Le Petit Journal, depicting the Ethiopians overrunning Somalis | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Amir Abdullahi Gaki Sherocho Kawo Tona Gaga and others... | ||||||

In 1866 Menelik II became the king of Shewa, and in 1878 began a series of wars to conquer land for the Ethiopian Empire and to increase Shewan supremacy within Ethiopia. Menelik II sought to build a "greater Ethiopia" and to incorporate lands from the era of Amda Seyon I, prior to the Ethiopian–Adal War and Oromo migrations.[2] He is viewed as the founder of modern Ethiopia.[3][4]

Gurageland

In the late 1870s Menelik led a campaign to incorporate the lands of the Gurage people into Shewa. In 1878, the Soddo Gurage living in Northern and Eastern Gurageland peacefully submitted to Menelik and their lands were left untouched by his armies, likely due to their shared Ethiopian Orthodox faith and prior submission to Negus Sahle Selassie, grandfather of the Emperor. However, in Western Gurageland which was inhabited by the Sebat Bet, Kebena and Wolene fiercely resisted Menelik.[5] They were led by Hassan Injamo of Kebena who on the advice of his sheiks declared jihad against the Shewans. For over a decade Hassan Injamo fought to expel the Shewans from the Muslim areas of Gurage until 1888 when Gobana Dacche faced him in the Battle of Jebdu Meda where the Muslim Gurage army was defeated by the Shewans, and with that all of Gurageland was subdued.[6][7]

Arsi

Conflicts between the Kingdom of Shewa and the Arsi Oromo date back to the 1840s when Sahle Selassie led an expedition against the Arsi. Shewans rulers had longed to pacify and incorporate this territory into their realm. In 1881, Menelik led a campaign against the Arsi Oromo, this campaign proved difficult, as the Oromos abandoned their homeland to wage gurriella war against the Shewan army, the Arsi inflicted significant losses against Menelik's forces through ambushes and raids. Menelik eventually left Arsi territory and his uncle Darge Sahle Selassie was left incharge of the campaign. In September 1886, Darge faced a large Arsi force at the Battle of Azule, the result was an overwhelming Shewan victory as the Arsi Oromo were completely defeated by the Shewan army. After the defeat of the Arsi at Azule the province of Arsi was pacified and Darge was named its governor.[8][9][10]

Harar

In 1886 an Italian explorer and his entire party were massacred by soldiers from the Emirate of Harar, giving the Negus an excuse to invade the Emirate of Harar. The Shewans then led an invasion force, however when this force was camped in Hirna the small army of Emir Abdullah II shot fireworks at the encampment, startling the Shewans and making them flee towards the Awash River during the Battle of Hirna.

Menelik II wrote to European powers: "Ethiopia has been for 14 centuries a Christian island in a sea of pagans. If Powers at a distance come forward to partition Africa between them, I do not intend to remain an indifferent spectator."[11] He did not, sending word to Emir Abdullah, ruler of the historic city of Harar which was pivotal to Muslim East Africa, to accept his suzerainty. The Emir suggested that Menelik should accept Islam. Menelik promised to conquer Harar and turn the principal mosque into a church, saying "I will come to Harar and replace the Mosque by a Christian Church. Await me." The Medihane Alam Church is proof Menelik kept his word.[12][13][14]

In 1887 the Shewans sent another large force personally led by Menelik II to subjugate the Emirate of Harar. Emir Abdullah, in the Battle of Chelenqo, decided to attack early in the morning of Ethiopian Christmas assuming they would be unprepared and befuddled with food and alcohol, but was defeated as Menelik had awoken his army early expecting a surprise attack. The Emir then fled to the Ogaden and the Shewans conquered Hararghe.[15][16]

Finally having conquered Harar, Menelik extended trade routes through the city, importing valuable goods such as arms, and exporting other valuables such as coffee. He would place his cousin, Makonnen Wolde Mikael in control of the city. Harari oral tradition recounts 300 Hafiz and 700 newly-wed soldiers killed by Menelik's forces in the short battle. The remembrance of the seven hundred "wedded martyrs" became part of Harari wedding customs to this day, when every Harari groom is given fabric that is called "satti baqla" in Harari, which means "seven hundred." It's a rectangular cloth from white woven cotton ornamented with a red stripe along the edges symbolizing the martyrs' murders. When he presents it, the giver (who usually is the paternal uncle of the woman's father), whispers in the ear of the groom: "So that you do not forget.[17][18]

The largest Mosque in Harar (known as Sheikh Bazikh, "The capital Mosque," or Raoûf), located in Faras Magala, and the local Madrassa were turned into churches, notably "Medhane Alem church" in 1887[19] by Menelik II after the conquest.[20]

Welayta

In 1890 Menelik II invaded the Kingdom of Wolayta. The war of conquest has been described by Bahru Zewde as "one of the bloodiest campaigns of the whole period of expansion", and Wolayta oral tradition holds that 118,000 Welayta and 90,000 Shewan troops died in the fighting.[21] Kawo (King) Tona Gaga, the last king of Welayta, was defeated and Welayta conquered in 1896. Welayta was then incorporated into the Ethiopian Empire. However, Welayta had a form of self-administrative status and was ruled by governors directly accountable to the king until the fall of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974.[22][23]

Kaffa

The Kingdom of Kaffa was a powerful kingdom located south of the Gojeb river in the dense jungles of the Kaffa mountains. Due to constant invasions from the Mecha Oromos, the Kafficho people developed a very unique defense system unlike anything seen in the Horn of Africa. The Kafficho built very deep trenches (Hiriyoo) and ditches (Kuripoa) along the borders of the kingdom to prevent intruders from entering. They also used natural barriers such the Gojeb River and the mountains to repel invaders. As a result, Kaffa earned a reputation of being impenetrable and inaccessible to outsiders.[24]

In 1895 Menelik II ordered the Kingdom of Kaffa to be invaded and sent three armies led by Dejazmach Tessema Nadew, Ras Wolde Giyorgis and Dejazmach Demissew Nassibu supported by Abba Jifar II of Jimma (who submitted to Menelik) to conquer the mountainous kingdom. Gaki Sherocho the king of Kaffa hid in the hinterlands of his kingdom and resisted the armies of Menelik II until he was captured in 1897 and exiled to Addis Ababa. After the kingdom was conquered Ras Wolde Giyorgis was named it's governor.[25]

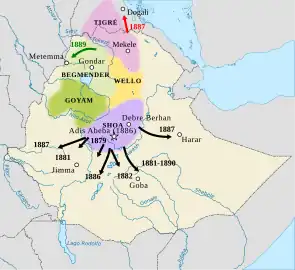

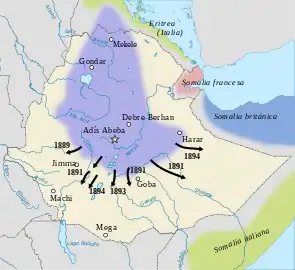

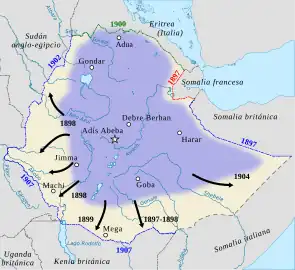

Maps

1879–1889.

1879–1889. 1889–1896.

1889–1896. 1897–1904.

1897–1904.

References

- Bereketeab, Redie (28 March 2023). Historical Sociology of State Formation in the Horn of Africa. Springer International Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 9783031241628.

- The Making of Modern Ethiopia: 1896-1974. The Red Sea Press. 1995. ISBN 9781569020012.

- Selassie, Tsehai Brhane (1975). "The question of Damot and Wälamo". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 13 (1): 37–46. JSTOR 41965880.

- Richard Pankhurst The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century – Google Books", 1997. p. 284.

- "The Introduction and Legacy of Menelik's life". 20 August 2018.

- "Change and Continuity of TraditionalSystem of Governance: The Case of Oget among the Qebena, South Ethiopia".

- "Fanonet: Ethnohistorical Notes on the Gurage Urban Migration in Ethiopia" (PDF).

- "Conquest and Resistance in the Ethiopian Empire, 1880 - 1974: The Case of the Arsi Oromo". The Arsi Oromo Resistance against Ethiopian Imperial Conquest (1880–1900). Brill. 23 January 2014. ISBN 9789004265486.

- Gnamo, Abbas (23 July 2014). Conquest and Resistance in the Ethiopian Empire, 1880 - 1974: The Case of the Arsi Oromo. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-25813-6.

- Tafla, Bairu (July 1975). "Ras Dargé Sahle Selassie, c 1827 - 1900". The Journal of African History. 13 (2): 17–37.

- Akbar, M. J. (2010-12-01). Have Pen, Will Travel. Roli Books Private Limited. ISBN 978-81-7436-993-2.

- Have Pen, Will Travel, M.J. Akbar, 2010

- Selassie, Bereket H. (2007). The Crown and the Pen: The Memoirs of a Lawyer Turned Rebel. Red Sea Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-56902-276-4.

- Sauldie, Madan M. (1987). Super Powers in the Horn of Africa. APT Books. ISBN 978-0-86590-092-9.

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (2003). "Ugas Nuur". Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1.

- Harold G. Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia 1844-1913, (Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press, 1995), p. 91 ISBN 1-56902-010-8

- HISTORY OF HARAR AND THE HARARIS, REFINED VERSION, REFINED BY WEHIB M. AHMED (DUA’LE), HARARI PEOPLE REGIONAL STATE CULTURE, HERITAGE AND TOURISM BUREAU, October 2015/2008 EC. HARAR https://everythingharar.com/files/History_of_Harar_and_Harari-HNL.pdf

- Feener, R. Michael (2004-10-26). Islam in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-57607-516-6.

- Apotsos, Michelle Moore (2021-07-29). The Masjid in Contemporary Islamic Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-61799-4.

- Harar Jugol (Ethiopia), UNESCO, p.28, p.30 https://whc.unesco.org/document/151989

- Sarah Vaughan, "Ethnicity and Power in Ethiopia" Archived 2011-08-13 at the Wayback Machine (University of Edinburgh: Ph.D. Thesis, 2003), p. 253.

- Sarah Vaughan, "Ethnicity and Power in Ethiopia" Archived 2011-08-13 at the Wayback Machine (University of Edinburgh: Ph.D. Thesis, 2003), p. 253.

- Yimam, Baye (2002). Ethiopian studies at the end of the second millennium. Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University. p. 930. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- "Hisotorical glimpse of Hiriyoo". 2021. S2CID 234070093.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - "ETHIOPIA THROUGH RUSSIAN EYES". Archived from the original on 14 April 2014.