Alois Rašín

Alois Rašín (18 October 1867 in Nechanice,[1] Bohemia, Austria-Hungary – 18 February 1923 in Prague,[2] Bohemia, Czechoslovakia) was a Czech and Czechoslovakian politician, economist, one of the founders of Czechoslovakia and first Ministry for Finance. He was the author of the first law of Czechoslovakia and creator of the country's currency, the Czechoslovak koruna. Rašín was a representative of conservative liberalism and was mortally wounded in assassination for being viewed as a head of the nation's capitalism.[3]

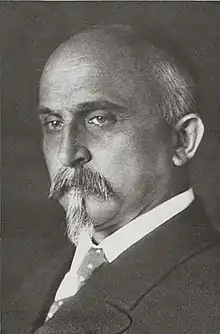

Alois Rašín | |

|---|---|

Rašín, c. 1918 | |

| Member of Imperial Council | |

| In office 1911–1917 | |

| Member of Revolutionary National Assembly | |

| In office 1918–1920 | |

| 1st Minister for Finance of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 14 November 1918 – 8 July 1919 | |

| President | Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk |

| Prime Minister | Karel Kramář |

| Succeeded by | Cyril Horáček |

| Member of National Assembly of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 1920–1923 | |

| 7th Minister for Finance of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 7 October 1922 – 18 February 1923 | |

| President | Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk |

| Prime Minister | Antonín Švehla |

| Preceded by | Augustin Novák |

| Succeeded by | Bohdan Bečka |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 October 1867 Nechanice, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 18 February 1923 (aged 55) Prague, Bohemia, Czechoslovakia |

| Cause of death | the consequences of the assassination |

| Resting place | Dejvice Prague Bohemia Czech Republic |

| Nationality | Czech |

| Political party | Czech Statutory Party Young Czech Party Czech Statutory Democracy Czechoslovak National Democracy |

| Spouse | Karla Jánská |

| Children | Ladislav Rašín Miroslav Rašín Ludmila Rašínová |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Charles University |

| Occupation | lawyer, politician, journalist, economist |

Early years

Rašín was born as a ninth child (of which seven were alive) into the cottage in the outskirts of a small town Nechanice near Hradec Králové. His father František Rašín was a farmer, baker and a vendor of flour and cereals. His mother worked in their household and on the field. The family later bought a house in the town and another field. Later in life, Rašín described poor social reality in the area that was focused on the sugar industry.[4] He also criticized the so-called "harfenictví": traveling musician groups connected to prostitution that expanded after the cancellation of the corvee.[3]

From 1878 to 1881, Rašín attended a gymnasium in Nový Bydžov and he spent the fourth year of the gymnasium in a German gymnasium in Broumov. He finished the last years of high school in the gymnasium of Hradec Králové and graduated there in 1886. In these years he became interested in politics into which he was guided by his father who in 1887 became the mayor of Nechanice. He was fourth of his brothers who started to study at university. The other two brothers pursued a job in the trade sector. Firstly, he studied at the Faculty of Medicine of Charles University (back then called Charles-Ferdinand) but he was forced to leave due to lung disease. He switched for Faculty of Law because there was an optional attendance[5] at lectures and moved to the house of his sister in Krkonoše for rehabilitation. After two years he recuperated.[3]

Student radical movement

In 1888, Rašín returned to Prague to properly continue his studies. There he was actively participating in the student movement and three years later he participated at the Conference of Slavonic students with Antonín Hajn and Václav Klofáč. The Czech youth's opinions defied against the Austrian monarchy, police and the conservative Old Czech Party. Their most powerful instrument was the Magazine of Czech Students (Czech: Časopis českého studentstva), where they propagated the adoption of universal voting rights and greater national rights for Czech people. Rašín was supporting the National Freedom Party which is another name for the Young Czech Party that got into the Bohemian Diet and in 1891 into the Imperial Council.[3]

In October 1891, he graduated from his law studies at Charles University and continued in his political activity. In the day of the Emperor's Franz Joseph I of Austria arrival to Prague, Rašín published an anti-state legal-political text Czech State Law (Czech: České státní právo) in which he outlined the program of restoring the independent Czech state in the spirit of the democracy with the guarantees for the rights of the minorities. He joined service in the military in Hungarian Pest (where he was complaining about their cuisine[4]) and passed an officer’s exams with the best results. But because of his previous controversial article that was confiscated by the police, he was threatened by prolonging his service in the military to two years in total and loss of his ranks.[3]

Rašín returned from his military service in the fall of 1892 and started to work as an advocate concipient. He was elected the mayor of "Slavia": literary and rhetorical association of progressors that supported strengthening radicalism. He also published critical articles in journals New Flows of Ideas (Czech: Nové Proudy) and Prospects (Czech: Rozhledy) like Study on the death penalty, Judicial independence, Political crimes according to the outline of the new Criminal Code, Reflections on the draft Criminal Code.[3]

Despite having little and questionable evidence against radical movements in Prague, the Austrian government declared a state of emergency in September 1893 and started to arrest critical voices.[6] In October Alois Rašín was taken to custody together with redactors and editorial staff of oppositional newspapers Antonín Hajn, Josef Škába, Antonín Pravoslav Veselý, Karel Stanislav Sokol, Stanislav Kostka Neumann, and others. Journals were banned and 70 people were arrested. The defendants in the process remembered as Omladina Trial were accused of the highest treason for conspiring against the state. In fact, the group called Omladina never existed. In January 1894 the trial began and Rašín was sentenced to 2 years unconditionally to prison in Bory (cell number 248). He lost his academic titles and civil rights.[3]

In prison, he never asked for pardon and in his free time, he pursued learning French, English, reading, translating (translated English social-political text The Eight Hour Day), and studying national economic policies. In November 1894, his father became a member of the Imperial Council which is the highest legislative body of the Cisleithanian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire based in Vienna. When he returned, he planned to stand against weakness and humanism of the realist wing of the Young Czech Party represented by Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.[4] The Young Czech Party was also denounced by supporters of Czech Modernism like Josef Svatopluk Machar.[3]

Political activity after the amnesty

Rašín left prison after the amnesty in November 1895 and regain his academic titles. He returned to writing his critical anti-monarchic articles to Radical Newspaper, newly with a critique of Masaryk’s views. The Czech Progressive Movement divided to radically progressive around the journal Independence (Czech: Samostatnost) and Antonín Hajn and to nationally progressive and statutory around Radical Newspaper which Rašín turned into a journal. In 1899, he was partially involved in the creation of a Radical Statutory Party officially named Czech Statutory Party (Czech: Česká státoprávní strana) but left it year after when his son was born. He founded independent weekly newspaper Word (Czech: Slovo) and created his own Law Office. As an advocate, Alois Rašín represented Živnobanka bank.[3]

The weekly paper ended 1905 and together with the banker of Živnobanka Jan Preiss, Rašín entered in 1907 into the Young Czech Party, the second biggest burgheral party after agrarian. He was propagating universal suffrage and was trying to reform the party. Rašín was the first in Czech lands who introduced member legitimations, regional branch offices, paid regional secretary and party cash register with regular contributions. He sided with Karel Kramář and František Fiedler and founded Party’s journal Day (Czech: Den). With Kramář he gained Czech newspapers National Newspaper in 1910. Rašín, new editor-in-chief, Preiss and Antonín Pimper were writing about economic policy. In elections 1911 to Bohemian Diet, they were second after social democrats and he also got into Imperial Council as a member for the district Bohemia 31 – Klatovy. He joined Council’s Czech Club. In 1914 he published text Political Crimes (Czech: Politické zločiny) dealing with jurisdiction, consequences of punishment and imprisonment of political prisoners.[3]

Resistance during the First World War

After the start of the Great War, Rašín sided with the anti-monarchy voices in the country but realized that parliament parties don’t matter anymore. Přemysl Šámal together with Edvard Beneš, Karel Kramář, Václav Klofáč, Alois Rašín and later Antonín Švehla created a resistance group Maffia,[7] inspired by Sicilian Mafia. They created the so-called National Council (Czech: Národní rada) that financed foreign resistance led by Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.[8] The consequences got to them in July 1916 when Rašín was arrested, taken into custody in Vienna and charged for treason and espionage. The process with Alois Rašín, Karel Kramář, journalist and translator Vincenc Červinka, and accountant of the malt house Zdeněk Zamazal lasted from December 1915 to July 1916 with the result of the death penalty.[9] Later in the same year, Emperor Franz Joseph I and after him, Charles I died, and punishments were changed to 10 years in Austrian Möllersdorf. Alois Rašín shared a cell with Karel Kramář. During the time in the prison, Rašín wrote text National Economy (Czech: Národní hospodářství), which was published later in 1921. His Imperial Council Member’s mandate was taken away from him in June 1917. Next month, the amnesty was announced.[3]

After his return from prison, viewed as a national hero, he immediately started to be politically active.[6] He regained his Doctor of Laws academic title (JUDr.). In 1918, the Young Czech Party merged with the Statutory Progressive Party, Moravian People's Progressive Party and some part of the Progressive Party (Realists) with the common name the Czech Statutory Democracy. The Old Czech Party joined in the next year. As a party chairman was elected Karel Kramář. Rašín was part of the party’s leadership that set its goals: support of social justice but rejection of the socialism as such, support of Czech nationalism and democracy, the need for strong control state, police, army and the large state apparatus. It promoted secularization, but with the preservation of freedom of religion and a strong influence of Christian morality, it also promoted solidarity and education.[10] It was supposed to be oriented on the United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Czarist Russia. The National Newspaper continued to be the party’s newspapers.[3]

Independent Czechoslovakia

In July 1918, the National Committee of Czechoslovakia (Czech: Národní výbor československý) was formed to overtake the power in the country and to create new laws. Karel Kramář was Chairman, Antonín Švehla Vice-Chairman, František Soukup Managing Director and Alois Rašín Member of the Board. In the night from 27th to 28th, Vlastimil Tusar called Rašín from Vienna and said that Czech politics needs to go to the front and support fighters in endurance and not leaving. He knew that this is a sign of surrender. Rašín said: “I was convinced that it will burst tomorrow.” [11] In the morning, Rašín met Švehla and others from the National Assembly. After they received Andrássyho nóta (recognition of nations to self-determination), they decided to take the power before surrender. Today, Alois Rašín is remembered as one of the Men of the 28th October (with Antonín Švehla, Jiří Stříbrný, Vavro Šrobár, František Soukup), who together declared an independent Czechoslovakian state. Rašín was the first one who publicly announced the state in the place of National Assembly, he also was the author of the first law which established an independent state.[3]

In November 1918, the Revolutionary National Assembly was formed. On the first meeting, the members elected Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk as the President of the Republic and appointed Karel Kramář Prime Minister. Alois Rašín was firstly supposed to be the Interior Minister but for his knowledge in economics, he was needed to take the Ministry of Finance because state finances were devastated by inflation. Journalist Ferdinand Peroutka pointed out that Rašín was not a pure economist but he has more political experience than for example Rašín’s opponent doctor Karel Engliš. January 1919, Alois Rašín wrote to Edvard Beneš: "The population thinks that freedom means not paying taxes, no one is doing anything from executions, so I don't know how economics could be managed further," but at the same time state is relied on as on the solver of all problems.[11]

As a Minister for Finance, Alois Rašín had efforts to back his proposed currency by gold. For that, he announced nationwide voluntary collection, where 64 kilograms of pure gold was obtained. At the beginning of 1919, Rašín closed borders and the isolated whole country from 26 February to 9 March and started to stamp all money from which he withholds some part as a government loan.[11] For that 2 weeks, he was given rule over police and army. The goal was to disconnect currencies, lower volume of money in circulation and subordinate emission policy to a newly created state bank. After the left won the elections in 1919, Vlastimil Tusar was appointed Prime Minister and Rašín became only Member of the Parliament.[12]

The second Vladimír Tusar’s government was established in 1920 after the Constitution of Czechoslovakia was approved. Rašín still got a mandate for Czechoslovakian National Democracy that was also part of the Committee of Five (Czech: Pětka). In the same year, Alois Rašín published his book My Finance Plan (Czech: Můj finanční plán) describing Czechoslovakian financial history from Austria-Hungary till present days. Two years later he followed up with publications Financial and Economic Policy until the End of 1921 (Czech: Finanční a hospodářská politika do konce roku 1921), and Inflation and Deflation (Czech: Inflace a deflace). He was appointed Ministry for Finance in the government of Antonín Švehla and introduced many measures against social benefits. He also criticized monetary compensations for the legionaries. Amidst an economic crisis, Rašín stressed the politics of deflation (in 1922 prices dropped by 42%, salaries by 32%) and a strong currency.[13] High unemployment caused great animosity towards him, especially from the left. A fierce anti-Rašín campaign developed.[9]

Assassination

In his last days of politics, Rašín got into conflict with his colleagues about deflationary measures. President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk was planning to remove Alois Rašín from office. In the morning of 5 January 1923, Alois Rašín came out of his apartment in Žitná street house number 8 and was shot in the back and side[14] when trying to get in the ministry car. He died after a long period of suffering on 18 February 1923. The assassin was young anarcho-communist Josef Šoupal who confessed and told that he was planning to kill other representatives of Czechoslovak capitalism Jaroslav Preiss and Karel Kramář. Because he was younger than 21 years, he wasn’t sentenced to death but imprisoned for 18 years in Kartouz.[15] The assassination was condemned by the president and many anti-socialist laws were introduced.

Relations

Rašín married Karla Janská[16] from Prague’s Smíchov in 1899. His wife’s brother Jan Janský was the discoverer of blood groups. Alois Rašín had three children with his wife Karla: Ladislav (1900), Miroslav (1901) and Ludmila (1904). His son Ladislav continued in his father’s footsteps as a politician. He was part of the resistance against the Nazis. Gestapo arrested him in 1938. He died in a prison in Nazi Germany a few days before the American troops came.[17]

Characteristics

According to Ferdinand Peroutka, Alois Rašín was a thrifty man and as the Minister of Finance was very cautious every time someone demanded some portion of the governmental budget. He was a workaholic and demanded the same from those around him.[4] He also had an uncompromising and hot-headed nature. At a time when the Germans demanded greater autonomy he stuck out his tongue and called them monkeys. Rašín lived ascetic life avoiding any dance or sport.[3] Alois Rašín was also member of freemason Lodge in Prague.[18]

Publications

- České státní právo, Ed.: Časopis českého studenstva, Prague 1891 (this brochure was forbidden)

- Můj finanční plán, Pražská akciová tiskárna, Prague 1920

- Listy z vězení, Prague 1937

- Mé vzpomínky z mládí, Prague 1928

- Financial Policy of Czechoslovakia during the First Year of its History, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1923 (online at Archive.org)

- Finanční a hospodářská politika do konce roku 1921, Pražská akciová tiskárna, Prague 1922

- Národní hospodářství, Český čtenář, Prague 1922

- Die Finanz- und Wirtschaftspolitik der Tschechoslowakei, Duncker & Humblot, Munich/Leipzig 1923

Further reading

- Alois Rašín – Dramatický život českého politika by Čechurová Jana, Prague 1997

- Alois Rašín – Jeho život, dílo a doba by Hoch Karel, Prague 1934

- Říjen 1918 by Klimek Antonín, Prague 1998

- Paměti dr. Aloise Rašína (editor Ladislav Rašín), Brno 1994

- Dr. Alois Rašín – Úvahy a vzpomínky by Penížek Josef, Prague 1926

- Rašínův památník (editors F. Fousek, J. Penížek, A. Pimper), Prague 1927

- Alois Rašín by Vencovský František, Prague 1992

References

- "Registry Office Nechanice, 1857-1878, page 136, image 141" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Archive of the Prague capital, Death Registry POD Z5 • 1915-1923, p. 186. Available online.

- , Česká televize - Alois Rašín, 2019-12-08 (in Czech)

- Rašín, Alois, 1867-1923. (1994). Paměti Dr. Aloise Rašína. Rašín, Ladislav, 1900-1945. (2. vyd ed.). Brno: Bonus A. ISBN 80-901693-4-1. OCLC 32001757.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mé vzpomínky z mládí, Rašín Alois, Prague 1928

- Šetřilová, Jana. (1997). Alois Rašín : dramatický život českého politika (Vyd. 1 ed.). Praha: Argo. ISBN 80-7203-061-2. OCLC 38233912.

- Pacner, Karel (2012). Osudové okamžiky Československa (in Czech). Praha: Nakladatelství BRÁNA. ISBN 978-80-7243-597-5.

- PRECLÍK, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), 219 str., book first issue, Karvinná: Paris ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (in association with the Masaryk´s democratic movemnt, Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3. Str. 8-48; 95-116; 125-148; 157-162; 165-169

- Hoch, Karel, 1884- (1934). Alois Rašín, jeho život, dílo a doba. Orbis. OCLC 9854236.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dr. Alois Rašín – Úvahy a vzpomínky by Penížek Josef, Prague 1926

- Kosatík, Pavel. (2010). Čeští demokraté : 50 nejvýznamnějších osobností veřejného života (Vyd. 1 ed.). Praha: Mladá fronta. ISBN 978-80-204-2307-8. OCLC 711170744.

- "Poslanecká sněmovna Parlamentu České republiky - jmenný rejstřík" (in Czech). Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Koderová et al., Teorie peněz(In Czech)

- Ferdinand Peroutka: Budování státu. Lidové noviny 1991.(In Czech)

- Borovička V. P.: Atentáty, které měly změnit svět. Svoboda 1975. s. 179. (In Czech)

- Marriage Registry Record Available online.

- , Česká televize - Ladislav Rašín, 2019-12-08 (in Czech)

- Sadilek, Jacob. "Czechoslovakia: a Masonic wonder?". Praga Masonica. Retrieved 9 September 2023.