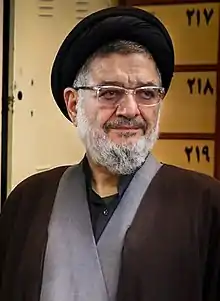

Ali Akbar Mohtashamipur

Ali Akbar Mohtashamipur or Mohtashami (Persian: سید علیاکبر محتشمیپور; 30 August 1947 – 7 June 2021) was an Iranian Shia cleric who was active in the 1979 Iranian Revolution and later became interior minister of the Islamic Republic of Iran.[3] He is "seen as a founder of the Hezbollah movement in Lebanon"[4][5] and one of the "radical elements advocating the export of the revolution," in the Iranian clerical hierarchy.[6]

Ali Akbar Mohtashamipur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 28 October 1985 – 29 August 1989 | |

| President | Ali Khamenei |

| Prime Minister | Mir-Hossein Mousavi |

| Preceded by | Ali Akbar Nategh-Nouri |

| Succeeded by | Abdollah Nouri |

| Member of the Islamic Consultative Assembly | |

| In office 28 May 2000 – 28 May 2004 | |

| Constituency | Tehran, Rey, Shemiranat and Eslamshahr |

| Majority | 717,076 (24.46%)[1] |

| In office 18 February 1989 – 28 May 1992 | |

| Constituency | Tehran, Rey, Shemiranat and Eslamshahr |

| Majority | 225,767 (34.1%)[1] |

| Ambassador of Iran to Syria | |

| In office 1982–1986 | |

| President | Ali Khamenei |

| Prime Minister | Mir-Hossein Mousavi |

| Preceded by | Ali Motazed |

| Succeeded by | Mohammad Hassan Akhtari |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 August 1947 Tehran, Iran |

| Died | 7 June 2021 (aged 73) Tehran, Iran |

| Political party | Association of Combatant Clerics |

| Relatives | Fakhri Mohtashamipour (niece)[2] |

| Alma mater | Alavi Institute Qom Seminary Hawza Najaf |

In an Israeli assassination attempt targeting Mohtashami, he lost his right hand when he opened a book loaded with explosives.[7][8] In June 2021, he died from COVID-19 during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran.[9]

Biography

Mohtashemi studied in the holy city of Najaf Iraq, where he spent considerable time with his mentor Ayatollah Khomeini.[10] During the 1970s he received military training in a Fatah camp in Lebanon and lived in a remote village, Yammoune, in the Beqaa valley.[11] He also accompanied Khomeini during his period in exile in both Iraq and France.[10] He co-founded an armed group in the 1970s with Mohammad Montazeri, son of Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, in Lebanon and Syria, aiming at assisting liberation movements in Muslim countries.[10]

Following the Iranian revolution he served as Iran's ambassador to Syria from 1982 to 1986.[12] He later became Iran's minister of interior. While ambassador to Syria, he is thought to have played a "pivotal role" in the creation of the Lebanese radical Shia organization Hezbollah, working "within the framework of the Department for Islamic Liberation Movements run by the Iranian Pasdaran." Mohtashami "actively supervised" Hezbollah's creation, merging into it existing radical Shi'ite movements; the Lebanese al-Dawa; Islamic Amal; Islamic Jihad Organization; Imam Hussein Suicide Squad, Jundallah and the Association of Muslim Students.[13][14][15] In 1986 his "close supervision" of Hezbollah was cut short when the Office of Islamic Liberation was reassigned to Iran's ministry of foreign affairs.[16] He is also described as having made "liberal" use of the diplomatic pouch as Ambassador, bringing in "crates" of material from Iran.[17] He remained among radical hard line parties even when he was chosen as the minister of the interior in the government of Khomeni.[18]

In 1989[19] the new Iranian president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani ousted Mohtashami from the Lebanon desk of the Iranian ministry of foreign affairs and replaced him with his brother Mahmud Hashemi.[20] This was seen as an indication of Iran's downgrading of its support for Hezbollah and for a revolutionary foreign policy in general.[21]

In August 1991 he regained some of his influence when he became chairman of the defense committee of the Majlis (parliament) of Iran.[22]

More controversially, Mohtashami is thought

to have played an active role, with the Pasdaran and Syrian military intelligence, in the supervision of Hezbollah's suicide bomb attacks against the American embassy in Beirut in April 1983, the American and French contingents of the MNF in October 1983 and the American embassy annex in September 1984,[23][24]

and to have been instrumental in the killing of Lt. Col. William R. Higgins, the American Chief of the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization's (UNTSO) observer group in Lebanon who was taken hostage on 17 February 1988 by Lebanese pro-Iranian Shia radicals. The killing of Higgins is said to have come "from orders issued by Iranian radicals, most notably Mohtashemi," in an effort to prevent "improvement in the U.S.–Iranian relationship."[25] It also came from alleged involvement in the December 1988 bombing of Pan AM Flight 103. The US Defense Intelligence Agency alleges that Ali Akbar Mohtashamipur (Ayatollah Mohtashemi), a member of the Iranian government, paid US$10 million for the bombing:

Ayatollah Mohtashemi: (...) and was the one who paid the same amount to bomb Pan Am Flight 103 in retaliation for the US shoot-down of the Iranian Airbus.[26]

While Mohtashami was a strong opponent of Western influence in the Muslim world and of the existence of the state of Israel,[27] he was also a supporter and advisor of reformist Iranian president Mohammad Khatami who is famous for having championed free expression and civil rights.[28] Mohtashemi was in the Western news again in 2000, not as a hardline radical but for refusing to appear in court in Iran after his pro-reform newspaper, Bayan, was banned.[4]

Behzad Nabavi and Ali Akbar Mohtashami were among those who were prevented by the Guardian council from taking part in the elections of Majlis.[29]

Attempted assassination

In 1984, after the Beirut bombings, Mohtashami received a parcel containing a book on Shia holy places when he was serving as Iranian ambassador to Damascus.[30] As he opened the package it detonated, blowing off his hand and severely wounding him. Mohtashami was medevaced to Europe and survived the blast to continue his work. The identity of the perpetrators of the attack was long unknown,[31] but in 2018 Ronen Bergman, in his book Rise and Kill First, revealed that the Israelis were behind the assassination attempt. The Israeli Prime Minister, Yitzhak Shamir personally signed the assassination order, after being given them by Mossad director Nahum Admoni.[8]

References

- "Parliament members" (in Persian). Iranian Majlis. Archived from the original on 24 October 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "Patriots and Reformists: Behzad Nabavi and Mostafa Tajzadeh". Tehran Bureau. PBS. 11 August 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- Iran: Early Race For Clerical Assembly Gets Bitter Radio Liberty

- Iranian publisher defies court BBC, 26 June 2000

- Barsky, Yehudit (May 2003). "Hizballah" (PDF). The American Jewish Committee. Archived from the original (Terrorism Briefing) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- Ranstorp, Hizb'allah in Lebanon, (1997) pp. 126, 103

- Ali Akbar Mohtashemi explaining story of assassination attempt and how he lost his hand. Iran Negah

- Ronen Bergman, 2018, Rise and Kill First, ch 21

- "Iran cleric who founded Hezbollah, survived book bomb, dies". The Independent. 7 June 2021. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- Sadr, Shahryar (8 July 2010). "How Hezbollah Founder Fell Foul of Iranian Government". IRN (43). Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Hirst, David (2010) Beware of Small States. Lebanon, battleground of the Middle East. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-23741-8 p.177

- Samii, Abbas William (Winter 2008). "A Stable Structure on Shifting Sands: Assessing the Hizbullah-Iran-Syria Relationship" (PDF). Middle East Journal. 62 (1): 32–53. doi:10.3751/62.1.12. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- John L. Esposito, The Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality? Oxford University Press,(1992) pp. 146-151

- Independent, 23 October 1991

- Roger Faligot and Remi Kauffer, Les Maitres Espions, (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1994) pp. 412–13

- Ranstorp, Hizb'allah in Lebanon, (1997) pp. 89–90

- Wright, Sacred Rage, (2001), p. 88

- David Menashri (2001). post revolutionary politics In iran. Frank Cass. p. 48.

- sometime after 17 August

- Nassif Hitti, "Lebanon in Iran's Foreign Policy: Opportunities and Constraints," in Hosshang Amirahmadi and Nader Entessar Iran and the Modern World, Macmillan, (1993), p. 188

- Ranstorp, Hizb'allah in Lebanon, (1997) p. 104

- Ranstorp, Hizb'allah in Lebanon, (1997), p. 106

- Foreign Report, 20 June 1985

- New York Times, 2 November 1983; and 5 October 1984

- Ranstorp, Hizb'allah, (1997), p. 146

- "PAN AM Flight 103" (PDF). Defense Intelligence Agency, DOI 910200, page 49/50 (Pages 7 and 8 in PDF document, see also p. 111ff). Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ""Iran opens 'largest' conference on Palestinian intifada"". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2006.

- "Reformist newspaper closed in Iran", BBC News, 25 June 2000

- Anoushiravan Enteshami & Mahjoob Zweiri (2007). Iran and the rise of Neoconsevatives, the politics of Tehran's silent Revolution. I.B.Tauris. p. 9.

- Javedanfar, Meir (24 November 2009). "Hezbollah's Man in Iran". Frontline. PBS. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- Wright, Sacred Rage, (2001), p. 89

- "Iran cleric who founded Hezbollah, survived book bomb, dies". New Haven Register. 7 June 2021. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

Bibliography

- Ranstorp, Magnus, Hizb'allah in Lebanon : The Politics of the Western Hostage Crisis, New York, St. Martins Press, 1997

- Wright, Robin, Sacred Rage, Simon and Schuster, 2001

External links

Media related to Ali Akbar Mohtashamipur at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ali Akbar Mohtashamipur at Wikimedia Commons- Tehran, Washington, and Terror: No Agreemnt to Differ

- Analysis: Iran Sends Terror-Group Supporters To Arafat's Funeral Procession 12 November 2004

- How Hezbollah Founder Fell Foul of Iranian Regime 8 July 2010