Aging of the United States

In recent decades, the fertility rate of the United States has declined below replacement level, prompting projections of an aging population and workforce,[1][2] as is already happening elsewhere in the developed world and some developing countries.[3] Nevertheless, the rate of aging in the United States remains slower than that seen in many other countries,[4][5] including some developing ones,[3] giving the nation a significant competitive advantage.[6][7][8][9] Still, it remains unclear how population aging would affect the United States.

History

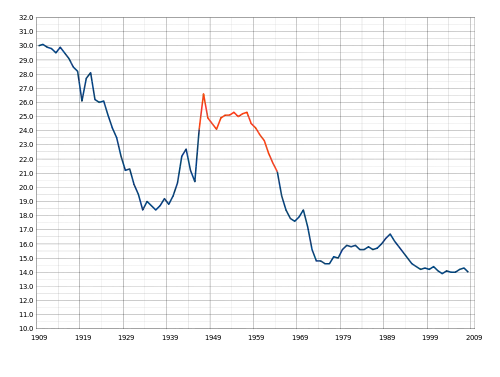

The birth rate in the United States has declined steadily since the beginning of the nineteenth century, when the average person had as many as seven children.[10] Americans of all ethnic groups and socioeconomic classes had fewer children towards the end of the nineteenth century.[11]

In a 1905 speech, President Theodore Roosevelt criticized Americans for having fewer children, and described the declining birth rate as a "race suicide" among Americans,[12] quoting eugenicist Edward Alsworth Ross.[13][14] During the 1930s, the Great Depression caused a substantial decrease in the birth rate, but this trend was reversed in the subsequent Baby Boomer generation,[15] thanks to highly favorable economic conditions.[16] Towards the end of the twentieth century, however, the prevalence of childlessness—voluntary and otherwise—increased.[16]

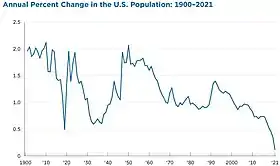

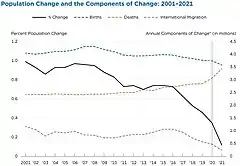

While U.S. fertility rates were roughly at replacement level during the 1990s and early 2000s, contrary to expectations, they never rebounded after the 2007-2009 Great Recession even though the U.S. economy had recovered.[17][18][19] During the second half of the 2010s, the rate of growth of the U.S. population was in steady decline.[20] Between the 2000s and 2020, all states except North Dakota saw a decline in fertility.[21] As of 2019, no states except North Dakota and Utah were at or above replacement fertility.[1] The 2020 Census reveals that the number of Americans aged five or younger is lower than in 2010.[22][23] More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic caused fertility to decline further,[15][24][25] a "bump" in 2021 notwithstanding,[26] while also increasing the death rate in the country.[27] At the same time, many women are choosing delay childbearing or are choosing a childless life altogether.[28][29] By 2022, the total fertility rate of the United States stood at 1.66.[30] The rate of population growth in the early 2020s was at a historic low, driven mainly by immigration.[31] Millennials are the most reluctant generation in history when it comes to reproduction.[32][33] Between 1990 and 2015, the number of married couples aged 18 to 34 with children dropped from 37% to 25%.[34] The number of American women who do not have children by the age of 30 has grown, breaking previous fertility trends where younger women made up the bulk of births. While only 10% of women were childless in 1976 at the end of their reproductive years, it is projected that 25% of those born in 1992 will reach the same benchmark in 2032.[35] Longitudinal analysis suggests that American women are not merely postponing having children but are increasingly avoiding it altogether.[5] However, among Millennial women who have given birth, the average fertility rate is about 2.02 children per woman.[33]

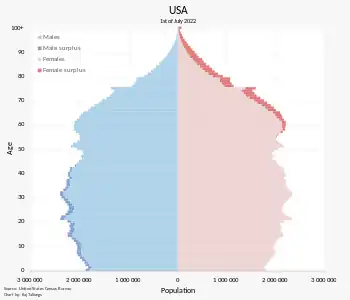

Regardless, U.S. birth rates have been on the decline across virtually all age groups, socioeconomic classes, and races since the late 2000s.[36] This trend could cause the general population of the country to age significantly in the future.[24] The oldest Baby Boomers, a large demographic cohort, had started to reach retirement age in the 2010s.[20] By the early 2020s, about one in six Americans are 65 or older.[37] In 2020, the median age of the United States is 38.8, up from 37.2 in 2010,[23] 35 in 2000, and 30 in 1980.[38] An increase in median age is seen among all ethnic groups, though European Americans are currently the oldest by that measure, followed by African Americans and Asian Americans (including Amerindians and Native Alaskans);[20] Hispanic and Latino Americans are the youngest.[23] Maine (median age 44.8) and New Hampshire (43.3) are the oldest states in the Union, while Texas (35.5), the District of Columbia (34.8), and Utah (31.9) are the youngest.[38]

In the modern world, it has become common for developed countries to fall below the replacement level of births or see population decline. Many of these countries have tried to launch government initiatives to combat this trend, including large cash incentives for having more children, but these programs have been largely ineffective.[39] Nevertheless, American women tend to have their first children at an earlier age and end up having more children than their counterparts from other developed countries even though the U.S. does not have social welfare programs that are as generous as other rich nations.[5][40]

Given 2020 demographic trends, it is projected that the U.S. population would grow slightly by 2100, while other countries, including China and India, would shrink.[3] However, the number of Americans aged 65 and over will exceed that of children below the age of 18, according the U.S. Census Bureau.[41]

Causes

Population aging and falling birth rates in the US is driven by a variety of factors, including increased access to birth control, growing awareness of the realities of parenthood (especially motherhood), and changing societal attitudes toward reproduction, resulting in lower fertility among modern Americans.[42][26][43] In the United States today, while the number of single parents has grown, most people still have children within wedlock.[44]

But even married couples are less likely to have children, at least not right away, as the childfree lifestyle continues to gain traction.[43] The number of unintentional pregnancies has decreased,[25][45] though the rate still stood at 45% in 2018.[46] Adolescent pregnancies, most of which are unintentional, also fell.[47] Compared to a peak of 96.3 births per 1000 females aged 15 to 19 in 1957, when people married and had children early, the adolescent birth rate plummeted to 17.3 in 2018.[48] (Black and Hispanic teenagers had the largest decline,[49] though they were still above whites and Asians.[48]) Twenty-first-century American youths are more likely to have access to effective and long-acting methods of contraception, such as an intrauterine device (IUD), and to be more cautious about sexual intercourse than their predecessors.[48][50]

While economic troubles and climate anxiety are commonly cited reasons,[51] data suggest they are not the primary factors behind falling fertility in the U.S. Rather, it is due to changing attitudes; today's young people, especially women, tend to prioritize and expect more from their careers and are less interested in having children.[52] According to the Pew Research Center, the number of non-parents aged 18 to 49 who do not expect to have any children has grown. Among them, a lack of interest in children, medical issues, and financial problems were the top reasons for their predictions.[53]

As parenthood continues to lose its appeal, more and more Americans prefer their own careers, leisure time, savings, and personal freedom to having children and fewer consider children to be a source of happiness or fulfillment.[36][26][54] Among those with children, some have chosen not to have more either because they do not want them, because they would like to spend more time with the ones they already have, or because could not afford more children.[18][53] In fact, many admit that their financial circumstances would improve once their children leave the house and that they would be better off not having children.[26] Among those having fewer children than they would like, concerns over the state of the economy and personal financial security are common and many believe the cost of raising a child is too high.[18] More and more women are realizing that having children is an option they can ignore in favor of economic or educational opportunities; some worry that a woman's career might stall if she chooses to have children.[18][36][40] The number of American women earning university degrees has grown relative to men's since the late 2000s, coinciding with the long-term decline in birth rates.[36] Globally, gender equality is associated with lower fertility.[18]

In the early 2020s, as many as one in five American adults do not want to have children, with some reporting they had made their decision early on.[55][56] It remains unclear whether they would change their minds.[18] Data dating back to the 1980s show that this is part of a long-term trend, possibly starting with the Baby Boomers, who were the first cohort to begin questioning social norms on family formation. Furthermore, dedication to work and modern expectations of parents have increased the opportunity cost of having a child.[5][36] Because of the aforementioned reasons, the birth rates of women of all age groups (except those in their forties), races, and educational levels have fallen.[52] The number of European Americans has been shrinking since 2016 while the rates of growth of people of other races have fallen as well, except for those of mixed heritage. Overall, the fall of the European-American and youth populations is the biggest factor behind the aging of the United States. But this trend is moderated by the growth of non-white ethnic groups.[20]

Another major cause of population aging in the United States is the fact that the Baby Boomers, a large cohort, are getting older, adding a large group of older Americans to the population and causing the median age to move up. Although many Baby Boomers began reaching retirement age in the early 2010s, many of this cohort's youngest members are still several years away from retirement and remain successfully employed or are eligible for and seeking new jobs.[4][57]

Impacts

Recent research studies have documented that between 50% and 80% percent of Americans aged 50 or older have personally experienced or witnessed at least one episode of age discrimination in the workplace, with roughly 20% excluded from hiring or promotion and nearly 10% terminated from their jobs due to their age, despite federal and state protections for workers over the age of 40.[58][59][60]

By 2030, 20% of Americans are projected to be 65 and older.[61] Both the overall population of the country and the average age are projected to increase over coming years. Given that older people tend to need more health services, some demographers have theorized a significant impact on the country resulting from these trends.[27] Population aging could create an increasing need for services such as nursing homes and care-giving.[27]

Economy

A shortage of workers is expected in the U.S. workforce due to a declining labor participation rate. Projections show that the demand for labor needed now is not being fulfilled, and the gap between labor needed and labor available will continue to expand over the future.[62][63] Owing to the relatively large size population size of those born between the end of WWII and the mid-1960s (referred to by some as the "Baby Boomers"), the number of people generally considered to be of working age is declining.[62][63] The retirement of members of the aging workforce could possibly result in the shortage of skilled labor in the future.[64][65] A majority of experienced utility workers and hospital caregivers, for example, will be eligible for retirement.[65]

By the late 2010s, the United States found itself facing a shortage of tradespeople,[66][67] a problem that persisted in the early 2020s despite the COVID-19 pandemic-induced recession and prospective employers offering higher salaries and paid training.[68] Having an aging population accelerates industrial automation.[69][70] Experts expect the labor crunch of the early 2020s to continue for years to come, due to not just the Great Resignation, but also the aging of the U.S. population,[71] the decline of the labor participation rate,[72] and falling rates of legal immigration.[72] During the Great Recession, population aging alone cost the United States 1.7 million workers, reckoned the Peterson Institute for International Economics.[73]

From a demographic point of view, the labor shortage in the United States during the 2020s is inevitable due to the sheer size of the baby boomers.[74][75] As the oldest economically active cohort,[75] the baby boomers comprised about a quarter of the U.S. workforce in 2018.[76] Though they were projected by economists to begin retiring in the 2010s,[74] 29% of older (65–72 years of age) baby boomers in the United States remained active in the labor force in 2018, a large portion compared to older cohorts at the same age.[77] Employment rates among older workers are increasing.[78] In fact, the share of people who continue working after turning 65 is relatively high in the US, when compared to other developed countries.[79]

The official age of retirement in the United States had already been raised, and Baby boomers were incentivized to postpone retirement in part because it allowed them to claim more Social Security benefits once they finally retired.[77] Furthermore, large numbers would like semi-retirement arrangements or flexible work schedules.[80]

The COVID-19 pandemic however, may have sped up the retirement of some baby boomers.[81] The Pew Research Center reported that the number of baby boomers in retirement had increased by 3.2 million in 2020, the largest annual increase in the previous decade.[81] But even before the pandemic, the United States had a gap between the number of job openings and the number of unemployed people.[82][72] Like most other members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the U.S. has seen its productivity growth falter and its debt as a share of GDP grow due to demographic trends.[83] Having an aging population and a labor shortage makes it more difficult to curb inflation.[84]

A shrinking birth rate could exacerbate economic inequality by increasing the importance of family inheritance,[85] while an overall decrease in the population could shrink the economy by reducing the demand for basic goods like groceries and real estate.[86][87] On the other hand, having fewer or no children has enabled women to pursue more opportunities outside the home.[5] In fact, places with the highest job growths in the 2010s saw the biggest drops in fertility. For women in such places, the opportunity cost of having a child was higher.[36] Moreover, people without children do not need to save money to pass on to their children and as such can afford to work fewer hours per week and retire early.[88]

Nevertheless, unlike their counterparts in many other countries East and West, American Baby Boomers had many children of their own, the Millennials, who are a large cohort relative to the nation's population and are themselves having a relatively high birth rate, as of the 2010s.[89] Millennials and Generation Z have been responsible for a surge in labor participation in the U.S. as the same time as the contraction of the workforce of major economies.[90] Indeed, the U.S. workforce is projected to grow by 10% by 2040,[7] and should not decline before 2048.[91] However, young people are spending more time in education and training and are entering the workforce at a later age. A loss in skilled and capable workers has made it harder for employers to recruit new staff.[92]

Having a relatively young, diligent, and productive workforce means that the United States will continue to have a significant number of consumers, investors and taxpayers in the upcoming decades. This gives the nation an economic edge over others.[9][89] As of 2022, despite demographic trends, most U.S. states were in a fiscally healthy position; some even had budget surpluses.[21] However, a sustained sub-replacement fertility and low rates of migration will lead to an aging population, a potential indicator that the U.S. economy could be less dynamic, innovative, and productive than it was in the past.[87][2] By 2023, shortages of highly skilled workers are already jeopardizing the Joe Biden administration's plan to rejuvenate the American manufacturing sector.[93] In addition, some women could make the decision to give up working in order to take care of their family members, exacerbating the labor shortage.[94]

Education

By the early 2020s, enrollment in K-12 public schools has fallen, partly due to the switch to private schools and home schooling, but also due to a smaller number of school-aged children (5-17).[95]

In the 1970s, American colleges and universities saw a dramatic increase in enrollments due to the post-war baby boom and the growth of women in higher education and the work force. By the 1980s and 1990s, although the baby boom had long ended, institutions continued to enjoy good fortune due to growing demand. But this all changed in the aftermath of the Great Recession, which saw significant cuts in funding for education and falling birth rates.[96] Due to declining birth rates, the number of American high-school graduates is expected to drop after 2025, putting more pressure on institutions of higher learning at a time when many have already been permanently shut down.[97][98] The decline of college enrollment is projected to accelerate in the 2030s.[99] Many private colleges will not survive.[17] Public universities are struggling to convince state and local governments to keep funding them[17] and have downsized or merged to curb costs.[100] Demand for education from the nation's top 100 colleges and universities, however, is likely to remain high, in part because of rising numbers of Indian and Chinese Americans, for whom higher education is of utmost importance.[17] In any case, market trends are forcing the higher-education sector to innovate, which is something it has not traditionally been good at.[100] To survive, non-elite institutions will have to cut back or eliminate courses in the liberal arts and humanities, like gender studies,[101] and expand those in emerging fields, such as artificial intelligence,[102] and professional programs, such as law enforcement.[17] They might even have to lower their standards of admissions.[99] Some are also addressing untapped demands, such as mid-career training or continuing education.[100] In addition, Americans who work in higher education are older on average than the average American worker. In the future, this sector of the economy will need to find ways to retain staff or to encourage retirees to come back (part-time).[103]

There is some research supporting the idea that in well-educated countries, it might actually benefit the population to have a birth rate below replacement levels because people at different ages do not make the same level of economic contributions on average.[104] In the United States, birth rates among teenagers and the lower classes continues to fall, while women with higher incomes and higher education are having more children.[100]

Environment

Some demographers have suggested that a declining birth rate may have net positive effects on the country.[105] Many environmentalists see this trend more optimistically because it could help combat the perceived problem of overpopulation. The world population is expected to reach almost 10 billion by the year 2050, which could pose a burden to Earth's natural resources.[106]

Having fewer children has been shown to be an effective way to reduce environmental impact through reduced carbon footprint and higher populations could increase the effects of climate change in the future.[107][108] Having an expanding population of people who live longer and are wealthier may not be sustainable.[40] Though the details remain debated, in the 2020s, growing numbers of couples have cited climate change as a reason for having fewer or not having children at all.[109][51]

Geopolitics

Many of America's allies—Canada, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand—are themselves aging.[8][91] For that reason, they would struggle to finance their own defense and would become even more dependent on the United States at a time when U.S. demographic advantage is fading.[8] Indeed, while the U.S. maintained a fertility advantage over other developed nations during the 1990s and 2000s, this edge faded away during the 2010s.[110]

To combat this problem, the U.S. needs to improve ties with emerging economies, such as the Philippines, Indonesia, and India,[8] though some of these countries are already in the process of transitioning towards an aging society.[111] The combined GDP of the United States and its allies has shrunk from 77% of the global economy in 2002 to just 56% in 2021, and this trend will likely continue.[91] Furthermore, an aging population will reduce the ability of the United States to participate in global affairs the way it once did.[6]

Nevertheless, because the United States is aging more slowly than any one of its main rivals, it will have an advantage in any future geopolitical contests.[89][112] Given current demographic trends, it is unlikely that the United States will lose its dominant position to China and Russia.[112][8]

China has a low fertility rate compared to the United States.[7] China's median age is expected to exceeds America's by around 2020[113] and the Chinese population has already begun to decline since 2022.[114] China's number of people over 65 as a share of the population is predicted to exceed that of the United States by around 2035.[115] Furthermore, the United States has an advantage that China lacks—immigration. While the U.S. remains an attractive place for immigrants, very few would like to move to China.[7][115] In fact, projections of China's economic growth from the early 2020s taking into account China's population aging, among other problems facing the nation, tend to delay the date at which China's economy will surpass America's. Even if China were to overtake the United States, the latter would soon reclaim its position.[116][117][118]

By one estimate, China's rate of GDP growth will be below America's by the 2030s because its dependency ratio will exceed America's.[91] On one hand, China's demographic decline relative to the U.S. could prompt it to undertake more risky actions, for example with regards to the issue of Taiwanese independence.[119][120] On the other hand, continued U.S. superiority might deter adversaries from taking military actions against either the U.S. or its allies.[112] A "geriatric peace" might be at hand,[6] as the graying powers have an incentive to cooperate in order to maintain the global order before their demographic realities prevent them from doing so.[91]

Occupational safety

Because of the many older adults opting to remain in the U.S. workforce, many studies have been done to investigate whether the older workers are at greater risk of occupational injury than their younger counterparts. Due to the physical declines associated with aging, older adults tend to exhibit losses in eyesight, hearing and physical strength.[65] Data shows that older adults have low overall injury rates compared to all age groups, but are more likely to suffer from fatal and more severe occupational injuries.[65][121] Of all fatal occupational injuries in 2005, older workers accounted for 26.4%, despite only comprising 16.4% of the workforce at the time.[121] Age increases in fatality rates in occupational injury are more pronounced for workers over the age of 65.[121] The return to work for older workers is also extended; older workers experience a greater median number of lost work days and longer recovery times than younger workers.[121] Some common occupational injuries and illnesses for older workers include arthritis[122] and fractures.[123] Among older workers, hip fractures are a large concern, given the severity of these injuries.[123]

Social welfare and healthcare

An aging population has implications for social-welfare programs.[4] The U.S. federal social security system functions through collecting payroll taxes to support older citizens.[65] It is possible that a smaller workforce, coupled with increased numbers of longer-living elderly, may have a negative impact on the social security system. The Social Security Administration (SSA) estimates that the dependency ratio (people ages 65+ divided by people ages 20–64) in 2080 will be over 40%, compared to the 20% in 2005.[65] SSA data shows one out of every four 65-year-olds today will live past the age of 90, while one out of 10 will live past 95. Indeed, 60% of baby boomers are more worried about outliving their savings than dying.[124] Rising life expectancy may result in reductions in social security benefits, devaluing private and public pension programs.[65][125] Were there to be a reduction or elimination of programs such as social security and Medicare, many may need delay retirement and to continue working.[122] In 2018, 29% of Americans aged 65–72 remained active in the labor force, according to the Pew Research Center, as Americans generally expect to continue to work after turning 65. The baby boomers who chose to remain in the work force after the age of 65 tended to be university graduates, whites, and urban residents. That the boomers maintained a relatively high labor participation rate made economic sense because the longer they postpone retirement, the more Social Security benefits they could claim, once they finally retire.[126] However, given current trends (2023), U.S. federal expenditure on programs for the elderly will equal spending on education, research and development, transportation, and national defense combined by 2033. This compounds the problem of soaring public debt.[127]

By 2030, 20% of Americans are predicted to be past the age of retirement, which could pose a burden to the healthcare system. Older and retired people tend to need more health services, which must be provided by their younger counterparts, so some demographers have theorized that this could have a negative impact on the country.[27] Arthritis, cancer, diabetes, obesity, and cognitive issues are among the most common issues faced by Americans over the age of 65.[37] Older adults who have worked in the construction industry have shown high rates of chronic diseases.[125][128] Experts suggest that the number of geriatricians will have to triple to meet the demands of the rising elderly.[129] Demand for other healthcare professionals, such as nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists and dentists is also projected to rise,[129] as well as for common geriatric healthcare needs, such as medications, joint replacements and cardiovascular operations.[129] Between 1966 and 2023, the number of people qualified for Medicare tripled to nearly 65 million, with 10 million seniors and disabled people being added to the system from 2013 to 2023.[130] In the early 2020s, among Americans aged 65 or older, 14% of all expenditures goes to healthcare, compared to 8% for the general population.[37] While some enjoy living by themselves, others suffer from physical or mental health issues being socially isolated.[131]

Between the late 2010s and early 2020s, Millennials and Generation Z joined the workforce in large numbers, allowing the U.S. to maintain a relatively large tax base, alleviating concerns over the financial sustainability of various social-welfare programs.[90] Furthermore, because American welfare programs are less generous than Europe's, they are also less vulnerable to demographic shifts.[73] Nevertheless, in 2023, both Medicare and Social Security as they stand are projected to run out of funds by the late 2020s and mid-2030s, respectively.[130] With the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, the Joe Biden administration sought to curb the cost of medical care by allowing Medicare to negotiate lower costs for certain drugs and treatments, such as insulin.[130]

Society

Population aging can potentially change American society as a whole. Many companies use a system, in which older, tenured workers get raises and benefits over time, eventually hitting retirement.[132] With larger numbers of older workers in the workforce, this model might be unsustainable. In addition, perceptions of older adults in society will change, as the elderly are living longer lives and more active than before.[129][133] Changing from a youth-focused culture to having a more positive attitude towards aging and being more respectful of seniors like Japan can help elderly Americans extend their life span and live out their sunset years in dignity. American society will have to confront the negative stereotypes of aging and ageism.[133] In order to win elections, politicians will have to be more attentive towards the elderly.[134]

In his work on elite overproduction, social scientist Peter Turchin notes that because given U.S. demographic realities, the youth bulge would likely not fade away before the 2020s, making this time period prone to sociopolitical turbulence.[135]

Proposed solutions

.jpg.webp)

A number of solutions have been proposed to address the problems caused by an aging population. Investing in technological and human-capital development in order to enhance productivity might help the United States offset some of the economic effects of population aging.[5][30] Raising the retirement age, further automation, and encouraging higher labor participation rates among women could help alleviate the labor shortage, with the latter successfully done in Japan in the 2010s.[110] Policies aimed at raising workforce participation among those of prime working age in general is another potential solution,[73] as are giving older people incentives to continue working in appropriate sectors where there is a labor shortage, such as teaching,[41] and recruiting former convicts.[136] Cities could render themselves friendlier towards the elderly, for example by improving public transit,[137] promoting healthy lifestyle choices (physical activities, learning, and social engagement), adding green spaces and recreational facilities.[41] Initiatives such as communal grand parenting programs, found in Finland, could help engage the elderly on one hand and help young people on the other.[41] In Southeast Asia, self-help clubs offer seniors opportunities for friendship and social activities.[41] In Zimbabwe, the elderly are recruit to help younger people handle mental-health issues. (Those with serious problems are referred to professionals.)[41] To deal with the increased demand that could be placed on the healthcare system, telehealth and virtual health monitoring has arisen as a way to help support a larger population of older adults.[138][41] The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has proposed 60 different policy options on how to save billions of dollars on Medicare, such as raising monthly premiums. As of 2023, members of Congress are considering various options to salvage Medicare and Social Security, such as addressing fraud in the Medicare Advantage program and raising the ages of legibility for Medicare and Social Security.[130] Unfortunately, neither raising taxes nor cutting services is politically palatable, something both major parties have learned from experience. Meanwhile, public debt continues to grow, reaching 250% of GDP by mid-century, according to a 2023 projection by the CBO. That year, it stands at 117% of GDP.[127] As has already been done in a number of European countries, the United States could streamline the process of tracking retirement savings, or 401(k).[41] In Japan, a national long-term-care insurance policy was introduced in 2000.[41]

Alternatively, some people have advocated for offering more paid parental leave and child care, thereby encouraging people to have more children.[86] These policies have already been employed in other areas of the world, but with limited results at best.[110] In some countries such as Germany and Czech Republic they successfully raised the birth rate,[139] but not enough to reach replacement level and at a significant cost.[5] On the other hand, such policies failed in Finland,[140] Singapore,[141] Taiwan,[142] Japan, and South Korea.[143] It is unlikely that similarly pro-natalist policies would work in the U.S.,[52] which maintains a relative high fertility rate despite not having social welfare programs that are as generous as some other developed countries.[5]

Some have argued that reduced immigration will have a larger impact on population growth than the declining birth rate.[144] Immigration has historically been a source of growth for the US, and some have suggested that it could slow or reverse the trend of population aging or decline.[145] However, studies have shown that immigrants from countries with high-fertility rates often have fewer children when they immigrate to a country where small families are the norm,[146] and this patterns also holds in the U.S.[19] It has also been shown that low-birth rates[147] and sudden increases in immigration often lead to increased levels of populism and xenophobia.[148] Arguments in favor of increasing immigration to combat declining population levels have sparked outcry from some right-wing political factions in the United States and some European countries.[2][149][150] In the United States, past episodes of domestic turmoil have led to moratoriums on immigration.[8] Furthermore, critics argue that the United States today struggles to integrate the various different ethnic groups already living in the country alongside new immigrants. Political scientist Robert Putnam argues that ethnic and cultural diversity has its downsides in the form of declining cultural capital, falling civic participation, lower general social trust, and greater social fragmentation.[151] Since 1996, there have been numerous failed attempts to introduce comprehensive immigration reforms,[115] and while many continue to view immigration as a net benefit to the nation, the American people remain mixed on whether or not they support more immigration in general.[152] Mass migration is politically problematic.[2] Still, high-skilled immigration, the type of immigration that tends to expand the tax base the most, as has been done in Canada, can help.[110] In fact, the U.S. currently faces a shortage of high-skilled workers in STEM, and foreign talents must navigate difficult hurdles in order to immigrate. Meanwhile, some other countries, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, have introduced programs to attract talents at the expense of the United States.[153]

Some states have relaxed restriction on child labor, but, like immigration, this has proven to be controversial.[136]

References

- Howard, Jacqueline (January 10, 2019). "US fertility rate is below level needed to replace population, study says". CNN. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- Smith, Noah (May 5, 2021). "Why America's Population Advantage Has Evaporated". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- Gallagher, James (July 15, 2020). "Fertility rate: 'Jaw-dropping' global crash in children being born". BBC. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- Friedman, Uri (June 28, 2014). "The End of the Age Pyramid". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- Kearney, Melissa S.; Levine, Phillip B.; Pardue, Luke (Winter 2022). "The Puzzle of Falling US Birth Rates since the Great Recession". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 336 (1): 151–76. doi:10.1257/jep.36.1.151.

- Haas, Mark L. (Summer 2007). "A Geriatric Peace? The Future of U.S. Power in a World of Aging Populations". Quarterly Journal: International Security. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Harvard Kennedy School. 32 (1): 112–147. doi:10.1162/isec.2007.32.1.112. S2CID 57565667.

- Levine, Steve (July 3, 2019). "Demographics may decide the U.S-China rivalry". Axios. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- Eberstadt, Nicholas (July–August 2019). "Why Demographics Will Drive Geopolitics". Foreign Affairs (July/August 2019). Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- "The lessons from America's astonishing economic record". The Economist. April 13, 2023. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- "United States: fertility rate 1800–2020". Statista. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- Heffington, Peggy O’Donnell (May 6, 2023). "Why Women Not Having Kids Became a Panic". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- "II. On American Motherhood by Theodore Roosevelt. America: III. (1861–1905). Vol. X. Bryan, William Jennings, ed. 1906. The World's Famous Orations". www.bartleby.com. Archived from the original on January 8, 2004. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- Dyer, Thomas G. (July 1, 1992). Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race. LSU Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8071-1808-5. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- Lovett, Laura L. (November 30, 2009). Conceiving the Future: Pronatalism, Reproduction, and the Family in the United States, 1890–1938. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-8078-6810-2. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- "What's behind the falling U.S. birthrate?". University of Michigan News. May 13, 2021. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- Frejka, Tomas (2017). "Childlessness in the United States". In Kreyenfeld, M.; Konietzka, D. (eds.). Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences. Demographic Research Monographs. Springer. pp. 159–179. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7_8. ISBN 978-3-319-44665-3. S2CID 152251246.

- Barshay, Jill (September 10, 2018). "College students predicted to fall by more than 15% after the year 2025". Hechinger Report. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- Miller, Claire Cain (July 5, 2018). "Americans Are Having Fewer Babies. They Told Us Why". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- Nawaz, Anna (May 17, 2018). "The surprising thing about the declining U.S. birth rate". PBS Newshour. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- Frey, William H. (August 1, 2022). "White and youth population losses contributed most to the nation's growth slowdown, new census data reveals". Brookings Institution. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- Chapman, Jeff (December 5, 2022). "The Long-Term Decline in Fertility—and What It Means for State Budgets". Pew Trusts. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- Blakeslee, Laura; Rabe, Megan; Caplan, Zoe; Roberts, Andrew (May 25, 2023). "Age Profiles of Smaller Geographies Don't Always Mirror the National Trend". An Aging U.S. Population With Fewer Children in 2020. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- Schneider, Mike (May 25, 2023). "With population of aging Americans growing, U.S. median age jumps to nearly 39". PBS Newshour. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- Mendez, Rich (May 5, 2021). "U.S. birth and fertility rates in 2020 dropped to another record low, CDC says". CNBC. Archived from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- "With a potential 'baby bust' on the horizon, key facts about fertility in the U.S. before the pandemic". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- Leonhardt, Megan (October 18, 2022). "No kids, no problem—millennials break from tradition and embrace being child-free". Fortune. Archived from the original on October 25, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- Meola, Andrew. "The aging US population is creating many problems—especially regarding elderly healthcare issues". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- Bureau, US Census. "Childlessness Rises for Women in Their Early 30s". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- Livingston, Gretchen (May 7, 2015). "Childlessness". Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- Kearney, Melissa (December 29, 2022). "America's shrinking population is here to stay". Financial Times. Archived from the original on December 29, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- Gebeloff, Robert; Goldstein, Dana (December 22, 2022). "U.S. Population Ticks Up, but the Rate of Growth Stays Near Historic Lows". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- Paquette, Danielle (April 28, 2015). "Millennial women are the slowest to have babies of any generation in U.S. history". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- Barroso, Amanda; Parker, Kim; Bennett, Jesse (May 27, 2020). "As Millennials Near 40, They're Approaching Family Life Differently Than Previous Generations". Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- Nova, Annie (October 25, 2018). "Waiting longer to buy a house could hurt millennials in retirement". CNBC. Archived from the original on October 25, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- "The Rise of Childless America". Institute for Family Studies. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- Tavernise, Sabrina; Miller, Claire Cain; Bui, Quoctrung; Gebeloff, Robert (June 16, 2021). "Why American Women Everywhere Are Delaying Motherhood". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- Searing, Linda (February 14, 2023). "More than 1 in 6 Americans now 65 or older as U.S. continues graying". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- Goldstein, Dana (June 22, 2023). "The U.S. Population Is Older Than It Has Ever Been". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- "The U.S. birthrate is falling. Here's how other countries have tried to persuade people to have more children". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- Filipovic, Jill (June 27, 2021). "Women Are Having Fewer Babies Because They Have More Choices". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- Tergesen, Anne (November 16, 2022). "10 Innovations From Around the World to Help Deal With an Aging Population". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 17, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- Nargund, G. (2009). "Declining birth rate in Developed Countries: A radical policy re-think is required". Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn. 1 (3): 191–193. ISSN 2032-0418. PMC 4255510. PMID 25489464.

- Escobar, Sabrina; Rivas, Teresa (June 3, 2022). "The Wedding Boom Is Hiding a Troubling Trend for the Economy". Barron's. Archived from the original on June 4, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- Nedelman, Michael (May 17, 2018). "Why Americans are having fewer children". CNN. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- Edwards, Erika (November 27, 2019). "U.S. birth rate falls for 4th year in a row". Health News. NBC News. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- Weese, Karen (May 1, 2018). "Almost half of pregnancies in the U.S. are unplanned. There's a surprisingly easy way to change that". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- Cha, Ariana (April 28, 2016). "Teen birthrate hits all-time low, led by 50 percent decline among Hispanics and blacks". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- Patten, Eileen; Livingston, Gretchen (April 29, 2016). "Why is the teen birth rate falling?". Pew Research Center. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- Cha, Ariana (April 28, 2016). "Teen birthrate hits all-time low, led by 50 percent decline among Hispanics and blacks". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- "Too Much Netflix, Not Enough Chill: Why Young Americans Are Having Less Sex". Politico Magazine. February 8, 2018.

- Williams, Alex (November 20, 2021). "To Breed or Not to Breed?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- Kearney, Melissa S.; Levine, Phillip B. (January 9, 2022). "The Causes and Consequences of Declining US Fertility". Aspen Economic Strategy Group Policy Volume.

- Brown, Anna (November 19, 2021). "Growing share of childless adults in U.S. don't expect to ever have children". Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- Smith, Molly (August 31, 2022). "Women Who Stay Single and Don't Have Kids Are Getting Richer". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on August 31, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- Neal, Zachary P.; Neal, Jennifer Watling (July 25, 2022). "Prevalence, age of decision, and interpersonal warmth judgements of childfree adults". Scientific Reports. 12 (11907): 11907. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1211907N. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-15728-z. PMC 9314368. PMID 35879370. S2CID 251068886.

- Ward, Kim (July 25, 2022). "Study: One in five adults don't want children — and they're deciding early in life". MSU Today. Michigan State University. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- Bureau, US Census. "The Graying of America: More Older Adults Than Kids by 2035". The United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- Tileva, Toni. "Combating Age Bias in the Workplace." Alexandria, Virginia: Society for Human Resource Management, September 14, 2022.

- Nova, Annie. "How older workers can push back against the reality of ageism." CNBC, March 20, 2022.

- Gosselin, Peter and Ariana Tobin. "Cutting 'Old Heads' at IBM." ProPublica and Mother Jones, March 22, 2018.

- "Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060" (PDF).

- Howard, John (March 23, 2011), "The Future Workforce and Applied Ergonomics", 14th Annual Applied Ergonomics conference & Expo, Orlando, Florida

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schill, Anita L. (May 18, 2011), The Future of Work & the Aging Workforce, Electricity Safety Summit, Washington, District of Columbia

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Chosewood, L. Casey (July 19, 2012). "CDC – NIOSH Science Blog – Safer and Healthier at Any Age: Strategies for an Aging Workforce". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Silverstein, Michael (2008). "Meeting the challenges of an aging workforce". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 51 (4): 269–280. doi:10.1002/ajim.20569. PMID 18271000.

- Krupnick, Matt (August 29, 2017). "After decades of pushing bachelor's degrees, U.S. needs more tradespeople". PBS Newshour. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- Obando, Sebastian (July 9, 2021). "Median age of construction workers is contributing factor to workforce shortages". Construction Dive. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- Solman, Paul (January 28, 2021). "Despite rising salaries, the skilled-labor shortage is getting worse". PBS Newshour. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- Dizikes, Peter (September 15, 2021). "Study: As a population gets older, automation accelerates". MIT News. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- Acemoglu, Daron; Restrepo, Pascual (January 2022). "Demographics and Automation". The Review of Economic Studies. 89 (1): 1–44. doi:10.1093/restud/rdab031. hdl:1721.1/144423.

- Cohn, Scott (June 13, 2022). "Worker shortages, supply chain crisis fuel 2022 Top States for Business battle". CNBC. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- Rodriguez-Sanchez, Jose Ivan (September 5, 2022). "Legal work-related immigration has fallen by a third since 2020, contributing to US labor shortages". The Conversation. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- Nerkar, Santul (April 13, 2023). "Why An Aging Population Might Not Doom The American Economy". Five Thirty Eight. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- "Can Gen Z Save Manufacturing from the 'Silver Tsunami'?". Industry Week. July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- Zeihan, Peter (2022). "Section I: The End of More". The End of the World Is Just the Beginning: Mapping the Collapse of Globalization. New York: Harper Business. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-063-23047-7.

- Morgan, Kate (August 18, 2022). "Why workers just won't stop quitting". BBC Work Life. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- Fry, Richard (July 24, 2019). "Baby Boomers are staying in the labor force at rates not seen in generations for people their age". Pew Research Center. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- "Data and Statistics – Productive Aging and Work | NIOSH | CDC". www.cdc.gov. February 21, 2020. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- Graham-Harrison, Emma; McCurry, Justin (January 22, 2023). "Ageing planet: the new demographic timebomb". The Guardian. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- Sciubba, Jennifer D. (November 18, 2022). "The Global Population Is Aging. Is Your Business Prepared?". Harvard Business Review. Archived from the original on November 19, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- Fry, Richard (November 9, 2020). "The pace of Boomer retirements has accelerated in the past year". Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- Krupnick, Matt (August 29, 2017). "After decades of pushing bachelor's degrees, U.S. needs more tradespeople". PBS Newshour. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- Ferguson, Niall (October 23, 2022). "How Cold War II Could Turn Into World War III". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- Irwin, Niel (November 29, 2022). "How an aging population makes inflation worse". Axios. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- Stone, Lyman (February 11, 2021). "Escaping the Parent Trap". AEI. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- Murray, Stephanie H. (June 9, 2021). "How Low Can America's Birth Rate Go Before It's A Problem?". FiveThirtyEight. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- Manjoo, Farhad (May 20, 2021). "The World Might Be Running Low on Americans". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- Ermey, Ryan (October 25, 2022). "If you're not planning to have kids, you can rethink 'the whole foundation' of your financial plan". CNBC. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- Zeihan, Peter (2016). "Chapter 5: The End of the (Old) World". The Absent Superpower: The Shale Revolution and a World without America. Austin, TX: Zeihan on Geopolitics. ISBN 978-0-9985052-0-6.

- McHugh, Calder (June 11, 2019). "Morgan Stanley: Millennials, Gen Z set to boost the US economy". Yahoo Finance. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- Fuxian, Yi (March 10, 2023). "The Chinese century is already over". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- Woolley, Josephine (2006). Ageism in the Era of Workforce Shrinkage. Greenleaf Publishing (IngentaConnect). pp. 113–129. ISBN 978-1-909-49360-5.

- "America is building chip factories. Now to find the workers". The Economist. August 5, 2023. Archived from the original on August 5, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- Shalal, Andrea (July 12, 2021). "Aging population to hit U.S. economy like a 'ton of bricks' -U.S. commerce secretary". Reuters. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- Dee, Thomas (November 2, 2022). "Public School Enrollment Is Down by More Than a Million. Why?". Education Week. Archived from the original on November 28, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- Carey, Kevin (November 21, 2022). "The incredible shrinking future of college". Vox. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- Barshay, Jill (November 21, 2022). "PROOF POINTS: 861 colleges and 9,499 campuses have closed down since 2004". Hechinger Report. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- "Expert predicts 25% of colleges will "fail" in the next 20 years". CBS News. August 31, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- Marcus, Jon (April 18, 2023). "In Japan, plummeting university enrollment forecasts what's ahead for the U.S." Hechinger Report. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- Marcus, Jon (May 22, 2021). "Colleges face reckoning as plummeting birthrate worsens enrollment declines". Hechinger Report. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- Dutt-Ballerstadt, Reshmi (March 1, 2019). "Academic Prioritization or Killing the Liberal Arts?". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- "A look at trends in college and university consolidation since 2016". Education Dive. November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- Joshua, Kim (February 24, 2022). "'The Super Age' and Our Aging Higher Ed Workforce". Inside Higher Education. Archived from the original on April 9, 2023. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- Striessnig, Erich; Lutz, Wolfgang (August 1, 2013). "Can below-replacement fertility be desirable?". Empirica. 40 (3): 409–425. doi:10.1007/s10663-013-9213-3. ISSN 1573-6911. S2CID 154120884. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- Oliveira, Alexandra (June 4, 2021). "No, Henny-Penny, America's demographic sky is not falling". TheHill. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- "Birth rates are falling but overpopulation still a concern". June 12, 2012. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- Perkins, Sid (July 11, 2017). "The best way to reduce your carbon footprint is one the government isn't telling you about". Science. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- Davis, Adam (June 2019). "The Problem of Overpopulation: Proenvironmental Concerns and Behavior Predict Reproductive Attitudes". Environmentalism and Reproductive Attitudes. 11 (2): 92–100. doi:10.1089/eco.2018.0068. S2CID 149584136.

- Shead, Sam (August 12, 2021). "Climate change is making people think twice about having children". CNBC. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- Smith, Noah (February 11, 2021). "Everyone Has to Pay When America Gets Too Old". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on June 4, 2022.

- Hasnan, Liyana (August 15, 2019). "No more babies for ASEAN?". ASEAN Post. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- Haas, Mark L. (April 2, 2020). "War-Weary America's Little-Known Deterrent: Its Aging Population". National Interest. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- "China's median age will soon overtake America's". The Economist. October 31, 2019. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- "For the first time since the 1960s, China's population is shrinking". The Economist. January 17, 2023. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- Ferguson, Niall (August 14, 2022). "China's Demographics Spell Decline Not Domination". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- Cox, Simon (November 18, 2022). "Will China's economy ever overtake America's in size?". The Economist. Archived from the original on November 19, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- French, Howard (July 29, 2022). "A Shrinking China Can't Overtake America". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on August 23, 2022. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- Xie, Stella Yifan (September 2, 2022). "China's Economy Won't Overtake the U.S., Some Now Predict". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 9, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- Moritsugu, Ken (January 18, 2022). "Threats, advantages seen in China's shrinking population". Associated Press. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- Brands, Hal; Beckley, Michael (September 24, 2021). "China Is a Declining Power—and That's the Problem". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- Grosch, James W.; Pransky, Glenn S. (2010), "Safety and Health Issues for an Aging Workforce", in Czaja, Sara J.; Sharit, Joseph (eds.), Aging and Work: Issues and Implications in a Changing Landscape, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press

- Caban-Martinez, Alberto J.; Lee, David J.; Fleming, Lora E.; Tancredi, Daniel J.; Arheart, Kristopher L.; LeBlanc, William G.; McCollister, Kathryn E.; Christ, Sharon L.; Louie, Grant H.; Muennig, Peter A. (2011), "Arthritis, occupational class, and the aging US workforce", American Journal of Public Health, 101 (9): 1729–1734, doi:10.2105/ajph.2011.300173, PMC 3154222, PMID 21778483

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011), "Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses among older workers – United States, 2009", Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60 (16): 503–508, PMID 21527887

- Versace, Chris; Abssy, Mark (February 4, 2022). "Investing in an Aging Population Amid a Structural Shift in Demographics". NASDAQ. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- Schwatka, Natalie V.; Butler, Lesley M.; Rosecrance, John R. (2012), "An aging workforce and injury in the construction industry", Epidemiologic Reviews, 34: 156–167, doi:10.1093/epirev/mxr020, PMC 7735369, PMID 22173940

- Fry, Richard (July 24, 2019). "Baby Boomers are staying in the labor force at rates not seen in generations for people their age". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- "America faces a debt nightmare". The Economist. May 3, 2023. Archived from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- Dong, Xiuwen S.; Wang, Xuanwen; Daw, Christina; Ringen, Knut (2011), "Chronic disease and functional limitations among older construction workers in the United States: a 10-year follow-up study", Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53 (4): 372–380, doi:10.1097/jom.0b013e3182122286, PMID 21407096, S2CID 13763613

- Bob Shepard, The University of Alabama at Birmingham (December 30, 2010). "Beware the "silver tsunami" – the boomers turn 65 in 2011". The University of Alabama at Birmingham. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Boak, Josh; Seitz, Amanda (February 20, 2023). "Social Security and Medicare: Troubling math, tough politics". Associated Press. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- Goldstein, Dana; Gebeloff, Robert (December 1, 2022). "As Gen X and Boomers Age, They Confront Living Alone". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- The Economist (February 4, 2010). "Schumpeter: The silver tsunami". The Economist. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Levy, Becca (August 10, 2022). "How America's ageism hurts, shortens lives of elderly". Health and Medicine. Harvard Gazette. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- Chamie, Joseph (May 20, 2021). "2024: The Historic Reversal of America's population". The Hill. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- Turchin, Peter (2013). "Modeling Social Pressures Toward Political Instability". Cliodynamics. 4 (2). doi:10.21237/C7clio4221333.

- Venhuizen, Harm (May 25, 2023). "Kids could fill labor shortages, even in bars, if these lawmakers succeed". Associated Press. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- Ory, Marcia G. (September 25, 2020). "How Will Society Change As The U.S. Population Ages?". The Conversation. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- Meola, Andrew. "The aging US population is creating many problems—especially regarding elderly healthcare issues". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- Pinsker, Joe (July 6, 2021). "The 2 Ways to Raise a Country's Birth Rate". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 8, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- Lopez, Rachel (February 29, 2020). "Baby monitor: See how family size is shrinking". Hindustan Times. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Sin, Yuen (March 2, 2018). "Govt aid alone not enough to raise birth rate: Minister". Singapore. Straits Times. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- Sui, Cindy (August 15, 2011). "Taiwanese birth rate plummets despite measures". Asia-Pacific. BBC News. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- McCurry, Justin; Rashid, Raphael (November 19, 2022). "I'm afraid to have children': fear of an older future in Japan and South Korea". The Guardian. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- Raftery, Adrian (June 21, 2021). "The dip in the US birthrate isn't a crisis, but the fall in immigration may be". The Conversation. Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- Feffer •, John (May 7, 2021). "Immigration Is the Solution for the Falling US Birth Rate". Fair Observer. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- MacNamara, Trent (March 26, 2019). "Liberal Societies Have Dangerously Low Birth Rates". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- Khazan, Olga (May 26, 2018). "A Surprising Reason to Worry About Low Birth Rates". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- Stone, Lyman (November 10, 2017). "The US needs more babies, more immigrants, and more integration". Vox. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- "Can Better Policies Solve the West's Population Crisis?". Time. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- "Two new books explain the Brexit revolt". Britain. The Economist. November 3, 2018. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Jonas, Michael (August 5, 2007). "The downside of diversity". Americas. The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- Saad, Lydia (August 8, 2022). "U.S. Immigration Views Remain Mixed and Highly Partisan". Gallup. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- Kim, Tae (July 20, 2023). "The Chip Act's Big Problem". Barron's. Archived from the original on July 20, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

Further reading

- Wells, Robert V. (1971). "Family Size and Fertility Control in Eighteenth-Century America: A Study of Quaker Families". Population Studies. Taylor & Francis. 25 (1): 73–82. doi:10.2307/2172749. JSTOR 2172749. PMID 11630442.

- Haines, Michael R. (1994). "The Population of the United States, 1790–1920" (PDF). Historical Working Paper (56). National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/h0056. S2CID 129876349. SSRN 190393. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Purvis, Thomas L. (1995). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Revolutionary America 1763 to 1800. New York: Facts on File. pp. 123–183. ISBN 978-0816025282.

- Shifflett, Crandall (1996). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Victorian America 1876 to 1913. New York: Facts on File. pp. 73–83. ISBN 978-0816025312.

- Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763. New York: Facts on File. pp. 128–167. ISBN 978-0816025275.

- Selcer, Richard F. (2006). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Civil War America 1850 to 1875. New York: Facts on File. pp. 114–141. ISBN 978-0816038671.

- Bailey, Martha; Hershbein, Brad J. (2015). "U.S. Fertility Rates and Childbearing, 1800 to 2010" (PDF). University of Michigan. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Cain, Louis P.; Fishback, Price V.; Rhode, Paul W., eds. (2018). The Oxford Handbook of American Economic History, Volume 1. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190882617.