Allen Butler Talcott

Allen Butler Talcott (April 8, 1867 – June 1, 1908) was an American landscape painter. After studying art in Paris for three years at Académie Julian, he returned to the United States, becoming one of the first members of the Old Lyme Art Colony in Connecticut. His paintings, usually landscapes depicting the local scenery and often executed en plein air, were generally Barbizon and Tonalist, sometimes incorporating elements of Impressionism. He was especially known and respected for his paintings of trees. After eight summers at Old Lyme, he died there at the age of 41.

Early life and education

Allen Butler Talcott was born on April 8, 1867, in Hartford, Connecticut,[1] into an established and prominent New England family. His artistic inclinations were apparent at an early age, as he created sketches of teachers and fellow students in the margins of his grade school books.[2]

He attended Trinity College in Hartford, receiving a diploma in 1890.[1] While there, he was a member of the Fraternity of Delta Psi (St. Anthony Hall).[3] His formal art education began at the Hartford Art Society, where he studied with painter Dwight William Tryon.[4] He moved to Manhattan while he studied for a short time at the Art Students League of New York. Then he attended Académie Julian in Paris for three years, studying under Jean-Paul Laurens and Benjamin Constant.[5] His work received its first artistic recognition during this period in France, as his paintings were exhibited at the 1893 and 1894 Paris Salons.[6]

Work

Talcott lived in Arles in 1897, renting Vincent van Gogh's house, along with Frank DuMond.[5] He came home to Hartford, where he set up a studio, which he maintained for a few years.[6] He also returned to New York, joining a cooperative studio complex which had been established by Henry Ward Ranger. Ranger became friends with Talcott, as well as an influence.[2] Ranger was also founder of the Old Lyme Art Colony in Connecticut,[5] and Talcott became one of the first artists to join.[4] When he first arrived in 1901, he stayed at Florence Griswold's boarding house,[6] which would later be turned into an art museum. He worked in his New York City studio during the winters,[4] and spent his summers at Old Lyme for eight years, until his death there in 1908.[2]

Barbizon art was popular with artists in the U.S. during this period. Among Ranger and other Old Lyme artists, a variant, Tonalism, evolved in which the palette consisted of just a few muted colors.[7] Talcott had gained a fondness for French Impressionism and was exposed to its American equivalent at Cos Cob, Connecticut, in the late 1890s. There, artists such as Childe Hassam and John Henry Twachtman were developing the artistic style.[7] But Ranger and Tryon were stronger influences on Talcott, and his early paintings are primarily Barbizon and Tonalist[6] – landscapes in shades of brown, green and gold.[2]

Talcott bought an Old Lyme estate looking out upon the Connecticut River in 1903.[6] Around this time, Hassam was bringing Impressionism to the colony, and many of the artists including Talcott began moving in that direction.[5] He did not, however, fully adopt the principles of Impressionism, instead integrating certain aspects into his Tonalist paintings.[7] He retained the Tonalist interest in a unified set of colors, while incorporating the Impressionist concentration on the effects of light by lightening his palette.[4] While lighter than Ranger's, Talcott's colors were still subdued compared to those of the Impressionists.[7] The nature of his brushstrokes also changed, becoming more "flickery". In addition to Hassam, DuMond also influenced him artistically.[2]

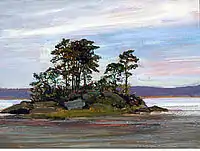

Although he created some portraits, for example, of family members,[8] his subject matter consisted primarily of landscapes, often depicting scenes in and around Old Lyme and along the Connecticut River. He was particularly fond of painting trees, and was known and respected for those paintings.[2][4] Charles Vezin, another artist in the colony, said of Talcott: "He loved and keenly appreciated nature, and his knowledge of all its phases was unusual.... His fellows conceded that no one was his peer in the knowledge of trees and how to paint them."[2] Talcott liked to work en plein air, creating oil sketches which he painted on wood panels. These sketches were often of high enough quality that they could be regarded as finished paintings,[2] and were "admired for their sense of immediacy and rich textures."[9]

In a review of a 1991 show of Talcott's work at the Mattatuck Museum, The New York Times critic said that Talcott was "more talented than many of his contemporaries who went on to Impressionist fame".[5]

Personal life

In 1905, Allen married Katherine Nash Agnew, daughter of New York physician Cornelius Rea Agnew, and they had a son, Agnew.[1][2] Talcott's uncles, John Butler Talcott and James Talcott who together had established the American Hosiery Company, were both patrons of his work and John was the founder, through a large endowment made in 1903, of the New Britain Museum of American Art that has several of Talcott's paintings in their collection.[5][8]

Allen Butler Talcott's nephew was also an artist, American sculptor, author, and illustrator Dudley Talcott.

Talcott died at his Old Lyme summer home on June 1, 1908, of a heart attack; he was 41 years old.[1][2]

Exhibitions and collections

Talcott's landscapes were the subject of a single solo show during his lifetime, at Kraushaar Galleries in 1907; a review in The New York Times noted Talcott's ability to combine "an uncommon sense of the structure and underlying skeleton of a landscape with a feeling for color."[10] Talcott exhibited regularly at various venues including the National Academy of Design, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Society of American Artists, Wadsworth Atheneum, the Carnegie Institute, and the Old Lyme library, as well as other salons. Talcott was awarded a silver medal in 1904 at the St. Louis Exposition.[5][6][11] He also won a medal at the Portland Exposition.[1] As part of its eightieth anniversary celebration in 1983, the New Britain Museum of American Art featured an exhibition of Talcott landscapes.[5]

His work is in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[12] the Florence Griswold Museum,[13] the Mattatuck Museum,[4] the New Britain Museum of American Art, the Lyman Allyn Art Museum, and the Worcester Art Museum.[14] Talcott was a member of the Salmagundi Club and the Lotos Club, and has work included in the collection of the latter.[1]

Gallery

Evening

Evening Oak Tree and Marshland, left panel detail

Oak Tree and Marshland, left panel detail Oak Tree and Marshland, right panel detail

Oak Tree and Marshland, right panel detail Path Through the Woods

Path Through the Woods Spreading Oak

Spreading Oak The Bright Light of Autumn

The Bright Light of Autumn

References

- "Obituary". American Art News. 6 (31): 4. June 13, 1908. JSTOR 25590354.

- "Allen Butler Talcott". Florence Griswold Museum. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "Catalogue of the members of the fraternity of Delta Psi - 1912". www.familysearch.org. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- "Evening". Mattatuck Museum. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- Raynor, Vivien (November 3, 1991). "Mattatuck Offering 'The Poetry Of Light'". The New York Times. p. 20. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "Allen Butler Talcott". Florence Griswold Museum. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "Oak Tree and Marshland". Florence Griswold Museum. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "Old Lyme Welcomes Talcott Exhibit". The Day. New London, Connecticut. June 20, 1983. p. 10. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- Riback, Estelle. Henry Ward Ranger: Modulator of Harmonious Color, 22–23. Fort Bragg, California, Lost Coast Press, 2000. ISBN 1-882897-48-X

- Newman, Joseph F. Allen Butler Talcott: A Life Unfinished, 1, 12. The Cooley Gallery, exhibition catalogue, 2008.

- "Old Lyme Welcomes Talcott Exhibit". The Day. New London, Connecticut. June 20, 1983. p. 11. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "Return of the Redwing". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "Collection search: Allen Butler Talcott". Florence Griswold Museum. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "Search Results: Talcott, Allen Butler". Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved July 23, 2013.