Alodia

Alodia, also known as Alwa (Greek: Aρουα, Aroua;[3] Arabic: علوة, ʿAlwa), was a medieval kingdom in what is now central and southern Sudan. Its capital was the city of Soba, located near modern-day Khartoum at the confluence of the Blue and White Nile rivers.

Alodia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th century–c. 1500 | |||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Possible flag according to the Catalan Atlas of 1375 | |||||||||||||

Estimated extent of Alodia in the 10th century | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Soba | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Nubian Meroitic(Possibly still spoken) Greek (liturgical) Others[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Coptic Orthodox Christianity Traditional African religion | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||

• First mentioned | 6th century | ||||||||||||

• Destroyed | c. 1500 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Sudan Eritrea | ||||||||||||

Founded sometime after the ancient Kingdom of Kush fell, around 350 AD, Alodia is first mentioned in historical records in 569. It was the last of the three Nubian kingdoms to convert to Christianity in 580, following Nobadia and Makuria. It possibly reached its peak during the 9th–12th centuries when records show that it exceeded its northern neighbor, Makuria, with which it maintained close dynastic ties, in size, military power and economic prosperity. Being a large, multicultural state, Alodia was administered by a powerful king and provincial governors appointed by him. The capital Soba, described as a town of "extensive dwellings and churches full of gold and gardens",[4] prospered as a trading hub. Goods arrived from Makuria, the Middle East, western Africa, India and even China. Literacy in both Nubian and Greek flourished.

From the 12th, and especially the 13th century, Alodia was declining, possibly because of invasions from the south, droughts and a shift of trade routes. In the 14th century, the country might have been ravaged by the plague, while Arab tribes began to migrate into the Upper Nile valley. By around 1500 Soba had fallen to either Arabs or the Funj. This likely marked the end of Alodia, although some Sudanese oral traditions claimed that it survived in the form of the Kingdom of Fazughli within the Ethiopian–Sudanese borderlands. After the destruction of Soba, the Funj established the Sultanate of Sennar, ushering in a period of Islamization and Arabization.

Sources

.jpg.webp)

Alodia is by far the least studied of the three medieval Nubian kingdoms,[5] hence evidence is very slim.[6] Most of what is known about it comes from a handful of medieval Arabic historians. The most important of these are the Islamic geographers al-Yaqubi (9th century), Ibn Hawqal and al-Aswani (10th century), who both visited the country, and the Copt Abu al-Makarim[7] (12th century).[8] The events around the Christianization of the kingdom in the 6th century were described by the contemporary bishop John of Ephesus;[9] various post-medieval Sudanese sources address its fall.[10][11] Al-Aswani noted that he interacted with a Nubian historian who was "well-acquainted with the country of Alwa",[12] but no medieval Nubian historiographical work has yet been discovered.[13]

While many Alodian sites are known,[14] only the capital Soba has been extensively excavated.[15] Parts of this site were unearthed in the early 1950s, further excavations taking place in the 1980s and 1990s.[16] A new multidisciplinary research project was scheduled to start in late 2019.[17] Soba is approximately 2.75 km2 (1.06 sq mi) in size and is covered with numerous mounds of brick rubble previously belonging to monumental structures.[16] Discoveries made so far include several churches, a palace, cemeteries and numerous small finds.[18]

Geography

Alodia was located in Nubia, a region which, in the middle ages, extended from Aswan in southern Egypt to an undetermined point south of the confluence of the White and Blue Nile rivers.[19] The heartland of the kingdom was the Gezira, a fertile plain bounded by the White Nile in the west and the Blue Nile in the east.[20] In contrast to the White Nile Valley, the Blue Nile Valley is rich in known Alodian archaeological sites, among them Soba.[21] The extent of the Alodian influence to the south is unclear,[22] although it is likely that it bordered the Ethiopian highlands.[23] The southernmost known Alodian sites are in the proximity of Sennar.[lower-alpha 2]

To the west of the White Nile, Ibn Hawqal differentiated between Al-Jeblien, which was controlled by Makuria and probably corresponded with northern Kordofan, and the Alodian-controlled Al-Ahdin, which has been identified with the Nuba Mountains, and perhaps extended as far south as Jebel al Liri, near the modern border to South Sudan.[26] Nubian connections with Darfur have been suggested, but evidence is lacking.[27]

The northern region of Alodia probably extended from the confluence of the two Niles downstream to Abu Hamad near Mograt Island.[28] Abu Hamad likely constituted the northernmost outpost of the Alodian province known as al-Abwab ("the gates"),[29] although some scholars also suggest a more southerly location, nearer the Atbara River.[30] No evidence for a major Alodian settlement has been discovered north of the confluence of the two Niles,[31] although several forts have been recorded there.[32]

Lying between the Nile and the Atbara was the Butana,[33] grassland suitable for livestock.[28] Along the Atbara and the adjacent Gash Delta (near Kassala) many Christian sites have been noted.[34] According to Ibn Hawqal, a vassal king loyal to Alodia governed the region around the Gash Delta.[35] In fact, much of the Sudanese-Ethiopian-Eritrean borderlands, once under control of the Ethiopian Kingdom of Aksum, appear to have been under Alodian influence.[36] The accounts of both Ibn Hawqal and al-Aswani suggest that Alodia also controlled the desert along the Red Sea coast.[23]

History

Origins

The name Alodia might be of considerable antiquity, perhaps appearing first as Alut on a Kushite stela from the late 4th century BC. It appeared again as Alwa on a list of Kushite towns by the Roman author Pliny the Elder (1st century AD), said to be located south of Meroë.[37] Another town named Alwa is mentioned in a 4th-century Aksumite inscription, this time located near the confluence of the Nile and the Atbara rivers.[38]

By the early 4th century the Kingdom of Kush, which used to control much of Sudan's riverbanks, was in decline, and Nubians (speakers of Nubian languages) began to settle in the Nile Valley.[40] They originally lived west of the Nile, but changes in the climate forced them eastward, resulting in conflicts with Kush from at least the 1st-century BC.[41] In the mid-4th century the Nubians occupied most of the area once controlled by Kush,[38] while it was limited to the northern reaches of the Butana.[42] An Aksumite inscription mentions how the warlike Nubians also threatened the borders of the Aksumite kingdom north of the Tekeze River, resulting in an Aksumite expedition.[43] It describes a Nubian defeat by Aksumite forces and a subsequent march to the confluence of the Nile and Atbara. There the Aksumites plundered several Kushite towns, including Alwa.[38]

.jpg.webp)

Archaeological evidence suggests the Kingdom of Kush ceased to exist in the middle of the 4th century. It is not known whether the Aksumite expeditions played a direct role in its fall. It seems likely that the Aksumite presence in Nubia was short-lived.[44] Eventually, the region saw the development of regional centers whose ruling elites were buried in large tumuli.[45] Such tumuli, within what would become Alodia, are known from El-Hobagi, Jebel Qisi and perhaps Jebel Aulia.[46] The excavated tumuli of El-Hobagi are known to date to the late 4th century,[47] and contained an assortment of weaponry imitating Kushite royal funerary rituals.[48] Meanwhile, many Kushite temples and settlements, including the former capital Meroë, seem to have been largely abandoned.[49] The Kushites themselves were absorbed into the Nubians[50] and their language was replaced by Nubian.[51]

How the Kingdom of Alodia came into being is unknown.[52] Its formation was completed by the mid-6th century, when it is said to have existed alongside the other Nubian kingdoms of Nobadia and Makuria in the north.[30] Soba, which by the 6th century had developed into a major urban center,[53] served as its capital.[30] In 569 the Kingdom of Alodia was mentioned for the first time, being described by John of Ephesus as a kingdom on the cusp of Christianization.[52] Independently of John of Ephesus, the kingdom's existence is also verified by a late 6th century Greek document from Byzantine Egypt, describing the sale of an Alodian slave girl.[54]

Christianization and peak

.jpg.webp)

John of Ephesus' account describes the events around the Christianization of Alodia in detail. As the southernmost of the three Nubian kingdoms, Alodia was the last to be converted to Christianity. According to John, the Alodian King was aware of the conversion of Nobadia in 543 and asked him to send a bishop who would also baptize his people. The request was granted in 580 and Longinus was sent, leading to the baptism of the King, his family and the local nobility. Thus, Alodia became a part of the Christian world under the Coptic Patriarchate of Alexandria. After conversion, several pagan temples, such as the one in Musawwarat es-Sufra, were probably converted into churches.[56] The extent and speed with which Christianity spread among the Alodian populace is uncertain. Despite the conversion of the nobility, it is likely that Christianization of the rural population progressed only slowly, if at all.[57] John of Ephesus' report also implies tensions between Alodia and Makuria. Several forts north of the confluence of the two Niles have recently been dated to this period. However, their occupation did not exceed the 7th century, suggesting that the Makurian-Alodian conflict was soon resolved.[58]

Between 639 and 641, Muslim Arabs conquered Egypt from the Byzantine Empire.[59] Makuria, which by this time had been unified with Nobadia,[60] fended off two subsequent Muslim invasions, one in 641/642 and another in 652. In the aftermath, Makuria and the Arabs agreed to sign the Baqt, a peace treaty that included a yearly exchange of gifts and socioeconomic regulations between Arabs and Nubians.[61] Alodia was explicitly mentioned in the treaty as not being affected by it.[62] While the Arabs failed to conquer Nubia, they began to settle along the western coast of the Red Sea. They founded the port towns of Aydhab and Badi in the 7th century and Suakin, first mentioned in the 10th century.[63] From the 9th century, they pushed further inland, settling among the Beja throughout the Eastern Desert. Arab influence would remain confined to the east of the Nile until the 14th century.[64]

.jpg.webp)

Based on the archaeological evidence it has been suggested that Alodia's capital Soba underwent its peak development between the 9th and 12th centuries.[65] In the 9th century, Alodia was, albeit briefly, described for the first time by the Arab historian al-Yaqubi. In his short account, Alodia is said to be the stronger of the two Nubian kingdoms, being a country requiring a three-month journey to cross. He also recorded that Muslims would occasionally travel there.[66]

A century later, in the mid-10th century, Alodia was visited by traveler and historian Ibn Hawqal, resulting in the most comprehensive known account of the kingdom. He described the geography and people of Alodia in considerable detail, giving the impression of a large, polyethnic state. He also noted its prosperity, having an "uninterrupted chain of villages and a continuous strip of cultivated lands".[67] When Ibn Hawqal arrived, the ruling king was named Eusebius, who was, upon his death, succeeded by his nephew Stephanos.[68][69] Another Alodian king from this period was David, who is known from a tombstone in Soba. His rule was initially dated to 999–1015, but based on paleographical grounds it is now dated more broadly, to the 9th or 10th centuries.[70]

Ibn Hawqal's report describing Alodia's geography was largely confirmed by al-Aswani, a Fatimid ambassador sent to Makuria, who went on to travel to Alodia. In a similar manner to al-Yaqubi's description of 100 years before, Alodia was noted as being more powerful than Makuria, more extensive and having a larger army. The capital Soba was a prosperous town with "fine buildings, and extensive dwellings and churches full of gold and gardens", while also having a large Muslim quarter.[4]

Abu al-Makarim (12th century)[7] was the last historian to refer to Alodia in detail. It was still described as a large, Christian kingdom housing around 400 churches. A particularly large and finely constructed one was said to be located in Soba, called the "Church of Manbali".[71] Two Alodian kings, Basil and Paul, are mentioned in 12th century Arabic letters from Qasr Ibrim.[69]

There is evidence that at certain periods there were close relations between the Alodian and the Makurian royal families. It is possible that the throne frequently passed to a king whose father was of the royal family of the other state.[72] Nubiologist Włodzimierz Godlewski states that it was under the Makurian king Merkurios (early 8th century) that the two kingdoms began to approach each other.[73] In 943 al Masudi wrote that the Makurian king ruled over Alodia, while Ibn Hawqal wrote that it was the other way around.[72] The 11th century saw the appearance of a new royal crown in Makurian art; it has been suggested that this derived from the Alodian court.[74] King Mouses Georgios, who is known to have ruled in Makuria in the second half of the 12th century, most likely ruled both kingdoms via a personal union. Considering that in his royal title ("king of the Arouades and Makuritai") Alodia is mentioned before Makuria, he might have initially been an Alodian king.[75]

Decline

Archaeological evidence from Soba suggests a decline of the town, and therefore possibly the Alodian kingdom, from the 12th century.[76] By c. 1300 the decline of Alodia was well advanced.[77] No pottery or glassware postdating the 13th century has been identified at Soba.[78] Two churches were apparently destroyed during the 13th century, although they were rebuilt shortly afterwards.[79] It has been suggested that Alodia was under attack by an African, possibly Nilotic,[80] people called Damadim who originated from the border region of modern Sudan and South Sudan, along the Bahr el Ghazal River.[81] According to geographer Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi, they attacked Nubia in 1220.[82] Soba may have been conquered at this time, suffering occupation and destruction.[81] In the late 13th century, another invasion by an unspecified people from the south occurred.[83] In the same period poet al-Harrani wrote that Alodia's capital was now called Waylula,[77] described as "very large" and "built on the west bank of the Nile".[84] In the early 14th century geographer Shamsaddin al-Dimashqi wrote that the capital was a place named Kusha, located far from the Nile, where water had to be obtained from wells.[85] The contemporary Italian-Mallorcan Dulcert map features both Alodia ("Coale") and Soba ("Sobaa").[86]

Economic factors also seem to have played a part in Alodia's decline. From the 10th to 12th centuries the East African coast saw the rise of new trading cities such as Kilwa. These were direct mercantile competitors since they exported similar goods to Nubia.[87] A period of severe droughts occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa between 1150 and 1500 would have affected the Nubian economy as well.[88] Archeobotanical evidence from Soba suggests the town suffered from overgrazing and overcultivation.[89]

By 1276 al-Abwab, previously described as the northernmost Alodian province, was recorded as an independent splinter kingdom ruling over vast territories. The precise circumstances of its secession and its relations with Alodia thereafter remain unknown.[90] Based on pottery finds it has been suggested that al-Abwab continued to thrive until the 15th and perhaps even the 16th century.[91] In 1286 a Mamluke prince sent messengers to several rulers in central Sudan. It is not clear if they were still subject to the king in Soba[92] or if they were independent, implying a fragmentation of Alodia into multiple petty states by the late 13th century.[77] In 1317 a Mamluk expedition pursued Arab brigands as far south as Kassala in Taka (one of the regions which received a Mamluk messenger in 1286[92]), marching through al-Abwab and Makuria on their return.[93]

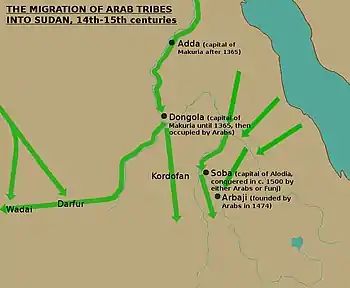

During the 14th and 15th centuries much of what is now Sudan was overrun by Arab tribes,[94] while the Adal Sultanate exerted some influence over the area around Suakin.[95][96] The bedouin may have profited from the plague which has been suggested to have ravaged Nubia in the mid-14th century killing many sedentary Nubians, but not affecting the nomadic Arabs.[97] They would have then intermixed with the remaining local population, gradually taking control over land and people,[98] greatly benefiting from their large population in spreading their culture.[99] The first recorded Arab migration to Nubia dates to 1324.[100] It was the disintegration of Makuria in the late 14th century that, according to archaeologist William Y. Adams, caused the "flood gates" to "burst wide open".[101] Many, initially coming from Egypt, followed the course of the Nile until they reached Al Dabbah. Here they headed west to migrate along the Wadi Al-Malik to reach Darfur or Kordofan.[102] Alodia, in particular the Butana and the Gezira, was the target of those Arabs who had lived among the Beja[103] in the Eastern Desert for centuries.[104]

Initially, the kingdom was able to exercise authority over some of the newly arrived Arab groups, forcing them to pay tribute. The situation grew increasingly precarious as more Arabs arrived.[105] By the second half of the 15th century, Arabs had settled in the entire central Sudanese Nile valley, except for the area around Soba,[98] which was all that was left of Alodia's domain.[106] In 1474[107] it was recorded that Arabs founded the town of Arbaji on the Blue Nile, which would quickly develop into an important centre of commerce and Islamic learning.[108] In around 1500 the Nubians were recorded to be in a state of total political fragmentation, as they had no king, but 150 independent lordships centered around castles on both sides of the Nile.[77] Archaeology attests that Soba was largely ruined by this time.[10]

Fall

It is unclear if the Kingdom of Alodia was destroyed by the Arabs under Abdallah Jammah or by the Funj, an African group from the south led by their king Amara Dunqas.[10] Most modern scholars agree now that it fell due to the Arabs.[109][110]

Abdallah Jammah ("Abdallah the gatherer"), the eponymous ancestor[111] of the Sudanese Abdallab tribe, was a Rufa'a[112] Arab who, according to Sudanese traditions, settled in the Nile Valley after coming from the east. He consolidated his power and established his capital at Qerri, just north of the confluence of the two Niles.[113] In the late 15th century he gathered the Arab tribes to act against the Alodian "tyranny", as it is called, which has been interpreted as having a religious-economic motive. The Muslim Arabs no longer accepted the rule of, nor taxation by, a Christian ruler. Under Abdallah's leadership Alodia and its capital Soba were destroyed,[114] resulting in rich booty such as a "bejeweled crown" and a "famous necklace of pearls and rubies".[113]

According to another tradition recorded in old documents from Shendi, Soba was destroyed by Abdallah Jammah in 1509 having already been attacked in 1474. The idea of uniting the Arabs against Alodia is said to have already been on the mind of an emir who lived between 1439 and 1459. To this end, he migrated from Bara in Kordofan to a mountain near Ed Dueim on the White Nile. Under his grandson, called Emir Humaydan, the White Nile was crossed. There he met other Arab tribes and attacked Alodia. The king of Alodia was killed, but the "patriarch", probably the archbishop of Soba, managed to flee. He soon returned to Soba. A puppet king was crowned and an army of Nubians, Beja and Abyssinians was assembled to fight "for the sake of religion". Meanwhile, the Arab alliance was about to fracture, but Abdallah Jammah reunited them, while also allying with the Funj king Amara Dunqas. Together they finally defeated and killed the patriarch, razing Soba afterwards and enslaving its population.[11]

The Funj Chronicle, a multi-authored[115] history of the Funj Sultanate compiled in the 19th century, ascribes the destruction of Alodia to King Amara Dunqas; he was also allied with Abdallah Jammah.[110] This attack is dated to the 9th century after the Hijra (c. 1396–1494). Afterwards, Soba is said to have served as the capital of the Funj until the foundation of Sennar in 1504.[116] The Tabaqat Dayfallah, a history of Sufism in Sudan (c. 1700), briefly mentions that the Funj attacked and defeated the "kingdom of the Nuba" in 1504–1505.[117]

Legacy

Historian Jay Spaulding proposes that the fall of Soba was not necessarily the end of Alodia. According to the Jewish traveler David Reubeni, who visited the country in 1523, there was still a "Kingdom of Soba" on the eastern bank of the Blue Nile, although he explicitly noted Soba itself was in ruins. This matches the oral traditions from the Upper Blue Nile, which claim that Alodia survived Soba's fall and still existed along the Blue Nile. It had gradually retreated to the mountains of Fazughli in the Ethiopian-Sudanese borderlands, forming the Kingdom of Fazughli.[118] Recent excavations in western Ethiopia seem to confirm the theory of an Alodian migration.[119] The Funj eventually conquered Fazughli in 1685 and its population, known as Hamaj, became a fundamental part of Sennar, eventually seizing power in 1761–1762.[120] As recently as 1930[111] Hamaj villagers in the southern Gezira would swear by "Soba the home of my grandfathers and grandmothers which can make the stone float and the cotton ball sink".[92]

In 1504–1505 the Funj founded the Funj sultanate, incorporating Abdallah Jammah's domain, which, according to some traditions, happened after a battle where Amara Dunqas defeated him.[121] The Funj maintained some medieval Nubian customs like the wearing of crowns with features resembling bovine horns, called taqiya umm qarnein,[122] the shaving of the head of a king upon his coronation,[123] and, according to Jay Spaulding, the custom of raising princes separately from their mothers, under strict confinement.[124]

The aftermath of Alodia's fall saw extensive Arabization, with the Nubians embracing the tribal system of the Arab migrants.[125] Those living along the Nile between al Dabbah in the north and the confluence of the two Niles in the south were subsumed into the Ja'alin tribe.[126] To the east, west and south of the Ja'alin the country was now dominated by tribes claiming a Juhaynah ancestry.[127] In the area around Soba, the tribal Abdallab identity prevailed.[128] The Nubian language was spoken in central Sudan until the 19th century, when it was replaced by Arabic.[129] Sudanese Arabic preserves many words of Nubian origin,[130] and Nubian place names can be found as far south as the Blue Nile state.[131]

The fate of Christianity in the region remains largely unknown.[132] The church institutions would have collapsed together with the fall of the kingdom,[125] resulting in the decline of the Christian faith and the rise of Islam in its stead.[133] Islamized groups from northern Nubia began to proselytize the Gezira.[134] As early as 1523 King Amara Dunqas, who was initially a Pagan or nominal Christian, was recorded to be Muslim.[135] Nevertheless, in the 16th century large portions of the Nubians still regarded themselves as Christians.[136] A traveler who visited Nubia around 1500 confirms this, while also saying that the Nubians were so lacking in Christian instruction they had no knowledge of the faith.[137] In 1520 Nubian ambassadors reached Ethiopia and petitioned the Emperor for priests. They claimed that no more priests could reach Nubia because of the wars between Muslims, leading to a decline of Christianity in their land.[138] In the first half of the 17th century, a prophecy made by the Sudanese Sheikh Idris Wad al-Arbab mentioned a church in the Nuba Mountains.[139] As late as the early 1770s there was said to be a Christian princedom in the Ethiopian-Sudanese border area, called Shaira.[140] Apotropaic rituals stemming from Christian practices outlived the conversion to Islam.[141] As late as the 20th century several practices of undoubtedly Christian origin were "common, though of course not universal, in Omdurman, the Gezira and Kordofan",[142] usually revolving around the application of crosses on humans and objects.[lower-alpha 3]

Soba, which remained inhabited until at least the early 17th century,[148] served, among many other ruined Alodian sites, as a steady supply of bricks and stones for nearby Qubba shrines, dedicated to Sufi holy men.[149] During the early 19th century many of the remaining bricks in Soba were plundered for the construction of Khartoum, the new capital of Turkish Sudan.[150]

Administration

While information about Alodia's government is sparse,[151] it was likely similar to that of Makuria.[152] The head of state was the king who, according to al-Aswani, reigned as an absolute monarch.[151] He was recorded to be able to enslave any of his subjects at will, who would not oppose his decision, but prostrated themselves before him.[153] As in Makuria, succession to the Alodian throne was matrilineal: it was the son of the king's sister, not his son who succeeded to the throne.[152] There might be evidence a mobile royal encampment existed, although the translation of the original source, Abu al-Makarim, is not certain.[154] Similar mobile courts are known to have existed in the early Funj sultanate, Ethiopia and Darfur.[155]

The kingdom was divided into several provinces under the sovereignty of Soba.[156] It seems delegates of the king governed these provinces.[151] Al-Aswani stated that the governor of the northern al-Abwab province was appointed by the king.[157] This was similar to what Ibn Hawqal recorded for the Gash Delta region, which was ruled by an appointed Arabophone (Arabic speaker).[35] In 1286, Mamluk emissaries were sent to several rulers in central Sudan. It is unclear whether those rulers were actually independent,[77] or if they remained subordinate to the king of Alodia. If the latter was the case, this would provide an understanding of the kingdom's territorial organization. The "Sahib" of al-Abwab[92] seems certain to have been independent.[90] Apart from al-Abwab, the following regions are mentioned: Al-Anag (possibly Fazughli); Ari; Barah; Befal; Danfou; Kedru (possibly after Kadero, a village north of Khartoum); Kersa (the Gezira); and Taka (the region around the Gash Delta).[158]

State and church were intertwined in Alodia,[159] with the Alodian kings probably serving as its patrons.[160] Coptic documents observed by Johann Michael Vansleb during the later 17th century list the following bishoprics in the Alodian kingdom: Arodias, Borra, Gagara, Martin, Banazi, and Menkesa.[161] "Arodias" may refer to the bishopric in Soba.[159] The bishops were dependent on the patriarch of Alexandria.[4]

Alodia may have had a standing army,[158] in which cavalry likely projected force and symbolized royal authority deep into the provinces.[162] Because of their speed, horses were also important for communication, providing a rapid courier service between the capital and the provinces.[162] Aside from horses, boats also played a central role in transportation infrastructure.[163]

| Name | Date of rule | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Giorgios | ? | Recorded on an inscription at Soba.[69] |

| David | 9th or 10th century | Recorded on his tombstone at Soba. Initially thought to have ruled from 999 to 1015, but now proposed to have lived in the 9th / 10th centuries.[70] |

| Eusebios | c. 938–955 | Mentioned by Ibn Hawqal.[69][164] |

| Stephanos | c. 955 | Mentioned by Ibn Hawqal.[69][164] |

| Mouses Georgios | c. 1155–1190 | Joint ruler of Makuria and Alodia. Recorded on letters from Qasr Ibrim and a graffito from Faras.[75] |

| ?Basil | 12th century | Recorded on an Arabic letter from Qasr Ibrim[69] and a graffito from Meroë(?).[165] |

| ?Paul | 12th century | Recorded on an Arabic letter from Qasr Ibrim.[69] |

Culture

Languages

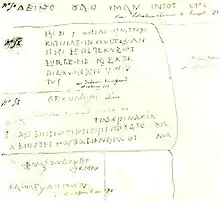

While Alodia was polyethnic, and hence polylingual,[166] it was essentially a Nubian state whose majority spoke a Nubian language.[167] Based on a few inscriptions found in Alodian territory it has been suggested that the Alodians spoke a dialect distinct from Old Nobiin of northern Nubia, dubbed as Alwan-Nubian. This assumption rests primarily on the script used in these inscriptions,[168] which, while also being based on the Greek alphabet,[169] differs from that employed in Makuria by making no use of Coptic diacritics and instead having special characters based on Meroitic hieroglyphs. However, ultimately the classification of this language and its relationship to Old Nobiin has yet to be specified.[170] In the 1830s it was said a Nubian language was still being spoken as far south as Berber near the junction of the Nile and the Atbara. It was supposedly similar to Kenzi but with many differences.[171]

Although Greek, a prestigious sacral language, was used, it does not appear to have been spoken.[172] An example of the use of Greek in Alodia is the tombstone of King David from Soba, where it is written with quite correct grammar.[173] Al-Aswani noted that books were written in Greek and then translated into Nubian.[4] The Christian liturgy was also in Greek.[174] Coptic was probably used to communicate with the Patriarch of Alexandria,[152] but written Coptic remains are very sparse.[175]

Apart from Nubian, a multitude of languages were spoken throughout the kingdom. In the Nuba mountains several Kordofanian languages occurred together with Hill Nubian dialects. Upstream along the Blue Nile Eastern Sudanic languages like Berta or Gumuz were spoken. In the eastern territories lived the Beja, who spoke their own Cushitic language, as did the Semitic Arabs[1] and the Tigre.[2]

Church architecture

The existence of 400 churches has been recorded throughout the kingdom; most have yet to be located.[176] Only seven have been identified so far, given the simple names of church "A", "B", "C", "E", the "Mound C" church in Soba, the church in Saqadi and the temple-church in Musawwarat as-Sufra.[177] A hypothetical church was recently discovered in Abu Erteila in the western Butana.[178] Churches "A"–"C" as well as the "Mound C" church were basilicas comparable to the largest Makurian churches. The Saqadi church was an insertion into a pre-existing structure. Church "E" and the church of Musawwarat es-Sufra were "normal" churches. Thus, the known Alodian houses of worship can be categorized into three classes.[176]

.jpg.webp)

On "Mound B" in Soba lay the standalone complex of the three churches "A", "B" and "C". Churches "A" and "B", both probably built in the mid-9th century, were large buildings, the first measuring 28 m × 24.5 m (92 ft × 80 ft) and the second 27 m × 22.5 m (89 ft × 74 ft). Church "C" was much smaller [179] and built after the other two churches, probably after c. 900.[78] The three churches had many similarities, including having a narthex, wide entrances on the main east-west axis and a pulpit along the north side of the nave. Differences are evident in the thickness of the bricks used. Church "C" lacked outer aisles.[180] It seems probable that the complex was the ecclesiastical center of Soba, if not the entire kingdom.[181]

Church "E", on a natural mount, was 16.4 m × 10.6 m (54 ft × 35 ft) in size (and like all red brick structures in Soba heavily robbed).[182] Its layout was unusual,[183] such as its L-shaped narthex.[184] The roof was supported by wooden beams resting on stone pedestals. The internal walls used to be covered by painted whitewashed mud; the external walls were rendered in white lime mortar.[185]

The "Mound C" church, perhaps the oldest of the churches of Soba,[186] was around 13.5 m (44 ft) in length. It was the only Alodian church known to have incorporated stone columns.[176] Very little remains of it and its walls, probably made of red bricks, have completely disappeared. Five capitals have been noted, belonging to a style that appeared in Nubia at the turn of the 8th century.[187]

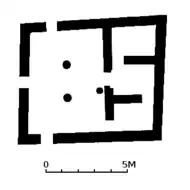

The church of Musawwarat es-Sufra, called "Temple III A", was initially a pagan temple but was converted into a church, probably soon after the royal conversion in 580.[188] It was rectangular and slightly skewed, being 8.6 m–8.8 m × 7.4 m–7.6 m (28 ft–29 ft × 24 ft–25 ft) in size. It was divided into one large and three small rooms.[183] The roof, of an indeterminate shape, was supported by wooden beams.[189] Despite originally being a Kushite temple it still bears similarities to purpose-built churches, for example having an entrance on both the north and south sides.[183]

The southernmost known Nubian church was in Saqadi,[24] a red brick building[190] inserted into a pre-existing building of unknown nature.[176] It had a nave, where two L-shaped walls projected, and at least two aisles with rectangular brick piers between, as well as a range of possibly three rooms across the western end, which was a typically Nubian arrangement.[190]

Nubian church architecture was greatly influenced by that of Egypt, Syria and Armenia.[191] The constellation of the "Mound B" complex might reflect Byzantine influences.[192] The relations between the church architecture of Makuria and Alodia remain uncertain.[193] What seems clear is that Alodian churches lacked eastern entrances and tribunes, features characteristic for churches in northern Nubia.[194] Furthermore, Alodian churches used more wood.[192] Similarities with medieval Ethiopian church architecture are harder to find, only a few details matching.[190]

Pottery

In medieval Nubia, pottery and its decoration were appreciated as an art form.[195] Until the 7th century, the most common pottery type found at Soba was the so-called "Red Ware". These wheel-made hemispherical bowls were made of red or orange slip and painted with separated motifs such as boxes with inner cross-hatchings, stylized floral motifs or crosses. The outlines of the motifs were drawn in black while the interiors were white. In their design, they are a direct continuation of Kushite styles, with possible influences from Aksumite Ethiopia. Due to their relative rarity, it has been suggested that they were imported, although they bear similarities to the pottery type, known as "Soba Ware", that succeeded them.[196]

"Soba Ware" was a type of wheel-made[197] pottery with a distinctive decoration very different from that found in the rest of Nubia.[198] The shape of the pottery was diverse, as was the repertoire of painted decoration. One of the most distinctive features was the use of faces as painted decoration. They were simplified, if not geometric, in form and with big round eyes. This style is foreign to Makuria and Egypt, but bears a resemblance to paintings and manuscripts from Ethiopia.[199] It is possible the potters copied these motifs from local church murals.[200] Also unique was the application of animal-shaped bosses (protomes).[201] Glazed vessels were also produced, copying Persian aquamaniles without reaching their quality.[202] Beginning in the 9th century, "Soba Ware" was increasingly replaced by fine ware imported from Makuria.[203]

Economy

Agriculture

Tardieu_Am%C3%A9d%C3%A9e_bpt6k6209333w_621.jpg.webp)

Alodia was in the savannah belt, giving it an economic advantage over its northern neighbor Makuria.[5] According to al-Aswani the "provisions of the country of Alwa and their king" came from Kersa, which has been identified with the Gezira.[156] North of the confluence of the two Niles agriculture was limited to farms along the river[28] watered by devices like the shadoof or the more sophisticated sakia.[205] In contrast, the farmers of the Gezira profited from sufficient rainfall to make rainfall cultivation the economic mainstay.[206] Archaeological records have provided insight into the types of food grown and consumed in Alodia. At Soba, the primary cereal was sorghum, although barley and millet were also known to be consumed.[207] Al-Aswani noted that sorghum was used to make beer and said that vineyards were quite rare in Alodia compared to Makuria.[208] There is archaeological evidence of grapes.[209] According to al-Idrisi, onions, horseradish, cucumbers, watermelons and rapeseed were also cultivated,[210] but none were found at Soba.[211] Instead, figs, acacia fruits, doum palm fruits and dates have been identified.[212]

Sedentary farmers formed one part of Alodia's agriculture, the other consisted of nomads practicing animal husbandry.[152] The relationship between these two groups was symbiotic, resulting in an exchange of goods.[213] Al-Aswani wrote that beef was plentiful in Alodia, which he attributed to the bountiful grazing land.[153] Archaeological evidence from Soba attests to the relevance cattle had there,[214] as most animal bones are attributed to that species, followed by those of sheep and goats.[215] Chickens were probably also bred at Soba,[214] although available archaeological proof is very limited, probably due to the fragile nature of bird bones.[216] No remains of pigs have been identified.[215] Camel remains have been noted, but none bore signs of butchery.[217] Fishing and hunting made only minor contributions to the overall diet of Soba.[213]

Trade

Trade was an important source of income for the people of Alodia. Soba served as a trading hub with north-south and east-west trade routes; goods arrived in the kingdom from Makuria, the Middle East, western Africa, India and China.[218] Trade with Makuria probably ran through the Bayuda Desert, following Wadi Abu Dom or Wadi Muqaddam, while another route went from near Abu Hamad to Korosko in Lower Nubia. A route going east originated around Berber near the confluence of the Nile and the Atbara, terminating in Badi, Suakin and Dahlak.[219] Merchant Benjamin of Tudela mentions a route heading west, going from Alodia to Zuwila in Fezzan.[220] Archaeological evidence for trade with Ethiopia is virtually absent,[221] although trading relations are suggested by other evidence.[lower-alpha 4] Trading with the outside world was handled predominantly by Arab merchants.[226] Muslim merchants were recorded as having traversed Nubia, some living in a district in Soba.[227]

Exports from Alodia likely included raw materials such as gold, ivory, salt and other tropical products,[228] as well as hides.[229] According to an oral tradition Arab merchants came to Alodia to sell silk and textiles, receiving beads, elephant teeth and leather in return.[230] At Soba silk and flax have been found, both probably originating from Egypt.[231] Most of the glass found there was also imported.[79] Benjamin of Tudela claimed merchants traveling from Alodia to Zuwila carried hides, wheat, fruits, legumes and salt, while carrying gold and precious stones on their return.[232] Slaves are commonly assumed to have been exported by medieval Nubia.[233] Adams postulates that Alodia was a specialized slave-trading state that exploited the pagan populations to the west and south.[234] Evidence for a regulated slave trade is very limited.[235][lower-alpha 5] It is only from the 16th century, after the fall of the Christian kingdoms, that such evidence begins to appear.[237]

Notes

- Kordofanian languages; various Eastern Sudanic languages spoken in the Upper Blue Nile Valley (for example Berta); Arabic, Beja;[1] and Tigre[2]

- "The most southerly church known, which presumably was within the kingdom of Alwa, lay at Saqadi 50 km to the west of Sennar",[24] while "the most southerly find of Alwan material on the Blue Nile is a pottery chalice, from Khalil el-Kubra 40 km upstream of Sennar".[25]

- In 1918 it was recorded that in parts of Omdurman, the Gezira and Kordofan, practices of Christian origin included the marking of crosses on foreheads of newborns or on stomachs of sick boys as well as putting straw crosses on bowls of milk.[143] In 1927 it was recorded that along the White Nile, crosses were painted on bowls filled with wheat.[144] In 1930 it was not only recorded that youths in Fazughli and the Gezira would be painted with crosses, but also that coins with crosses were worn to provide assistance against illnesses.[145] A very similar custom was known from Lower Nubia, where women wore such coins on special holidays. It seems likely that this was a living memory of the Jizya tax, which was enforced on Christians who refused to convert to Islam.[146] Christianizing rituals are also known from the Nuba mountains: crosses were painted on foreheads and breasts and were applied to blankets and baskets.[147]

- John of Ephesus wrote of Aksumites in Alodia, possibly referring to merchants,[222] while the contemporary Cosmas Indicopleustes reported Aksumite trade expeditions into the Blue Nile Valley, so arguably in the Alodian sphere of influence. In the 12th century al-Idrisi made mention of a trading town in the northern Butana, a place "where merchants from Nubia and Ethiopia gather together with those from Egypt".[223] Historian Mordechai Abir suggests that merchants from the Zagwe kingdom traveled through Alodia to reach Egypt.[224] Some Ethiopian traditions recall a people named "Soba Noba".[225]

- The African slave armies that were deployed in Egypt by the Tulunids, Ikhshidids and Fatimids are often cited as evidence for a Nubian slave trade, but it is more likely these slaves came from the Chad basin instead. (In Fatimid sources they appear as Zuwayla, indicating an origin from Zuwila in Fezzan.)[236]

References

Citations

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 89–90.

- Zaborski 2003, p. 471.

- Lajtar 2009, pp. 93–94.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 20.

- Welsby 2014, p. 183.

- Welsby 2014, p. 197.

- Werner 2013, p. 93.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 15–23.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 12–15.

- Welsby 2002, p. 255.

- Vantini 2006, pp. 487–491.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 19–20.

- Welsby 2002, p. 9.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 58–70.

- Werner 2013, p. 25.

- Edwards 2004, p. 221.

- Drzewiecki et al. 2018, p. 28.

- Werner 2013, pp. 161–164.

- Werner 2013, pp. 28–29.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 41.

- Welsby 2014, Figure 2.

- Obluski 2017, p. 15.

- Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 8.

- Welsby 2002, p. 86.

- Welsby 2014, p. 185.

- Spaulding 1998, p. 49.

- Edwards 2004, p. 253.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 74.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 21–22.

- Welsby 2002, p. 26.

- Welsby 2014, p. 192.

- Welsby 2014, pp. 188–190.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 62.

- Welsby 2014, p. 187.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 98.

- Fattovich 1984, pp. 105–106.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 8.

- Hatke 2013, §4.5.2.3.

- Rilly 2008, Fig. 3.

- Rilly 2008, p. 211.

- Rilly 2008, pp. 216–217.

- Werner 2013, p. 35.

- Hatke 2013, §4.5.2.1., see also §4.5. for the discussion of a Greek inscription with similar content.

- Hatke 2013, §4.6.3.

- Welsby 2002, pp. 22–23.

- Welsby 2014, p. 191.

- Welsby 2002, p. 28.

- Welsby 2002, pp. 40–41.

- Edwards 2004, p. 187.

- Werner 2013, p. 39.

- Edwards 2004, p. 182.

- Werner 2013, p. 45.

- Welsby 1998, p. 20.

- Pierce 1995, pp. 148–166.

- Tsakos & Kleinitz 2018, p. 127.

- Werner 2013, pp. 51–62.

- Edwards 2001, p. 95.

- Drzewiecki & Cedro 2019, p. 129.

- Welsby 2002, p. 68.

- Werner 2013, p. 77.

- Welsby 2002, pp. 68–71.

- Welsby 2002, p. 77.

- Power 2008.

- Adams 1977, pp. 553–554.

- Shinnie 1961, p. 76.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 16–17.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 17–19.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 17.

- Welsby 2002, p. 261.

- Lajtar 2003, p. 203.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 22–23.

- Welsby 2002, p. 89.

- Godlewski 2012, p. 204.

- Danys & Zielinska 2017, p. 184.

- Lajtar 2009, pp. 89–94.

- Welsby 2002, p. 252.

- O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 19.

- Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 34.

- Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 9.

- Beswick 2004, p. 24.

- Werner 2013, p. 115.

- Vantini 1975, p. 400.

- Hasan 1967, p. 130.

- Vantini 1975, p. 448.

- Adams 1977, pp. 537–538.

- Hirsch 1990, p. 88.

- Grajetzki 2009, pp. 121–122.

- Zurawski 2014, p. 84.

- Cartwright 1999, p. 256.

- Welsby 2002, p. 254.

- Werner 2013, pp. 127, 159.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 99.

- Werner 2013, p. 138.

- Hasan 1967, p. 176.

- Owens, Travis. Beleaguered Muslim Fortresses and Ethiopian Imperial Expansion From the 13th to the 16th Century (PDF). Naval Postgraduate School. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2020.

- Pouwels, Randall (31 March 2000). The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-8214-4461-0.

- Werner 2013, pp. 142–143.

- Hasan 1967, p. 128.

- Hasan 1967, p. 175.

- Hasan 1967, p. 106.

- Adams 1977, p. 556.

- Braukämper 1992, pp. 108–109, 111.

- Hasan 1967, p. 145.

- Adams 1977, p. 554.

- Hasan 1967, pp. 129, 132–133.

- Adams 1977, p. 545.

- Vantini 1975, p. 784.

- McHugh 1994, p. 38.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 25.

- Adams 1977, p. 538.

- Adams 1977, p. 539.

- Hasan 1967, p. 132.

- O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 23.

- Hasan 1967, pp. 132–133.

- Hasan 1967, p. 213.

- Vantini 1975, pp. 786–787.

- Vantini 1975, pp. 784–785.

- Spaulding 1974, pp. 12–21.

- Gonzalez-Ruibal & Falquina 2017, pp. 16–18.

- Spaulding 1974, pp. 21–25.

- O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 25–26.

- Zurawski 2014, pp. 148–149.

- Zurawski 2014, p. 149.

- Spaulding 1985, p. 23.

- Werner 2013, p. 156.

- Adams 1977, pp. 557–558.

- Adams 1977, p. 558.

- O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 29.

- Edwards 2004, p. 260.

- Abu-Manga 2009, p. 377.

- Taha 2012, p. 10 (Taha ascribes these names a Dongolawi Nubian origin).

- Werner 2013, p. 171.

- Adams 1977, p. 564.

- McHugh 1994, p. 59.

- Werner 2013, pp. 170–171.

- Zurawski 2014, pp. 84–85.

- Hasan 1967, pp. 131–132.

- Werner 2013, p. 150.

- Werner 2013, p. 181.

- Spaulding 1974, p. 22, note 31.

- Werner 2013, p. 177.

- Crowfoot 1918, p. 56.

- Crowfoot 1918, pp. 55–56.

- Werner 2013, pp. 177–178.

- Chataway 1930, p. 256.

- Werner 2013, p. 178.

- Werner 2013, p. 182.

- Crawford 1951, pp. 28–29.

- McHugh 2016, p. 110.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 43.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 97.

- Obluski 2017, p. 16.

- Vantini 1975, p. 614.

- Seignobos 2015, p. 224.

- Spaulding 1972, p. 52.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 100.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 19.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 98–100.

- Werner 2013, p. 165.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 101.

- Crawford 1951, p. 26.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 22.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 85.

- Vantini 1975, p. 153.

- Munro-Hay 1982, p. 113.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 88–90.

- Werner 2013, p. 46.

- Breyer 2014, pp. 188–189.

- Werner 2013, p. 186, note 6.

- Breyer 2014, pp. 189–190.

- Russegger 1843, p. 456.

- Ochala 2014, pp. 43–44.

- Welsby & Daniels 1991, pp. 274–276.

- Werner 2013, p. 197.

- Ochala 2014, p. 37.

- Welsby 2002, p. 153.

- Welsby 2002, p. 149, note 38.

- Baldi & Varriale 2010, pp. 284–288.

- Werner 2013, p. 163.

- Welsby 1996, p. 188.

- Edwards 2004, p. 222.

- Welsby 1998, pp. 28–29.

- Welsby 2002, p. 154.

- Welsby 1998, p. 275.

- Welsby 1998, pp. 30–32.

- Welsby 1996, p. 187.

- Welsby & Daniels 1991, pp. 321–322.

- Török 1974, p. 100.

- Török 1974, p. 95.

- Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 322.

- Welsby 2002, p. 155.

- Werner 2013, p. 164.

- Welsby 2002, p. 149.

- Welsby 1996, p. 189.

- Welsby 2002, p. 194.

- Danys & Zielinska 2017, pp. 177–178.

- Danys & Zielinska 2017, p. 182.

- Welsby 2002, p. 234.

- Danys & Zielinska 2017, pp. 179–181.

- Welsby 2002, p. 235.

- Danys & Zielinska 2017, p. 180.

- Welsby 2002, pp. 194–195.

- Danys & Zielinska 2017, p. 183.

- Welsby 2002, p. 185.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 77–79.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 75.

- Welsby & Daniels 1991, pp. 265–267.

- Vantini 1975, p. 613.

- Welsby 2002, p. 186.

- Vantini 1975, p. 274.

- Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 273.

- Welsby & Daniels 1991, Table 16.

- Welsby 2002, p. 188.

- Welsby 1998, p. 245.

- Welsby 2002, p. 187.

- Welsby 1998, p. 241.

- Welsby 1998, p. 240.

- Werner 2013, p. 166.

- Welsby 2002, p. 213.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 87.

- Welsby 2002, pp. 214–215.

- Hatke 2013, §5.3.

- Welsby 2002, p. 215.

- Abir 1980, p. 15.

- Brita 2014, p. 517.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 86.

- Hasan 1967, p. 46.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 84.

- Zarroug 1991, p. 82.

- Abd ar-Rahman 2011, p. 52.

- Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 307.

- Hess 1965, p. 17.

- Edwards 2011, pp. 87–88.

- Adams 1977, p. 471.

- Edwards 2011, p. 103.

- Edwards 2011, pp. 89–90.

- Edwards 2011, pp. 95–96.

Sources

- Abd ar-Rahman, Rabab (2011). "آثار مملكة علوة 500م – 1500م (إقليم سوبا) رباب عبد الرحمن" [The archaeology of the Alwa kingdom 500 AD – 1500 AD (Soba region)] (PDF) (in Arabic). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-19. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- Abir, Mordechai (1980). Ethiopia and the Red Sea: The Rise and Decline of the Solomonic Dynasty and Muslim European Rivalry in the Region. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-3164-6.

- Abu-Manga, Al-Amin (2009). "Sudan". In Kees Versteegh (ed.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Languages and Linguistics. Volume IV. Q–Z. Brill. pp. 367–375. ISBN 978-90-04-17702-4.

- Adams, William Y. (1977). Nubia. Corridor to Africa. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09370-3.

- Baldi, Marco; Varriale, Maria Rita (2010). "An Hypothetical 3D Reconstruction of the So-Called Church in Abu Ertelia". Africa. Istituto italo-africano. 1–4. ISSN 0001-9747.

- Beswick, Stephanie (2004). Sudan's Blood Memory. University of Rochester. ISBN 978-1-58046-231-0.

- Braukämper, Ulrich (1992). Migration und ethnischer Wandel. Untersuchungen aus der östlichen Sahelzone ["Migration and ethnic change. Investigations from the eastern Sahel zone"] (in German). Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-05830-8.

- Breyer, Francis (2014). Einführung in die Meroitistik (in German). Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-12805-8.

- Brita, Antonella (2014). "Soba Noba". In Siegbert Uhlig, Alessandro Bausi (ed.). Encyclopedia Aethiopica. Vol. 5. Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 517. ISBN 978-3-447-06740-9.

- Cartwright, Caroline R. (1999). "Reconstructing the Woody Resources of the Medieval Kingdom of Alwa, Sudan". In Marijke van der Veen (ed.). The Exploitation of Plant Resources in Ancient Africa. Kluwer Academic/Plenum. pp. 241–259. ISBN 978-1-4757-6730-8.

- Chataway, J.D.P. (1930). "Notes on the history of the Fung" (PDF). Sudan Notes and Records. 13: 247–258.

- Crawford, O.G.S. (1951). The Fung Kingdom of Sennar. John Bellows Ltd. OCLC 253111091.

- Crowfoot, J.W. (1918). "The sign of the cross" (PDF). Sudan Notes and Records. 1: 55–56, 216.

- Danys, Katarzyna; Zielinska, Dobrochna (2017). "Alwan art. Towards an insight into the aesthetics of the Kingdom of Alwa through the painted pottery decoration". Sudan&Nubia. 21: 177–185. ISSN 1369-5770.

- Drzewiecki, Mariusz; Cedro, Aneta; Ryndziewicz, Robert; Khogli Ali Ahmed, Selma (2018). Expedition to Hosh el-Kab, Abu Nafisa, and Umm Marrahi forts. Preliminary report from the second season of fieldwork conducted from November 13th to December 8th, 2018 with an appendix on an aerial survey of Soba East on 12th and 13th December 2018 (Report). Omdurman. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.26111.66724/1.

- Drzewiecki, Mariusz; Cedro, Aneta (2019). "Recent Research at Jebel Umm Marrahi (Khartoum Province)". Der antike Sudan. Mitteilungen der sudanarchäologische Gesellschaft zu Berlin e.V. Sudanarchäologische Gesellschaft zu Berlin: 117–130. ISSN 0945-9502.

- Edwards, David (2001). "The Christianisation of Nubia: Some archaeological pointers". Sudan & Nubia. 5: 89–96. ISSN 1369-5770.

- Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past: An Archaeology of the Sudan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-36987-9.

- Edwards, David (2011). "Slavery and Slaving in the Medieval and Post-Medieval kingdoms of the Middle Nile". In Paul Lane and Kevin C. MacDonald (ed.). Comparative Dimensions of Slavery in Africa: Archaeology and Memory. British Academy. pp. 79–108. ISBN 978-0-19-726478-2.

- Fattovich, Rodolfo (1984). "Remarks on the peopling of the northern Ethiopian Sudanese borderland in ancient historical times". Rivista degli studi orientali. Fabrizio Serra Editore. 58: 85–106. ISSN 0392-4866.

- Gonzalez-Ruibal, Alfredo; Falquina, Alvaro (2017). "In Sudan's Eastern Borderland: Frontier Societies of the Qwara Region (ca. AD 600–1850)". Journal of African Archaeology. 15 (2): 173–201. doi:10.1163/21915784-12340011. ISSN 1612-1651.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2009). "Das Ende der christlich-nubischen Reiche ["The end of the Christian Nubian realms"]" (PDF). Internet-Beiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie (in German). Golden House Publications. X. ISBN 978-1-906137-13-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-02. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- Godlewski, Wlodzimierz (2012). "Merkurious". In Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong; Steven J. Niven (eds.). Dictionary of African Biography. Vol. 4. Oxford University. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- Hasan, Yusuf Fadl (1967). The Arabs and the Sudan. From the seventh to the early sixteenth century. Edinburgh University Press. OCLC 33206034.

- Hatke, G. (2013). Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa. NYU. ISBN 978-0-8147-6066-6.

- Hess, Robert L. (1965). "The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela: A Twelfth-Century Jewish Description of North-East Africa". The Journal of African History. 6 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1017/S0021853700005302. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 161989448.

- Hirsch, Betrand (1990). "L'espace nubien et éthiopien sur les cartes portulans du XIVe siècle". Médiévales (in French). Centre de recherche de l'Université de Paris. 9 (18): 69–92. doi:10.3406/medi.1990.1168. ISSN 0751-2708.

- Lajtar, Adam (2003). Catalogue of the Greek Inscriptions in the Sudan National Museum at Khartoum. Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-1252-6.

- Lajtar, Adam (2009). "Varia Nubica XII-XIX" (PDF). The Journal of Juristic Papyrology (in German). XXXIX: 83–119. ISSN 0075-4277.

- McHugh, Neil (1994). Holymen of the Blue Nile: The Making of an Arab-Islamic Community in the Nilotic Sudan. Northwestern University. ISBN 978-0-8101-1069-4.

- McHugh, Neil (2016). "Historical perspectives on the domed shrine in the Nilotic Sudan". In Abdelmajid Hannoum (ed.). Practicing Sufism: Sufi Politics and Performance in Africa. Routledge. pp. 105–130. ISBN 978-1-138-64918-7.

- Munro-Hay, S. C. (1982). "Kings and Kingdoms of Ancient Nubia". Rassegna di Studi Etiopici. Istituto per l'Oriente C. A. Nallino. 29: 87–137. ISSN 0390-0096.

- Obluski, Artur (2017). "Alwa". In Saheed Aderinto (ed.). African Kingdoms: An Encyclopedia of Empires and Civilizations. ABC-CLIO. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-1-61069-580-0.

- Ochala, Grzegorz (2014). "Multilingualism in Christian Nubia: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches". Dotawo. A Journal of Nubian Studies. Journal of Juristic Papyrology. 1. doi:10.5070/D61110007. ISBN 978-0-692-22914-9. S2CID 128122460.

- O'Fahey, R.S.; Spaulding, Jay L. (1974). Kingdoms of the Sudan. Methuen Young Books. ISBN 978-0-416-77450-4.

- Pierce, Richard Holton (1995). "A sale of an Alodian slave girl: A reexamination of papyrus Strassburg Inv. 1404". Symbolae Osloenses. LXX: 148–166. doi:10.1080/00397679508590895. ISSN 0039-7679.

- Power, Tim (2008). "The Origin and Development of the Sudanese Ports ('Aydhâb, Bâ/di', Sawâkin) in the early Islamic Period". Chroniques Yéménites. 15: 92–110. ISSN 1248-0568.

- Rilly, Claude (2008). "Enemy brothers: Kinship and relationship between Meroites and Nubians (Noba)". Between the Cataracts: Proceedings of the 11th Conference of Nubian Studies, Warsaw, 27 August – 2 September 2006. Part One. PAM. pp. 211–225. ISBN 978-83-235-0271-5.

- Russegger, Joseph (1843). Reise in Egypten, Nubien und Ost-Sudan (in German). Schweizerbart'sche Verlagshandlung. OCLC 311212367.

- Seignobos, Robin (2015). "Les évêches Nubiens: Nouveaux témoinages. La source de la liste de Vansleb et deux autres textes méconnus". In Adam Lajtar; Grzegorz Ochala; Jacques van der Vliet (eds.). Nubian Voices II. New Texts and Studies on Christian Nubian Culture (in French). Raphael Taubenschlag Foundation. ISBN 978-83-938425-7-5.

- Shinnie, P. (1961). Excavations at Soba. Sudan Antiquities Service. OCLC 934919402.

- Spaulding, Jay (1972). "The Funj: A Reconsideration". The Journal of African History. 13 (1): 39–53. doi:10.1017/S0021853700000256. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 161129633.

- Spaulding, Jay (1974). "The Fate of Alodia" (PDF). Meroitic Newsletter. 15: 12–30. ISSN 1266-1635.

- Spaulding, Jay (1985). The Heroic Age in Sennar. Red Sea. ISBN 978-1-56902-260-3.

- Spaulding, Jay (1998). "Early Kordofan". In Endre Stiansen and Michael Kevane (ed.). Kordofan Invaded: Peripheral Incorporation in Islamic Africa. Brill. pp. 46–59. ISBN 978-90-04-11049-6.

- Taha, A. Taha (2012). "The influence of Dongolawi Nubian on Sudan Arabic" (PDF). California Linguistic Notes. XXXVII. ISSN 0741-1391.

- Török, Laszlo (1974). "Ein christianisiertes Tempelgebäude in Musawwarat es Sufra (Sudan) ["A Christianized temple building in Musawwarat es Sufra (Sudan)"]" (PDF). Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae (in German). 26: 71–104. ISSN 0001-5210.

- Tsakos, Alexandros; Kleinitz, Cornelia (2018). "Medieval graffiti in the sandstone quarries of Meroe: texts, monograms and cryptograms of Christian Nubia". The Quarries of Meroe, Sudan. Vol. Part 1, Text. HBKU. pp. 127–142. ISBN 978-9927-118-87-6.

- Vantini, Giovanni (1975). Oriental Sources concerning Nubia. Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 174917032.

- Vantini, Giovanni (2006). "Some new light on the end of Soba". In Alessandro Roccati and Isabella Caneva (ed.). Acta Nubica. Proceedings of the X International Conference of Nubian Studies Rome 9–14 September 2002. Libreria Dello Stato. pp. 487–491. ISBN 978-88-240-1314-7.

- Welsby, Derek (1996). "The Medieval Kingdom of Alwa". In Rolf Gundlach; Manfred Kropp; Annalis Leibundgut (eds.). Der Sudan in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart (Sudan Past and Present). Peter Lang. pp. 179–194. ISBN 978-3-631-48091-5.

- Welsby, Derek (1998). Soba II. Renewed excavations within the metropolis of the Kingdom of Alwa in Central Sudan. British Museum. ISBN 978-0-7141-1903-8.

- Welsby, Derek (2002). The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia. Pagans, Christians and Muslims Along the Middle Nile. British Museum. ISBN 978-0-7141-1947-2.

- Welsby, Derek (2014). "The Kingdom of Alwa". In Julie R. Anderson; Derek A. Welsby (eds.). The Fourth Cataract and Beyond: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference for Nubian Studies. Peeters Publishers. pp. 183–200. ISBN 978-90-429-3044-5.

- Welsby, Derek; Daniels, C.M. (1991). Soba. Archaeological Research at a Medieval Capital on the Blue Nile. The British Institute in Eastern Africa. ISBN 978-1-872566-02-3.

- Werner, Roland (2013). Das Christentum in Nubien. Geschichte und Gestalt einer afrikanischen Kirche ["Christianity in Nubia. History and shape of an African church"] (in German). Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-12196-7.

- Zaborski, Andrzej (2003). "Baqulin". In Siegbert Uhlig (ed.). Encyclopedia Aethiopica. Vol. 1. Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 471. ISBN 978-3-447-04746-3.

- Zarroug, Mohi El-Din Abdalla (1991). The Kingdom of Alwa. University of Calgary Press. ISBN 978-0-919813-94-6.

- Zurawski, Bogdan (2014). Kings and Pilgrims. St. Raphael Church II at Banganarti, mid-eleventh to mid-eighteenth century. IKSiO PAN. ISBN 978-83-7543-371-5.

Further reading

- Drzewiecki, Mariusz; Michalik, Tomasz (2021). "The beginnings of the Alwan capital of Soba in light of new archaeological evidence". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. University of Warsaw. 30/2 (30/2): 419–438. doi:10.31338/uw.2083-537X.pam30.2.09. ISSN 2083-537X. S2CID 247652880.

- Drzewiecki, Mariusz; Ryndziewicz, Robert (2019). "Developing a New Approach to Research at Soba, the Capital of the Medieval Kingdom of Alwa" (PDF). Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress. 15 (2): 314–337. doi:10.1007/s11759-019-09370-x. ISSN 1935-3987. S2CID 200040640.

- Gerhards, Gabriel (2021). "Some notes on the Christian medieval heritage of the Gezira (central Sudan)". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. University of Warsaw. 30/2 (30/2): 439–460. doi:10.31338/uw.2083-537X.pam30.2.12. ISSN 2083-537X. S2CID 247653902.