Alcázar of Seville

The Royal Alcázars of Seville (Spanish: Reales Alcázares de Sevilla), historically known as al-Qasr al-Muriq (Arabic: القصر المُورِق, The Verdant Palace)[1][2] and commonly known as the Alcázar of Seville (pronounced [alˈkaθaɾ]), is a royal palace in Seville, Spain, built for King Peter of Castile.[3] It was built by the Castilians on the site of an Abbadid alcázar, or residential fortress.[4][5] The fortress was destroyed after the Castilian conquest of Seville in 1248.[6]

| Royal Alcázars of Seville | |

|---|---|

| Native name Spanish: Reales Alcázares de Sevilla | |

.jpg.webp) Patio de la Montería courtyard | |

| Type | Alcázar |

| Location | Seville, Spain |

| Coordinates | 37°23′02″N 5°59′29″W |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, vi |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Part of | Cathedral, Alcázar and General Archive of the Indies in Seville |

| Reference no. | 383-002 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Type | Non-movable |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 3 June 1931 |

| Reference no. | RI-51-0001067 |

Location of Royal Alcázars of Seville in Spain | |

The palace is a preeminent example of Mudéjar style in the Iberian Peninsula, combining Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance structural elements. The upper stories of the alcázar are still occupied by the royal family when they visit Seville and are administered by the Patrimonio Nacional. It was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along with the adjoining Seville Cathedral and the General Archive of the Indies.[7]

Etymology

The term Alcázar comes from the Arabic al-qaṣr, ("the castle" or "the palace", اَلْقَصْر), itself derived from the Latin castrum ("castle").[8][9][10][11]

History

Islamic era

._Reales_Alc%C3%A1zares_de_Sevilla.jpg.webp)

In the year 712, Seville was conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate. In the year 913–914, after a revolt against Cordoba's government, the first caliph of Al-Andalus Abd al-Rahman III built a fortified construction in place of a Visigothic Christian basilica.[12] It was a quadrangular, roughly square enclosure about 100 meters long on each side, fortified with walls and rectangular towers, and annexed to the city walls.[13][14] In the 11th century, during the Taifa period, the Abbadid king Al-Mu'tamid expanded the complex southwards and eastwards,[13] with a new southern enclosure measuring approximately 70 by 80 meters.[14] This new palace was called Al Mubarak (Arabic: المبارك). Various additions to the construction such as stables and warehouses were also carried out.[12]

Towards 1150, the Almohad Caliphs began to develop Seville as their capital in Al-Andalus. The Almohad governor extended the fortified complex to the west, nearly doubling its size. At least six new courtyard palaces were constructed in the old enclosures and nine palaces were added in the western extensions.[14] In 1163 the caliph Abu Ya'qub Yusuf made the Alcazar his main residence in the region.[12][14] He further expanded and embellished the palace complex in 1169, adding six new enclosures to the north, south, and west sides of the existing palaces. The works were carried out by architects Ahmad ibn Baso and 'Ali al-Ghumari.[14] With the exception of the walls, nearly all previous buildings were demolished, and a total of approximately twelve palaces were built.[13] Among the new structures was a very large garden courtyard, now known as the Patio del Crucero, which stood in the old Abbadid enclosure. Between 1171 and 1198 an enormous new congregational mosque was built on the north side of the Alcazar (later transformed in to the current Cathedral of Seville). A shipyard was also built nearby in 1184 and a textiles market in 1196.[14]

There are few remnants of these Islamic-era constructions today. Archaeological remains of the Al Mubarak Palace are currently preserved under Patio de la Monteria. Several wall painting fragments were found that are now exhibited in the Palacio del Yeso.[12] The courtyard buildings now known as the Palacio del Yeso, the Palacio de la Contratación, and the Patio del Crucero all preserve remains from the Almohad period.[14]

Christian era

With the start of the Christian era in Seville, the Alcazar was converted into the residence of the Christian monarchs. Changes were made to the buildings to fit the needs of the monarchs and the court life. In the years 1364–1366, King Pedro I built the Mudéjar Palace, an example of the Andalusian Mudejar style. Under the Catholic rulers Isabella and Fernando, the upper floor was extended and transformed into the main residence of the monarchs.[12]

The palace was the birthplace of Infanta Maria Antonietta of Spain (1729–1785), daughter of Philip V of Spain and Elisabeth Farnese, when the king was in the city to oversee the signing of the Treaty of Seville (1729) which ended the Anglo-Spanish War (1727).[13]

The palace

- 1-Puerta del León

- 2-Sala de la Justicia y patio del Yeso (cyan)

- 3-Patio de la Montería (pink)

- 4-Cuarto del Almirante y Casa de Contratación (cream)

- 5-Palacio mudéjar o de Pedro I (red)

- 6-Palacio gótico (blue)

- 7-Estanque de Mercurio

- 8-Jardines (green)

- 9-Apeadero (yellow)

- 10-Patio de Banderas

The Real Alcázar is situated near the Seville Cathedral and the General Archive of the Indies in one of Andalusia's most emblematic areas.[13] During the five hundred years of construction, various architectural styles succeeded one another. There are no remnants of the initial design, but the structure was probably refurbished with elements of Islamic ornamentation and patterns. Several major gardens were also built. With the start of the Spanish Reconquista in the 13th century, the palace was remodeled with Gothic and Romanesque elements. The 16th century saw major additions built in Renaissance style. Alongside these designs, Islamic decoration and ornamentation was widely used. After damage by the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, that façade of the Palacio Gótico overlooking the Patio del Crucero was completely renovated using Baroque elements. The palace now presents a unique blend of styles.[15]

Tiles

The palace is known for its tile decoration. The two tile types used are majolica and arista tiles. In the arista technique, the green body is stamped and each tile segment has raised ridges. This technique produces tiles with transparent glazes that are not flat. The art of majolica ceramics was developed later in the 15th–16th centuries. The innovation made it possible to "paint" directly on ceramics covered with white opaque glazes. Being a trade center, Seville had access to large scale production of these tiles. They were mainly of geometric design inspired by arabesque ornamentation.

In the 16th century, the Catholic Monarchs commissioned an Italian artist from Pisa, Francisco Niculoso (called Pisano) to make two majolica tile altarpieces for their private chapel in the palace.[16] One still exists in the oratory of the royal apartments, the other one is missing. Later, the artist Cristóbal de Augusta created a tile-work in the Palacio Gotico. It features animals, cherubs and floral designs and gives the palace a bright tapestry look.[17]

Puerta del León

The main entrance to the Alcázar takes its name from the 19th century tile-work inlaid above it, a crowned lion holding a cross in its claws and bearing a Gothic script.

Patio de las Doncellas

The name, meaning "The Courtyard of the Maidens", is a reference to the apocryphal story that the Moors demanded an annual tribute of 100 virgins from the Christian kingdoms of Iberia.

The lower storey of the Patio was built for King Peter of Castile and contains inscriptions that refer to Peter as a "sultan".

Several reception rooms are arranged around a long rectangular reflecting pool that runs the entire length of the patio, creating a water line.[18] This pool is surrounded by promenades covered with a red brick pavement decorated with green ceramic borders, similar to the pavement that adorns the perimeter of the garden.[18] The pool and its promenades are bordered by two flowerbeds located one meter beneath the pavement[19] whose sides are decorated with a frieze of interlaced semi-circular arches.[20]

The current appearance is the result of a reconstruction carried out in the 21st century following the excavations carried out between 2002 and 2005 by a team of archaeologists led by Miguel Ángel Tabales.[21][22] The garden and the pool, built between 1356 and 1366, were buried between 1581 and 1584 and the courtyard was paved by Juan Bautista de Zumárraga with a white and black marble pavement with an alabaster fountain in the center.[18][19][20][21] The patio maintained this appearance until its true structure was discovered[23] and the hidden garden was uncovered after the 2002–2005 excavations, which revealed the good state of conservation of the area under the patio.[18][22] The ancient Mudejar garden was restored after being hidden for centuries under a marble floor.

Soon after this restoration, the courtyard was temporarily paved with marble once again at the request of English film director Ridley Scott. The paved courtyard was used as the set for the court of the King of Jerusalem in Scott's movie Kingdom of Heaven. The courtyard arrangement was converted once more after the film's production.

The patio de las Doncellas in 2000, with the marble pavement laid in 1581–1584.

The patio de las Doncellas in 2000, with the marble pavement laid in 1581–1584..jpg.webp) The current appearance, after the restoration of the Mudejar garden.

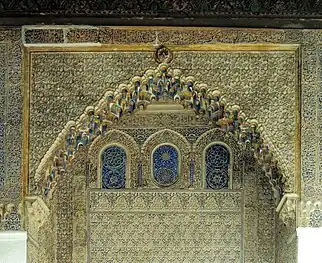

The current appearance, after the restoration of the Mudejar garden. Great arch with muqarnas in the patio de las Doncellas.

Great arch with muqarnas in the patio de las Doncellas.

The upper story of the Patio was an addition made by Charles V. The addition was designed by Luis de Vega in the style of the Italian Renaissance although he did include both Renaissance and mudéjar plaster work in the decorations. Construction of the addition began in 1540 and ended in 1572.

Los Baños de Doña María de Padilla

The "Baths of Lady María de Padilla" are rainwater tanks beneath the Patio del Crucero. The tanks are named after María de Padilla, the mistress of Peter the Cruel.

Salon de Embajadores

The Ambassadors Hall is the ancient throne room built during the reign of Al-Mu'tamid in the 11th century. In the 14th century, Pedro I of Castile remodeled the hall to make it a centerpiece of his royal palace. Plant motifs in plasterwork were added in the corners of the room and spandrels of the arches. Windows were traced with geometric elements. Walls were covered with tiled panels. The orientation of the hall was also changed from facing Mecca to northeast. The doorway now led to the Patio of the Maidens (Patio de las Doncellas).[24] In 1526, Emperor Charles V and Isabella of Portugal celebrated their marriage in this room.[25]

Other sections

- Patio de las Muñecas (Courtyard of the Dolls)

- Patio de la Montería (Courtyard of the Montería)

- Dormitorio de los Reyes Moros (Bedroom of the Moorish Kings)

- Sala de Justicia (Justice room)

- Patio del Yeso (Courtyard of the Plaster)

- Cuarto del Almirante (Admiral's Room)

- Casa de Contratación (Casa de Contratación)

- Patio del Crucero (Courtyard of the Crossing)

- Palacio Mudéjar or de Pedro I (Mudéjar Palace or that of Peter of Castile)

- Patio de las Muñecas (Courtyard of the Dolls)

- Cuarto del Príncipe (Prince's Room)

- Patio de las Doncellas (Courtyard of the Maidens)

- Salón del Techo de Carlos V (Charles V Ceiling Room)

- Salón de Embajadores (Ambassadors' Room)

- Salón del Techo de Felipe II (Philip II Ceiling Room)

- Primera planta (First level of the Palace of Peter of Castile)

- Palacio Gótico (Gothic Palace)

- Capilla (Chapel)

- Gran Salón (Big Room)

- Salón de los Tapices (Tapestries' Room)

- Sala de las Bóvedas (Vaults' Room)

- Upper floors belong to the Patrimonio Nacional and are occupied by the royal family when visiting Seville. There are many security measures for visitors; admission is approximately 5 euros.

- Vestíbulo or Saleta de la Reina Isabel la Católica (Lobby or Queen Isabella the Catholic Monarch's Room)

- Anteortaorio de Isabel la Católica (Pre-oratory of Isabella the Catholic Monarch)

- Oratorio de Isabel la Católica (Oratory of Isabella the Catholic Monarch)

- Alcoba Real (Royal Bedroom)

- Antecomedor (Pre-dining Room)

- Comedor de Gala (Gala Dining)

- Sala de fumar (Smoking Room)

- Retrete del Rey (King's Toilet)

- Antecomedor de familia, antiguo Cuarto del Rey (Family Pre-dining Room, former King's Room)

- Comedor de Familia or Cuarto Nuevo (Family Dining Room or New Room)

- Mirador de los Reyes Católicos (Viewpoint of the Catholic Monarchs)

- Dormitorio del Rey Don Pedro, antiguo Cuarto de los Lagartos (King Don Peter of Castile's Bedroom, former Lizards' Room)

- Despacho de Juan Carlos I (Juan Carlos I's Office)

- Cámara de Audiencias (Hearings' Chamber)

- Dormitorio de Isabel II (Isabella II's Bedroom)

- Colección Carranza (a museum of old azulejos)

- Gardens

- Estanque de Mercurio (Mercury Pond)

- Galería de Grutesco (Grotesque Gallery)

- Jardín de la Danza (Dance's Garden)

- Jardín de Troya (Troy's Garden)

- Jardín de la Galera (The Galley's Garden)

- Jardín de las Flores (Flowers' Garden)

- Jardín del Príncipe (Prince's Garden)

- Jardín de las Damas (Ladies' Garden)

- Pabellón de Carlos V (Charles V's Pavilion)

- Cenador del León (Lion's Gloriette)

- Jardín Inglés (English Garden)

- Jardín del Marqués de la Vega-Inclán (Marquis of la Vega-Inclán's Garden)

- Jardín de los Poetas (The Poets' Garden)

- Apeadero (Mounting-block)

- Patio de Banderas (Flags' Courtyard)

- Walls of the Alcázar

The gardens

All the palaces of Al Andalus had garden orchards with fruit trees, horticultural produce and a wide variety of fragrant flowers. The garden-orchards not only supplied food for the palace residents but had the aesthetic function of bringing pleasure. Water was ever present in the form of irrigation channels, runnels, jets, ponds and pools.

The gardens adjoining the Alcázar of Seville have undergone many changes. In the 17th century during the reign of Philip III the Italian designer Vermondo Resta introduced the Italian Mannerist style. Resta was responsible for the Galeria de Grutesco (Grotto Gallery) transforming the old Muslim wall into a loggia from which to admire the view of the palace gardens.

.jpeg.webp) Gallery of the Grottoesque

Gallery of the Grottoesque Garden of the poets

Garden of the poets The Pavilion of Charles V

The Pavilion of Charles V Avenue

Avenue The Portal of the Privilege

The Portal of the Privilege

In popular culture

- In 1962 the Alcázar was used as a set for Lawrence of Arabia.[26]

- The Patio de las Doncellas was used as the set for the court of the King of Jerusalem in the 2005 movie Kingdom of Heaven.

- Part of the fifth season of Game of Thrones was shot in several locations in the province of Seville, including the Alcázar.[27]

References

- Team, Almaany. "Translation and Meaning of مورق In English, English Arabic Dictionary of terms Page 1". www.almaany.com. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "مدينة إشبيلية الإسبانية". موضوع (in Arabic). Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Joseph F. O'Callaghan (15 April 2013). A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press. p. 692. ISBN 978-0-8014-6871-1.

- Frederick Alfred De Armas (1996). Heavenly Bodies: The Realms of La Estrella de Sevilla. Bucknell University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8387-5308-8.

- Titus Burckhardt (1997). Moorish Culture in Spain. Suhail Academy. p. 104.

- Antonio Urquízar-Herrera (11 May 2017). Admiration and Awe: Morisco Buildings and Identity Negotiations in Early Modern Spanish Historiography. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-879745-6.

- "Cathedral, Alcázar and Archivo de Indias in Seville". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- The Islamic Review. Woking Muslim Mission and Literary Trust. 1960. p. 2.

- T.W. Haig (1993). Houtsma MT, Wensinck AJ, Arnold TW, Heffening W, Lévi-Provençal É (eds.). E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. Vol. IV (Reprint of 1913 ed.). BRILL. p. 802. ISBN 9789004097902.

- Muḥammad ibn ʻUmar Ibn al-Qūṭīyah; David James (2009). Early Islamic Spain: The History of Ibn Al-Qūṭīya : a Study of the Unique Arabic Manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, with a Translation, Notes, and Comments. Taylor & Francis. p. 55. doi:10.4324/9780203882672. ISBN 978-0-415-47552-5.

- Jonathan Bloom; Sheila Blair (14 May 2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture: Three-Volume Set. OUP USA. p. 198. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195309911.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- Robador, M. D.; De Viguerie, L.; Pérez‐Rodríguez, J. L.; Rousselière, H.; Walter, P.; Castaing, J. (2016). "The Structure and Chemical Composition of Wall Paintings From Islamic and Christian Times in the Seville Alcazar". Archaeometry. 58 (58): 255–270. doi:10.1111/arcm.12218. ISSN 0003-813X.

- Tabales Rodríguez, Miguel Ángel (2001). "La transformación palatina del Alcázar de Sevilla, 914–1366" (PDF). Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa. 12: 195–213. hdl:10396/3559. ISSN 1130-9741.

- Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. pp. 197–210. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190624552.003.0004. ISBN 9780190624552.

- Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2004). "The Alcazar of Seville and Mudejar Architecture". Gesta. University of Chicago Press, International Center of Medieval Art. 43 (2): 87–98. doi:10.2307/25067097. ISSN 0016-920X. JSTOR 25067097. S2CID 192856091.

- Museum of International Folk Art (N.M.) (2003). Cerámica Y Cultura: The Story of Spanish and Mexican Mayólica. UNM Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0-8263-3102-1.

- de Viguerie, Laurence; Robador, Maria D.; Castaing, Jacques; Perez-Rodriguez, Jose L.; Walter, Philippe; Bouquillon, Anne (March 2019). "Technological evolution of ceramic glazes in the renaissance: In situ analysis of tiles in the Alcazar (Seville, Spain)" (PDF). Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 102 (3): 1402–1413. doi:10.1111/jace.15955. ISSN 0002-7820. S2CID 139974261. HAL hal-02179294.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Ana Marín Fidalgo (2006). Exposition Ibn Khaldoun: La Méditerranée au XIVe siècle – Le Real Alcázar de Séville (in French). Junta de Andalucia. p. 162.

- Antonio Almagro, Luis Ramon-Lac. "Patio de las Doncellas, Alcázar of Seville". doaks.org. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- "Alcazar royal de Séville, Espagne". hisour.com (in French). Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Tabales Rodrigues, Miguel Ángel (2003). "Investigaciones arqueológicas en el Patio de las Doncellas: Avance de resultados de la primera campaña (2002)". Apuntes del Real Alcázar de Sevilla (in Spanish) (4): 2–6. ISSN 1578-0619.

- EFE (6 September 2002). "La zona mudéjar que se halla bajo el Patio de las Doncellas de Sevilla se encuentra en 'óptimo' estado". El País (in Spanish).

- "Real Alcazar – Plus d'histoire". Real Alcazar Sevilla. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Blasco-López, F. J.; Alejandre, F. J.; Flores-Alés, V.; Cortés, I. (2016-03-15). "Plasterwork in the Ambassadors Hall (Salón de Embajadores) of the Real Alcázar of Seville (Spain): Graphic reconstruction of polychrome work by layer characterization" (PDF). Construction and Building Materials. 107: 332–340. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.01.021. hdl:11441/143490. ISSN 0950-0618. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-04. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- Giordano, Carlos; Palmisano, Nicolás; Caruncho, Daniel R. (2016). Real Alcázar de Sevilla : más de mil años de arte y arquitectura. Barcelona: Dos de Arte Ediciones. ISBN 9788491030423. OCLC 946119342.

- "El día que Lawrence de Arabia cambió el desierto por Sevilla". www.elmundo.es. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Mencos, Ana (31 August 2017). "¿Qué se ha visto de Sevilla en "Juego de Tronos"?". ABC (in Spanish). Vocento. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

External links

- InFocus: Alcázar of Seville (Sevilla, Spain) at HitchHikers Handbook

- Images of the Alcázar in Seville – 105 images with good descriptions of the Alcázar and its history.

- Casa de la Contratación – in depth historical article.

- El Real Alcázar de Sevilla (In Spanish, English and French)

- UNESCO World Heritage

- interiors and details pictures of Seville Alcazar