Anbar campaign (2003–2011)

The Anbar campaign consisted of fighting between the United States military, together with Iraqi security forces, and Sunni insurgents in the western Iraqi governorate of Al Anbar. The Iraq War lasted from 2003 to 2011, but the majority of the fighting and counterinsurgency campaign in Anbar took place between April 2004 and September 2007. Although the fighting initially featured heavy urban warfare primarily between insurgents and U.S. Marines, insurgents in later years focused on ambushing the American and Iraqi security forces with improvised explosive devices (IEDs), large scale attacks on combat outposts, and car bombings. Almost 9,000 Iraqis and 1,335 Americans were killed in the campaign, many in the Euphrates River Valley and the Sunni Triangle around the cities of Fallujah and Ramadi.[4]

| Anbar Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Iraq War | |||||||

U.S. Marines from 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines patrol through the town of Haqlaniyah, Al Anbar Governorate, in May 2006. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

List

|

Iraqi Insurgency List

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

47,000 Army and Police (September 2008)[2] |

Iraqi Insurgency Unknown[Note 1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

8,205+ wounded [4][5] |

1,702+ killed | ||||||

|

Iraqi civilians: unknown | |||||||

Al Anbar, the only Sunni-dominated province in Iraq, saw little fighting in the initial invasion. Following the fall of Baghdad it was occupied by the U.S. Army's 82nd Airborne Division. Violence began on 28 April 2003 when 17 Iraqis were killed in Fallujah by U.S. soldiers during an anti-American demonstration. In early 2004 the U.S. Army relinquished command of the governorate to the Marines. By April 2004 the governorate was in full-scale revolt. Savage fighting occurred in both Fallujah and Ramadi by the end of 2004, including the Second Battle of Fallujah. Violence escalated throughout 2005 and 2006 as the two sides struggled to secure the Western Euphrates River Valley. During this time, Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) became the governorate's main Sunni insurgent group and turned the provincial capital of Ramadi into its stronghold. The Marine Corps issued an intelligence report in late 2006 declaring that the governorate would be lost without a significant additional commitment of troops.

In August 2006, several tribes located in Ramadi and led by Sheikh Abdul Sattar Abu Risha began to form what would eventually become the Anbar Awakening, which later led to the tribes revolting against AQI. The Anbar Awakening helped turn the tide against the insurgents through 2007. American and Iraqi tribal forces regained control of Ramadi in early 2007, as well as other cities such as Hīt, Haditha, and Rutbah. More hard fighting still followed throughout the Summer of 2007 however, particularly in the rural western River Valley, due largely to its proximity to the Syrian border and the vast network of natural entry points for foreign fighters to enter Iraq, via Syria. In June 2007 the U.S. turned a majority of its attention to eastern Anbar Governorate and secured the cities of Fallujah and Al-Karmah.

The fighting was mostly over by September 2007, although US forces maintained a stabilizing and advisory role through December 2011. Celebrating the victory, President George W. Bush flew to Anbar in September 2007 to congratulate Sheikh Sattar and other leading tribal figures. AQI assassinated Sattar days later. In September 2008, political control was transferred to Iraq. Military control was transferred in June 2009, following the withdrawal of American combat forces from the cities. The Marines were replaced by the US Army in January 2010. The Army withdrew its combat units by August 2010, leaving only advisory and support units. The last American forces left the governorate on 7 December 2011.

Background

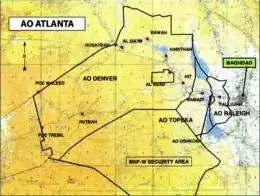

Al Anbar is Iraq's largest and westernmost governorate. It comprises 32 percent of the country's total land mass, nearly 53,208 square miles (137,810 km2), almost exactly the size of North Carolina in the United States and slightly larger than Greece. Geographically, it is isolated from most of Iraq, but is easy to access from Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Syria. The Euphrates River, Lake Habbaniyah, and the artificially created Lake Qadisiyah are its most significant geographical features. Outside of the Euphrates area the terrain is overwhelmingly desert, comprising the eastern part of the Syrian Desert. Temperatures range from highs of 115 °F (46 °C) in July and August to below 50 °F (10 °C) from November to March. The governorate lacks significant natural resources and many inhabitants benefited from the Ba'athist government's patronage system, funded by oil revenues from elsewhere in the country.[8]

The Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) estimated that about 1.2 million Iraqis lived in Anbar in 2003, more than two-thirds of them in Fallujah and Ramadi.[9] With a population 95 percent Sunni, many from the Dulaimi Tribe, Anbar is Iraq's only governorate without a significant Shia or Kurdish population. 95 percent of the population lives within 5 miles (8.0 km) of the Euphrates. At the time of the invasion, Fallujah was known as a religious enclave hostile towards outsiders, while Ramadi, the provincial capital, was more secular. Outside the cities, the ancient tribal system run by Sheikhs held considerable influence.[10]

Conditions in Anbar particularly favored an insurgency. The province was overwhelmingly Sunni, the minority religious group that lost its power and influence in post-Saddam Hussein Iraq. Hussein was also very popular in the province more than anywhere else in the country.[11] Many did not fight during the invasion (allowing them to claim that they had not been defeated) and "still wanted to slug it out", according to journalist Tom Ricks.[12] Military service was compulsory in Saddam's Iraq and the Amiriyah area contained a sizeable portion of Iraq's arms industry.[13][14] Immediately after Saddam fell, insurgents and others looted many of the 96 known munitions sites, as well as local armories and weapons stockpiles. These weapons were used to arm the insurgents in Anbar and elsewhere.[13] While only a small minority of Sunnis were initially insurgents, many either supported or tolerated them.[15] Sympathetic Ba'athists and former Saddam officials in Syrian exile provided money, sanctuary, and foreign fighters to insurgent groups. Future al-Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi spent part of 2002 in central Iraq, including Anbar Governorate, preparing for resistance.[16] Within several months of the invasion, the governorate had become a sanctuary for anti-occupation fighters.[14]

2003

Invasion

Anbar experienced relatively little fighting during the initial invasion of Iraq, as the main US offensive was directed through the Shia areas of southeastern Iraq, from Kuwait to Baghdad. An infantry division had been earmarked in 2002 to secure Anbar during the invasion. However, the Pentagon decided to treat the province with an "economy of force" in early 2003.[17] The first Coalition forces to enter Al Anbar were American and Australian special forces, who seized vital targets such as Al Asad Airbase and Haditha Dam and prevented the launch of Scud missiles at Israel.[18][19] While there was generally little combat, the most significant engagement occurred when elements of the American 3rd Battalion 75th Ranger Regiment seized Haditha Dam on 31 March 2003. Surrounded by a larger Iraqi force, the Rangers held the dam until relieved after eight days. During the siege, they destroyed twenty-nine Iraqi tanks and killed an estimated 300 to 400 Iraqi soldiers. Three Rangers were awarded the Silver Star for the action.[20][21] In addition, four other Rangers were killed when their checkpoint near Haditha was attacked by a suicide bomber.[22]

At the end of the invasion, the pro-Saddam forces in Anbar–the Ba'ath Party, the Republican Guard, the Fedayeen Saddam, and the Iraqi Intelligence Service—remained intact.[14] Saddam hid in Ramadi and Hīt in early April.[23] Other pro-Saddam forces were able to relocate from Anbar to Syria with money and weapons, where they set up headquarters. The nucleus of the insurgency in its first few months was formed from the pro-Saddam forces in Anbar and Syria. In contrast to the looting throughout Baghdad and other parts of the country, Ba'athist headquarters and homes of high-ranking Sunni leaders were relatively untouched.[24] The head of Iraqi ground forces in the province, General Mohammed Jarawi, formally surrendered to elements of the 3rd Infantry Division at Ramadi on 15 April 2003.[25]

Insurgency begins

We are not fighting for Saddam. We are fighting for our country, for our honor, for Islam. We are not doing this for Saddam.

— Religious student in Fallujah[26]

Shortly after the Fall of Baghdad, the US Army turned Anbar Governorate over to a single regiment, the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR). With only several thousand soldiers, that force had little hope of effectively controlling Anbar.[27]

The immediate catalyst for violent activity in the Fallujah area came after what many Iraqis and foreign journalists dubbed a "massacre" in Fallujah.[28][29] On the evening of 28 April 2003, Saddam Hussein's birthday, a crowd of about one hundred men, women, and children staged anti-American protests outside a US military outpost in Fallujah. The Iraqis claimed they were unarmed,[30] while the Army said that some individuals were carrying and firing AK-47s. The 82nd Airborne soldiers manning the schoolhouse outpost fired on the crowd, killing at least twelve and wounding dozens more.[31] The Army never apologized for the killings or paid compensation.[32] In the weeks afterwards, the town's pro-US mayor urged the Americans to leave.[33]

On 16 May 2003, the CPA issued Order Number 1, which abolished the Ba'ath Party and began a process of "de-Ba'athification", and on 23 May 2003 issued Order Number 2, which disbanded the Iraqi Army and other security services. Both orders further antagonized the Sunnis of Anbar.[34] Many Sunnis took great pride in the Iraqi Army and viewed its disbanding as an act of contempt towards the Iraqi people.[32] The dissolution also put hundreds of thousands of Anbaris out of work as many were members of the Army or the party.[35] Three days after CPA Order No. 2, Major Matthew Schram became the first American killed since the invasion in Anbar Governorate when his convoy came under rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) attack on 26 May near Haditha.[4][36]

June–October 2003

What we have done over the last six months in Al Anbar has been a recipe for instability.

— CPA Diplomat Keith Mines, November 2003[37]

Following the disbanding of the Iraqi Army, insurgent activity increased, especially in Fallujah. Initially, armed resistance groups could be characterized as either Sunni nationalists who wanted to bring back the Ba'ath Party with Saddam Hussein, or anti-Saddam fighters.[35] The first major leader of the insurgency in Anbar was Khamis Sirhan al-Muhammad, the Ba'ath party regional chairman for the Karbala Governorate, who was originally No. 54 on the US list of most-wanted Iraqis. According to the US military, Khamis received his funding and orders directly from Saddam, then still a fugitive.[38][39][40]

In June, American forces conducted Operation Desert Scorpion, a mostly unsuccessful attempt to root out the burgeoning insurgency. An isolated success occurred near Rawah, where American soldiers cornered and killed more than 70 fighters on 12 June and captured a large weapons cache.[41]

In general, American forces had difficulty distinguishing between Iraqi civilians and insurgents, and the civilian casualties incurred during the sweep increased support for the insurgency.[42] On 5 July, a bomb killed seven at a graduation ceremony for the first American-trained police cadets in Ramadi.[43] On 16 July, Mohammed Nayil Jurayfi, the pro-government mayor of Haditha, and his youngest son were assassinated.[44][45]

As the violence escalated, the US responded with what many Iraqis called the "senseless use of firepower" and "midnight raids on innocent men".[32] Human Rights Watch accused the Army of a pattern of "over-aggressive tactics, indiscriminate shooting in residential areas and a quick reliance on lethal force",[46] as well as using "disproportionate force".[46] For example, if Iraqi insurgents set off a land mine, the US would respond by dropping bombs on those houses with arms caches; when insurgents fired a mortar round at American positions near Fallujah, the Americans responded with heavy artillery.[47] American forces near Al Qaim conducted "hard knocks" on local residents, kicking in doors and manhandling individuals, only to discover they were innocent.[48] In an incident on 11 September, soldiers manning a checkpoint near Fallujah shot multiple rounds at both an Iraqi police truck and a nearby hospital, killing seven.[49] Soldiers also beat and abused Iraqi detainees.[50][51] There was a constant rotation of units through the governorate, which led to confusion among the American troops: Fallujah had five different battalions rotate through in five months.[52] Summing up the initial American approach to Al Anbar, Keith Mines, the CPA diplomat in Anbar Governorate, wrote:

What we have done over the last six months in Al Anbar has been a recipe for instability. Through aggressive de-Ba'athification, the demobilization of the army, and the closing of factories the coalition has left tens of thousands of individuals outside the political and economic life of this country.[37]

On 31 October, during Operation Abalone teams from A Squadron of the British SAS supported by Delta force assaulted insurgent held compounds/dwellings in the fringes of Ramadi, killing an estimated dozen insurgents and capturing four. The operation turned up evidence of foreign fighters, finding actual proof of an internationalist jihadist movement. One SAS operator was killed in the operation.[53] The SAS also operated covertly in Ramadi and Fallujah in October and November 2003 and other more remote parts of Al Anbar Governorate as part of Operation Paradoxical which was aimed at hunting down threats to the coalition.[1]

November–December 2003

During the insurgency's Ramadan Offensive, a military Chinook transport helicopter carrying 32 soldiers was shot down with an SA-7 missile near Fallujah on 2 November. Thirteen were killed and the rest wounded.[55][56] Following the shootdown, Fallujah was quiet for a few months.[57] On 5 November, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld announced that the Marines would return to Iraq early the next year and would take over Al Anbar Governorate.[58] As the Marines prepared to move in, there was a growing consensus that the 82nd had lost control of the area, although the only real problem was Fallujah.[59] Some Marine commanders, like Major General James Mattis and Lieutenant Colonel Carl Mundy, criticized the Army's tactics as "hard-nosed" and "humiliating the Sunni population", promising that the Marines would act differently.[60][61] Late that November, Operators from A Squadron SAS launched a heliborne assault on a remote farm in Al Anbar Governorate, after they came under fire from insurgents inside, air support was called in and hit the farm, after it was cleared; seven dead insurgents were found whom American intelligence believed were foreign fighters.[62] Riots in Fallujah and Ramadi followed the December capture of Saddam Hussein.[63] The capture of Saddam created significant problems in Anbar: instead of weakening the insurgency, many Anbaris were outraged over what they saw as the degrading treatment of Saddam. Saddam's removal allowed the insurgency to recruit fighters who had previously opposed the Americans but had remained passive out of hatred for Saddam.[26] As Saddam loyalists were killed or captured, leadership positions went to AQI-affiliated hardliners such as Abdullah Abu Azzam al-Iraqi, who was directly responsible for murdering government officials in 2004.[64][65] While the Ba'ath Party continued to play a major role in the insurgency, the balance of power had shifted to various religious leaders who were advocating a jihad against American forces.[66]

2004

January–March 2004

At the beginning of 2004, General Ricardo Sanchez, head of Multinational Force Iraq (MNF–I), claimed that the US had "made significant progress in Anbar Province."[67] However, CPA funds for the governorate were inadequate. A brigade commander in Fallujah was allocated only $200,000 a month, when he estimated that it would cost at least $25 million to restart the city's factories, which employed tens of thousands of workers.[68][Note 3] By February, insurgent attacks were rapidly increasing. On 12 February, United States Central Command (CENTCOM) commander General John P. Abizaid and Major General Chuck Swannack, the 82nd Airborne's commanding officer, were attacked while driving through Fallujah.[70][71] On 14 February, in an incident dubbed the "Valentine's Day Massacre", insurgents overran a police station in downtown Fallujah, killing 23 to 25 policemen and freeing 75 prisoners. The next day, the Americans fired Fallujah's police chief for refusing to wear his uniform and arrested the mayor.[72][73] In March, Keith Mines wrote, "there is not a single properly trained and equipped Iraqi security officer in the entire Al Anbar province." He added that security was entirely dependent on American soldiers, yet those same soldiers inflamed Sunni nationalists.[74] That same month General Swannack gave a briefing on Anbar where he talked about improved security, declared the insurgency there was all but finished, and concluded "the future for Al Anbar in Iraq remains very bright."[75]

The 82nd Airborne handed control of Al Anbar Governorate over to the I Marine Expeditionary Force (I MEF), also known as Multi-National Forces West (MNF-W), on 24 March.[Note 4] Nearly two-thirds of the Marines, including their commanders James T. Conway and James Mattis, had participated in the invasion in 2003.[80] Conway planned on gradually reestablishing control over Anbar using a methodical counterinsurgency program, showing respect for the population and training the Iraqi Army and police using military transition teams (based on the Combined Action Program used by the Marines during the Vietnam War).[81] During the transition of authority between the MEF and the 82nd Airborne it became obvious that western Iraq was going to be more problematic for the Marines than southern Iraq had been.[82]

On 15 March, 3rd Battalion 7th Marines operating near Al Qaim got into a firefight with Syrian border guards. On 24 March, several Marines and paratroopers were wounded in Fallujah when insurgents attacked the ceremony for transfer of authority.[83]

Just one week after the MEF had taken over Anbar, insurgents in Fallujah ambushed a convoy carrying four American mercenaries from Blackwater USA on 31 March, killing all of them.[84] An angry mob then set the mercenaries' bodies ablaze and dragged their corpses through the streets before hanging them over a bridge crossing the Euphrates.[85] The American media compared the attack on the mercenaries to the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, where images of American soldiers being dragged through the streets of Somalia prompted the United States to withdraw its troops.[86]

That same day five soldiers were killed in nearby Habbaniyah when their M113 armored personnel carrier was hit by a mine.[85] According to General Conway, it was the largest mine that had been used in Anbar to date; only a tailgate and a boot were recovered.[87]

First Battle of Fallujah

Al Jazeera kicked our ass.

In response to the killings, General Sanchez ordered the Marines to attack Fallujah, under direct orders from President George W. Bush and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.[88][89][90] General Conway and his staff initially urged caution, pointing out that the MEF had already developed a more nuanced long-term plan to reestablish control over Fallujah and that using overwhelming force would most likely further destabilize the city. They noted that the insurgents were specifically trying to "bait us into overreaction."[88] Despite these objections, General Sanchez wanted a sustained Marine presence in the city within 72 hours.[91]

The Marines began their attack, codenamed Operation Vigilant Resolve, on 5 April.[92] The overall ground commander in Anbar, 1st Marine Division commander General James Mattis, initially planned to use his only available units, 1st Battalion 5th Marines and 2nd Battalion 1st Marines. They would push in from the east and west and methodically contain the insurgents.[93] This plan was underway when on 9 April, General Sanchez ordered an immediate halt.[94]

The main reason behind this order was the coverage by the Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya television networks. The two networks had the only access to the city. They repeatedly reported that Marines were using excessive force and collective punishment, and their footage of dead babies in hospitals inflamed both Iraqi and world opinion.[95] General Conway later summed up their effect on the battle by saying, "Al Jazeera kicked our ass."[24] When the 2nd Iraqi Battalion[Note 5] was ordered to Fallujah, 30 percent of its soldiers refused or deserted, and within days over 80 percent of the police force and Iraqi National Guard in Anbar Governorate had deserted.[96] After two members of the Iraqi Governing Council resigned over the attack and five more threatened to do so, CPA Leader Paul Bremer and CENTCOM commander General John Abizaid were worried that Fallujah might bring down the Iraqi government and ordered a unilateral ceasefire.[97]

Following the ceasefire, the Marines held their positions and brought in additional units, waiting for what they assumed would be the resumption of their attack. General Mattis launched Operation Ripper Sweep while the Marines waited, pushing the 1st Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion (LAR) and 2nd Battalion 7th Marines into the farmlands around Fallujah and neutralizing many armed gangs operating along the local highways.[98] The 3rd Battalion 4th Marines also conducted a raid into nearby insurgent-held Karmah, which expanded into a major engagement lasting the rest of the month.[99] The Marines were able to keep their supply lines open, but withdrew for political reasons. President Bush refused to allow the resumption of the attack, but was also unhappy with the status quo, asking his commanders for "other options".[100]

Finally, General Conway proposed what was a workable compromise in his opinion: the Fallujah Brigade.[101] Led by former Iraqi Sunni elites, such as Jasim Mohammed Habib Saleh and Muhammed Latif, and made up largely of insurgents who had been fighting the Marines, the brigade was supposed to maintain order in the city while allowing the US to withdraw and save face.[102][103] On 10 May, General Mattis formally turned the city over and withdrew the following day.[104] The First Battle for Fallujah had resulted in 51 US servicemen killed and 476 wounded.[105] Iraqi losses were much higher. The Marines estimated that about 800 Iraqis were killed.[105] Reports differed on how many were civilians: the Marines counted 300, whereas the independent organization Iraq Body Count argued that 600 civilians had been killed.[106][107]

Four Marines and soldiers were awarded either the Navy Cross or Distinguished Service Cross for the battle.[108] Another Marine, Captain Douglas A. Zembiec of Echo Company 2nd Battalion 1st Marines, became known as the "Lion of Fallujah" for his actions during the assault.[109]

Ramadi and western Anbar in 2004

Outside of Fallujah, there were additional attacks on American positions in Anbar throughout the spring and summer of 2004.[110] They were part of a larger "jihad wave" that swept across the governorate in mid-April. Gangs of armed youths took to the streets, setting up impromptu roadblocks and threatening supply routes in eastern Anbar and around Baghdad.[98][111] At one point General Mattis feared a general uprising by the Sunni community, similar to the 1978 Tehran protests.[112] On 6 April, a force of 300 insurgents attacked Marine patrols throughout Ramadi in an attempt to relieve pressure on Fallujah. Sixteen US Marines and an estimated 250 insurgents were killed in heavy street fighting over four days.[113]

Nearly all members of a squad from 2nd Battalion 4th Marines were killed when they drove into an ambush in unarmored Humvees, the first time the Marines had lost a firefight in Iraq.[114][115] On 17 April, insurgents attacked a Marine patrol in the border city of Husaybah, leading to a series of engagements that lasted the whole day and resulted in five Marines and at least 120 insurgents killed.[110][116][117] Around the same time, on 14 April, a squad led by Corporal Jason Dunham was operating near Husaybah when one member of a group of Iraqis who were being searched by Dunham's squad threw a grenade at the squad. Dunham immediately threw himself on the grenade, receiving a mortal wound from the blast but saving his fellow squad members. He later became the first Marine since the Vietnam War to be awarded the Medal of Honor.[118]

Attempting to emulate the perceived success in Fallujah, US commanders in Ramadi responded to the 28 June transfer of sovereignty from the CPA to the Iraqi Interim Government by pulling most forces back to camps outside the city and focusing on securing a highway that ran through its center.[119][120] Fighting continued to escalate throughout Anbar Governorate. On 21 June, a four-man Scout Sniper team operating with 2nd Battalion 4th Marines in Ramadi was executed by a group of insurgents who had infiltrated their observation post.[114][121][122] In mid-July, General Mattis predicted that Anbar would "[go] to hell" if the Marines could not hold Ramadi.[123] On 5 August, Anbar Provincial Governor Abd al-Karim Barjas resigned following the kidnapping of his two sons by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Barjas appeared on television and publicly apologized for "cooperation with the infidel".[124] He was replaced by an interim governor until January 2005.[125][126][127] The head of the Ramadi police force was subsequently arrested for complicity with the kidnappings.[128]

That same month, an Iraqi battalion commander was captured by insurgents in Fallujah and beaten to death.[129] After his death, two Iraqi National Guard battalions near Fallujah promptly deserted, leaving their weapons and equipment to the insurgents.[89][130] Counterinsurgency expert John Nagl, serving in nearby Khaldiyah, said that his unit knew the local police chief was supporting the insurgency, "but assessed that he had to do so to stay alive."[129] Suicide bombers killed seven Marines from 2nd Battalion 1st Marines on 6 September, eleven Iraqi police near Baghdadi on 23 October, and eight Marines from the newly arrived 1st Battalion 3rd Marines one week later.[131][132][133][134] More than 100 Americans were killed in Anbar from May 2004 to October 2004.[4]

Prior to November, Iraqi Prime Minister Ayad Allawi invited representatives from Ramadi and Fallujah in an attempt to negotiate an end to the fighting, similar to his previous dealings with Shia leader Muqtada al-Sadr.[135] In September, with the blessings of the Americans, Allawi disbanded the discredited Fallujah Brigade and privately gave the Marines permission to begin planning an offensive to retake Fallujah.[89][136] In early October, Allawi stepped up his efforts, demanding that the representatives of Fallujah hand over Zarqawi or face a renewed assault. They refused.[89] Shortly before the Marine offensive began, Sheikh Harith al-Dhari, leader of the pro-insurgent Association of Muslim Scholars, said that "the Iraqi people view Fallujah as the symbol of their steadfastness, resistance and pride."[89][137]

Insurgency in 2004

Despite the return of sovereignty to the Iraqi Interim Government on 28 June, the insurgency was still viewed by many Iraqis as legitimate and the Iraqi government as agents of the United States. In late 2004, DIA officer Derek Harvey said that insurgents in Ramadi were receiving financing via Syria "to the tune of $1.2 million a month". This was disputed by a CIA officer, explaining that they "didn't see clear financing coming from Syria".[138] The insurgency continued to enjoy broad-based support throughout Iraqi society, showing few of the sectarian divisions which would become pronounced following the 2006 al-Askari Mosque bombing.[139] Shia Iraqis attacked Iraqi military units moving towards Fallujah, Shia leaders called on their supporters to donate blood for insurgents, and Muqtada al-Sadr referred to the insurgents in Fallujah as "holy warriors".[140] Some Shi'ia attempted to join the fighting.[141]

The first in a series of execution videos was released on 11 May by AQI, of its leader al-Zarqawi executing American citizen Nick Berg.[142][143] Many of these hostages, such as Kim Sun-il, Eugene Armstrong, Jack Hensley, and Kenneth Bigley, were taken to Zarqawi's base in Fallujah for execution.[144][145][146]

After the initial push into Fallujah, the US argued that Zarqawi was behind a series of car bombings throughout Iraq. There had been no large car bombings in Baghdad during the siege, and enough munitions and contraband had been uncovered to conclude that many "bombs and car bombs detonated elsewhere in Iraq may have been manufactured in Fallujah."[147] In contrast, there were 30 large car bombs in the two months following the creation of the Fallujah Brigade, and the Brigade was now seen by the US and Iraqi governments as a front for the insurgency.[148][149] The suicide bombings and the hostage videos made Zarqawi the public face of the Iraqi insurgency in 2004, even though his leadership was disputed by many Sunni nationalist commanders. By late 2004 the US government's bounty on his head matched Osama bin Laden's.[150][151] However, a senior US military intelligence official described the core of the insurgency in December 2004 as "the old Sunni oligarchy using religious nationalism as a motivating force."[138]

Second Battle of Fallujah

Hundreds of thousands of the nation's sons are being slaughtered."

The order by Allawi to attack Fallujah again came on 6 November, just four days after George W. Bush was reelected as president.[154][155] 1st Marine Division commander General Richard F. Natonski assembled an ad hoc force of six Marine battalions, three Army battalions, three Iraqi battalions, and the British Black Watch Regiment. The insurgents, loosely led by Zarqawi, Abdullah al-Janabi, and Zarqawi's lieutenant Hadid, had replaced their losses and reportedly now had between 3,000 and 4,000 men in the city. They planned to hinder the Marine advance with roadblocks, berms, and mines, while conducting attacks outside the city to tie down Marine units.[156][157]

The attack began on 7 November when General Natonski had the 3rd LAR and 36th Iraqi battalions seize the city's hospital, located on a peninsula just west of the city.[158] The main attack began the night of 8 November. Coalition forces attacked from the north, achieving complete tactical surprise.[159]

The insurgents responded by attacking the Marines in small groups, often armed with RPGs. According to General Natonski, many insurgents had seen pictures of the Abu Ghraib scandal and were determined not to be taken alive.[160] By 20 November, Marines had reached the southern boundary of the city, but pockets of insurgents still remained. The assault battalions divided the city into areas and crisscrossed their assigned areas in an attempt to find the insurgents.[161] Four days later Zarqawi released an audiotape condemning Sunni Muslim clerics for their lack of support, claiming "hundreds of thousands of the nation's sons are being slaughtered."[152] The fighting slowly ebbed and by 16 December the US had begun to reopen the city and allow residents to return.[162]

The battle was later described by the US military as "the heaviest urban combat Marines have been involved in since the battle of Hue City in Vietnam."[163] The official Marine Corps history recorded that 78 Marines, sailors, and soldiers died and another 651 were wounded retaking Fallujah (394 were able to return to duty).[164] One-third of the dead and wounded came from a single battalion, 3rd Battalion 1st Marines.[164] Eight Marines were awarded the Navy Cross, the US military's second-highest award for valor, three of them posthumously.[108][165] Sergeant Rafael Peralta was also unsuccessfully nominated for the Medal of Honor.[166]

Officials estimated they had killed between 1,000 and 1,600 insurgents and detained another 1,000 out of an estimated 1,500 to 3,000 insurgents who were believed to be in the city.[167][168][169][170] Aircraft dropped 318 precision bombs, launched 391 rockets and missiles, and fired 93,000 machine gun or cannon rounds on the city, while artillery units fired 5,685 rounds of 155 mm shells.[171] The Red Cross estimated that 250,000 out of 300,000 residents had left the city during the fighting.[172] A Baghdad Red Cross official unofficially estimated that up to 800 civilians were killed.[173]

The Battle of Fallujah was not a defeat—but we cannot afford many more victories like it.

The Second Battle of Fallujah was unique in the Anbar campaign, in that it was the only time the US military and the insurgents waged a division-level conventional engagement.[114] During the rest of the Anbar campaign, the insurgents never stood and fought in numbers that large.[175][176][177] The official Marine Corps history claimed that the battle was not decisive, because most of the insurgent leadership and non-local insurgents had fled beforehand.[178] Summing up the Marine Corps view, the United States Naval Institute's official magazine Proceedings said, "The Battle of Fallujah was not a defeat—but we cannot afford many more victories like it."[174]

2005

January–April 2005

Following the Second Battle of Fallujah, the Marines faced three main tasks: providing humanitarian assistance to the hundreds of thousands of refugees returning to the city, retaking the numerous towns and cities they had abandoned along the Euphrates in the run-up to the battle, and providing security for the Iraqi parliamentary elections scheduled for 30 January.[179] According to top Marine officials, the elections were designed to help enfranchise the Iraqi government by including Iraqi citizens in its formation.[180] Only 3,775 voters (2 percent of the eligible population) cast ballots in Anbar Province due to a Sunni boycott.[181][182] The simultaneous elections for the provincial council were won by the Iraqi Islamic Party, which suffered from a perceived lack of legitimacy but nevertheless would dominate the Anbar legislature until 2009.[182][183]

During the run-up to the elections, a CH-53E helicopter crashed near Al-Rutbah on 26 January, killing all 31 Marines and sailors, most of whom were members of 1st Battalion 3rd Marines and who had survived the Second Battle of Fallujah. This was the single deadliest incident for US troops in the Iraq War.[184] On 20 February, the Marines launched Operation River Blitz, their first major offensive of the year, centered in the western Euphrates River Valley against the cities of Ramadi, Hīt, and Baghdadi.[80][184][185] Different units adopted different strategies. In Fallujah, the Marines surrounded the city with berms, banned all vehicles, and required residents to carry identification cards.[114][186] In Ramadi, the 2nd BCT of the 28th Infantry Division focused on controlling the main roads and protecting the governor and government center.[187] In western Anbar, the 2nd Marine Regiment conducted search and destroy missions, described as "cordon and search", where they repeatedly pushed into enemy-controlled towns and then withdrew.[188][189] On 2 April, a group of up to 60 AQI fighters launched a major attack, described as "one of the most sophisticated" seen to date, on the Abu Ghraib prison. The insurgents used a barrage of mortars, coupled with a suicide car bomb, in an unsuccessful attempt to breach the prison, wounding 44 US troops and 13 detainees.[80][190][191][192]

Improvised Explosive Devices

By late February, a new threat emerged—the improvised explosive device (IED). In 2005, 158 Marines and soldiers were killed by IEDs or suicide bombers, more than half (58 percent) of that year's combat deaths in Anbar.[4] These numbers reflected a nationwide trend.[193] While IEDs had been used since the beginning of the insurgency, the early models had been crudely designed, using "dynamite or gunpowder mixed with nails and buried beside a road".[193] By mid-2005 the insurgents had refined their technique, triggering them by remote control, stringing artillery shells or missiles together, using solid foundations to magnify the explosion, and burying them under roadways to inflict maximum damage.[193][194] The US responded with a series of progressively more-sophisticated electronic jamming devices and other electronic warfare programs which eventually consolidated into the Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization.[195]

Unless there are people melting inside of Humvees, then it's not a real problem.

— Anonymous Marine on the IED threat[114]

On 17 February, Brigadier General Dennis Hejlik filed an urgent request with the Marine Corps for 1,200 Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles, specifically designed to withstand IED attacks, for use in Al Anbar Governorate. In his request, General Hejlik added, "The [Marines] cannot continue to lose ... serious and grave casualties to IED[s]."[196] The Marine Corps did not formally act on the request for 21 months.[197] Hejlik later claimed that he was referring to IEDs which "tore into the sides of vehicles", and that the Marine Corps had determined that simply adding more armored Humvees would provide adequate protection.[196] Whistleblower Franz Gayl disagreed, and wrote a report for Congress claiming that the request was shelved because the Marine Corps wanted to use the funds to develop the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle, a replacement for the Humvee not scheduled to become operational until 2012.[198] Some Army personnel complained that the Marines took an almost casual attitude towards IEDs. One Army officer in Ramadi complained that, after warning about the large number of IEDs on a particular route, he was told, "Unless there are people melting inside of Humvees, then it's not a real problem."[114]

Western Euphrates River Valley

By the spring of 2005, both the US and Iraqi governments concluded that the biggest problem facing Iraq was AQI's car bombings in Baghdad. But while the Iraqis wanted to concentrate on Baghdad's suburban belts where the vehicles were being assembled,[Note 6] MNF–I commander General George Casey concluded the real problem was pro-insurgent foreign fighters coming across the Syrian border.[199] He ordered the Marines to launch a campaign that summer to secure the Western Euphrates River Valley (WERV).[200][201][202]

On 7 May a platoon from 3rd Battalion 25th Marines near Haditha was nearly overrun by insurgents, but ultimately rescued by one of its non-commissioned officers who was later awarded the Navy Cross.[203] The next day the 2nd Marine Regiment began clearing insurgent havens in the WERV. The first major attack was Operation Matador, against the town of Ubaydi, which CENTCOM claimed was an insurgent staging area.[80][204] Both 3rd Battalion 25th Marines and 3rd Battalion 2nd Marines participated in the attack.[205] In most cases the insurgents vanished, leaving behind booby traps and mines.[206] At least nine Marines were killed and 40 wounded in the operation, but the insurgents apparently returned to the town afterwards.[207]

AQI was interested in the WERV too. Zarqawi had reclaimed his base in western Anbar, declared Al Qaim as his capital, and was also operating in Hit and the Haditha Triad.[175][202][205] On 8 May, the insurgent group Jamaat Ansar al-Sunna ambushed and killed a dozen mercenaries near Hīt.[208] Two days later, Anbar Governor Raja Nawaf Farhan al-Mahalawi was kidnapped and killed by insurgents near Rawah.[127][209] He was replaced by Maamoon Sami Rasheed al-Alwani.[127]

MEF then began a series of operations in July, under the aegis of Operation Sayeed; in addition to clearing AQI from the WERV, Sayeed was also an attempt to set the conditions for the Anbaris to participate in the December constitutional referendum.[210] They carried out countless operations, with names like New Market, Sword, Hunter, Zoba, Spear, River Gate, and Iron Fist, ultimately culminating in November's Operation Steel Curtain.[80][201] In August, the 3rd Battalion 25th Marines conducted Operation Quick Strike, a cordon and search operation in the Haditha Triad. Twenty Marines were killed in two days: six snipers were ambushed and killed by Jamaat Ansar al-Sunna on 1 August, and fourteen Marines were killed on 3 August when their Amphibious Assault Vehicle was hit by a mine outside of Haditha.[80][175][200][211][212]

By October, more Americans had been killed in Anbar than anywhere else in Iraq and senior Marines had switched from talk about victory to simply "containing the violence and smuggling at a level that Iraqi forces can someday handle."[213]

October–December 2005

On 5 November, the 2nd Marine Regiment launched Operation Steel Curtain against the border town of Husaybah.[207] The Marines reported that ten Marines and 139 insurgents died in the offensive. Medical workers in Husaybah claimed that 97 civilians were killed.[80][214] On 1 December, ten Marines from 2nd Battalion 7th Marines were killed by a massive IED while on a foot patrol in Fallujah.[80][215]

On 15 October, the people of Anbar went to the polls to decide whether or not to ratify the new constitution. While the turnout (259,919 voters or 32% of eligible voters) was significantly higher than in the January elections, the results were similar: about 97% of the voters rejected the constitution.[Note 7][216][217][218] On 15 December, there was a follow-up election for the Iraqi parliament. Turn-out was even greater: 585,429 voters, or 86% of eligible voters.[219]

AQI launched a series of attacks in Jordan in late 2005 that were partially based out of Anbar. The group had already unsuccessfully attacked the Trebil checkpoint along the Jordanian border with Anbar Governorate in December 2004.[220][221] In August, two US warships in Aqaba, the USS Kearsarge and the USS Ashland, were attacked with rockets; the cell which carried out the attacks then fled into Iraq.[222] On 9 November, three Iraqis from Anbar carried out suicide bombings in Amman, killing 60. A fourth bomber, also from Anbar, was caught.[223]

2006

Haditha killings

In May 2006, the Marine Corps was rocked by allegations that a squad from 3rd Battalion 1st Marines had gone "on a rampage" the previous November, killing 24 unarmed Iraqi men, women and children in Haditha.[224] The incident had occurred on 19 November 2005, following a mine attack on a convoy that killed Lance Corporal Miguel Terrazas. A squad of Marines led by Staff Sergeant Frank Wuterich had been riding in the convoy and immediately assumed control of the scene. Following the mine attack, the Marines stopped a white Opel sedan carrying five Iraqi men and shot them after they tried to run away,[225] before the platoon commander arrived and took charge. The Marines say they were then fired upon from a nearby house, and Wuterich's men were ordered "to take the house".[226] Both Iraqi and Marine eyewitnesses later agreed that Wutterich's squad cleared the house (and several nearby ones) by throwing in grenades, then entering the houses and shooting the occupants. They differed over whether the killings had been permitted under the rules of engagement. The Marines claimed that the houses had been "declared hostile" and that training dictated "that all individuals in a hostile house are to be shot."[227] Iraqis claimed the Marines had deliberately targeted civilians.[224] In addition to the five Iraqi men killed by the sedan, nineteen other men, women, and children were killed by Wutterich's squad as they cleared the houses.[228]

Internal investigations were started in February by the Multi-National Force – Iraq, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (which examined the actual killings), and Major General Eldon Bargewell (who examined the Marines' response to the killings).[229][230] A news article that alleged a massacre had occurred was published in March.[224] Haditha became a national story in mid-May due to comments made by anti-war Congressman and former Marine John P. Murtha.[231] Murtha incorrectly claimed the number of civilians killed was much higher than reported and that the Marines had "killed innocent civilians in cold blood."[232] Murtha's broader point about troop misbehavior was reinforced by news of another killing where a squad of Marines executed an Iraqi man and then planted an AK-47 near his body in Hamdania, near Abu Ghraib, as well as the controversial Internet video Hadji Girl, showing a Marine joking about killing members of an Iraqi family.[233][234][235]

The military's internal investigation was concluded in June. Though Bargewell found no evidence of a cover-up, his report seriously criticized the Marine Corps for what he described as "inattention and negligence" as well as "an unwillingness, bordering on denial" by officers, especially senior officers, to investigate civilian deaths.[230] MEF commander General Stephen Johnson later said that civilian deaths occurred "all the time", and did not find the high number of deaths to be particularly unusual. He referred to the deaths as "the cost of doing business on that particular engagement."[229] On 21 December 2006, the US military charged eight Marines in connection with the Haditha incident.[236] Four of the eight, including Wuterich, were accused of unpremeditated murder.[237] On 3 October 2007, the preliminary hearing investigating officer recommended that charges of murder be dropped and that Wuterich be tried for negligent homicide instead. Six defendants subsequently had their cases dropped and one was found not guilty. In 2012, Wuterich pleaded guilty to negligent dereliction of duty in exchange for all other charges against him being dropped.[238][239] At least three officers, including battalion commander Lieutenant Colonel Jeffrey Chessani, were officially reprimanded for failing to properly report and investigate the killings.[228]

Second Battle of Ramadi

In June 2006, Colonel Sean MacFarland and the 1st Brigade Combat Team (BCT) of the 1st Armored Division were sent to Ramadi.[240] Colonel MacFarland was told to "Fix Ramadi, but don't do a Fallujah."[241] Many Iraqis assumed the 1st BCT was preparing for exactly that type of operation, with over 77 M1 Abrams tanks and 84 Bradley Fighting Vehicles,[242][243] but Colonel MacFarland had another plan.[244] Prior to Ramadi, the 1st BCT had been stationed in the northern city of Tal Afar, where Colonel H. R. McMaster in 2005 had pioneered a new type of operation: "Clear, Hold, Build". Under McMaster's approach, his commanders saturated an area with soldiers until it had been cleared of insurgents, then held it until Iraqi security forces were gradually built to a level where they could assume control.[245] As in other offensive operations, many insurgents fled the city in anticipation of a big battle. The 1st BCT moved into some of Ramadi's most dangerous neighborhoods and, beginning in July, built four of what would eventually become eighteen Combat Outposts.[246][247] The soldiers brought the territory under control and inflicted many casualties on the insurgents in the process.[248][249] On 24 July, AQI launched a counterattack, launching 24 assaults, each with about 100 fighters, on American positions. Despite the reported presence of AQI leader Abu Ayyub al-Masri, the insurgents failed in all of their attacks and lost about 30 men. Several senior American officers, including General David Petraeus, later compared the fighting to the Battle of Stalingrad.[250][251] Despite the success, Multi-National Force – Iraq continued to view Ramadi as a secondary front to the ongoing civil war in Baghdad and considered moving two of Colonel MacFarland's battalions to Baghdad. Colonel MacFarland even publicly described his operations as "trying to take the heat off Baghdad."[252][253]

The Second Battle of Habbaniyah

U.S. Marines of the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marine Division, swept through urban sprawl between Ramadi and Fallujah in a series of operations (i.e. Operations RUBICON and SIDEWINDER), disrupting flow of Al-Qaeda and Sunni insurgents into both cities, and killing and capturing over 300 insurgents. Action centered around Kilo Company, nicknamed "Voodoo", in the towns of Husaybah, Bidimnah, and Julaybah on the outskirts of Ramadi. Kilo Marines killed or captured 137 insurgents; 4 Marines were killed in action, and 17 were wounded. Within Kilo itself, the squad most affected was "Voodoo Mobile", the vehicle-mounted element of the unit's HQ section. Of its 16 members, 12 were wounded and 3 killed between September and November 2006.

During the seven-month deployment, fighting between Al Qaeda and the Marines was largely sporadic but intense. While only a handful of large-scale firefights developed—mostly in the suburbs of Ramadi between Habbaniyah and Julaybah—contact between the two sides was nearly continuous. Kilo Company officers reported sniper fire on a daily basis, as well as IED strikes on over 200 of the 250 + vehicle patrols they mounted.[254]

Operations consisted of a mixed array of company-scale urban "sweep-and-clear" operations, census and suppression patrols, and static, fortified area-denial positions. The battalion was spread out along a 30 kilometer front from the western fringes of Fallujah to the eastern boundary of Ramadi.

During the battle, 14 Marines from the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines were killed and at least 123 were wounded. 12 of the 14 were killed by IED strikes, while the other two suffered mortal wounds from sniper fire.[255][256][257][258]

Awakening movement

As the 1st Brigade pushed into Ramadi, it began aggressively courting the local tribes for police recruits. This was critical because, according to Colonel MacFarland, "without their help, we would not be able to recruit enough police to take back the entire city."[259] After the Americans promised the tribal leaders in Ramadi that their men would not be sent outside of the city, the tribes began sending men into the police force. The number of Iraqis joining the police went from 30 a month before June 2006 to 300 a month by July.[247] AQI tried to blunt police recruitment by attacking one of the new Ramadi police stations with a car bomb on 21 August, killing three Iraqi police. They simultaneously assassinated the Sunni sheikh of the Abu Ali Jassim tribe, who had encouraged many of his tribesmen to join the Iraqi Police.[247][260] The AQI fighters hid the body instead of leaving it for the tribe, violating Islam's funeral rites and angering the tribe.[260] This was one of the catalysts for what became a tribal revolt against AQI. According to David Kilcullen, who would later serve as Senior Counterinsurgency Adviser to General Petraeus, the revolt began after AQI killed a sheikh over his refusal to give his daughters to them in marriage.[261]

During this time, one of Colonel MacFarland's subordinates, Lieutenant Colonel Tony Deane, had kept contact with a low-level sheikh from the Abu Risha tribe, Abdul Sattar Abu Risha.[262] In 2004 and 2005, Sattar's father and three of his brothers had been killed by AQI, but he had refused exile.[263][264] In early September, Sattar told Deane that his tribe and several others were planning to ally with the United States and throw out the Baghdad-based government. Dean informed Colonel MacFarland, who pledged to support Sattar as long as Sattar continued to back the Government of Iraq.[265][266] On 9 September, Sattar and former Anbar Governor Fasal al Gaood, along with 50 other sheikhs, announced the formation of the Anbar Awakening movement.[Note 8][266][268] Shortly after the meeting, Colonel MacFarland began hearing reports that off-duty Iraqi police operating as the military wing of the Awakening had formed a shadowy vigilante organization called "Thuwar al-Anbar". Thuwar al-Anbar conducted terror attacks against known AQI operatives, while Colonel MacFarland and his soldiers turned a blind eye.[269]

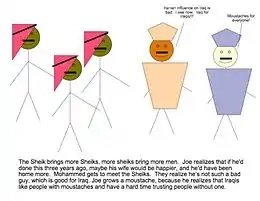

Colonel MacFarland asked his tribal adviser, Captain Travis Patriquin, to prepare a brief for the Iraqi government and the MEF's staff and journalists, all of whom remained skeptical about arming Sunni tribes who might someday fight the Shi'a-led government.[270] Patriquin's brief, called "How to Win in Al Anbar", used stick figures and simple language to convey the message that recruiting tribal militias into the police force was a more effective strategy than using the US military. Ricks referred to the briefing as "perhaps the most informal one given by the US military in Iraq and the most important one."[271] It later became a viral phenomenon on the Internet and is still used as a training aid.[272][273][274]

Following the formation of the Awakening movement, violence in Ramadi continued to increase. On 29 September 2006 an insurgent threw a grenade onto a rooftop where a group of Navy SEALs were positioned. One of them, Master-at-Arms Second Class Michael A. Monsoor, quickly smothered the grenade with his body and was killed. He was later awarded the Medal of Honor. On 18 October, AQI's umbrella organization, the Mujahideen Shura Council, formally declared Ramadi as a part of the Islamic State of Iraq.[275]

Operation Al Majid

MNF and ISF are no longer capable of militarily defeating the insurgency in al-Anbar.

— Colonel Peter Devlin, State of the Insurgency in al-Anbar, August 2006[276]

Even as the Awakening progressed, Anbar continued to be viewed as a lost cause. In mid-August, Colonel Peter Devlin, chief of intelligence for the Marine Corps in Iraq, had given a particularly blunt briefing on the Anbar situation to General Peter Pace, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[277] Devlin told Pace that the US could not militarily defeat AQI in Anbar, as "AQI has become an integral part of the social fabric of western Iraq." He added that AQI had "eliminated, subsumed, marginalized, or co-opted" all other Sunni insurgents, tribes, or government institutions in the province. Devlin believed that the only way to reestablish control over the province was to deploy an additional division to Anbar, coupled with billions of dollars of aid, or by creating a "sizeable and legally approved paramilitary force". He concluded that all the Marines had accomplished was preventing things from being "far worse".[278] In early September, Colonel Devlin's report was leaked to The Washington Post.[277][279] MEF commander Major General Richard Zilmer responded to press queries about the statement that Anbar Governorate was lost. Zilmer said that he agreed with the assessment, but added that his mission was only to train Iraqi security forces. He added that if he were asked to achieve a wider objective he would need more forces, but that sending more Americans to Anbar would not pacify the province—that the only path to victory was for the Sunnis to accept the Government of Iraq.[280]

Some of the first offensive operations outside of Ramadi also began in late 2006, with the construction of 8-foot (2.4-meter) high dirt berms around several Iraqi cities in western Anbar: Haditha, Haqlaniyah, Barwanah, Rutbah, and Anah. The berming was part of Operation Al Majid, an American-led operation to clear and hold more than 30,000 square miles (78,000 km2) in western Anbar.[281] Prior to Al Majid, a previous battalion commander had observed that his unit lacked the manpower to control both the main roads and towns of the Haditha Triad, that the Iraqi Army was as blind as they were, and that the insurgents were killing anyone who spoke to Coalition forces.[282] The 2nd Battalion 3rd Marines had lost over 23 Marines in just two months trying to hold the area.[283][284] In addition to the berms and the help of a local strongman known as Colonel Faruq, the Marines set up checkpoints in key locations to regulate entry and exit. By early January, attacks in the Triad had dropped from 10–13 per day to one every few days.[285]

The Iraq Study Group Report, released on 6 December, acknowledged that the Awakening movement had "started to take action", but concluded that "Sunni Arabs have not made the strategic decision to abandon violent insurgency in favor of the political process" and that the overall situation in Anbar was "deteriorating".[286] On the same day, Captain Patriquin was killed by a roadside bomb in Ramadi along with Major Megan McClung, the first female Marine officer to die in Iraq.[80][273][274][287] Following the execution of Saddam Hussein, Saddam's family considered interring him in Ramadi because of the improved security situation.[288] On 30 December, an unknown number of loyalists near Ramadi staged a march carrying pictures of Saddam Hussein and waving Iraqi flags.[289]

2007

Surge

In his State of the Union Address on 23 January 2007, President Bush announced plans to deploy more than 20,000 additional soldiers and Marines to Iraq in what became known as the Surge. Four thousand were specifically earmarked for Anbar, which Bush acknowledged had become both an AQI haven and a center of resistance against AQI.[290] Instead of deploying new units, the Marine Corps chose to extend the deployments of several units already in Anbar: 1st Battalion 6th Marines, 3rd Battalion 4th Marines, and the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU).[291] The 15th MEU would later be replaced by the 13th MEU as the last surge unit.[292][293]

AQI had its own offensives planned for 2007. In the first two months of 2007, it shot down eight helicopters throughout Iraq, including two in Anbar. One was brought down by a sophisticated SA-14 or SA-16 shoulder-fired missile on 7 February, near Karmah, killing five Marines and two sailors.[80][294] AQI also began a series of chlorine bombings near Ramadi and Fallujah. The first attack was on 21 October 2006, when a car bomb carrying twelve 120 mm mortar shells and two 100-pound (45 kg) chlorine tanks was detonated in Ramadi. The AQI campaign intensified in January 2007.[295] For five months, AQI carried out a series of suicide bombings in Anbar using conventional vehicle-borne explosive devices mixed with chlorine gas. The attacks in general were poorly executed, burning the chemical agent rather than dispersing it.[296][297][298][299]

AQI also continued its assassination campaign. On 19 February, AQI tried to kill Sheikh Sattar in his compound with a pair of suicide car bombs that missed the sheikh, but killed eleven. Several days later the Habbaniyah mosque of an imam who had spoken out against AQI was hit by a suicide bomber during Friday prayers, with 39 killed and 62 wounded.[300] In June, a group of Anbar sheiks meeting in Baghdad's Mansour Hotel was attacked by a suicide bomber, with 13 killed, including Fasal al Gaood, and 27 wounded.[301] On 30 June, a group of 70 AQI fighters planned to carry out a major attack on Ramadi targeting tribal leaders and police in the city, including Sheikh Sattar. Instead they stumbled into a squad from the 1st Battalion, 77th Armor Regiment near Donkey Island, and fought an all-night engagement that resulted in thirteen Americans dead or wounded and half the AQI fighters killed.[302]

MRAPs

As the campaign in Al Anbar entered its fourth year the Marine Corps scored a major victory when it adopted a vehicle originally designed in the 1970s to withstand mine attacks: the Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicle.[198][292] As early as 2004, the Marine Corps recognized that it needed a replacement for its armored Humvees. The few Cougar MRAP initially deployed yielded impressive results. In 2004, the Marines reported that no troops had died in over 300 mine attacks on Cougars.[303] In April 2007, General Conway estimated that the widespread use of the MRAP could reduce mine casualties in Anbar by as much as 80 percent.[304] Now Commandant of the Marine Corps, he requested an additional 3,000 MRAPs for Anbar and told the Joint Chiefs of Staff that he wanted to require every Marine traveling outside bases to ride in one. In April, the Deputy Commander for MEF said that in the 300 attacks on MRAPs in Anbar since January 2006, no Marines had been killed.[305] On 8 May 2007, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates stated that the acquisition of MRAPs was the Department of Defense's highest priority and earmarked 1.1 billion US dollars for them.[306] The Marine Corps purchased and fielded large numbers of MRAPs throughout 2007.[307][308][309] That October, General Conway described the MRAP as the "gold standard" of force protection.[310] Deaths from mine attacks plummeted and in June 2008, USA Today reported that roadside bomb attacks and fatalities in Iraq had dropped almost 90 percent, partially due to MRAPs.[311]

Operation Alljah

In June the Marine Corps launched Operation Alljah to secure Fallujah, Karma, Zaidon, and the Tharthar regions of eastern Anbar. These regions fell under the umbrella of Operation Phantom Thunder, an overall offensive throughout Iraq using US and Iraqi divisions on multiple fronts in an attempt to clear the areas surrounding Baghdad.[312][313] In late 2006, the 1st Battalion 25th Marines had turned Fallujah over to the Iraqi Army and Police, who preferred to stay in defensive checkpoints and not patrol the city. Colonel Richard Simcock, whose 6th Marine Regiment would retake the city, later admitted that the Marines had pulled out too soon.[314] In June, he sent the 2nd Battalion 6th Marines into Fallujah, dividing it up into ten precincts and sending Marines and Iraqi Police into each precinct in a duplication of 1st Battalion 6th Marines' operations in Ramadi.[315][316][317]

In May, General Gaskin began planning to retake the city of Karmah, which sat astride a main supply route between Fallujah and Baghdad and was an important insurgent stronghold. Unlike other locales, Karmah had no definable perimeter, making it easy for outsiders to access, as when insurgents fled to Karmah after being pushed out of Baghdad. Gaskin sent one of his aides to Jordan to meet with Sheikh Mishan, head of Karmah's largest tribe, the Jumayli. Sheikh Mishan fled to Jordan in 2005 after receiving threats from AQI. Gaskin's aide was able to persuade the sheikh to return in June, partnered with 2nd Battalion 5th Marines.[318][319][320] By October, insurgent attacks had dropped to almost zero.[321]

In May, the 13th MEU moved into Tharthar, a 970-square-mile (2,500 km2) area that was AQI's last Anbar refuge. Their goal was to cut off insurgent travel between Anbar and Saladin Governorates into Baghdad and to uncover weapons caches. Resistance was light and many insurgents fled. The insurgents laid over 400 mines to slow the Marines down. In one operation, Marines found 18 tons of homemade explosives and 48,000 pounds (22,000 kg) of ammonium nitrate fertilizer.[322] They uncovered several mass graves, containing a total of over 100 victims left behind by AQI. Tharthar was cleared by August.[322][323][324] Operation Alljah was one of the last significant Anbar offensives. By late October, weeks passed without casualties.[325]

America declares victory

When you stand on the ground here in Anbar ... you can see what the future of Iraq can look like.

— President George W. Bush, 3 September 2007[326]

President Bush flew to Al Asad Airbase in western Anbar Governorate on 3 September, to showcase what he referred to as a "military success" and "what the future of Iraq can look like".[326] While there, he met with top US and Iraqi leadership and held a "war council".[327] Frederick Kagan, one of the "intellectual architects" of the Surge, referred to the visit as the "Gettysburg" of the Iraq War and observed that Bush thought Anbar was "safe enough for the war cabinet of the United States of America to meet there with the senior leadership of the government of Iraq to discuss strategy."[328][329]

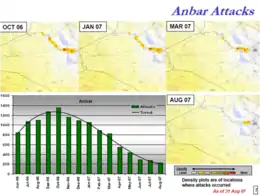

A week after Bush's visit, on 10 September, General David Petraeus, the Commanding General of Multi-National Force – Iraq, and United States Ambassador to Iraq Ryan Crocker gave their Report to Congress on the Situation in Iraq. General Petraeus specifically singled out Anbar Province as a major improvement, referring to the tribal uprisings there as "the most significant development of the past 8 months". He mentioned the dramatic improvements in security, stating that enemy attacks had decreased from a high of 1,350 in October 2006 to approximately 200 in August 2007.[330] Ambassador Crocker referred to Anbar Governorate in his Congressional testimony. He was careful to credit the victory to AQI "overplay[ing] its hand" and to the tribal uprising being directed primarily against the "excesses" of AQI. He also referred to the Government of Iraq recruiting "21,000 Anbaris [in] police roles", a carefully chosen phrase as many of them were tribal militia.[331] The two referred to Anbar Province a total of 24 times in their testimony.[332]

Three days later, on 13 September, Sheikh Sattar and three other men were killed by a bomb planted near his house in Ramadi.[333] AQI claimed responsibility for the attack and twenty people were arrested in connection with the killing, including the Sheikh's own head of security.[334] About 1,500 mourners attended Sheikh Sattar's funeral, including senior Iraqi and American officials. The leadership of the Anbar Salvation Council then passed to Sheikh Sattar's brother Sheikh Ahmed Abu Risha.[335] In December, al-Qaeda deputy leader Ayman al-Zawahiri released an interview where he denied that the tribes of Anbar Province were supporting the Americans, praising them as "noble and honorable" and referring to the Awakening as "scum".[332]

2008–2011

Transition

Beginning in February 2008, US forces began returning political and military control of Anbar to Iraqis. On 14 February, 1st Battalion 7th Marines withdrew from Hīt.[80] Two days later, American and Iraqi forces conducted a joint heliborne operation meant to show off the Iraqi security forces.[80] More significantly, in late March, both Iraqi Army divisions in Anbar Governorate, the 1st and 7th Divisions, were sent south to participate in the Battle of Basra.[336] Their participation helped win the battle for the government forces and showcased the major improvements to the Iraqi Army.[336] On 26 March 2008, B Squadron of the British SAS as part of Task Force Knight were called upon to hit a terrorist bomb-makers' house in the early hours. After trying to call him out and getting no response they stormed the house, receiving a hail of fire that left four men wounded while a terrorist from another building joined in the firefight. With helicopter support, they pressed on and chased their targets into another house that used civilians as hostages who were then accidentally killed alongside the terrorists. One SAS operator was killed.[337]

We do not deny the difficulties we are facing right now. ... The Americans have not defeated us, but the turnaround of the Sunnis against us had made us lose a lot and suffer very painfully.

Earlier in January, AQI leader Ayyub al-Masri ordered his fighters in Anbar to "get away from the massive indiscriminate killings" and "refocus attacks on American troops, Sunnis cooperating closely with U.S. forces, and Iraq's infrastructure."[338] AQI also ordered its fighters to avoid targeting Sunni tribesman, and even offered amnesty towards Awakening tribal leaders.[338] On 19 April, al-Masri called for a month-long offensive against US and Iraqi forces.[339] In Anbar, that offensive may have begun four days earlier on 15 April, when 18 people (including five Iraqi police) were killed in two suicide bombings near Ramadi.[340] On 22 April, a suicide bomber drove his vehicle into an entry-control point in Ramadi manned by over 50 Marines and Iraqi police. Two Marines engaged the driver who detonated his bomb early, killing the guards and wounding 26 Iraqis. Both Marines were posthumously awarded the Navy Cross.[341][342] On 8 May, a group of insurgents crossed the Syrian border near Al Qaim and killed 11 Iraqi policemen and military officers.[343] That same day, four Marines were killed in a roadside blast in Lahib, a farming village just east of Karmah.[344] On 16 May, a suicide car bomber attacked a Fallujah police station, killing four and wounding nine.[345]

In June, it was announced that Al Anbar Governorate would be the tenth province to transfer to Provincial Iraqi Control, the first such Sunni region. This handover was delayed by bad weather and a suicide bombing on 26 June in Karmah at a meeting between Sunni Sheikhs and US Marines which killed more than 23 people, including three Marines.[346][347] In July, presidential candidate Barack Obama visited Ramadi and met with Governor Rasheed, Sheikh Abu Rish, and 30 other sheikhs and senior military personnel. In the meeting, Obama promised that "the United States will not abandon Iraq" (his opponent, John McCain, had visited Haditha in March 2008).[348][349][350] On 26 August, Iraqi leaders signed the Command and Control Memorandum of Understanding in a ceremony at the Anbar Governance Center, a step towards taking full control and responsibility for security from Coalition forces.[80] Less than a week later, on 1 September, the transition became official.[80][351]

Drawdown

The last major military action in Al Anbar Governorate occurred on 26 October 2008, when a group of Army Special Forces conducted a raid into Syria to kill Abu Ghadiya, the leader of a network of foreign fighters who were traveling through Syria.[352] Anbar continued to play a large role in the Iraqi insurgency. That same month AQI announced the formation of the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), an umbrella group led by Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, a cleric from Anbar.[353] After both Al-Baghdadi and Al-Masri were killed in Tikrit in April 2010, the US believed the new leader of AQI/ISI was Abu Dua al-Badri, a former Emir of Rawa who was married to a woman from Fallujah.[353]

In late 2008, US forces began accelerating their move out of cities across Iraq, turning over the task of maintaining security to Iraqi forces.[354] The Marines pulled out of both Fallujah and Haditha Dam in November and December.[80] Lance Corporal Brandon Lara from 3rd Battalion 4th Marines was the last American service member killed in Anbar, on 19 July 2009.[4] In early August, a unit of Marines operating in Anbar located and recovered the body of Navy Captain Scott Speicher, who had been missing in action since the 1991 Gulf War.[355] By 6 October 2009, the last two Marine Regiments had left, ending the American combat presence.[356] Experts and many Iraqis were worried that AQI might resurface and attempt mass-casualty attacks to destabilize the country.[354] There was a spike in the number of suicide attacks, and AQI rebounded in strength through November 2009 and appeared to be launching a concerted effort to cripple the government.[357][358]

When you leave Ramadi, or Anbar all together, what will your legacy be? It's total destruction. People will say you just came in, destroyed, and left.

— Iraqi Professor at the University of Anbar, February 2009[359]

There were a number of car bombings in Ramadi, Haditha and Al Qaim following the US withdrawal from Iraqi cities on 30 June.[360] Throughout the last months of the year, additional attacks, mainly assassinations, occurred around Fallujah and Abu Ghraib.[361] In October, twin bombings killed 26 people and wounded 65 at a reconciliation meeting in Ramadi.[362] In December, a coordinated double suicide bombing outside Ramadi's government compound killed 25 people and severely wounded Governor Qasim Al-Fahdawi, who lost an arm.[361]

Violence continued through the last months of 2011. In September, a bus carrying Shia pilgrims from neighboring Karbala Governorate was stopped outside of Ramadi and 22 were executed, prompting threats from Karbala to annex parts of southern Anbar, including the city of Nukhayb.[363] In November, the provincial council in Anbar announced that it was considering whether to form a semi-autonomous region with other governorates in the Sunni areas of Iraq.[364]

As the Americans withdrew, many Iraqis and Americans questioned the ability of the Iraqi security forces, especially the police, to protect the province. Others expressed skepticism over whether Iran would dominate Iraq and whether the Iraqi government would be able to provide security.[365][366] One angry Iraqi described the American legacy as "total destruction ... you just came in, destroyed, and left."[359] Discussing the American withdrawal, a journalist in Fallujah predicted that the Government of Iraq would continue to have trouble with Anbar Province, saying, "Anbar was where instability began in Iraq. It was where stability returned. And it is where instability could start again."[367]

Withdrawal

The United States military in Al Anbar Governorate had a series of reorganizations in late 2009 and early 2010. The last non-American foreign forces left Iraq on 31 July 2009 and Multi-National Forces West became United States Force – West.[368][369] On 23 January 2010, the Marines formally left both Anbar Governorate and Iraq, transferring American military commitments over to the United States Army's 1st Armored Division.[78][370] The Army promptly merged United States Division West with United States Division – Baghdad, creating United States Division – Center to advise Iraqi forces in both Anbar and Baghdad.[369][370] In December 2010, the 25th Infantry Division assumed responsibility for Anbar Province.[371] On 7 December, the United States transferred its last base in Anbar, Al Asad, to the Iraqi Government.[372] One week later, hundreds of Fallujah residents celebrated the pullout by burning American flags in the city.[373][374]

Human rights abuses

[Y]ou would get civilian casualties. I mean, whether it's a result of our action or other action, you know, discovering 20 bodies, throats slit, 20 bodies, you know, beheaded, 20 bodies here, 20 bodies there.

— American officer on human rights abuses in Anbar in late 2005[375]

Both sides committed human rights abuses in Anbar Province, often involving civilians caught in the middle of the conflict. By late 2005, abuses had gotten so common that one American officer nonchalantly referred to "discovering ... 20 bodies here, 20 bodies there" and the head of MNF-W referred to them as "a cost of doing business."[375] During Operation Steel Curtain, insurgents forced their way into peoples' houses and held them hostage while engaging in gun battles with American forces, who often destroyed the homes.[376] One Sunni Iraqi family described how in 2006 they fled the sectarian violence in Baghdad to Hīt. During their yearlong stay in Hīt, they watched AQI fighters kidnap a man for talking back to them; the fighters later dumped the man's body on his doorstep. The family also watched an American patrol hit a mine in front of their house, and worried that the Americans would conduct reprisal killings on the family.[377] An Iraqi sheikh spoke about how he was accidentally shot and arrested by the Americans and thrown in Abu Ghraib prison where he was tortured. After his release he was targeted by insurgents in Fallujah who thought he was an American spy.[378]

By the Coalition

For the American forces, abuses were typically either a disproportionate use of firepower or servicemen committing extrajudicial killings (such as in Haditha). Many accusations of human rights violations against the United States were connected with the First and Second Battles of Fallujah. Following the assault, the United States military admitted it had employed white phosphorus artillery rounds, the use of which is not permitted in civilian areas under the United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons.[379][380][381] Several Marines, all of them from the 3rd Battalion 1st Marines, were later charged (but not convicted) with executing Iraqi prisoners.[382][383] Some British advisers also complained that the Marines had little regard for civilian casualties and had used munitions containing depleted uranium that caused birth defects for years after the battle.[384][385]

American forces also killed civilians through aerial bombing.[214] Between 2003 and 2007, 1,700 Iraqis on all sides were killed by aerial attack in Anbar Governorate.[7] On 19 May 2004, 42 civilians were killed near Al Qaim when American planes mistakenly bombed a wedding party.[386][387][388] In November 2004, 59 civilians were killed when the US bombed Fallujah's Central Health Center.[389] In November 2006, an American airstrike in Ramadi killed 30 civilians.[390] Some accusations, such as the alleged bombing of a Fallujah mosque in April 2004 that killed 40, were later proven to be exaggerated or false.[391]

An unknown number of Iraqis in Anbar were also killed through Escalation of Force (EOF) incidents, where American troops were allowed to fire at suspicious-looking Iraqi vehicles and persons under their rules of engagement. These incidents typically occurred at both coalition checkpoints and near coalition convoys on the road.[392][Note 9] One civil affairs officer recounted two separate incidents in Ramadi where families in cars were fired on for not stopping at checkpoints: in one incident the husband was killed; in another, the wife died and a boy was critically wounded.[393]