Papyrus Anastasi I

Papyrus Anastasi I (officially designated papyrus British Museum 10247)[1] is an ancient Egyptian papyrus containing a satirical text used for the training of scribes during the Ramesside Period (i.e. Nineteenth and Twentieth dynasties). One scribe, an army scribe, Hori, writes to his fellow scribe, Amenemope, in such a way as to ridicule the irresponsible and second-rate nature of Amenemope's work. The papyrus was originally purchased from Giovanni Anastasi in 1839.[2]

Content and importance to modern scholarship

The letter gives examples of what a scribe was supposed to be able to do: calculating the number of rations which have to be doled out to a certain number of soldiers digging a lake, or the quantity of bricks needed to erect a ramp of given dimensions,[3] assessing the number of men needed to move an obelisk or erect a statue, and organizing the supply of provisions for an army. In a long section Hori discusses the geography of the Mediterranean coast as far north as the Lebanon and the troubles which might beset a traveler there.

This papyrus is important to historians and Bible scholars above all for the information it supplies about towns in Syria and Canaan during the New Kingdom.[4] There is a long list of towns which run along the northern border of the djadi or watershed of the Jordan in Canaan, which bound Lebanon along the Litani River and upper retnu and Syria along the Orontes. The border lands of Egypt's province of Caanan with Kadesh are defined on page XIX:

Come let me tell thee of other towns, which are above(??) them. Thou hast not gone to the land of Kadesh, Tekhes, Kurmeren, Temenet, Deper, Idi, Herenem. Thou hast not beheld Kirjath-anab and Beth-Sepher. Thou dost not know Ideren, nor yet Djedpet. Thou dost not know the name of Kheneredj which is in the land of Upe, a bull upon its boundary, the scene of the battles of every warrior. Pray teach me concerning the appearance(?) of Kin; acquaint me with Rehob; explain Beth-sha-el and Tereqel. The stream of Jordan, how is it crossed? Cause me to know the way of crossing over to Megiddo which is above it(??).

— Papyrus Anastasi I, p. XIX[5]

An example of the satire in the text

Hori goes on to show that Amenemope is not skilled in the role of a maher. The word maher is found frequently in this papyrus, but nowhere else. Gardiner suggests it must be the technical name of the Egyptian emissary in Syria.[6]

Hori then relates an imagined anecdote where Amenemope experiences an adventure of a maher.[7] It contains a lot of detail reflecting discreditably on his name and comparing him to Qedjerdi, the chief of Isser: "Thy name becomes like (that of) Qedjerdi, the chief of Isser, when the hyena found him in the balsam-tree."[8]

The composition of the satirical interchange between the scribes comes across as quite well written especially where Hori describes Amenemope as incompetent toward the end, giving as an example his poor management of not just his chariot but his character.

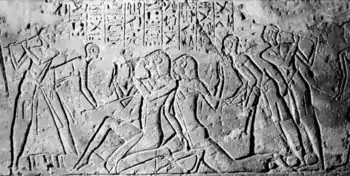

Amenemope traverses a mountain pass. Hori makes clear that these involve routes that should be well known to the scribes operating as mahers or messengers and scouts. Illustrations from the Battle of Kadesh provide an excellent background for Hori's tale showing the form of the chariots, and the size of the Shashu.

Hori sets this up as an incident in which the incompetence, inexperience and fear of Amenemope results in damage to his chariot. Amenemope's lack of experience causes him not to be apprehensive when he should be and then panicking when he should remain calm.

The(?) narrow defile is infested(?) with Shosu concealed beneath the bushes; some of them are of four cubits or of five cubits, from head(??) to foot(?), fierce of face, their heart is not mild, and they hearken not to coaxing. Thou art alone, there is no helper(?) with thee, no army behind thee. Thou findest no ///////// to make for thee a way of crossing. Thou decidest(?) (the matter) by marching onward, though thou knowest not the road. Shuddering(?) seizes thee, (the hair of) thy head stands up(?), thy soul is in thy hand. Thy path is filled with boulders and pebbles, without a passable track(??), overgrown with reeds and brambles, briers (?) and wolf's-pad. The ravine is on one side of thee, the mountain rises(?) on the other. On thou goest jolting(?), thy chariot on its side.

— Papyrus Anastasi I, p. XIX[8]

Hori piles on the results of Amenemope's inexperience and lack of expertise to show his state of mind clearly, including the part where he releases his pain and fear by forcing his way to the maiden who keeps watch over the gardens when he reaches Joppa:

Thou fearest to crush(?) thy horse. If it be thrown towards the abyss(?), thy collar-piece(?) is left bare(?), thy girth(?) falls. Thou unfastenest the horse so as to repair the collar-piece(?) at the top of the defile. Thou art not expert in the way of binding it together; thou knowest not how to tie(?) it. The ///////// is left where it is; the chariot is too heavy to bear the load of it(?). Thy heart is weary. Thou startest trotting(?). The sky is revealed. Thou fanciest that the enemy is behind thee; trembling seizes thee. Would that thou hadst a hedge of ///////// to put-upon the other side! The chariot is damaged(?) at the moment thou findest a camping-place(?). Thou perceivest the taste of pain! Thou hast entered Joppa, and findest the flowers blossoming in their season. Thou forcest a way in(?) ///////// Thou findest the fair maiden who keeps watch over the gardens. She takes thee to herself for a companion, and surrenders to thee her charms.

— Papyrus Anastasi I, p. XIX[9]

British Museum registration numbers

References

- Papyrus British Museum 10247

- Gardiner 1911, p. 1.

- Arnold, Dieter (2002). The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture. London: I.B.Tauris. p. 40. ISBN 1-86064-465-1.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (2000). Ramesside Inscriptions. Blackwell. p. 530.

- Gardiner 1911, p. 24.

- Gardiner 1911, p. 20, footnote 7.

- Gardiner 1911, p. 5.

- Gardiner 1911, p. 25.

- Gardiner 1911, p. 26–27.

Bibliography

- Brugsch, Heinrich Karl (1867). Examen critique du livre de m. Chabas, intitulé Voyage d'un Égyptien (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Chabas, François Joseph (1866). Voyage d'un Egyptien. Paris: J. Dejussieu.

- Fischer-Elfert, Hans-Werner (1983). Die satirische Streitschrift des Papyrus Anastasi I: Textzusammenstellung. Kleine Ägyptische Texte 1992a (in German).

- Fischer-Elfert, Hans-Werner (1986). Die satirische Streitschrift des Papyrus Anastasi I: Übersetzung und Kommentar (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-02612-X.

- Gardiner, Alan H. (1911). Egyptian Hieratic Texts - Series I: Literary Texts of the New Kingdom, Part I. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

- Leibovitch, J. (1938). "Quelques remarques au sujet du papyrus Anastasi I". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte (in French). Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. 38: 349–352.

External links

- Gardiner, Alan H. "Papyrus Anastasi I: A Satirical Letter". Archived from the original on 2011-02-01.