Amash–Conyers Amendment

The Amash–Conyers Amendment was a proposal to end the "NSA's blanket collection of Americans' telephone records", sponsored by Justin Amash and John Conyers in the US House of Representatives.[1] The measure was voted down, 217 to 205.

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An amendment to end authority for the blanket collection of records under the Patriot Act. It would also bar the NSA and other agencies from using Section 215 of the Patriot Act to collect records, including telephone call records, that pertain to persons who are not subject to an investigation under Section 215. |

|---|---|

| Announced in | the 113th United States Congress |

| Sponsored by | Justin Amash (R–MI) , John Conyers (D–MI) |

Background

In the wake of the 2013 surveillance disclosures, members of the House considered a reform amendment that would limit bulk data collection.

Conyers described his reactions to the disclosures as saying "It was shocking and disappointing that we went this far. I'm not happy about it."[2][3]

Proposed amendment

The proposal was to amend the 2014 National Defense Authorization Act.[4] According to Amash, the amendment:[1][5]

- "sought to bar the NSA and other agencies from using Section 215 of the Patriot Act to collect records", thereby ending the mass surveillance of Americans. Instead, it permitted "the FISA court under Sec. 215 to order the production of records that pertain only to a person under investigation".

- would have permitted the continued use of business records and other "tangible things" if the data were "actually related to an authorized counter-terrorism investigation".

- would have required judicial oversight with "a substantive, statutory standard to apply to make sure the NSA does not violate Americans' civil liberties".

Opposition

Notable opposition to the amendment came from Mike Rogers (R-MI) and Dutch Ruppersberger (D-MD), the senior leaders of the House Intelligence Committee, and from the administration of President Barack Obama.[2] The Obama administration statement criticized the amendment for being a "blunt approach", saying "We urge the House to reject the Amash amendment and instead move forward with an approach that appropriately takes into account the need for a reasoned review of what tools can best secure the nation."[2][6] General Keith Alexander, the director of the NSA, gave an "emergency" four-hour briefing for House members in which he "implored legislators that preventing his agency from collecting the phone records on millions of Americans would have dire consequences for national security."[6][7]

Vote

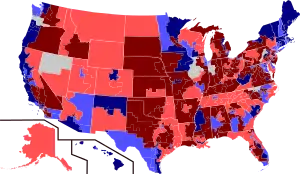

On July 24, 2013, the amendment was considered by the House of Representatives. The measure was "narrowly defeated" by a vote of 217 to 205.[2][8][9]

The vote was noticed for its unusual split, described as "one of the most unusual votes taken in the House in a long time."[10] It garnered both bi-partisan support and bi-partisan opposition: 94 Republicans and 111 Democrats voted for the amendment. It was opposed by 134 Republicans and 83 Democrats.[11] House leaders from both parties opposed the amendment.[6] The Republican and Democratic leaders of the House Intelligence Committee released a joint statement opposing the amendment, arguing it would have "eliminated a crucial counterterrorism tool".[6][12][13] 12 members (6 Republicans and 6 Democrats) did not vote on the amendment.[14]

An analysis indicated that those who voted against the amendment received 122% more in campaign contributions from defense contractors than those who voted in favor.[15]

List of votes

- Justin Amash (R-MI)

- Mark Amodei (R-NV)

- Spencer Bachus (R-AL)

- Joe Barton (R-TX)

- Karen Bass (D-CA)

- Xavier Becerra (D-CA)

- Kerry Bentivolio (R-MI)

- Rob Bishop (R-UT)

- Diane Black (R-TN)

- Marsha Blackburn (R-TN)

- Earl Blumenauer (D-OR)

- Suzanne Bonamici (D-OR)

- Bob Brady (D-PA)

- Bruce Braley (D-IA)

- Jim Bridenstine (R-OK)

- Paul Broun (R-GA)

- Vern Buchanan (R-FL)

- Michael C. Burgess (R-TX)

- Lois Capps (D-CA)

- Mike Capuano (D-MA)

- Tony Cárdenas (D-CA)

- André Carson (D-IN)

- Matt Cartwright (D-PA)

- Bill Cassidy (R-LA)

- Steve Chabot (R-OH)

- Jason Chaffetz (R-UT)

- Judy Chu (D-CA)

- David Cicilline (D-RI)

- Yvette Clarke (D-NY)

- Bill Clay (D-MS)

- Emanuel Cleaver (D-MO)

- Jim Clyburn (D-SC)

- Mike Coffman (R-CO)

- Steve Cohen (D-TN)

- Gerry Connolly (D-VA)

- John Conyers (D-MI)

- Joe Courtney (D-CT)

- Kevin Cramer (R-ND)

- Joseph Crowley (D-NY)

- Elijah Cummings (D-MD)

- Steve Daines (R-MT)

- Danny K. Davis (D-IL)

- Rodney L. Davis (R-IL)

- Peter DeFazio (D-OR)

- Diana DeGette (D-CO)

- Rosa DeLauro (D-CT)

- Suzan DelBene (D-WA)

- Ron DeSantis (R-FL)

- Scott DesJarlais (R-TN)

- Ted Deutch (D-FL)

- John Dingell (D-MI)

- Lloyd Doggett (D-TX)

- Michael F. Doyle (D-PA)

- Sean Duffy (R-WI)

- Jeff Duncan (R-SC)

- Jimmy Duncan (R-TN)

- Donna Edwards (D-MD)

- Keith Ellison (D-MN)

- Anna Eshoo (D-CA)

- Blake Farenthold (R-TX)

- Sam Farr (D-CA)

- Chaka Fattah (D-PA)

- Stephen Fincher (R-TN)

- Mike Fitzpatrick (R-PA)

- Chuck Fleischmann (R-TN)

- John Fleming (R-LA)

- Marcia Fudge (D-OH)

- Tulsi Gabbard (D-HI)

- John Garamendi (D-CA)

- Cory Gardner (R-CO)

- Scott Garrett (R-NJ)

- Chris Gibson (R-NY)

- Louie Gohmert (R-TX)

- Paul Gosar (R-AZ)

- Trey Gowdy (R-SC)

- Tom Graves (R-GA)

- Alan Grayson (D-FL)

- Gene Green (D-TX)

- Tim Griffin (R-AR)

- Morgan Griffith (R-VA)

- Raúl Grijalva (D-AZ)

- Janice Hahn (D-CA)

- Ralph Hall (R-TX)

- Andy Harris (R-MD)

- Alcee Hastings (D-FL)

- Rush Holt Jr. (D-NJ)

- Mike Honda (D-CA)

- Tim Huelskamp (R-KS)

- Jared Huffman (D-CA)

- Bill Huizenga (R-MI)

- Randy Hultgren (R-IL)

- Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY)

- Lynn Jenkins (R-KS)

- Bill Johnson (R-OH)

- Walter B. Jones Jr. (R-NC)

- Jim Jordan (R-OH)

- William R. Keating (D-MA)

- Dan Kildee (D-MI)

- Jack Kingston (R-GA)

- Raúl Labrador (R-ID)

- Doug LaMalfa (R-CA)

- Doug Lamborn (R-CO)

- John B. Larson (D-CT)

- Barbara Lee (D-CA)

- John Lewis (D-GA)

- David Loebsack (D-IA)

- Zoe Lofgren (D-CA)

- Alan Lowenthal (D-CA)

- Michelle Lujan Grisham (D-NM)

- Ben Luján (D-NM)

- Cynthia Lummis (R-WY)

- Stephen Lynch (D-MA)

- Dan Maffei (D-NY)

- Carolyn Maloney (D-NY)

- Kenny Marchant (R-TX)

- Thomas Massie (R-KY)

- Doris Matsui (D-CA)

- Tom McClintock (R-CA)

- Betty McCollum (D-MN)

- Jim McDermott (D-WA)

- Jim McGovern (D-MA)

- Patrick McHenry (R-NC)

- Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA)

- Mark Meadows (R-NC)

- John Mica (R-FL)

- Mike Michaud (D-ME)

- Gary Miller (R-CA)

- George Miller (D-CA)

- Gwen Moore (D-WI)

- Jim Moran (D-VA)

- Markwayne Mullin (R-OK)

- Mick Mulvaney (R-SC)

- Jerrold Nadler (D-NY)

- Grace Napolitano (D-CA)

- Richard Neal (D-MA)

- Rick Nolan (D-MN)

- Rich Nugent (R-FL)

- Beto O'Rourke (D-TX)

- Bill Owens (D-NY)

- Bill Pascrell (D-NJ)

- Ed Pastor (D-AZ)

- Steve Pearce (R-NM)

- Ed Perlmutter (D-CO)

- Scott Perry (R-PA)

- Tom Petri (R-WI)

- Chellie Pingree (D-ME)

- Mark Pocan (D-WI)

- Ted Poe (R-TX)

- Jared Polis (D-CO)

- Bill Posey (R-FL)

- Tom Price (R-GA)

- Trey Radel (R-FL)

- Nick Rahall (D-WV)

- Charles Rangel (D-NY)

- Reid Ribble (R-WI)

- Tom Rice (R-SC)

- Cedric Richmond (D-LA)

- Phil Roe (R-TN)

- Dana Rohrabacher (R-CA)

- Dennis Ross (R-FL)

- Keith Rothfus (R-PA)

- Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA)

- Bobby Rush (D-IL)

- Matt Salmon (R-AZ)

- Linda Sánchez (D-CA)

- Loretta Sanchez (D-CA)

- Mark Sanford (R-SC)

- John Sarbanes (D-MD)

- Steve Scalise (R-LA)

- Adam Schiff (D-CA)

- Kurt Schrader (D-OR)

- David Schweikert (R-AZ)

- Bobby Scott (D-VA)

- Jim Sensenbrenner (R-WI)

- José E. Serrano (D-NY)

- Carol Shea-Porter (D-NH)

- Brad Sherman (D-CA)

- Chris Smith (R-NJ)

- Jason T. Smith (R-MO)

- Steve Southerland (R-FL)

- Jackie Speier (D-CA)

- Chris Stewart (R-UT)

- Steve Stockman (R-TX)

- Eric Swalwell (D-CA)

- Mark Takano (D-CA)

- Bennie Thompson (D-MS)

- Glenn Thompson (R-PA)

- John F. Tierney (D-MA)

- Scott Tipton (R-CO)

- Paul Tonko (D-NY)

- Niki Tsongas (D-MA)

- Filemon Vela Jr. (D-TX)

- Nydia Velázquez (D-NY)

- Tim Walz (D-MN)

- Maxine Waters (D-CA)

- Mel Watt (D-NC)

- Henry Waxman (D-CA)

- Randy Weber (R-TX)

- Peter Welch (D-VT)

- Roger Williams (R-TX)

- Joe Wilson (R-SC)

- John Yarmuth (D-KY)

- Kevin Yoder (R-KS)

- Ted Yoho (R-FL)

- Don Young (R-AK)

- Robert Aderholt (R-AL)

- Rodney Alexander (R-LA)

- Rob Andrews (D-NJ)

- Michele Bachmann (R-MN)

- Ron Barber (D-AZ)

- Andy Barr (R-KY)

- John Barrow (D-GA)

- Dan Benishek (R-MI)

- Ami Bera (D-CA)

- Gus Bilirakis (R-FL)

- Sanford Bishop (D-GA)

- Tim Bishop (D-NY)

- John Boehner (R-OH)

- Jo Bonner (R-AL)

- Charles Boustany (R-LA)

- Kevin Brady (R-TX)

- Mo Brooks (R-AL)

- Susan Brooks (R-IN)

- Corrine Brown (D-FL)

- Julia Brownley (D-CA)

- Larry Bucshon (R-IN)

- G. K. Butterfield (D-NC)

- Ken Calvert (R-CA)

- David Camp (R-MI)

- Eric Cantor (R-VA)

- Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV)

- John Carney (D-DE)

- John Carter (R-TX)

- Kathy Castor (D-FL)

- Joaquín Castro (D-TX)

- Tom Cole (R-OK)

- Doug Collins (R-GA)

- Chris Collins (R-NY)

- Mike Conaway (R-TX)

- Paul Cook (R-CA)

- Jim Cooper (D-TN)

- Jim Costa (D-CA)

- Tom Cotton (R-AR)

- Rick Crawford (R-AR)

- Ander Crenshaw (R-FL)

- Henry Cuellar (D-TX)

- John Culberson (R-TX)

- Danny K. Davis (D-CA)

- John Delaney (D-MD)

- Jeff Denham (R-CA)

- Charlie Dent (R-PA)

- Mario Díaz-Balart (R-FL)

- Tammy Duckworth (D-IL)

- Renee Ellmers (R-NC)

- Eliot Engel (D-NY)

- William Enyart (D-IL)

- Elizabeth Esty (D-CT)

- Bill Flores (R-TX)

- Randy Forbes (R-VA)

- Jeff Fortenberry (R-NE)

- Bill Foster (D-IL)

- Virginia Foxx (R-NC)

- Lois Frankel (D-FL)

- Trent Franks (R-AZ)

- Rodney Frelinghuysen (R-NJ)

- Pete Gallego (D-TX)

- Joe Garcia (D-FL)

- Jim Gerlach (R-PA)

- Bob Gibbs (R-OH)

- Phil Gingrey (R-GA)

- Bob Goodlatte (R-VA)

- Kay Granger (R-TX)

- Sam Graves (R-MO)

- Al Green (D-TX)

- Michael Grimm (R-NY)

- Brett Guthrie (R-KY)

- Luis Gutiérrez (D-IL)

- Colleen Hanabusa (D-HI)

- Richard L. Hanna (R-NY)

- Gregg Harper (R-MS)

- Vicky Hartzler (R-MO)

- Doc Hastings (R-WA)

- Joe Heck (R-NV)

- Dennis Heck (D-WA)

- Jeb Hensarling (R-TX)

- Brian Higgins (D-NY)

- Jim Himes (D-CT)

- Rubén Hinojosa (D-TX)

- George Holding (R-NC)

- Steny Hoyer (D-MD)

- Richard Hudson (R-NC)

- Duncan D. Hunter (R-CA)

- Robert Hurt (R-VA)

- Steve Israel (D-NY)

- Darrell Issa (R-CA)

- Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX)

- Hank Johnson (D-GA)

- Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX)

- Sam Johnson (R-TX)

- David Joyce (R-OH)

- Marcy Kaptur (D-OH)

- Robin Kelly (D-IL)

- Mike Kelly (R-PA)

- Joseph P. Kennedy III (D-MA)

- Derek Kilmer (D-WA)

- Ron Kind (D-WI)

- Steve King (R-IA)

- Peter T. King (R-NY)

- Adam Kinzinger (R-IL)

- Ann Kirkpatrick (D-AZ)

- John Kline (R-MN)

- Ann McLane Kuster (D-NH)

- Leonard Lance (R-NJ)

- Jim Langevin (D-RI)

- James Lankford (R-OK)

- Rick Larsen (D-WA)

- Tom Latham (R-IA)

- Bob Latta (R-OH)

- Sander Levin (D-MI)

- Dan Lipinski (D-IL)

- Frank LoBiondo (R-NJ)

- Billy Long (R-MO)

- Nita Lowey (D-NY)

- Frank Lucas (R-OK)

- Blaine Luetkemeyer (R-MO)

- Sean Patrick Maloney (D-NY)

- Tom Marino (R-PA)

- Jim Matheson (D-UT)

- Kevin McCarthy (R-CA)

- Michael McCaul (R-TX)

- Mike McIntyre (D-NC)

- Howard McKeon (R-CA)

- David McKinley (R-WV)

- Gloria Negrete McLeod (D-CA)

- Pat Meehan (R-PA)

- Gregory Meeks (D-NY)

- Grace Meng (D-NY)

- Luke Messer (R-IN)

- Jeff Miller (R-FL)

- Candice Miller (R-MI)

- Patrick Murphy (D-FL)

- Timothy F. Murphy (R-PA)

- Randy Neugebauer (R-TX)

- Kristi Noem (R-SD)

- Devin Nunes (R-CA)

- Alan Nunnelee (R-MS)

- Pete Olson (R-TX)

- Steven Palazzo (R-MS)

- Erik Paulsen (R-MN)

- Donald Payne Jr. (D-NJ)

- Nancy Pelosi (D-CA)

- Scott Peters (D-CA)

- Gary Peters (D-MI)

- Collin Peterson (D-MN)

- Robert Pittenger (R-NC)

- Joe Pitts (R-PA)

- Mike Pompeo (R-KS)

- David Price (D-NC)

- Mike Quigley (D-IL)

- Tom Reed (R-NY)

- Dave Reichert (R-WA)

- Jim Renacci (R-OH)

- Scott Rigell (R-VA)

- Martha Roby (R-AL)

- Mike D. Rogers (R-AL)

- Hal Rogers (R-KY)

- Mike Rogers (R-MI)

- Tom Rooney (R-FL)

- Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL)

- Peter Roskam (R-IL)

- Ed Royce (R-CA)

- Raul Ruiz (D-CA)

- Jon Runyan (R-NJ)

- Dutch Ruppersberger (D-MD)

- Tim Ryan (D-OH)

- Paul Ryan (R-WI)

- Jan Schakowsky (D-IL)

- Brad Schneider (D-IL)

- Allyson Schwartz (D-PA)

- Austin Scott (R-GA)

- David Scott (D-GA)

- Pete Sessions (R-TX)

- Terri Sewell (D-AL)

- John Shimkus (R-IL)

- Bill Shuster (R-PA)

- Mike Simpson (R-ID)

- Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ)

- Albio Sires (D-NJ)

- Louise Slaughter (D-NY)

- Adrian Smith (R-NE)

- Lamar S. Smith (R-TX)

- Adam Smith (D-WA)

- Steve Stivers (R-OH)

- Marlin Stutzman (R-IN)

- Lee Terry (R-NE)

- Mike Thompson (D-CA)

- Pat Tiberi (R-OH)

- Dina Titus (D-NV)

- Mike Turner (R-OH)

- Fred Upton (R-MI)

- David Valadao (R-CA)

- Chris Van Hollen (D-MD)

- Juan Vargas (D-CA)

- Marc Veasey (D-TX)

- Pete Visclosky (D-IN)

- Ann Wagner (R-MO)

- Tim Walberg (R-MI)

- Greg Walden (R-OR)

- Jackie Walorski (R-IN)

- Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL)

- Daniel Webster (R-FL)

- Brad Wenstrup (R-OH)

- Lynn Westmoreland (R-GA)

- Ed Whitfield (R-KY)

- Frederica Wilson (D-FL)

- Rob Wittman (R-VA)

- Frank Wolf (R-VA)

- Steve Womack (R-AR)

- Rob Woodall (R-GA)

- Bill Young (R-FL)

- Todd Young (R-IN)

References

- "Amash NSA Amendment Fact Sheet | Congressman Justin Amash". Amash.house.gov. 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- "US House rejects Amash-Conyers amendment on NSA surveillance powers". GlobalPost. 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- Peterson, Andrea (2013-07-24). "Why Rep. John Conyers wants to defund NSA's phone snooping". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- "How Amash Amendment Blocks NSA Spying". Business Insider. 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- "Partisanship and Opportunities for Additional Bipartisanship in Tech Immigration and Privacy Reform". Master's Capstone Projects (UCLA). 2013-12-13.

- Spencer Ackerman in Washington (25 July 2013). "NSA surveillance: narrow defeat for amendment to restrict data collection | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- "NSA's Keith Alexander Calls Emergency Private Briefing To Lobby Against Justin Amash Amendment Curtailing Its Power". Huffingtonpost.com. 2013-07-23. Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- "H.Amdt. 413 (Amash) to H.R. 2397: Amendment sought to end authority for the blanket collection of records under the Patriot ..." GovTrack.us. 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- "Amash-Conyers anti-NSA amendment lost by just 12 votes, 205-217". Americablog.com. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- "Chris Hayes And David Sirota Have 4-Hour Erection Over Amash Amendment". Mediaite. 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- "Mapping the Vote to Limit the NSA via Amash-Conyers Amendment - Hit & Run". Reason.com. 2013-07-25. Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- "Joint Statement by House Intelligence Chairman Mike Rogers and Ranking Member C.A. Dutch Ruppersberger on the Defeat of the Amash Amendment | The Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence". Intelligence.house.gov. 2013-07-24. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- "Joint Statement on the Defeat of the Amash Amendment". democrats.intelligence.house.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- Washington, U. S. Capitol Room H154; p:225-7000, DC 20515-6601 (2013-07-24). "Roll Call 412 Roll Call 412, Bill Number: H. R. 2397, 113th Congress, 1st Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved 2021-07-02.

- Kravets, David (July 26, 2013). "Lawmakers Who Upheld NSA Phone Spying Received Double the Defense Industry Cash". Retrieved August 3, 2013.