Bambolinetta

Bambolinetta lignitifila is a fossil species of waterfowl from the Late Miocene of Italy, now classified as the sole member of the genus Bambolinetta. First described in 1884 as a typical dabbling duck, it was not revisited until 2014, when a study showed it to be a highly unusual duck species, probably a flightless, wing-propelled diver similar to a penguin.[2]

| Bambolinetta Temporal range: Late Miocene | |

|---|---|

| |

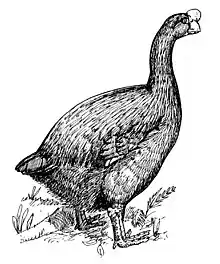

| 1868 figure of the sole specimen[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | †Bambolinetta Mayr & Pavia, 2014 |

| Species: | †B. lignitifila |

| Binomial name | |

| †Bambolinetta lignitifila (Portis, 1884) | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Anas lignitifila Portis, 1884 | |

History

The species is known from partial skeleton collected in Montebamboli, Tuscany, placed in the Museum of Geology and Palaeontology at the University of Turin. Among the other fossils collected from the same locality are some of the hominid Oreopithecus.[2] Tommaso Salvadori was the first to study these fossils, publishing an account as part of an 1868 paper by B. Gastaldi, in which he pointed to similarities with both waterfowl and auks.[1] The species was formally described by Alessandro Portis in 1884,[3] with the name Anas lignitifila, a member of the genus Anas that contains common duck species such as the mallard. Portis cited correspondence with Salvadori, who by then was convinced that the fossil was an anatid; at the time, essentially all fossil ducks were placed in Anas.[2]

After Portis, no studies were made and the only mentions of the species in scientific literature were listings in catalogues;[2] most recently, Jiří Mlíkovský placed the species as incertae sedis (position uncertain) among birds in 2002.[4] The only illustration of the fossil was the lithograph from Gastaldi's 1868 paper, which remains an important documentation of the fossil since much of the distal part of the wing has been lost.[2] The first reexamination of the species was made in a paper by Gerald Mayr and Marco Pavia published in 2014. Mayr and Pavia showed the species to have morphological features not present in any other anatid. According to them, it most likely is a highly unusual anatine, falling outside the three main tribes (Anatini, Mergini and Aythini). Accordingly, they placed the species in its own genus, taking the name Bambolinetta from its type locality.[2]

Description

The sole specimen of the species consists of a partial skeleton on a slab, that includes an incomplete skull, most of the trunk, right wing, parts of the tibiotarsus and tarsometatarsus. This species was probably mid-sized for a duck in life, and had arm bones, in particular the humerus, that are much stouter than those of any other anatids. The ulna is short relative to the humerus and hand, as in auks and penguins. As in the crested auklet, the processus extensorius of the carpometacarpus is well-developed and extends less than it does in other diving birds.[2]

Paleobiology

Bambolinetta appears to have had limited, if any, flight capacities. Mayr and Pavia tentatively suggest that the best explanation for its wing anatomy is that it was a wing-propelled diver, similar to penguins and plotopterids. That would make it the only waterfowl species ever to use wings rather than feet for propulsion in water.[2]

Bambolinetta is known from the MN12 European land mammal age (corresponding to the Middle Turolian period) of the Late Miocene.[2] During this time period, the region that it lived in formed the Tusco-Sardinian island,[5] where in its presumed freshwater habitats, the only predators were crocodilians and otters. The species evolved in the relative absence of terrestrial predators, allowing it to pursue an unorthodox ecological niche. Similar specialisation and loss of flight ability were seen in a number of island waterfowl during the Miocene and Holocene, notably the moa-nalos of Hawaii, Chendytes in modern California, and Cnemiornis in New Zealand.[2]

References

- Gastaldi, B. (1868). "Intorno ad alcuni fossili del Piemonte e della Toscana: Breve nota". Memorie della Reale Accademia delle Scienze di Torino. 2nd series (in Italian). 24: 193–236.

- Mayr, Gerald; Pavia, Marco (2014). "On the true affinities of Chenornis graculoides Portis, 1884, and Anas lignitifila Portis, 1884—an albatross and an unusual duck from the Miocene of Italy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (4): 914–923. Bibcode:2014JVPal..34..914M. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.821076. S2CID 84901071.

- Portis, Alessandro (1884). "Contribuzioni alla ornitolitologia italiana". Memorie della Reale Accademia delle Scienze di Torino. 2nd series (in Italian). 36: 361–384.

- Mlíkovský, Jiří (11 January 2002). Cenozoic Birds of the World. Part 1: Europe (PDF). Praha: Ninox Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2014-11-07. ISBN 80-901105-3-8

- Abbazzi, L.; Delfino, M.; Gallai, G.; Trebini, L.; Rook, L. (2008). "New data on the vertebrate assemblage of Fiume Santo (North-West Sardinia, Italy), and overview on the late Miocene Tusco-Sardinian palaeobioprovince". Palaeontology. 51 (2): 425–451. Bibcode:2008Palgy..51..425A. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00758.x.