Alexander Cumming

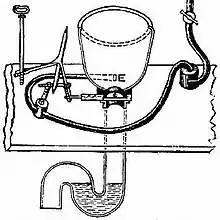

Alexander Cumming FRSE (sometimes referred to as Alexander Cummings; 1733 – 8 March 1814)[1] was a Scottish watchmaker and instrument inventor, who was the first to patent a design of the flush toilet in 1775, which had been pioneered by Sir John Harington, but without solving the problem of foul smells. As well as improving the flush mechanism, Cummings included an S-trap (or bend) to retain water permanently within the waste pipe, thus preventing sewer gases from entering buildings.[2][3] Most modern flush toilets still include a similar trap.

Alexander Cumming | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1731/2 Edinburgh, Scotland, UK |

| Died | 8 March 1814 (aged 82) Pentonville, England |

| Citizenship | British |

| Known for | Watchmaker Clockmaker First patent for a flush toilet (S-trap) Church organ designer Inventor of the first accurate Barograph Inventor of the microtome |

Early life

Cumming was a mathematician and mechanic as well as a watchmaker. Little is known of his early life. He was born in Edinburgh in 1733,[4] the son of James Cumming of Duthil.[5] He is recorded as having been apprenticed to an Edinburgh watchmaker.[1]

Career

In the 1750s he was employed by Archibald Campbell, 3rd Duke of Argyll, at Inverary as an organ builder as well as a clockmaker.[6] After his move to England he continued to work in both fields. The Earl of Bute and his family commissioned a series of elaborate barrel organs with which Cumming was involved.[7][8]

By 1763 he had premises in Bond Street, London, and "had acquired a sufficient reputation to be appointed a member of the commission set up in that year to adjudicate on John Harrison's ‘timekeeper for discovering the longitude at sea’".[6] He made a barometrical clock for King George III, who paid him an annual retainer for its maintenance.[9] Other barometrical clocks created by him are at the Science Museum in London, and on the Isle of Bute.[10]

He wrote books about watch and clock work, about the effect on roads of carriage wheels with rims of various shapes, and on the influence of gravity.

In 1765 he invented a clock for George III which also acted as a barometer, recording air pressure against time. This is notable as the first accurate recording barograph. In 1766 he made a similar model for his personal use, which on his death was purchased by Luke Howard who used it for his observations within the book The Climate of London.[5]

In 1770 he is credited with the invention of the microtome, a machine for making extremely thin slices as used in slide-preparation, in conjunction with John Hill.[11]

In 1775 he made major advances on the design of the flushing toilet. His improved valve closet incorporated a sliding valve to keep water in the pan and an S-bend trap in the waste pipe, preventing foul smells from re-entering the house and generally giving a "cleaner" solution.[12] He also linked the water inlet valve to the flush mechanism to allow the pan to be emptied and refilled by pulling a single handle.

With his brother he was involved in the development of the Pentonville district of London, where there is a Cumming Street running north from Pentonville Road. He had a house in the district and an organ shop.

In 1783 he was a joint founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and was made a Fellow.[6][13]

In 1788 Cumming is recorded as a watch and clock-maker on Bond Street in London, responsible for the design and manufacture of a church organ for the Church of the Holy Trinity in Christchurch, Cambridgeshire, having earlier created a "self-acting mechanism" already used for an organ for the Earl of Bute in 1787. In 1814 his final patent appears to be for "antisymmetrical bellows" for organ-use.[14]

Death

He died on 8 March 1814, in Pentonville, England. He was buried in the graveyard of St James' Chapel, Pentonville (since demolished), in what is now Joseph Grimaldi Park, where the famous clown was also buried. The park adjoins Cumming Street.

Honours

He became a magistrate in 1779. In 1781 he was made an honorary freeman of the Clockmakers' Company.

As a result of his making instruments for Capt. Phipps's voyage in the polar regions, the island of Cummingøya in Svalbard was named after him.[15]

Publications

- Elements of Clock and Watch Work Adapted to Practice (1766)

References

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "From Charles Mackintosh's waterproof to Dolly the sheep: 43 innovations Scotland has given the world". The independent. 30 December 2016. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016.

- "The Development of the Flushing Toilet – Detailed Chronology 1596 onwards". Stoke-on-Trent, UK: Twyfords Bathrooms. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "Archived item". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- "AIM25 collection description". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Gloria Clifton (2004), "Cumming, Alexander (1731/2–1814)" Archived 22 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Malloch (1983). "The Earl of Bute's Machine Organ: A Touchstone of Taste". Early Music. OUP. 11 (2): 172–183. doi:10.1093/earlyj/11.2.172. JSTOR 3137830. Accessed via JSTOR (subscription required)

- "Westmorland Lowther, Lowther Castle (Earl of Lonsdale) [N03604]". National Pipe Organ Register. British Institute of Organ Studies.

- Alexander Cumming. "Barometrical Clock". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 2752.

- Bute Collection; Decorative Arts Archived 5 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine; Mount Stuart online.

- "A. Cumming and J. Hill".

- "Archived item". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Cumming, Alexander (1731/2–1814) Archived 22 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Royal Society.

- Organa Britannica: Organs in Great Britain 1660–1860 by James Boeringer

- "Place names in Norwegian polar areas".

External links

Works related to Alexander Cumming at Wikisource

Works related to Alexander Cumming at Wikisource