Anaerobic oxidation of methane

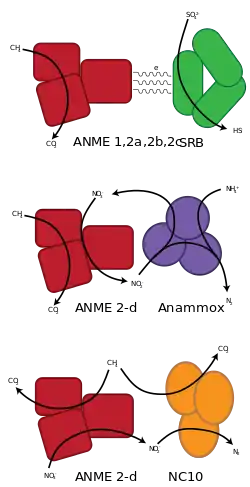

Anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) is a methane-consuming microbial process occurring in anoxic marine and freshwater sediments. AOM is known to occur among mesophiles, but also in psychrophiles, thermophiles, halophiles, acidophiles, and alkophiles.[1] During AOM, methane is oxidized with different terminal electron acceptors such as sulfate, nitrate, nitrite and metals, either alone or in syntrophy with a partner organism.[2]

Coupled to sulfate reduction

The overall reaction is:

- CH4 + SO42− → HCO3− + HS− + H2O

Sulfate-driven AOM is mediated by a syntrophic consortium of methanotrophic archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria.[7] They often form small aggregates or sometimes voluminous mats. The archaeal partner is abbreviated ANME, which stands for "anaerobic methanotroph". ANME's are very closely related to methanogenic archaea and recent investigations suggest that AOM is an enzymatic reversal of methanogenesis.[8] It is still poorly understood how the syntrophic partners interact and which intermediates are exchanged between the archaeal and bacterial cell. The research on AOM is hindered by the fact that the responsible organisms have not been isolated. This is because these organisms show very slow growth rates with a minimum doubling time of a few months. Countless isolation efforts have not been able to isolate one of the anaerobic methanotrophs, a possible explanation can be that the ANME archaea and the SRB have an obligate syntrophic interaction and can therefore not be isolated individually.

In benthic marine areas with strong methane releases from fossil reservoirs (e.g. at cold seeps, mud volcanoes or gas hydrate deposits) AOM can be so high that chemosynthetic organisms like filamentous sulfur bacteria (see Beggiatoa) or animals (clams, tube worms) with symbiont sulfide-oxidizing bacteria can thrive on the large amounts of hydrogen sulfide that are produced during AOM. The bicarbonate (HCO3−) produced from AOM can (i) get sequestered in the sediments by the precipitation of calcium carbonate or so-called methane-derived authigenic carbonates [9] and (ii) get released to the overlying water column.[10] Methane-derived authigenic carbonates are known to be the most 13C depleted carbonates on Earth, with δ13C values as low as -125 per mil PDB reported.[11]

Coupled to nitrate and nitrite reduction

The overall reactions are:

- CH4 + 4 NO3− → CO2 + 4 NO2− + 2 H2O

- 3 CH4 + 8 NO2− + 8 H+ → 3 CO2 + 4 N2 + 10 H2O

Recently, ANME-2d is shown to be responsible nitrate-driven AOM.[5] The ANME-2d, named Methanoperedens nitroreducens, is able to perform nitrate-driven AOM without a partner organism via reverse methanogenesis with nitrate as the terminal electron acceptor, using genes for nitrate reduction that have been laterally transferred from a bacterial donor. This was also the first complete reverse methanogenesis pathway including the mcr and mer genes.

In 2010, omics, especially metagenomics, analysis showed that nitrite reduction can be coupled to methane oxidation by a single bacterial species Candidatus Methylomirabilis oxyfera (phylum NC10), without the need for an archaeal partner.[12]

Environmental relevance

AOM is considered to be a very important process reducing the emission of the greenhouse gas methane from the ocean into the atmosphere. It is estimated that almost 80% of all the methane that arises from marine sediments is oxidized anaerobically by this process.[13]

See also

References

- Dunfield, Peter F. (2009), "Methanotrophy in Extreme Environments", eLS, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0021897, ISBN 978-0-470-01590-2, retrieved 2021-11-19

- Reimann, Joachim; Jetten, Mike S.M.; Keltjens, Jan T. (2015). "Chapter 7, Section 4 Enzymes in Nitrite-driven Methane Oxidation". In Peter M.H. Kroneck; Martha E. Sosa Torres (eds.). Sustaining Life on Planet Earth: Metalloenzymes Mastering Dioxygen and Other Chewy Gases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 15. Springer. pp. 281–302. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12415-5_7. ISBN 978-3-319-12414-8. PMID 25707470.

- McGlynn SE, Chadwick GL, Kempes CP, Orphan VJ (2015). "Single cell activity reveals direct electron transfer in methanotrophic consortia". Nature. 526 (7574): 531–535. Bibcode:2015Natur.526..531M. doi:10.1038/nature15512. PMID 26375009. S2CID 4396372.

- Wegener G, Krukenberg V, Riedel D, Tegetmeyer HE, Boetius A (2015). "Intercellular wiring enables electron transfer between methanotrophic archaea and bacteria". Nature. 526 (7574): 587–590. Bibcode:2015Natur.526..587W. doi:10.1038/nature15733. hdl:21.11116/0000-0001-C3BE-D. PMID 26490622. S2CID 4391386.

- Haroon MF, Hu S, Shi Y, Imelfort M, Keller J, Hugenholtz P, Yuan Z, Tyson GW (2013). "Anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled to nitrate reduction in a novel archaeal lineage". Nature. 500 (7464): 567–70. Bibcode:2013Natur.500..567H. doi:10.1038/nature12375. PMID 23892779. S2CID 4368118.

- Raghoebarsing, A.A.; Pol, A.; van de Pas-Schoonen, K.T.; Smolders, A.J.P.; Ettwig, K.F.; Rijpstra, W.I.C.; et al. (2006). "A microbial consortium couples anaerobic methane oxidation to denitrification". Nature. 440 (7086): 918–921. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..918R. doi:10.1038/nature04617. hdl:1874/22552. PMID 16612380. S2CID 4413069.

- Knittel, K.; Boetius, A. (2009). "Anaerobic oxidation of methane: progress with an unknown process". Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63: 311–334. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093130. hdl:21.11116/0000-0001-CC96-0. PMID 19575572.

- Scheller S, Goenrich M, Boecher R, Thauer RK, Jaun B (2010). "The key nickel enzyme of methanogenesis catalyses the anaerobic oxidation of methane". Nature. 465 (7298): 606–8. Bibcode:2010Natur.465..606S. doi:10.1038/nature09015. PMID 20520712. S2CID 4386931.

- Ritger, Scott A.; Carson, Bobb; Suess, Erwin (1987). "Methane-derived authigenic carbonates formed by subduction-induced pore-water expulsion along the Oregon/Washington margin". GSA Bulletin. 98 (2): 147. Bibcode:1987GSAB...98..147R. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1987)98<147:MACFBS>2.0.CO;2.

- Akam, Sajjad A.; Coffin, Richard; Abudlla, Hussain; Lyons, Timothy (2020). "Dissolved Inorganic Carbon Pump in Methane-Charged Shallow Marine Sediments: State of the Art and New Model Perspectives". Frontiers in Marine Science. 7 (206). doi:10.3389/fmars.2020.00206. ISSN 2296-7745.

- Drake, H.; Astrom, M.E.; Heim, C.; Broman, C.; Astrom, J.; Whitehouse, M.; Ivarsson, M.; Siljestrom, S.; Sjovall, P. (2015). "Extreme 13C depletion of carbonates formed during oxidation of biogenic methane in fractured granite". Nature Communications. 6: 7020. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.7020D. doi:10.1038/ncomms8020. PMC 4432592. PMID 25948095.

- Ettwig KF, Butler MK, Le Paslier D, Pelletier E, Mangenot S, Kuypers MM, Schreiber F, Dutilh BE, Zedelius J, de Beer D, Gloerich J, Wessels HJ, van Alen T, Luesken F, Wu ML, van de Pas-Schoonen KT, Op den Camp HJ, Janssen-Megens EM, Francoijs KJ, Stunnenberg H, Weissenbach J, Jetten MS, Strous M (2010). "Nitrite-driven anaerobic methane oxidation by oxygenic bacteria" (PDF). Nature. 464 (7288): 543–8. Bibcode:2010Natur.464..543E. doi:10.1038/nature08883. PMID 20336137. S2CID 205220000.

- Reebough, William S (2007). "Oceanic Methane Biogeochemistry". Chemical Reviews. 107 (2): 486–513. doi:10.1021/cr050362v. PMID 17261072. S2CID 41852456.

Bibliography

- Dennis D. Coleman; J. Bruno Risatti; Martin Schoell (1981) Fractionation of carbon and hydrogen isotopes by methane-oxidizing bacteria | Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta |Volume 45, Issue 7, July 1981, Pages 1033-1037 |https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(81)90129-0 | abstract