Alternative formats

Alternative formats include audio, braille, electronic or large print versions of standard print such as educational material, textbooks, information leaflets, and even people's personal bills and letters. Alternative formats are created to help people who are blind or visually impaired to gain access to information either by sight (large print), by hearing (audio) or by touch (braille).

Audio

Audio information can be used by anyone who owns a CD player, a DAISY player or a computer. Audio enables people who are blind or visually impaired to access information through hearing, in the sense that print readers would understand it.

Choosing audio

Individuals are likely to have their own preferences about the way they access audio, depending on their experiences, how comfortable are they with technology, and the equipment they use to access the audio content.

CD as a medium for accessing information

compact discs (CDs) were first produced in the 1980s to store and playback sound recordings exclusively, and became superior to cassette tapes (AC) offering better sound and larger storage space. Standard CDs have a diameter of 120 millimeters (4.7 in) and can hold up to 80 minutes of uncompressed audio (or 700 Megabytes of data). CDs offer navigation options from the beginning of one track to another, rather than having to fast forward or rewind as with cassettes.

Over time, CDs have progressed from being solely for audio, to being a format for different kinds of data storage, such as text, images, photos and videos. Educators can use CDs to store educational materials including taped lectures, presentations, and handouts into one compact disc for the student to access on CD players or computers.

Audio description

Under the Twenty-First Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act of 2010, audio descriptions of visual information must be provided for media originally aired on television, streaming services and online games. Audio description is often difficult for blind people to use and experiences attempting to access audio descriptions are often unsatisfactory, with, for example, many DVDs being inaccessible.[1]

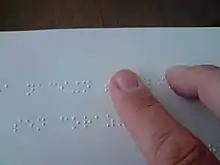

Braille

Braille is a tactile system of raised dots that enables people who are visual impaired or blind to access information by touch. The pattern of raised dots is arranged in cells of up to six dots, creating a total of 63 different combinations possible. Each cell represents an alphabet letter, numeral, or punctuation mark. Some frequently used words and letter combinations also have their own single cell patterns.

Braille can be the building block for language skills and a way to teach spelling, grammar, and punctuation to people with vision loss or who are deaf-blind. Braille codes represent alphabets, denote numbers, symbols, music and mathematical notations. Braille books are available in all subject areas, ranging from modern fiction to mathematics, music and law. As with printed text, Braille makes it possible for people to access information in this format.

Electronic (e-text)

Technology allows people to do research online, share documents via email, and download lecture notes from school websites. With written text converted into a format that is readable on the computer, it can be accessed visually with screen magnification software, or through auditory means with text-to-speech technology.

Large print

Large print is essential for people who have visual or learning difficulties and have trouble reading fine print or deciphering crowded text at one time. Large print usually ranges from 16 to 22 point, while giant print uses fonts that are bigger than 24 point.

Research has demonstrated the positive impacts of providing enlarged font size for people with mild to moderate visual impairments, resulting in an increased reading fluency and speed.[2]

References

- Jordan, Philipp; Oppegaard, Brett (2018). "Media Accessibility Policy in Theory and Reality: Empirical Outreach to Audio Description Users in the United States". arXiv:1809.05585 [cs.HC].

- Fuchs, Jöerg (2008). "Influence of font sizes on the readability and comprehensibility of package inserts". Pharmazeutische Industrie. 70 (5): 584–592.