Regionalism (art)

American Regionalism is an American realist modern art movement that included paintings, murals, lithographs, and illustrations depicting realistic scenes of rural and small-town America primarily in the Midwest. It arose in the 1930s as a response to the Great Depression, and ended in the 1940s due to the end of World War II and a lack of development within the movement. It reached its height of popularity from 1930 to 1935, as it was widely appreciated for its reassuring images of the American heartland during the Great Depression.[1] Despite major stylistic differences between specific artists, Regionalist art in general was in a relatively conservative and traditionalist style that appealed to popular American sensibilities, while strictly opposing the perceived domination of French art.[2]

Rise

Before World War II, the concept of Modernism was not clearly defined in the context of American art. There was also a struggle to define a uniquely American type of art.[3] On the path to determining what American art would be, some American artists rejected the modern trends emanating from the Armory Show and European influences particularly from the School of Paris. By rejecting European abstract styles, American artists chose to adopt academic realism, which depicted American urban and rural scenes. Partly due to the Great Depression, Regionalism became one of the dominant art movements in America in the 1930s, the other being Social Realism. At the time, the United States was still a heavily agricultural nation, with a much smaller portion of its population living in industrial cities such as New York City or Chicago.

American Scene Painting

American Scene Painting is an umbrella term for American Regionalism and Social Realism otherwise known as Urban Realism. Much of American Scene Painting conveys a sense of nationalism and romanticism in depictions of everyday American life. This sense of nationalism stemmed from artists' rejection of modern art trends after World War I and the Armory Show. During the 1930s, these artists documented and depicted American cities, small towns, and rural landscapes; some did so as a way to return to a simpler time away from industrialization, whereas others sought to make a political statement and lent their art to revolutionary and radical causes. The works which stress local and small-town themes are often called "American Regionalism", and those depicting urban scenes, with political and social consciousness are called "Social Realism".[4][5] The version that developed in California is known as California Scene Painting.

Regionalist Triumvirate

American Regionalism is best known through its "Regionalist Triumvirate" consisting of the three most highly respected artists of America's Great Depression era: Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Steuart Curry. All three studied art in Paris, but devoted their lives to creating a truly American form of art. They believed that the solution to urban problems in American life and the Great Depression was for the United States to return to its rural, agricultural roots.[4]

Grant Wood

Wood, from Anamosa, Iowa, is best known for his painting American Gothic. He also wrote a notable pamphlet titled Revolt Against the City, published in Iowa City in 1935, in which he asserted that American artists and buyers of art were no longer looking to Parisian culture for subject matter and style. Wood wrote that Regional artists interpret the physiography, industry, and psychology of their hometown and that the competition of these preceding elements create American culture. He wrote that the lure of the city was gone, and hoped that part of the widely diffused "whole people" would prevail. He cited Thomas Jefferson's characterization of cities as "ulcers on the body politic."[6]

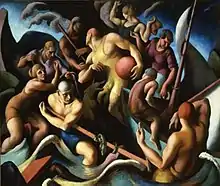

Thomas Hart Benton

Benton was a painter, illustrator, and lithographer from Neosho, Missouri, who became widely known for his murals. His subject matter mostly focused on working-class America, while incorporating social criticism. He heavily denounced European modern art despite the fact that he was regarded as a modernist and an abstractionist. When Regionalism lost its popularity in America, Benton got a job as a teacher at the Kansas City Art Institute, where he became a teacher and lifelong father figure for Jackson Pollock. Benton wrote two autobiographies, his first one titled An Artist in America, which described his travels in the United States, and his second, An American in Art, which described his technical development as an artist. Along with being a painter, he was a talented folk musician, and released a record called Saturday Night at Tom Benton's.[7]

John Steuart Curry

Curry, from Dunavant, Kansas, began as an illustrator of "Wild West" stories, but after more training, he was hired to paint murals for the Department of Justice and the Department of Interior under the Federal Arts Patronage in the New Deal.[8] He had a histrionic, anecdotal style, and believed that art should come from everyday life and that artists should paint what they love. In his case he painted his beloved home in the Midwest.[9] Wood wrote about Curry's style and subject matter of art, stating "It was action he loved most to interpret: the lunge through space, the split second before the kill, the suspended moment before the storm strikes."[10]

American Modernism

A debate over who and what would define American art as Modernism began with the 1913 Armory Show in New York between abstraction and realism. The debate then evolved in the 1930s into the three camps, Regionalism, Social Realism, and abstract art. By the 1940s, Regionalism and Social Realism were placed on the same side of the debate as American Scene Painting, leaving only two camps, that were divided geographically and politically. American Scene Painting was promoted by conservative, anti-Modernist critics such as Thomas Craven, who saw it as a way to defeat the influence of abstraction arriving from Europe. American Scene painters primarily lived in rural areas and created works that were realistic and addressed social, economic and political issues. On the other side of the debate were the abstract artists who primarily lived in New York City and were promoted by pro-Modernist critics, writers and artists such as Alfred Stieglitz.

Decline

When World War II ended, Regionalism and Social Realism lost status in the art world. The end of World War II ushered in a new era of peace and prosperity, and the Cold War brought a change in the political perception of Americans and allowed Modernist critics to gain power. Regionalism and Social Realism also lost popularity among American viewers due to a lack of development within the movement due to the tight constraints of the art to agrarian subject matter. Ultimately, this led to abstract expressionism winning out the title of American Modernism, and becoming the new prominent and popular artistic movement.[11]

Importance

Regionalism limited the spread of abstract art to the East Coast, which allowed American art to gain confidence in itself instead of relying on European styles.[12] With American art fully established, Regionalism then was able to bridge the gap between abstract art and academic realism similarly to how the Impressionists bridged a gap for the Post-Impressionists, like Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin, in France a generation earlier. Despite the fact that Regionalism developed with the intent of replacing European abstraction with authentic American realism, it became the bridge for American Abstract Expressionism, led by Benton's pupil Jackson Pollock.[12] Pollock's power as an artist was mostly due to the encouragement and influence of Thomas Hart Benton.[11]

Influence

Norman Rockwell and Andrew Wyeth were the primary successors to Regionalism's natural realism. Rockwell became widely popular with his illustrations of the American family in magazines. Wyeth on the other hand painted Christina's World, which competes with Wood's American Gothic for the title of America's favorite painting.[12]

Regionalism has had a strong and lasting influence on popular culture, particularly in America. It has given America some of its most iconic pieces of art that symbolize the country. Regionalist-type imagery influenced many American children's book illustrators such as Holling Clancy Holling, and still shows up in advertisements, movies, and novels today. Works like American Gothic are commonly parodied around the world. Even John Steuart Curry's mural, Tragic Prelude, which is painted on a wall at the Kansas State Capitol, was featured on the cover of American progressive rock band Kansas' debut album titled Kansas.[13]

Norman Rockwell's Freedom from Want, 1943, was painted during the middle of the United States' involvement in World War II. The painting is comparable with the traditional American Thanksgiving dinner. During this time families around the United States were having to ration food, their sons were sent to fight overseas, and war bonds were being sold by the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Taking inspiration from President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Four Freedoms: State of the Union Address from January 1941, Rockwell would create this work that would be used as propaganda. It would be transformed into prints and appear in four issues of the Saturday Evening Post during 1943, and would be used by the U.S. Department of the Treasury to encourage the selling of war bonds. Through this he was able to reach a much greater audience than many other Regionalist painters would be able to in their time.[14]

Notable paintings

- American Gothic painted by Grant Wood in 1930, now on display at the Art Institute of Chicago. He found inspiration in a Carpenter Gothic-style farm house in Eldon, Iowa, and used his dentist and sister as models for the people.

- Baptism in Kansas painted by John Steuart Curry in 1926, and since 1931 has belonged to the Whitney Museum of American Art. The painting was based on a scene Curry witnessed in 1915 when the creeks were dried up and the only suitable method for baptism was the water tank.

- The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere painted by Grant Wood in 1931, since been sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, although it has not been on view since 2017. Woods was inspired by the poem "Paul Revere's Ride" by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

- Freedom from Want painted by Norman Rockwell in 1943, now a part of the Norman Rockwell Museums permanent collection in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Rockwell was inspired to paint this, one of a series of four paintings known as the Four Freedoms Series, by United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1941 State of the Union Address, known as Four Freedoms.

Notable artists

- Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975)

- John Rogers Cox (1915–1990)

- John Steuart Curry (1897–1946)

- Margot Peet (1903–1995)

- Edna Reindel (1894–1990)

- Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

- Grant Wood (1891–1942)

- Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009)

References

- "Regionalism". Oxford Art Online. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- "Regionalism". The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- Corn, Wanda (1999). The Great American Think. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520231993.

- "American Scene Painting – American Regoionalism and Social Realism". www.arthistoryarchive.com. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- Baigell, Matthew (1974). The American Scene: American Painting of the 1930s. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-46620-5.

- Wood, Grant (1935). Revolt Against the City. Iowa City: Clio Press.

- "Benton, Thomas Hart". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- "Curry, John Steuart". Oxford Art Online. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- "Curry, John Steuart". The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- "Hogs Killing a Snake | The Art Institute of Chicago". www.artic.edu. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- "Collections". www.siouxcityartcenter.org. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- "Regionalism: Mid-West American Scene Painting". www.visual-arts-cork.com. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- "Kansas State Capitol – Online tour – Tragic Prelude – Kansas Historical Society". www.kshs.org. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- "American Regionalism - Important Paintings". The Art Story. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

.jpg.webp)