Alexis Nour

Alexis Nour (Romanian pronunciation: [aˈleksis ˈno.ur]; born Alexei Vasile Nour,[1] also known as Alexe Nour, Alexie Nour, As. Nr.;[2] Russian: Алексе́й Ноур, Aleksey Nour; 1877–1940) was a Bessarabian-born Romanian journalist, activist and essayist, known for his advocacy of Romanian-Bessarabian union and his critique of the Russian Empire, but also for controversial political dealings. Oscillating between socialism and Russian nationalism, he was noted as founder of Viața Basarabiei gazette. Eventually affiliated with Romania's left-wing form of cultural nationalism, or Poporanism, Nour was a long-term correspondent of the Poporanist review Viața Românească. Publicizing his conflict with the Russian authorities, he settled in the Kingdom of Romania, where he openly rallied with the Viața Românească group.

Alexis (Alexei Vasile) Nour | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1877 Bessarabia |

| Died | 1940 |

| Occupation | journalist, translator, political militant, ethnographer, spy |

| Nationality | Imperial Russian, Romanian |

| Period | 1903–1940 |

| Genre | collaborative fiction, epistolary novel, essay, memoir, novella, sketch story |

| Literary movement | Poporanism, Constructivism |

During World War I, Nour agitated against any military alliance between Romania and Russia. He stood out among Germanophiles and local supporters of the Central Powers, agitating in favor of a military offensive into Bessarabia, and demanding the annexation of Transnistria. This combative stance was later overshadowed by revelations that Nour was spying for Russia's intelligence service, the Okhrana.

Still active as an independent socialist in Greater Romania, Alexis Nour won additional fame as an advocate of human rights, land reform, women's suffrage and Jewish emancipation. During the final decade of his life, Nour also debuted as a novelist, but did not register significant success. His late contributions as a Thracologist were received with skepticism by the academic community.

Biography

Early activities

The future journalist, born in Russian-held Bessarabia (the Bessarabia Governorate), was a member of the ethnic Romanian cultural elite, and, reportedly, a graduate of the Bessarabian Orthodox Church Chișinău Theological Seminary.[3][4] According to other sources, he spent his early years in Kyiv and graduated from the Pavlo Galagan College.[2] Nour furthered his studies in other regions of the Russian Empire, where he became a familiar figure to those who opposed Tsarist autocracy, and exchanged ideas with radical young men of various ethnic backgrounds.[4] He is known to have studied Philology at Kyiv University, where he affiliated with the underground Socialist-Revolutionary (Eser) Party, probably infiltrated in its ranks by the Okhrana.[3]

From 1903, Nour was editor of Besarabskaya Zhizn', Bessarabia's "first democratic paper".[5] Nour was still in Bessarabia during the Russian Revolution of 1905, but was mysteriously absent from the follow-up protests by local Romanians (or, in contemporary references, "Moldavians"). According to Onisifor Ghibu (himself an analyst of Bessarabian life), Nour missed out on the chance of establishing a Romanian–Moldavian–Bessarabian "irredentist movement", leading "a mysterious existence", and "not giving even the faintest clue that he was alive, until 1918."[6] In fact, Nour had joined a local section of the Constitutional Democratic (Kadet) Party, the leading force in Russian liberalism. As one historian assesses, this was a maverick's choice: "A. Nour [...] did not consider himself either a socialist or a nationalist."[5]

During the post-revolutionary age of reforms and concessions, when Besarabskaya Zhizn' became a Kadet paper, Nour himself was a member of the Kadet bureau in Bessarabia, and the private assistant of regional party boss Leopold Sitsinski.[2] However, Nour was soon after expelled from the Constitutional Democratic group (reportedly, for having pocketed some of the party's funds) and began frequenting the political clubs of Romanian nationalists.[3]

In 1906, Nour was affiliated with Basarabia, a Romanian-language newspaper for the region's politically minded ethnic Romanians in the region, soon after closed down by Imperial Russian censorship.[7][8] The short-lived periodical, financed by sympathizers from the Kingdom of Romania (including politician Eugeniu Carada), was pushing the envelope on the issue of Romanian emancipation and trans-border brotherhood, beyond what the 1905 regime intended to allow.[9]

In his first-ever article for the review, Alexis Nour suggested that the regional movement for national emancipation still lacked a group of intellectual leaders, or "elected sons", capable of forming a single Romanian faction in the State Duma.[10] Despite such setbacks and the continued spread of illiteracy, Nour contended, Bessarabia's Romanians were more attached to the national ideal, and more politically motivated, than their brethren in Romania-proper.[10] Other Basarabia articles by Nour were vehement rebuttals addressed to Pavel Krushevan, the (supposedly ethnic Romanian) exponent of extreme Russian nationalism.[11]

Viața Basarabiei and 1907 election

The following year, in April, Nour himself launched, sponsored and edited the political weekly Viața Basarabiei, distinguished for having discarded the antiquated Romanian Cyrillic in favor of a Latin alphabet, wishing to make itself accessible to readers in the Kingdom of Romania; an abridged, "people's" version of the gazette was also made available as a supplement, for a purely Bessarabian readership.[12] According to his friend and colleague, Petru Cazacu, Nour had to order the Latin typeface in Bucharest, and used coded language to keep the Russian authorities a step behind him.[13]

As later attested by Bessarabian Romanian activist Pan Halippa (founder, in 1932, of the similarly titled magazine), his predecessor Nour had tried to emulate the Basarabia program of popular education in Romanian, with the ultimate goal of ethnic emancipation.[8] In his capacity as editor in chief, he employed poet Alexei Mateevici, and republished fragments from classical works of Romanian literature.[14] Nour joined Gheorghe V. Madan, publisher of Moldovanul newspaper, in inaugurating the Chișinău-based Orthodox Church printing press, which began publishing a Bessarabian Psalter during spring 1907.[15]

Nour's Viața Basarabiei represented the legalist side of the Bessarabian emancipation movement, to the irritation of more radical Romanian nationalists. Cazacu recalls: "Although moderate, the atmosphere was so stuffed, the hardships so great, the attacks of the right and the left so relentless, that in a short while [this magazine] also succumbed, not without having had its useful effect in the awakening of national sentiment, even among the Moldavians in various parts of Russia, in the Caucasus, and in Siberia."[13] A nationalist historian, Nicolae Iorga, accused Nour of promoting "class fraternity" between the Russians and the Romanians in Bessarabia, citing Nour's explicit rejection of the Russian Revolution.[16] Nour enlisted other negative comments from Iorga when he began writing Bessarabian notices in the Romanian daily Adevărul, which had Jewish proprietors. Iorga, an antisemite, commented: "Mr. Alexe Nour of Chișinău assures us now that his new gazette [...] will not be a philosemitic one".[17] According to Iorga, Nour was given reason to "feel sorry" about the Adevărul collaboration.[18]

Also described as one of the journals whose mission was to popularize the Constitutional Democratic program inside the Bessarabia Governorate,[19] Viața Basarabiei only survived until May 25, 1907, publishing six issues in all.[20] Reportedly, its demise happened on Russian orders, after Nour's editorial line had found itself in conflict with the censorship apparatus.[8] According to Cazacu, the Second Duma election was disastrous for the "Moldavian" intellectuals, who had no journal of their own and were in a state of "despair". The vote in Bessarabia was carried by Krushevan's—pro-Tsarist and far-right—Union of the Russian People (SRN), and by an aristocratic Romanian with centrist views, Dimitrie Krupenski.[21]

By then, Nour had also become regional correspondent for Viața Românească, a magazine published in the Kingdom of Romania by a left-wing group of writers and activists, the Poporanists. From 1907 to 1914, his column Scrisori din Basarabia ("Letters from Bessarabia") was the prime source of Bessarabian news for newspapers on the other side of the Russian border.[2] It mainly informed Romanians on the state of mind and political climate of Bessarabia following the Russian elections.[19] Initially, they describe 1907 Bessarabia with noted regret, as the place where "nothing happens", in contrast with a more politically oriented Romania, where the Peasants' Revolt had seemingly radicalized public opinion.[22] They report with consternation that the official Moldavian Studies Society, had been inactive for an entire year, and concluded that its creation was government farce; however, he also admitted that the bloody events of 1907 Romania were unpalatable for the average Bessarabian.[23]

Nour also questioned the national sentiment of Bessarabia's landowning elite, which had largely been integrated into Russian nobility and served Imperial interests.[22][24] The region's educated classes were Russian-educated, often Russian-oriented, and had therefore lost cheia de la lacătă, care închide sufletul țăranului ("the key that will unlock the peasant's soul").[25] However, in December 1908, he reported with enthusiasm that the Bessarabian Orthodox clergy upheld the use of Romanian ("Moldavian") in its religious schools and press. The measure, Nour noted, gave formal status to the vernacular, in line with his own Viața Basarabiei agenda.[26] Nour's "letters from Bessarabia" irritated the Russifying hierarchs of the Orthodox Church. Seraphim Chichagov, the Archbishop of Chișinău, included him among the Church's "worst enemies", but noted that his Romanian nationalism had managed to contaminate only 20 Bessarabian priests.[27]

Madan scandal and Drug controversy

Nour's other Viața Românească articles unmasked a former colleague, Madan, officially appointed censor of Romanian literature within the Russian Empire, and unofficially a Russian spy in both Bessarabia and Romania.[28] In his reply to Nour, published by the Bucharest political gazette Epoca (September 1909), Madan claimed that his accuser was at once a socialist, an internationalist and a follower of Constantin Stere's Bessarabian separatism.[29] Later research into Special Corps of Gendarmes archives identified Madan as the informant who provided the Imperial authorities with first-hand reports on the perception of Bessarabian issues in Romania, including on Nour's own 1908 article on the Orthodox priests' support for the vernacular.[26] However, the Romanian elite also took distance from Nour, even before 1910. As argued by activist Ion Pelivan, the publicist was living far beyond his means, raising concern that he was receiving payments from the Russian authorities.[3]

Alexis Nour was, between June 1910 and August 1911, the editor of his own press venue, the Russian-language newspaper Bessarabets (which also published a literary supplement).[2][30] The paper had a small circulation, and was entirely financed by the local magnate Vasile Stroescu.[3] Nour's own literary contributions included translations from Russian classics. One such rendition from Leo Tolstoy, dating from 1906, was one of the few Romanian-language books to see print in the Bessarabia Governorate before World War I.[31] Beyond the political notices, Viața Românească published samples of Nour's literary efforts, including memoirs, sketch stories and novellas.[2] He was probably a contributor to the Romanian literary review Noua Revistă Română, possibly the pseudonymous author (initials A. N.) of a 1912 article condemning antisemitism at the Romanian Writers' Society.[32]

When the Bessarabets venture came to an end, Nour was again employed by Besarabskaya Zhizn', before switching to the gazette Drug, representing the controversial Union of the Russian People.[33] Associating with his former adversary, Krushevan, Nour became the editorial secretary, and even joined up with the SRN.[34] With other members of the editorial board, he was soon after involved in a regional press scandal. Nour himself was suspected of having blackmailed centrist leader Krupenski and Roman Doliwa-Dobrowolski, the Marshal of Nobility in Orgeyev. When Doliwa-Dobrowolski sued Drug and the other journalists were rounded up for questioning, Nour fled to Kyiv.[34]

Probably helped along by his Okhrana contacts, he obtained a passport, and exiled himself from Russia.[34] After spending some time in the German Empire, he left for Romania, and, with Constantin Stere's help, enlisted as a student at the University of Iași.[34] He was afterwards seen as a leading member of the Bessarabian expatriate community. According to fellow Bessarabian exile Axinte Frunză, theirs was a minuscule political lobby, with only 6 to 10 active members, all of them saddened by the small-mindedness of Romanian society.[35]

Nour's new series in Viața Românească documents the early spread of Moldovenism. In summer 1914, he informed his readers that the Russian state officials actively persuaded the Bessarabian peasants not to declare themselves Romanian.[36] In this context, he reluctantly admitted, the only hope for a Romanian revival in Bessarabia was for the Romanians to side with the Krupenski-faction conservatives, which, although "hostile to the democratic sentiment of the masses", maintained linguistic purism.[37]

Germanophile press and Transnistrian ethnography

Soon after the outbreak of World War I, Alexis Nour was residing in neutral Romania, active within the Viața Românească circle from his new home in Iași.[38] Like other members of this group (and primarily its founder Stere), he campaigned in favor of rapprochement with the Central Powers, recommending a war on Russia for the recovery of Bessarabia.[39] Nour thought further than his colleagues, speculating about an alliance of interests between Romanians and Ruthenians (Ukrainians). His essay Problema româno-ruteană. O pagină din marea restaurare a națiunilor ("The Romanian-Ruthenian Issue. A Page from the Great Restoration of Nations"), published by Viața Românească in its October–November–December 1914 issue, inaugurated a series of such pieces, which talked about Ukraine's emancipation, the Bessarabian union, and, unusually in this context, the incorporation of Transnistria into Romania (with a new frontier on the Southern Bug).[40]

The latter demand was without precedent in the history of Romanian nationalism,[34] and Nour is even credited with having coined the term Transnistria in modern parlance, alongside the adjective transnistreni ("Transnistrians").[2] Elsewhere, Nour argued that there were over 1 million transnistreni Romanians, a claim which endured as one of the largest, directly above the 800,000 advanced by Bessarabian historian Ștefan Ciobanu.[41] The only larger such estimate came, twenty years after Nour's, from within the Transnistrian community of exiles: ethnographer Nichita Smochină claimed a figure of 1,200,000.[42]

Another one of Nour's analytical texts, titled Din enigma anilor 1914—1915 ("Around the Enigma of 1914—1915"), ventured to state that the German Empire and its allies were poised to win the war, ridiculed the Entente's Gallipoli Campaign, and suggested that a German-led Mitteleuropean federation was in the making.[43] This prognosis also offered a reply to the pro-Entente lobby, who prioritized the annexation of Transylvania and other Romanian-inhabited regions of Austria-Hungary over any national project in Bessarabia. In Nour's interpretation, the German project for Mitteleuropa amounted to the dismemberment of Austria-Hungary, leaving Transylvania free to elect in favor of joining Romania.[44] The notion, also supported by Stere, was hotly contested by Onisifor Ghibu, a Transylvanian. According to Ghibu, the Poporanists seemed to ignore the realities of Austro-Hungarian domination; their ideas about Bessarabian superiority were "provocative", "at the very least rude".[45]

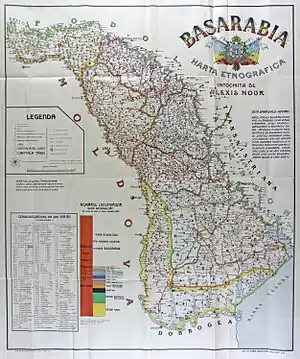

Also in 1915, Nour designed and published in Bucharest an ethnographic map of Bessarabia on a scale of 1:450,000. Building on a cartographic model first used by Zsigmond Bátky in his "Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen" ethnographic map and later adapted to the Balkans by Jovan Cvijić, Nour's map divided the regions depicted into communal entities, represented as pie charts of the various nationalities.[46] The resulting majority (2 out of 3 million inhabitants) was Romanian, with a note explaining that these were known locally as "Moldovans"—being Nour's contribution to the debate on Moldovan ethnicity.[34] Beyond Bessarabia, Nour's map states a claim about the Romanians of Transnistria, including their presence in a locality named Nouroaia.[34]

The pie-chart procedure as a whole was criticized by French geographer Emmanuel de Martonne, who viewed it as inaccurate in rendering the comparative numerical force of the individual populations.[46] Martonne stated having personally verified the accuracy of Nour's map at some point before 1920, and concluded: "Although it is not exempt from all criticism, it is generally as exact as is permitted by the Russian documents on which it bases itself. As is the case with [Bátky's data on the Romanians in] Hungary, one presumes that any error is to the disfavor of Romanians."[47] Bessarabian historian Ion Constantin sees the map as one of Nour's "meritorious" contributions to the cause of Romanian emancipation.[34]

Nour took his ideas outside the Poporanist clubs, and became a contributor to the unofficial Conservative Party press. He became a regular contributor to Petre P. Carp's newspaper pro-Bessarabian and anti-Russian gazette Moldova, which stood by the belief that "Germany is invincible".[48] Nour also expanded on his wartime vision in the Germanophile daily Seara. In 1915, he stated the need for Romania to join the Central Powers' effort of liberating Bessarabia, Ukraine and Poland from Russia, prophesied that Austria-Hungary would inevitably collapse, and depicted future Romania as both a Black Sea and Danubian power.[49] With time, the Bessarabian journalist claimed, the Straits Question would be solved, Romanian rule over Odessa and Constanța would create commercial prosperity, and Romania, a great power, would be entitled to a share of the British, French or Belgian colonial empires.[49] Another of his Seara articles, published in April 1916, argued that German victory in the Battle of Verdun was a matter of days or weeks, after which Europe would be dominated by an "industrious, healthy and conscious, 70 million-strong" German people.[49] Reviewing Nour's project some 90 years later, historian Lucian Boia assessed: "One finds in Nour the drama of the Bessarabian who assesses all things, often in a purely imaginary pitch, around his own ideal of national emancipation."[49]

Wartime refuge and Umanitatea

Against the wishes of Viața Românească Germanophiles, Romania eventually entered the war as an Entente ally, and, in 1917, was invaded by the Central Powers. During these events, Nour was in Iași, where the Romanian government had retreated,[50][51] and whence he made his first contributions to the international press in Entente and neutral countries.[2] He kept company with another Bessarabian agent of the Okhrana, Ilie Cătărău, wanted by the Central Powers on charges of terrorism.[51]

In spring 1917, shortly after the February Revolution toppled the Tsarist regime, Nour's Bessarabian career received full exposure. The committee for exploring the Special Corps of Gendarmes archive made public his reports to the Okhrana, confirming his colleagues' suspicions and exposing Nour to public shame.[34] Nevertheless, the October Revolution and its aftermath seemed to credit Nour's prophecies: although Romania was losing to the Central Powers, the Moldavian Democratic Republic proclaimed by Bessarabian activists looked set to unite with the defeated country. This was noted at the time by the newly appointed Germanophile Premier of Romania, Alexandru Marghiloman, who credited Nour with having helped revise Romanian foreign policy: "[His] map has since been laid out on all tables of the great European conferences, in all chancelleries, and is the soundest document for those who wish to untangle the matter of Bessarabia's nationalities."[2] In April 1918, Nour was again in Chișinău, celebrating the positive vote on Bessarabia's union. This was a risky gesture on his part: present at Londra Restaurant, where Marghiloman was being greeted by the unionist leaders, he was spotted by his former friends, and only rescued from near-certain lynching by the intervention of outgoing MDR Prime Minister, his old colleague Petru Cazacu.[34]

Nour was back in Iași when Romania sued for peace with Germany. Confusion reigned there, with Bolshevik and other Russian troops still parading through the city streets. According to Ghibu, he had an episodic career as private teacher of Russian, having as his clients the neutralized Romanian soldiers and some concerned civilians.[52] On June 24, Nour inaugurated in Iași a new magazine, Umanitatea ("The Human Race" or "The Humanity"), which only published one more issue, on July 14, before closing down.[50]

Umanitatea emphasized Nour's leftist projects for social change, and, according to Lucian Boia, offered a reply to Marghiloman's promise to reform the 1866 constitutional regime.[53] The magazine's agenda called for a three-pronged reform: labor rights in the industrial sphere, the reestablishment of a landed peasantry, and Jewish emancipation.[50] The latter statement of support, Boia notes, was singular "in the context of a quite pronounced Romanian antisemitism", and further emphasized by the presence of Jewish Romanian intellectuals—Isac Ludo, Eugen Relgis, Avram Steuerman-Rodion etc.—among Umanitatea contributors.[50] Boia also notes that the entire Umanitatea program was another sample of Nour's "great projects, quite nebulous and limitless".[50]

Umanitatea was noted for covering, in Nour's own editorials, the developments of Russian political life under the Bolsheviks.[54] The subject of Bolshevik "anarchy" preoccupied him enough to constitute a main topic for his other magazine, the anticommunist Răsăritul ("The East"). Nour's articles, published in Răsăritul and in N. D. Cocea's Chemarea, describe Bessarabia (the "stateless" MDR) as prey to "Bolshevik fury", calling for Romania to immunize itself "against the plague" by simply abandoning hopes to the region. He also revisited his Transnistrian agenda, writing that the Romanian armies needed to move quickly and seize "the people's East, down to the Blue Bug."[52] Ghibu dismissed Nour's new agenda as "enormities", arguing that they show Nour's "bizarre mentality", not unlike that of his revolutionary enemies.[55]

In one of his later essays, Nour attested that his only son, whom the Russian Civil War had caught at Odessa, was a victim of the Soviet Russian-organized shootings of Romanian hostages. According to Nour's account, the young man had died in a mass execution ordered by Commissar Béla Kun, after being made to dig his own grave.[56] Despite such claims of loyalty, Nour is said to have been the focus of official investigation during a clampdown on wartime Germanophiles.[34]

Feminism and Constructivism

During the interwar period, when different political circumstances resulted in the creation of Greater Romania (including both Bessarabia and Transylvania), Nour remained active on the literary and political scene, and was for a while editor in chief of the mainstream literary magazine Convorbiri Literare.[34][56] He also wrote for the newspapers Opinia and Avântul, discussing Russian affairs and Russia's take on "socialist democracy",[57] and was present on the first issue of Moldova de la Nistru, a Bessarabian "magazine written for the people".[58] At Iași, Umanitatea was relaunched in June 1920, but had Relgis as editorial director and Nour as a mere correspondent.[59]

He was still affiliated with the Poporanist periodicals, including Viața Românească and Însemnări Literare, where he mainly published translations from and introductions to Russian literature.[2] By 1925, he was also a contributor to a left-wing literary newspaper based in Bucharest, Adevărul Literar și Artistic.[2][60] In parallel, he worked with C. Zarida Sylva on another Basarabia newspaper, which was dedicated to "national propaganda" in Romania and abroad, and with Alfred Hefter-Hidalgo at Lumea, the "weekly bazaar".[61]

Alexis Nour centered his subsequent activities in the area of human rights defense and pro-feminism. In May 1922, he was one of the Romanian contributors to A. L. Zissu's Jewish daily, Mântuirea.[62] At a time when Romania lacked women's suffrage, he argued that there was an intrinsic link between the two causes: in a piece published by the feminist tribune Acțiunea Feministă, he explained that his struggle was about gaining recognition for "the human rights of women".[63] According to political scientist Oana Băluță, Nour's attitude in this respect was comparable to that of another pro-feminist Romanian writer, Alexandru Vlahuță.[63]

For a while in 1925, Alexis Nour was a supporter of Constructivism and a member of the small but active avant-garde clubs. Writing for M. H. Maxy's Integral magazine (Issue 4), he sought to define the political purpose of Romanian Constructivism: "progress is a gradual adaptation [to the] least reduced division of labor between men. Anything that will slow down that adaptation is immoral, and unjust, and stupid. [...] Herein is the area of social philosophy that forms the foundation of Constructivist integralism."[64]

Final years

In the final part of his career, Nour still carried on with his coverage of Russian politics for Romanians. He published in Adevărul a portrait of liberal White émigré leader Pavel Milyukov.[65] In 1929, having already contributed to the Romanian Red Cross information bulletins, he became one of the original editors of Lumea Medicală, the health and popular science magazine.[66] Nour also signed pieces in Hanul Samariteanului, a literary monthly launched, unsuccessfully, by writers Gala Galaction and Paul Zarifopol.[67] He also turned to fiction writing, completing the novella Masca lui Beethoven ("Beethoven's Mask"), first published by Convorbiri Literare in February 1929.[68]

One of the last projects to involve Nour was a collaborative fiction work, Stafiile dragostei. Romanul celor patru ("The Ghosts of Love. The Novel of the Four"). His co-authors were genre novelists Alexandru Bilciurescu and Sărmanul Klopștock, alongside advice columnist I. Glicsman, better known as Doctor Ygrec. With its speculative undertones, most of which were introduced in the text by Doctor Ygrec,[69] Stafiile dragostei is sometimes described as a parody of science fiction conventions, in line with similar works by Tudor Arghezi or Felix Aderca (see Romanian science fiction).[70] However, Nour's contribution to the narrative only covers its more conventional and less ambitious episodes, which depict the epistolary novel of a sailor, Remus Iunian, and a recluse beauty, Tamara Heraclide—according to literary critic Cornel Ungureanu: "In the 1930s, everyone wrote epistolary novels and sentimental journals, but the worst would have to be those by Mr. Alexis Nour".[69]

In his final years, Alexis Nour had a growing interest in the Prehistory of Southeastern Europe and the proto-Romanian polity of Dacia. The last two of Nour's scholarly works were published posthumously, in 1941, with a Romanian Orthodox Church publishing house, at a time when Romania was ruled by the fascist National Legionary regime. One was specifically dedicated to, and named after, the little-known "cult of Zalmoxis" (Cultul lui Zalmoxis). University of Turin academic Roberto Merlo notes that it formed part of a Zamolxian "fascination" among Romanian men of letters, also found in the research and essays of various others, from Mircea Eliade, Lucian Blaga and Dan Botta to Henric Sanielevici and Theodor Speranția.[71] The other study focused on Paleo-Balkan mythology, and in particular on the supposed contributions of ancient Dacians and Getae to Romanian folklore: Credințe, rituri și superstiții geto-dace ("Gaeto-Dacian Beliefs, Rites and Superstitions"). The book was a co-recipient of the Vasile Pârvan Award, granted by the Romanian Academy.[72] The decision was received with indignation by archeologist Constantin Daicoviciu, who deemed Credințe, rituri și superstiții geto-dace unworthy of attention, as an indiscriminate collection of quotes from "authors good and bad", without any "sound knowledge" of its subject.[72]

According to historiographer Gheorghe G. Bezviconi, Nour died in 1940.[1] He is buried at the Ghencea cemetery in Bucharest.[1]

Notes

- Gheorghe G. Bezviconi, Necropola Capitalei, Nicolae Iorga Institute of History, Bucharest, 1972, p.203

- (in Romanian) Calendar Național 2008. Alte aniversări, National Library of Moldova, Chișinău, 2008, p.455

- Constantin, p.30

- (in Romanian) Pan Halippa, "Unirea Basarabiei cu România" (I) Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, in Literatura și Arta, August 28, 2008, p.8

- Boldur, p.188

- Rotaru, p.261

- Constantin, p.30; Dulschi, p.22-24; Kulikovski & Șcelcikova, p.37; Lăcustă, passim; Rotaru, p.237

- (in Romanian) Ion Șpac, "Pantelimon Halippa – fondator și manager al ziarului și revistei Viața Basarabiei" Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, in Literatura și Arta, November 13, 2008, p.3

- Lăcustă, p.55-56

- Lăcustă, p.56

- Dulschi, p.24

- Kulikovski & Șcelcikova, p.225; Rotaru, p.38-39, 62, 523. See also Boldur, p.193; Cazacu, p.174

- Cazacu, p.174

- Rotaru, p.65

- (in Romanian) "Momente culturale", in Răvașul, Nr. 21-22/1907, p.365 (digitized by the Babeș-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- Rotaru, p.38-39

- Rotaru, p.62

- Rotaru, p.39, 62

- (in Romanian) Mihai Cernencu, Igor Boțan, Evoluția pluripartidismului pe teritoriul Republicii Moldova, ADEPT, Chișinău, 2009, p.66. ISBN 978-9975-61-529-7

- Grossu & Palade, p.225

- Cazacu, p.174-175

- (in Romanian) Catherine Durandin, "Moldova în trei dimensiuni" Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, in Revista Sud-Est, Nr. 2/2007

- Rotaru, p.229, 255

- Rotaru, p.239

- Cazacu, p.175

- Negru, p.75-76

- Nicolae Popovschi, Istoria Bisericii din Basarabia în veacul al XIX-lea subt ruși, Tipografia Eparhială Cartea Românească, Chișinău, 1931, p.472-473

- Negru, p.73, 74

- Negru, p.74

- Kulikovski & Șcelcikova, p.42

- Cazacu, p.175; Silvia Grossu, Gheorghe Palade, "Presa din Basarabia în contextul socio-cultural de la începuturile ei pînă în 1957", in Kulikovski & Șcelcikova, p.15

- (in Romanian) Victor Durnea, "Primii pași ai Societății Scriitorilor Români (II). Problema 'actului de naționalitate' " Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine, in Transilvania, Nr. 12/2005, p.25, 29

- Constantin, p.30-31

- Constantin, p.31

- Rotaru, p.229

- Rotaru, p.249

- Rotaru, p.255

- Boia, p.258; Constantin, p.31

- Boia, p.99-101; Constantin, p.31

- Boia, p.100-101, 258. See also Constantin, p.31

- (in Romanian) N. A. Constantinescu, "Nistrul, fluviu românesc", in Dacia, Nr. 3/1941, p.2 (digitized by the Babeș-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library); P. Pavel, Mircea Popa, "Noi documente privind viața și activitatea lui Iuliu Maniu. Românii de peste hotare. Repartizarea lor în diferite țări" Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, in the December 1 University of Alba Iulia's Annales Universitatis Apulensis. Series Historica, Nr. 2-3/1998-1999, p.48

- Pântea Călin, "The Ethno-demographic Evolution of Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic" [sic], in the Ștefan cel Mare University of Suceava Codrul Cosminului, Nr. 14 (2008), p.176-177

- Boia, p.258

- Boia, p.258-259

- Rotaru, p.257

- Martonne, p.84-86

- Martonne, p.89

- (in Romanian) Ion Agrigoroaiei, "Petre P. Carp și ziarul Moldova" Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, in Revista Română (ASTRA), Nr. 3/2006

- Boia, p.259

- Boia, p.260

- (in Romanian) Radu Petrescu, "Enigma Ilie Cătărău (II)" Archived October 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, in Contrafort, Nr. 7-8/2012

- Rotaru, p.288

- Boia, p.259-260

- Constantinescu-Iași et al., p.65, 93

- Rotaru, p.288, 291-292, 521

- (in Romanian) Lucian Dumbravă, "Constatări amare", in Evenimentul, January 21, 2003

- Constantinescu-Iași et al., p.77, 79, 132

- Desa et al (1987), p.602-603

- Desa et al (1987), p.994

- Desa et al. (2003), p.18; (in Romanian) Mihail Sevastos, "Adevăruri de altădată: Anul Literar 1925", in Adevărul Literar și Artistic, May 24, 2011 (originally published January 3, 1926)

- Desa et al. (2003), p.80, 590

- Desa et al (1987), p.600-601

- (in Romanian) Oana Băluță, "Feminine/feministe. Din mișcarea feministă interbelică", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 233, August 2004

- George Radu Bogdan, "Un modernist: M. H. Maxy", in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Nr. 4/1946, p.869

- Constantinescu-Iași et al., p.19

- Desa et al. (2003), p.591, 787

- Desa et al. (2003), p.491

- (in Romanian) S[evastian] V[oicu], "Mișcarea culturală. Reviste", in Transilvania, Nr. 2/1929, p.158 (digitized by the Babeș-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

- (in Romanian) Cornel Ungureanu, "Mircea Eliade și semnele literaturii", in Luceafărul, Nr. 8/2010

- György Györfi-Deák, "Așa scrieți voi", in Pro-Scris, Nr. 4/2008

- (in Italian) Roberto Merlo, "Dal mediterraneo alla Tracia: spirito europeo e tradizione autoctona nella saggistica di Dan Botta" Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, in the Romanian Academy Philologica Jassyensia, Nr. 2/2006, p.56-57

- (in Romanian) Constantin Daicoviciu, "Însemnări. A. Nour, Credințe și superstiții geto-dace", in Transilvania, Nr. 7-8/1942, p.645-646 (digitized by the Babeș-Bolyai University Transsylvanica Online Library)

References

- Lucian Boia, "Germanofilii". Elita intelectuală românească în anii Primului Război Mondial, Humanitas, Bucharest, 2010. ISBN 978-973-50-2635-6

- Alexandru V. Boldur, Contribuții la studiul istoriei Românilor: Istoria Basarabiei, 3: Sub dominația rusească (1812-1918): Politica, ideologia, administrația, Tiparul Moldovenesc, Chișinău, 1940

- Petru Cazacu, Moldova dintre Prut și Nistru. 1812-1918, Viața Românească, Iași, [n. y.]

- Ion Constantin, "Alexis Nour, agent al Ohranei", in Magazin Istoric, September 2011, p. 30-31

- Petre Constantinescu-Iași, Victor Cheresteșiu, Ludovic Jordáky, Lucrări și publicații din România despre Marea Revoluție Socialistă din Octombrie (1917-1944), Editura Academiei, Bucharest, 1967. OCLC 6271975

- Ileana-Stanca Desa, Dulciu Morărescu, Ioana Patriche, Adriana Raliade, Iliana Sulică, Publicațiile periodice românești (ziare, gazete, reviste). Vol. III: Catalog alfabetic 1919-1924, Editura Academiei, Bucharest, 1987

- Ileana-Stanca Desa, Dulciu Morărescu, Ioana Patriche, Cornelia Luminița Radu, Adriana Raliade, Iliana Sulică, Publicațiile periodice românești (ziare, gazete, reviste). Vol. IV: Catalog alfabetic 1925-1930, Editura Academiei, Bucharest, 2003. ISBN 973-27-0980-4

- (in Romanian) Silvia Dulschi, "Tentative de constituire a organizațiilor și partidelor de orientare națională în Basarabia la înc. sec. al XX-lea", in Administrare Publică, Nr. 2-3/2010, p. 19-26

- (in French) Emmanuel de Martonne, "Essai de carte ethnographique des pays roumains", in Annales de Géographie, Vol. XXIX, Nr. 158, March 15, 1920, p. 84-98 (republished by Persée Scientific Journals)

- (in Romanian) Gheorghe Negru, "Gheorghe Madan – agent al Imperiului Rus", in the University of Bucharest Faculty of Journalism's Revista Română de Jurnalism și Comunicare, Nr.4/2008, p. 69-79

- (in Romanian) Lidia Kulikovski, Margarita Șcelcikova (eds.), Presa basarabeană de la începuturi pînă în anul 1957. Catalog, at the B. P. Hasdeu Municipal Library of Chișinău; retrieved January 26, 2011

- Ioan Lăcustă, "Basarabia, numărul neștiut", in Magazin Istoric, April 2007, p. 55-58

- Florin Rotaru, Basarabia română. Antologie, Editura Semne, Bucharest, 1996. OCLC 38073519