Amédée-François Frézier

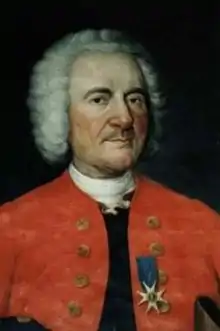

Amédée-François Frézier (French: [amede fʁɑ̃swa fʁezje]1682 – October 26, 1773) was a French military engineer, mathematician, spy, and explorer who is best remembered for bringing back five specimens of Fragaria chiloensis, the beach strawberry, from an assignment in South America, thus introducing this New World fruit to the Old. The standard author abbreviation Frez. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[1]

Amédée-François Frézier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1682 Chambéry, Savoy, France |

| Died | October 26, 1773 Brest, Brittany, France |

| Occupation(s) | Engineer, mathematician, spy, explorer |

| Parent | Pierre-Louis Frézier |

Family history

As described by G.M. Darrow, Frézier's ancient surname was derived from fraise, the French word for strawberry.[2] A story relates the surname is derived from the fact that Julius de Berry, a citizen of Anvers (i.e. Antwerp), was knighted by Charles the Simple in 916 for a timely gift of ripe strawberries.[3] The Emperor gave the Fraise family (the surname was corrupted as "Frazer") three "fraises" or stalked strawberries for their coat of arms.

Members of the Frazer family emigrated to Scotland as members of the retinue of the French ambassador, who had been sent by Henry I of France as a gesture of friendship to Malcolm III of Scotland, the vanquisher of Macbeth. For the services against the invading Danes, King Máel Coluim (Malcolm) rewarded the Frazers with grants of land and a coat of arms – which contained the original crest of three strawberries (see Clan Fraser).

Édouard Frazer returned to France from Edinburgh around 1500 to escape Scottish political troubles, taking refuge in Amsterdam. The son of Édouard was Charles-Simon, who settled in France. Charles-Simon's descendants later settled in Savoy.

Youth and education

Amédée-François Frézier was born in Chambéry, Savoy, in 1682. Frézier's father, Pierre-Louis Frézier, a distinguished attorney of law, professor, and advisor to the Duke of Savoy at Chambéry, intended his son to follow him in the law. However, Frézier resisted this career path and was sent instead to study science and theology at Paris. His thesis was entitled Treatise on Navigation and the Elements of Astronomy. After completing his scientific studies, Frézier traveled to Italy where he studied art and architecture –interests he later applied to his study of fortresses and defense structures. He returned to France around 1700 and accepted a lieutenantship in an infantry regiment.

Treatise on Fireworks

Frézier's post gave him enough leisure time to publish his Traité des feux d'artifice pour le spectacle (1706, revised 1747) (Treatise on Fireworks). In this treatise, Frézier studied the recreational and ceremonial uses of fireworks – and pyrotechnics in general, rather than their military uses. Frézier surveyed earlier works on the subject. As Frézier included also instructions for the manufacture of decorative fireworks, the book became a standard text for fireworks makers.

Frezier's Treatise on Fireworks earned its author a transfer to the military intelligence corps, as military engineer for Saint-Malo.

Work in South America

Frézier's superior officers, impressed by his competence, recommended that Frézier be the one to receive the assignment of studying the defense fortifications of Chile and Peru.

Frézier was a lieutenant-colonel of the French Army Intelligence Corps when on January 7, 1712, he was dispatched to South America, four months after the return from the same continent of Louis Feuillée. The goal of Frezier's reconnaissance mission seems to have included making hydrographical observations, correcting existing charts, and taking exact plans of the most important ports and fortresses along the coasts. Frézier ended up disagreeing with Feuillée in regards to the latter's measurement of the latitudes and longitudes of the South American coast and of the principal ports of Chile and Peru. Frézier actually pointed out several mistakes in Feuillée's Relation, which led to a bitter feud between the two travelers.

Sailing aboard the St. Joseph, an armed merchant ship, for about five months, he arrived in Concepción, Chile, on June 16, 1712, after rounding Cape Horn.

Passing himself off as a trader or merchant captain, he could visit the fortifications as a tourist. Frézier ingratiated himself with the Spanish Governors, and based in Concepción, sketched maps of the ports that showed the best approaches for attack, where ammunition was stored and the routes of escape, estimated the strength of the Spanish colonial governments, the living conditions for Indigenous people in these colonies, and examined the Spanish gold and silver mines. He also reported on the operations of the Church, the physical geography and flora and fauna of the area, as well as its agricultural products – such as the species of strawberry that he would subsequently introduce to Europe. About the beach strawberry, Frézier wrote: "They there cultivate entire fields of a type of strawberry differing from ours by their rounder leaves, being fleshier and having strong runners. Its fruit are usually as large as a whole walnut, and sometimes as a small egg. They are of a whitish-red colour and a little less delicate to the taste than our woodland strawberries."

Relation du voyage de la Mer du Sud

All of this was valuable information, which was immediately translated into other major European languages after its first appearance in French as Relation du voyage de la mer du Sud, aux côtes du Chili, du Pérou et de Brésil, fait pendant les années 1712, 1713, et 1714. Frézier's account of his travels in South America was published in Paris in 1716[4][5][6] (2d ed., enlarged, 1732). It was published in England in 1717 as A Voyage to the South-Sea, And along the Coasts of Chili and Peru, In the Years 1712, 1713, and 1714, which included a supplement by Edmund Halley. A Dutch translation appeared in Amsterdam in 1718 and a German translation appeared in Hamburg in 1718.

Additional works included his Réponse au P. Feuillée, which was added to the Paris edition of 1832. Frézier also published a Lettre concernant l'histoire des tremblements de terre de Lima ("Letter concerning the history of earthquakes in Lima") (1755).

Awards and return to the New World

Frézier left Concepción on February 19, 1714, and reached Marseilles on August 17. Upon his return, he was allowed to present his maps to King Louis XIV, who awarded Frézier with 1,000 écus from the royal treasury.

In 1719, Frézier returned to the New World as Engineer-in-Chief to Hispaniola (Santo Domingo) on a two-year assignment to fortify the island. He made a map of the island, and also a plan of the City of Santo Domingo. He suffered from malaria there, but was only allowed to return to Europe in 1728.

On his return, he received the cross of St. Louis. He was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences in 1752.

Work in Europe

Upon his return to Europe, Frézier was sent to Philippsburg and then to Landau, where he built twenty-six defense structures.

Frézier wrote a work that applied the theories of architecture to practical engineering, called La Théorie et la Pratique de la Coupe des Pierres et des Bois pour la Construction des Voûtes et autre Parties des Bâtimens Civils & Militaires, ou Traité de Stéréotomie à l'Usage de l'Architecture (Doulsseker; Paris: L.H. Guerin, 1737-38-39) (The theory and practice of cutting stones and wood for the construction of vaults and other parts of civil and military buildings, or treatise on stereotomy in architectural usage). This work was the standard text on the subject of stone cutting, outlining the principles of three-dimensional geometry. Frézier illustrates complicated intersections between forms such as spheres and cones. He also examines actual building problems, and analyzes complex vaults.

He also married, and was commissioned as a captain. In 1739, he was named Director of Fortifications for the whole of Brittany.

In 1764, he retired from service, but still maintained an interest in various subjects, including desalinization, architecture, navigation, and landing methods for the Isles Lucayes (the Bahamas). It is said he made himself read at least six hours a day, especially books on travel and history.

He died in Brest.

See also

References

- International Plant Names Index. Frez.

- "Chapter 4: The Strawberry From Chile". www.nal.usda.gov. Archived from the original on 1999-11-09.

- Archived 2009-02-13 at the Wayback Machine, pg.27-28

- Sabin, Joseph (1875). A Dictionary of Books Relating to America, from Its Discovery to the Present Time: Franklin to Hall. Vol. 7. New York: J. Sabin & Sons. p. 65. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- "Frézier, Amédée François 1682-1773". WorldCat. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Heawood, Edward (2012). A History of Geographical Discovery: In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. p. 206. ISBN 9781107600492. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

External links

- Digitized copy of the German translation of "Relation du voyage de la mer du Sud aux côtes du Chili, du Pérou, et du Brésil" (Hamburg: 1718) via John Carter Brown Library on Internet Archive

- G.M. Darrow, The Strawberry: History, Breeding and Physiology Archived 2009-02-13 at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- History of the Strawberry (in English)

- "Amédée François Frézier discovered the Chilean strawberry" (in English)

Gallery

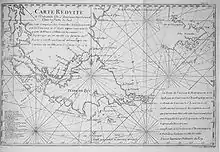

Hispaniola (1724)

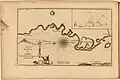

Hispaniola (1724) Strait of Magellan, Chile (1717)

Strait of Magellan, Chile (1717) Baía de Todos os Santos, Brazil (1717)

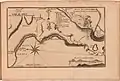

Baía de Todos os Santos, Brazil (1717) Concepción, Chile (1717)

Concepción, Chile (1717) Copiapó, Chile (1717)

Copiapó, Chile (1717) Coquimbo, Chile (1717)

Coquimbo, Chile (1717) Le Maire Strait (1717)

Le Maire Strait (1717) Ilo, Peru (1717)

Ilo, Peru (1717) Valparaíso, Chile (1717)

Valparaíso, Chile (1717) Pisco, Peru (1717)

Pisco, Peru (1717) St. Vincent, Cape Verde (1717)

St. Vincent, Cape Verde (1717) Callao, Peru (1717)

Callao, Peru (1717) Frontispiece of A voyage to the South-sea.. (1717)

Frontispiece of A voyage to the South-sea.. (1717) São Salvador de Bahia de Todos os Santos, Brazil (1717)

São Salvador de Bahia de Todos os Santos, Brazil (1717) Title Page of A voyage to the South sea... (1717)

Title Page of A voyage to the South sea... (1717) Valparaíso, Chile (1717)

Valparaíso, Chile (1717) Arica, Chile (1717)

Arica, Chile (1717) Callao, Peru (1717)

Callao, Peru (1717) La Serena, Chile (1717)

La Serena, Chile (1717)