Juan Bautista Alberdi

Juan Bautista Alberdi (August 29, 1810 – June 19, 1884) was an Argentine political theorist and diplomat. Although he lived most of his life in exile in Montevideo, Uruguay and in Chile, he influenced the content of the Constitution of Argentina of 1853.

Juan Bautista Alberdi | |

|---|---|

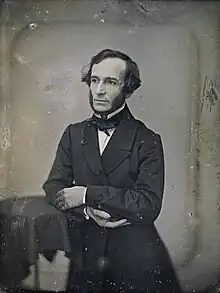

Daguerreotype taken in Chile, dated between 1850 and 1853 | |

| Born | August 29, 1810 |

| Died | June 19, 1884 (aged 73) Neuilly-sur-Seine, France |

| Resting place | House of government of Tucumán |

| Other names | Figarillo |

| Notable work | Bases y puntos de partida para la organización política de la República Argentina |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Generation of '37's Classical liberalism - May Association |

| Language | Spanish |

Main interests | Politics Law |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Based on his classical liberal and federal constitutional ideas, Alberdi at the same time tried to satisfy contrary social interests and establish a balance between national political centralization and provincial administrative decentralization: considering that both solutions would contribute to the consolidation and development of the original being of the single nation.[1]

Biography

Early life

Juan Bautista Alberdi was born in San Miguel de Tucumán, capital city of the Tucumán Province, Argentina, on August 29, 1810. His father, Salvador Alberdi, was a Spanish Basque merchant; his mother, Josefa Aráoz y Balderrama, had been born into an Argentine family of Spanish descent. She died as a result of Juan Bautista's birth. Salvador Alberdi supported the patriots during the Argentine War of Independence, and had interviews with general Manuel Belgrano during the Second Upper Peru campaign that was fought in Tucumán and northern areas in 1812 and 1813.[2] His father died as well in 1822; as he was still a minor his siblings Felipe and Tránsita became his legal guardians.[3]

He got a scholarship to the School of Moral sciences (today's '"Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires") in Buenos Aires, along fellow Tucuman Marco Avellaneda. He studied alongside Vicente Fidel López and Esteban Echeverría. He could not endure the harsh discipline of the school, and briefly left his studies pretending to be sick. He became interested in music, but preferred to learn it through autodidacticism rather than through formal artistic education. He wrote his first book in 1832, El espíritu de la música (Spanish: The spirit of music). He got a job with Juan Maldes, a friend of his family, and continued the informal learning of his other studies. He resumed his formal studies in 1831, and moved to the University of Córdoba. He returned to his province for family business, and wrote Memoria descriptiva sobre Tucumán (Spanish: Descriptive report of Tucumán) at the request of governor Alejandro Heredia. He declined the governor's request to stay in Tucumán, and returned to Buenos Aires.[4][5]

Like many other nineteenth century Argentines prominent in public life, he was a freemason.[6]

Civil war

Once in Buenos Aires, Alberdi became friends with Juan María Gutiérrez and Esteban Echeverría. They established the "Generation of '37", a group of liberal intellectuals that met at the Marcos Sastre literary hall. They criticized both factions of the Argentine Civil Wars, deeming the federalists too violent and the unitarians incapable to rule. They thought that both factions should end their disputes and work together. The governor Juan Manuel de Rosas forced Marcos Sastre to close the hall. Alberdi established then a women's magazine, "La Moda" (Spanish: The fashion), writing with the pseudonym "Figarillo". Despite of the main focus, the magazine contained political content as well. Alberdi was concerned about the legal system of Argentina as well, and wrote Fragmento preliminar al estudio del derecho (Spanish: Preliminary fragment of the study of law) to point problems and suggest solutions. The members of the Generation of '37 continued as a secret society, known as the "May Association" (in reference to the May Revolution), but the government discovered it. Most members emigrated to other countries; Alberdi emigrated to Uruguay in 1838.[7]

In Montevideo he got a degree as lawyer: he had already finished his studies in Buenos Aires, but refused to make the oath under Rosas' government.[8] Alberdi thought that the real problem in Argentina was not specifically Rosas, but the society that supported him. As a result, he thought that the generation of '37 should understand the reasons of such popular support, and how to earn it for themselves.[9] He worked in antirosist publications, such as "El Grito Arjentino" (Spanish: The Argentine Cry) and "Muera Rosas" (Spanish: Death to Rosas). He also wrote theater plays, "La Revolución de Mayo" (Spanish: The May Revolution) and "El gigante Amapolas" (Spanish: The giant Poppies). The name of this last one was a word play with the last name of Rosas, as "Rosas" can be also understood in the Spanish language as the plural form of "Rosa", the Rose flower. Alberdi worked as well as secretary to Juan Lavalle, who made a military campaign against Rosas during the French blockade of the Río de la Plata, but left him for political disagreements. Manuel Oribe, president of Uruguay deposed during the Uruguayan Civil War and allied to Rosas, laid siege to Montevideo in 1840, so Alberdi left the city and moved to Europe, alongside Juan María Gutiérrez.[10]

Alberdi met José de San Martín in Paris. The Argentine general of the war of independence was aged sixty-six at the time, Alberdi praised his modesty and vitality. Alberdi returned to the Americas in 1843. He tried to meet the former Argentine president Bernardino Rivadavia during his brief stay in Rio de Janeiro, to no avail. He settled in Valparaíso, Chile. He renewed his degree as lawyer, and worked both as a lawyer and journalist, again with the pseudonym "Figarillo". He studied the United States Constitution, seeking ideas that might work in Argentina, and wrote Sobre la conveniencia de un Congreso General Americano (Spanish: About the convenience of a General American Congress) in 1844. He established the newspaper El Comercio, and wrote the report La República Argentina 37 años después de su Revolución de Mayo (Spanish: The Argentine Republic 37 years after its May Revolution) in 1847, calling for an end to the disputes between parties. Rosas was finally defeated by Justo José de Urquiza in 1852, during the battle of Caseros.[11][12]

Diplomacy

With Rosas deposed, Urquiza called the San Nicolás Agreement and convened a constituent assembly. Alberdi supported the project and wrote Bases y puntos de partida para la organización política de la República Argentina (Spanish: Bases and starting points for the political organization of the Argentine republic), a draft for the new constitution. It was published by the printing house of the El Mercurio newspaper. It is heavily influenced by the United States Constitution. Alberdi complemented this work with Elementos de derecho público provincial Argentino (Spanish: Elements of Argentine provincial civic law), a comparison between the Argentine Constitution of 1826 and the United States Constitution. He attributed most of the problems of Argentina to its low population density, as the country had a very small population for its huge size; he frequently described the countryside as a desert. His proposed solution was to promote an influx of European immigration. His most known quotation is "Gobernar es poblar" (Spanish: To govern is to populate). He proposed as well to improve the infrastructure in ports, roads and bridges, and introduce the recently invented telegraphy and rail transport in the country. He advocated as well for economic freedom, rejecting the protectionism of Rosas' government.[13]

Urquiza, the new president of Argentina under the 1853 constitution, supported Alberdi's work, and appointed him ambassador of the Argentine Confederation in Chile. By that time, Buenos Aires seceded from the Confederation as the State of Buenos Aires. The writer Domingo Faustino Sarmiento opposed Urquiza, and extended his criticism to Alberdi. Sarmiento thought that Urquiza was just another caudillo similar to Rosas; and Alberdi thought that the State of Buenos Aires was keeping the policies of Rosas regarding the relations between Buenos Aires and the other provinces and the national organization. Alberdi's ideas on the issue were detailed in the Cartas Quillotanas, written from Quillota. Sarmiento wrote his answer in Las ciento y una.[14] Urquiza proposed Alberdi to be the minister of finances, he declined the offer. Urquiza gave him another appointment: move to Europe and seek recognition for the 1816 Argentine Declaration of Independence and its constitution, and prevent recognition for the state of Buenos Aires as a different country. Alberdi visited the United States in his way to Europe, and had an interview with the American president Franklin Pierce. He visited London, meeting Queen Victoria, and finally settled in Paris. He would stay in this city for 24 years.[15]

Alberdi met the French emperor Napoleon III, who granted the French recognition to the Confederation. Alberdi convinced him as well to remove the French diplomat at the State of Buenos Aires, and send another to the Confederation instead. Alberdi began negotiations with the marquis Pedro José Pidal for the Spanish recognition of the Argentine independence in 1857. He proposed two treaties between both countries: in the first, Spain would decline further sovereignty claims over the Argentine territory, and the second opened the country to commerce. He proposed as well that the Confederation would take the international debt of the former Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, the predecessor State of Argentina under Spanish rule; excluding those belonging to Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay (who had also been part of the viceroyalty, but became different countries). The treaties were signed in 1857 and 1859, and ratified on February 26, 1860. The Spanish queen Isabella II confirmed the treaties. However, the governor of Buenos Aires Carlos Tejedor rejected Alberdi's negotiations.[16]

He also met Rosas, who was living in Southampton since he left power. The Argentine Confederation and the State of Buenos Aires were reunified in 1861, which ceased Alberdi's work as ambassador. He opposed the War of the Triple Alliance, and began a controversy about it with president Bartolomé Mitre. In this time he began to write El crimen de la guerra, a book that he did not finish and was published posthumously in 1895.[17]

Late life

Alberdi returned to Argentina in 1879, after more than forty years living abroad. He had been appointed representative for Tucuman, but was rejected during the rebellion of Carlos Tejedor against Julio Argentino Roca. The civil war ended in 1880 with the federalization of Buenos Aires. Alberdi had received a number of recognitions by this time. The village of Alberdi in Santa Fe Province (which was later incorporated to Rosario as Barrio Alberdi) was named after him, and President Roca sent a bill to Congress to have all of Alberdi's works published. The newspaper La Nación, established by Mitre, criticized those recognitions. Alberdi was sent to Europe, he had a stroke during the journey. His health rapidly declined, and he died near Paris on June 19, 1884.[18]

Legacy

Juan Bautista Alberdi was one of the most notable exponents of the 1837 generation, which allowed to imagine and begin the construction of a prosperous Argentina with full freedoms. In the field of ideas, Alberdi achieved victory and bequeathed to all Argentines a country project, a model of organization and coexistence based on rules, norms, values and ethics. He is also recognized as a great jurist.[19]

His political as well as his economic projects are supported by contemporary Argentine classical liberal and libertarian economists such as Javier Milei, Agustín Etchebarne, Roberto Cachanosky among others.[20]

Selected bibliography

- El espíritu de la música – 1832

- Memoria descriptiva sobre Tucumán – 1834

- Fragmento preliminar al estudio del derecho – 1837

- Sobre la conveniencia de un Congreso General Americano – 1844

- Bases y puntos de partida para la organización política de la República Argentina – 1852

- Elementos de derecho público provincial Argentino – 1852

- Grandes y pequeños hombres del Plata – 1864

References

Footnotes

- Argüello, Santiago; Cavallo, Yanela (14 October 2020). "Liberalismo y Federalismo: De Constant a Alberdi". Revista de Historia Americana y Argentina. 55 (2): 127–150.

- Luqui-Lagleyze, p. 8.

- Lojo, p. 9.

- Lojo, pp. 9–10.

- Luqui-Lagleyze, pp. 8–9.

- The list includes Juan Bautista Alberdi, Manuel Alberti, Carlos María de Alvear, Miguel de Azcuénaga, Antonio González de Balcarce, Manuel Belgrano, Antonio Luis Beruti, Juan José Castelli, Domingo French, Gregorio Aráoz de Lamadrid, Francisco Narciso de Laprida, Juan Larrea, Juan Lavalle, Vicente López y Planes, Bartolomé Mitre, Mariano Moreno, Juan José Paso, Carlos Pellegrini, Gervasio Antonio de Posadas, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, and Justo José de Urquiza; José de San Martín is known to have been a member of the Lautaro Lodge, but whether that lodge was truly masonic has been debated: Denslow, William R. (1957). 10,000 Famous Freemasons. Vol. 1–4. Richmond, VA: Macoy Publishing & Masonic Supply Co Inc.

- Luqui-Lagleyze, pp. 9–11.

- Lojo, p. 10.

- Luqui-Lagleyze, pp. 11–12.

- Luqui-Lagleyze, p. 12.

- Lojo, p. 10.

- Luqui-Lagleyze, pp. 12–16.

- Luqui-Lagleyze, pp. 16–19.

- Lojo, pp. 10–11.

- Luqui-Lagleyze, pp. 19–22.

- Luqui-Lagleyze, pp. 22–23.

- Lojo, p. 11.

- Lojo, pp. 11–12.

- "El eterno legado de Juan Bautista Alberdi".

- Quieren que el Partido Liberal Libertario tenga candidato en 2019", Visión Liberal, Retrieved 17 February 2018 (in Spanish)

Further reading

- Alberdi y su tiempo, Jorge M. Mayer, Buenos Aires, Eudeba, 1963.

- Las ideas políticas en la Argentina, José Luis Romero, Buenos Aires, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1975.

- Vida de un Ausente, José Ignacio Garcia Hamilton, Buenos Aires, Editorial Sudamericana, 1993.

External links

- Works by or about Juan Bautista Alberdi at Internet Archive

- Free scores by Juan Bautista Alberdi at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Newspaper clippings about Juan Bautista Alberdi in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW