Esing Bakery incident

The Esing Bakery incident,[n 1] also known as the Ah Lum affair, was a food contamination scandal in the early history of British Hong Kong. On 15 January 1857, during the Second Opium War, several hundred European residents were poisoned non-lethally by arsenic, found in bread produced by a Chinese-owned store, the Esing Bakery. The proprietor of the bakery, Cheong Ah-lum,[n 2] was accused of plotting the poisoning but was acquitted in a trial by jury. Nonetheless, Cheong was successfully sued for damages and was banished from the colony. The true responsibility for the incident and its intention—whether it was an individual act of terrorism, commercial sabotage, a war crime orchestrated by the Qing government, or purely accidental—both remain a matter of debate.

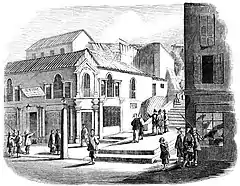

Esing Bakery, from The Illustrated London News (1857) | |

| Date | 15 January 1857 |

|---|---|

| Location | Victoria, British Hong Kong |

| Cause | Arsenic poisoning |

| Casualties | |

| 300–500 taken ill, predominantly Europeans | |

| Deaths | 0 at the time of the event, 3 from long-term consequences |

| Arrests | 57 Chinese men |

| Accused | Cheong Ah-lum and 9 others |

| Charges | "Administering poison with intent to kill and murder"[1] |

| Verdict | Not guilty |

| Esing Bakery incident | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 裕成辦館毒麵包案 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 裕成办馆毒面包案 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Esing Bakery poisoned bread case | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

In Britain, the incident became a political issue during the 1857 general election, helping to mobilise support for the war and the incumbent Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston. In Hong Kong, it sowed panic and insecurity among the local colonists, highlighting the precariousness of imperial rule in the colony. The incident contributed to growing tensions between Hong Kong's European and Chinese residents, as well as within the European community itself. The scale and potential consequences of the poisoning make it an unprecedented event in the history of the British Empire, the colonists believing at the time that its success could have wiped out their community.

Background

In 1841, in the midst of the First Opium War, Captain Charles Elliot negotiated the cession of Hong Kong by the Qing dynasty of China to the British Empire in the Convention of Chuenpi.[2] The colony's early administrators held high hopes for Hong Kong as a gateway for British influence in China as a whole, which would combine British good government with an influx from China of what were referred to at the time as "intelligent and readily improvable artisans", as well as facilitating the transfer of coolies to the West Indies.[3] However, the colonial government soon found it difficult to govern Hong Kong's rapidly expanding Chinese population,[4][5] and was also faced with endemic piracy[6] and continued hostility from the Qing government.[7][8] In 1856, the Governor of Hong Kong, John Bowring, supported by the British Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, demanded reparations from the Qing government for the seizure of a Hong Kong Chinese-owned ship, which led to the Second Opium War between Britain and China (1856–1860).[9]

At the opening of the war in late 1856, Qing imperial commissioner Ye Mingchen unleashed a campaign of terrorism in Hong Kong by a series of proclamations offering rewards for the deaths of what he called the French and British "rebel barbarians", and ordering Chinese to renounce employment by the "foreign dogs".[10] A committee to organise resistance to the Europeans was established at Xin'an County on the mainland.[11] At the same time, Europeans in Hong Kong became concerned that the turmoil in China caused by the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) was producing a surge of Chinese criminals into the colony.[9] Tensions between Chinese and European residents ran high, and in December 1856 and January 1857 the Hong Kong government enacted emergency legislation, imposing a curfew on Hong Kong Chinese and giving the police sweeping powers to arrest and deport Chinese criminals and to resort to lethal force at night-time. Well-off Chinese residents became increasingly disquieted by the escalating police brutality and the level of regulation of Chinese life.[12]

Course of events

.jpg.webp)

On 15 January 1857, between 300 and 500 predominantly European residents of the colony—a large proportion of the European population at the time—who had consumed loaves from the Esing Bakery (Chinese: 裕成辦館; Cantonese Yale: Yuhsìhng baahngún[13]) fell ill with nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, and dizziness. Later testing concluded that the bread had been adulterated with large amounts of arsenic trioxide.[14] The quantity of arsenic involved was high enough to cause the poison to be vomited out before it could kill its victims.[15] There were no deaths immediately attributable to the poisoning,[16] though three deaths that occurred the following year, including that of the wife of Governor Bowring, would be ascribed to its long-term effects.[15] The colony's doctors, led by Surgeon General Aurelius Harland, dispatched messages across the town advising that the bread was poisoned and containing instructions to induce vomiting and consume raw eggs.[17]

The proprietor of the bakery, Cheong Ah-lum (Chinese: 張霈霖; Cantonese Yale: Jēung Puilàhm[13]), left for Macau with his family early in the day.[18] He was immediately suspected of being the perpetrator, and as news of the incident rapidly spread, he was detained there and brought back to Hong Kong the next day. By the end of the day, 52 Chinese men had been rounded up and detained in connection to the incident.[14] Many of the local Europeans, including the Attorney General, Thomas Chisholm Anstey, wished Cheong to be court-martialled[19]—some called for him to be lynched.[20] Governor Bowring insisted that he be tried by jury.[19]

On 19 January ten of the men[n 3] were committed to be tried at the Supreme Court after a preliminary examination. This took place on 21 January. The other detainees were taken to Cross Roads police station and confined in a small cell, which became known as the 'Black Hole of Hong Kong' after the Black Hole of Calcutta.[18] Some were deported several days later,[14] while the rest remained in the Black Hole for nearly three weeks.[21]

Supreme Court trial

The trial opened on 2 February.[1] The government had difficulty selecting appropriate charges because there was no precedent in English criminal law for dealing with the attempted murder of a whole community.[22] One of the victims of the poisoning was selected, and Cheong and the nine other defendants were charged with "administering poison with intent to kill and murder James Carroll Dempster, Colonial Surgeon".[1] Attorney General Anstey led the prosecution, William Thomas Bridges and John Day the defence.[23] Chief Justice John Walter Hulme, who had himself been poisoned, presided.[24]

The arguments at the trial focused more on Cheong's personal character than on the poisoning itself: the defence argued that Cheong was a highly regarded and prosperous member of the local community with little reason to take part in an amateurish poisoning plot, and suggested that Cheong had been framed by his commercial competitors. The prosecution, on the other hand, painted him as an agent of the Qing government, ideally positioned to sabotage the colony. They claimed he was financially desperate and had sold himself out to Chinese officials in return for money.[25]

The defence noted that Cheong's own children had shown symptoms of poisoning; Attorney General Anstey argued that they had merely been seasick,[26] and added that even if Cheong were innocent, it was "better to hang the wrong man than confess that British sagacity and activity have failed to discover the real criminals".[27] Hulme retorted that "hanging the wrong man will not further the ends of justice".[18] Cheong himself called for his own beheading, along with the rest of his family, if he were found guilty, in accordance with Chinese practice.[28] On 6 February, the jury rejected the arguments of the prosecution and returned a 5–1 verdict of 'not guilty'.[1]

Banishment of Cheong

The verdict triggered a sensation, and despite his acquittal, public opinion among the European residents of Hong Kong remained extremely hostile to Cheong. Governor Bowring and his Executive Council had determined while the trial was still underway that Cheong should be detained indefinitely regardless of its outcome,[29] and he was arrested soon afterwards under emergency legislation on the pretext of being what the authorities called a "suspicious character". William Tarrant, the editor of the Friend of China, sued Cheong for damages. He was awarded $1,010.[30][n 4] Before the sentence could be executed, Bridges, now Acting Colonial Secretary, accepted a petition from the Chinese community for Cheong to be allowed to leave peaceably from Hong Kong after putting his affairs in order. Cheong was accordingly released and left the colony on 1 August, abandoning his business.[29]

Tarrant blamed Bridges publicly for permitting Cheong to escape, but was himself consequently sued for libel by Bridges and forced to pay a fine of £100.[31][n 4]

Analysis

Responsibility

Modern scholars have been divided in attributing the responsibility for the incident. The historian George Beer Endacott argued that the poisoning was carried out on the instruction of Qing officials, while Jan Morris depicts Cheong as a lone wolf acting out of personal patriotism. Cheong's own clan record, written in China in 1904 at the command of the imperial court, states that the incident was entirely accidental, the result of negligence in preparing the bread rather than intentional poisoning. Yet another account says that the poisoning was carried out by two foremen at the bakery who fled Hong Kong immediately afterwards, and Cheong was uninvolved.[24] Lowe and McLaughlin, in their 2015 investigation of the incident, classify the plausible hypotheses into three categories: that the poisoning was carried out by Cheong or an employee on orders from Chinese officials; that the poisoning was an attempt by a rival to frame Cheong; and that the poisoning was accidental.[32]

Lowe and McLaughlin state that the chemical analyses conducted at the time do not support the theory that the incident was accidental. Cheong's clan record reports that "one day, through carelessness, a worker dropped some 'odd things' into the flour", even though the arsenic was found only in the bread itself, and in massive quantities—not in the flour, yeast, pastry, or in scrapings collected from the table, all of which were tested. If these results are correct, the poison must have been introduced shortly before baking.[15] Moreover, despite its ultimate failure, Lowe and McLaughlin argue that the incident had certain characteristics of careful strategic planning: the decision to poison European-style bread, a food generally not eaten by Chinese at the time, would have served to separate the intended targets of the plot, while white arsenic (arsenic trioxide) was a fast-acting poison naturally available in China, and so well-suited to the task.[17]

In June 1857, the Hong Kong Government Gazette published a confiscated letter written to Chan Kwei-tsih, the head of the resistance committee in Xin'an County, from his brother Tsz-tin, informing him of the incident. The second-hand report in the missive suggests that the committee was unlikely to have instigated the incident directly.[33]

Toxicology

Aurelius Harland, the Surgeon General, conducted the initial tests on the bread and other materials recovered from the bakery. He recorded:

Soon after the first alarm, I endeavoured to ascertain in a hasty way what was in the bread, and Dr Bradford coming in, he and I satisfied ourselves that it was arsenic. Next day, at the request of the Colonial Secretary, we made a more careful analysis of each piece of bread separately, and found they all indicated the presence of arsenic. ... we found that one pound [0.45 kg] loaf of bread contained nearly a drachm of arsenic, sixty grains to the drachm, common white arsenic. ... I also, on the afternoon of the 16th, had two jars brought me by a policeman, one containing yeast used on the night of the 14th, the other the materials for making yeast, together with some flour and some pastry from the bakery, paste scraped from the table, and some pastry in tin moulds. I found no trace of arsenic or other metallic poison in any of the materials.[34][n 5]

Portions of the poisoned bread were subsequently sealed and dispatched to Europe, where they were examined by the chemists Frederick Abel[15] and Justus von Liebig, and the Scottish surgeon John Ivor Murray.[35] Murray found the incident to be scientifically interesting because of the low number of deaths that resulted from the ingestion of such a massive quantity of arsenic. Chemical tests enabled him to obtain 62.3 grains of arsenous acid per pound of bread (9 parts per thousand), while Liebig found 64 grains/lb (10 parts per thousand).[35] Liebig theorised that the poison had failed to act because it was vomited out before digestion could take place.[35]

Effects and aftermath

Reception in Britain

News of the incident reached Britain during the 1857 general election,[36] which had been called following a successful parliamentary vote of censure of Lord Palmerston's support for the Second Opium War.[37] Mustering support for Palmerston and his war policy, the London Morning Post decried the poisoning in hyperbolic terms, describing it as a "hideous villainy, [an] unparalleled treachery, of these monsters of China", "defeated ... by its very excess of iniquity"; its perpetrators were "noxious animals ... wild beasts in human shape, without one single redeeming value" and "demons in human shape".[36] Another newspaper supportive of Palmerston, the Globe, published a fabricated letter by Cheong admitting that he "had acted agreeably to the order of the Viceroy [Ye Mingchen]".[38] By the time the news of Cheong's acquittal was published in London on 11 April, the election was all but over, and Palmerston was victorious.[39]

In London, the incident came to the attention of the German author Friedrich Engels, who wrote to the New York Herald Tribune on 22 May 1857, saying that the Chinese now "poison the bread of the European community at Hong Kong by wholesale, and with the coolest premeditation". "In short, instead of moralizing on the horrible atrocities of the Chinese", he argued, "as the chivalrous English press does, we had better recognize that this is a war pro aris et focis, a popular war for the maintenance of Chinese nationality, with all its overbearing prejudice, stupidity, learned ignorance and pedantic barbarism if you like, but yet a popular war."[40]

Others in England denied that the poisoning had even happened. In the House of Commons, Thomas Perronet Thompson alleged that the incident had been fabricated as part of a campaign of disinformation justifying the Second Opium War.[41] Much of the disbelief centred on Cheong's name, which became an object of sarcasm and humour—bakers in 19th-century Britain often adulterated their dough with potassium alum, or simply 'alum', as a whitener[42] —and Lowe and McLaughlin note that "a baker named Cheong Alum would have been considered funny by itself, but a baker named Cheong Alum accused of adding poison to his own dough seemed too good to be true". An official of the Colonial Office annotated a report on Cheong from Hong Kong with the remark, "Surely a mythical name".[43]

Hong Kong

Both the scale of the poisoning and its potential consequences make the Esing bakery incident unprecedented in the history of the British Empire,[44] with the colonists believing at the time that its success could have destroyed their community.[18]

Morris describes the incident as "a dramatic realization of that favourite Victorian chiller, the Yellow Peril",[45] and the affair contributed to the tensions between the European and Chinese communities in Hong Kong. In a state of panic,[46] the colonial government conducted mass arrests and deportations of Chinese residents in the wake of the poisonings.[47] 100 new police officers were hired and a merchant ship was commissioned to patrol the waters surrounding Hong Kong. Governor Bowring wrote to London requesting the dispatch of 5,000 soldiers to Hong Kong.[46] A proclamation was issued reaffirming the curfew on Chinese residents, and Chinese ships were ordered to be kept beyond 300 yards (270 m) of Hong Kong, by force if necessary.[48] Chan Tsz-tin described the aftermath in his letter:

... the English barbarians are in very great perplexity; that a proclamation is issued every day, and three sets of regulations come out in two days. People out at night are taken up in a haste, and let go in a hurry; no one is allowed out after 8 o'clock; the shops are forced to take out tickets at sixteen dollars each.[49]

The Esing Bakery was closed, and the supply of bread to the colonial community was taken over by the English entrepreneur George Duddell,[50] described by the historian Nigel Cameron as "one of the colony's most devious crooks".[51] Duddell's warehouse was attacked in an arson incident on 6 March 1857, indicative of the continuing problems in the colony.[50] In the same month, one of Duddell's employees was reported to have discussed being offered $2,000 to adulterate biscuit dough with a soporific—the truth of this allegation is unknown.[22] Soon after the poisoning, Hong Kong was rocked by the Caldwell affair, a series of scandals and controversies involving Bridges, Tarrant, Anstey, and other members of the administration, similarly focused on race relations in the colony.[52]

Cheong himself made a prosperous living in Macau and Vietnam after his departure from Hong Kong, and later became consul for the Qing Empire in Vietnam. He died in 1900.[24] A portion of the poisoned bread, well-preserved by its high arsenic content, was kept in a cabinet of the office of the Chief Justice of the Hong Kong Supreme Court until the 1930s.[45]

Notes

- Also spelled ESing, E-sing, or E Sing.

- Also spelled A(-)lum, Allum, Ahlum, or Ah Lum instead of Ah-lum, or Cheung instead of Cheong.

- Murray lists the ten men as Cheong A-lum, Cheong Achew, Cheong Aheep, Cheong Achok, Lum Asow, Tam Aleen, Fong Angee, Cheong Amun, Fong Achut, and Cheong Wye Kong: Murray 1858, p. 13.

- Multiple currencies were in circulation in early British Hong Kong, including Mexican or Spanish dollars as well as the pound sterling: Munn 2009, p. xiv.

- A drachm is a small weight, equal to one eighth of one troy ounce (31 g), or about 3.9 grams. A grain is the smallest unit of weight, with 7000 grains in one pound (0.45 kg). A drachm of arsenic in this sized loaf of bread is therefore equivalent to 9 parts per thousand.

References

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, p. 191.

- Carroll 2007, p. 12.

- Munn 2009, pp. 39, 38.

- Carroll 2007, p. 48.

- Tsai 2015, pp. 12–3.

- Carroll 2007, p. 19.

- Munn 2009, p. 57.

- Carroll 2007, p. 21.

- Tsai 2015, p. 13.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, p. 192.

- Munn 2009, p. 278.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, pp. 193–4.

- 湯, 開建 (2018). 陳, 超敏 (ed.). 清代香山鐵城張氏家族與澳門的關係──以《曲江張氏族譜香山鐵城宗支譜》為中心展開 (PDF). 澳門研究. 澳門基金會 (88): 121, 123. ISSN 0872-8526.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, p. 190.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, p. 197.

- Pope-Hennessy 1969, p. 57.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, p. 196

- Carroll 2007, p. 26.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, pp. 190–191.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, p. 200

- Pope-Hennessy 1969, p. 58.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, p. 198.

- Norton-Kyshe 1898, p. 416

- Schoonakker 2007.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, pp. 199–200.

- Bowman 2016, p. 307.

- Ingham 2007, p. 64.

- Bowman 2016, pp. 307–8.

- Munn 2009, p. 283.

- Cho 2017, p. 282.

- Cameron 1991, p. 83.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, p. 194.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, pp. 197–8.

- Murray 1858, p. 14.

- Murray 1858, p. 16.

- Wong 1998, pp. 226–7.

- Fenton 2012, p. 140.

- Wong 1998, p. 227.

- Wong 1998, pp. 227–8.

- Engels 1857.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, pp. 202–3.

- Dunnigan 2003, p. 341.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, p. 201.

- Lowe & McLaughlin 2015, p. 189.

- Morris 2007, p. 52.

- Cho 2017, p. 280.

- Cho 2017, p. 279.

- Munn 2009, p. 284.

- Munn 2009, p. 257.

- Munn 2009, p. 276.

- Cameron 1991, p. 83

- Ingham 2007, p. 65.

Sources

- Bowman, Marilyn Laura (2016). James Legge and the Chinese Classics: A Brilliant Scot in the Turmoil of Colonial Hong Kong. Victoria: FriesenPress. ISBN 9781460288849.

- Cameron, Nigel (1991). An Illustrated History of Hong Kong. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195849973. (registration required)

- Carroll, John Mark (2007). A Concise History of Hong Kong. Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742534223.

- Cho, Lily (2017). "Sweet and Sour: Historic Presence and Diasporic Agency". In Coloma, Ronald Sintos; Pon, Gordon (eds.). Asian Canadian Studies Reader. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 279–98. ISBN 978-1442630284. (password-protected)

- Dunnigan, M. (2003). "Commentary: John Snow and alum-induced rickets from adulterated London bread: an overlooked contribution to metabolic bone disease" (PDF). International Journal of Epidemiology. 32 (3): 340–41. doi:10.1093/ije/dyg160. PMID 12777415.

- Engels, Friedrich (22 May 1857). "Persia — China". New York Herald Tribune. Marxists Internet Archive.

- Fenton, Laurence (2012). Palmerston and The Times: Foreign Policy, the Press and Public Opinion in Mid-Victorian Britain. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781780760742.

- Ingham, Michael (2007). Hong Kong: A Cultural History. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195314977.

- Lowe, Kate; McLaughlin, Eugene (2015). "'Caution! The bread is poisoned': The Hong Kong mass poisoning of January 1857" (PDF). The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 43 (2): 189–209. doi:10.1080/03086534.2014.974904. S2CID 159790706. (open-access preprint)

- Morris, Jan (2007) [1988]. Hong Kong: Epilogue to an Empire (2nd ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0141001296.

- Munn, Christopher (2009). Anglo-China: Chinese People and British Rule in Hong Kong, 1841–1880 (2nd ed.). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789622099517.

- Murray, J. Ivor (1858). "Note of the Result of an Analysis of a Portion of the Bread with which A-lum was accused of Poisoning the European Residents at Hong-Kong". Edinburgh Medical Journal. 4 (1): 13–16. PMC 5309086. PMID 29646651.

- Norton-Kyshe, James William (1898). The History of the Laws and Courts of Hongkong. Vol. 1. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Pope-Hennessy, James (1969). Half-Crown Colony: A Hong Kong Notebook. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Schoonakker, Bonny (15 January 2007). "Racial tensions mixed with a dash of arsenic and yeast". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Simpson, John A.; Weiner, Edmund S.C., eds. (1989). "Home : Oxford English Dictionary". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8. OCLC 50959346.

- Tsai, Jung-fang (2015) [1999]. "From Antiforeignism to Popular Nationalism: Hong Kong between China and Britain, 1839–1911". In Chan, Ming K. (ed.). Precarious Balance: Hong Kong Between China and Britain, 1842–1992. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 9–26. ISBN 9781563243813.

- Wong, J. Y. (1998). Deadly Dreams: Opium and the Arrow War (1856–1860) in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521552559.