Clothing in ancient Greece

Clothing in ancient Greece refers to clothing starting from the Aegean bronze age (3000 BCE) to the Hellenistic period (31 BCE).[1] Clothing in ancient Greece included a wide variety of styles but primarily consisted of the chiton, peplos, himation, and chlamys.[2] Ancient Greek civilians typically wore two pieces of clothing draped about the body: an undergarment (χιτών : chitōn or πέπλος : péplos) and a cloak (ἱμάτιον : himátion or χλαμύς : chlamýs).[3] The people of ancient Greece had many factors (political, economic, social, and cultural) that determined what they wore and when they wore it.[2]

Clothes were quite simple, draped, loose-fitting and free-flowing.[4] Customarily, clothing was homemade and cut to various lengths of rectangular linen or wool fabric with minimal cutting or sewing, and secured with ornamental clasps or pins, and a belt, or girdle (ζώνη: zōnē).[5] Pieces were generally interchangeable between men and women.[6] However, women usually wore their robes to their ankles while men generally wore theirs to their knees depending on the occasion and circumstance.[7] Additionally, clothing often served many purposes than just being used as clothes such as bedding or a shroud.[8]

Textiles

Small fragments of textiles have been found from this period at archeological sites across Greece.[9] These found textiles, along with literary descriptions, artistic depictions, modern ethnography, and experimental archaeology, have led to a greater understanding of ancient Greek textiles.[10] Clothes in ancient Greece were mainly homemade or locally made.[11] All ancient Greek clothing was made out of natural fibers.[12] Linen was the most common fabric due to the hot climate which lasted most of the year.[13] On the rare occasion of colder weather, ancient Greeks wore wool.[14] Silk was also used for the production of clothing though for ceremonial purposes by the wealthy.[15] In Aristotle's The History of Animals, Aristotle talks about the collection of caterpillar cocoons to be used to create silk.[16]

_MET_gr31.11.10.AV1.jpg.webp)

_MET_gr31.11.10.R.jpg.webp)

Production Process

In the production of textiles, upright warp-weighted loom were used to weave clothing in Ancient Greece.[17]

These looms had vertical threads or warps that were held down by loom weights.[17] The use of looms can be seen in Homer's Odyssey when Hermes comes across Calypso weaving on a loom.[18] Another example of the loom in Homer's Odyssey can be seen when Odysseus comes across Circe for the first time.[19] The use of looms can also be seen being depicted on ancient Greek pottery.[20]

Color and Decoration

Clothing in ancient Greece has been found to be quite colorful with a wide variety of hues.Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.</ref> Colors found to be used include black, red, yellow, blue, green, and purple.[7] Yellow dyed clothing has been found to be associated with a woman's life cycle.[7] The elite typically wore purple as a sign of wealth and money as it was the most expensive dye due to the difficulty in acquiring it.[21] The ancient Greeks also embroidered designs into their clothes as a form of decoration.[22] The designs embroidered included representations of florals patterns and geometric patterns as well intricate scenes from Greek stories.[22] An example of this embroidery can be seen in Homer's Iliad where Helen is described as a purple textile where she embroidered a scene Trojans in battle.[23]

Styles of Clothing

The epiblema (ἐπίβλημα) was a general term for the outer clothing[24][25][26] also called ἀμφελόνη,[27] while the endyma (ἔνδυμα) was oftenest applied to the underclothing.[28]

Chiton

The chiton (plural: chitones) was a garment of light linen consisting of sleeves and long hemline.[2][8] It consisted of a wide, rectangular tube of material secured along the shoulders and lower arms by a series of fasteners.[29] The chiton was commonly worn by both men and women but the time period in which each did so depended.[30] Chitons typically fell to the ankles of the wearer, but shorter chitons were sometimes worn during vigorous activities by athletes, warriors, or slaves.[31]

Often excess fabric would be pulled over a girdle, or belt, which was fastened around the waist (see kolpos).[3] To deal with the bulk sometimes a strap, or anamaschalister was worn around the neck, brought under the armpits, crossed in the back, and tied in the front.[3] A himation, or cloak, could be worn over top of the chiton.[2]

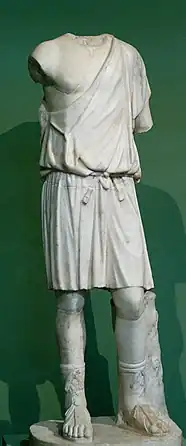

Chlamys

The chlamys was a seamless rectangle of woolen material worn by men for military or hunting purposes.[3] It was worn as a cloak and fastened at the right shoulder with a brooch or button.[32]

The chlamys was typical Greek military attire from the 5th to the 3rd century BC.[33] It is thought that the chlamys could ward against light attacks in war.[2]

The chlamys went on to become popular in the Byzantine Empire by the high class and wealthy.[34]

Himation

The himation was a simple wool outer garment worn over the peplos or chiton by both men and women.[2][8] It consisted of heavy rectangular material, passing under the left arm and secured at the right shoulder.[35] The himation could also be worn over both shoulders.[36] Woman can be seen wearing the himation over their head in depictions of marriages and funerals in art.[36] Man and boys can also be seen depicted in art as wearing solely the himation with no other clothing.[37] A more voluminous himation was worn in cold weather.[3] The himation is referenced as being worn by Socrates in Plato's Republic.[38]

Peplos

The peplos was a rectangular piece of woolen garment that was pinned at both shoulders leaving the cloth open down one side which fell down around the body.[2][8] The top third of the cloth was folded over to create an over-fold.[39] The use of a girdle or belt was be used to fasten the folds at the waist and could be worn over or under the over-fold.[40] Variations of the peplos were worn by women in many periods such as the archaic, early classical, and classical periods of ancient Greece.[41]

Allix

Allix (Ἄλλικα) and Gallix (Γάλλικά) was a chlamys according to Thessalians.[42]

Ampechone

Ampechone (ἀμπεχόνη, ἀμπέχονον, ἀμπεχόνιον), was a shawl or scarf worn by women over the chiton or inner garment.[43][44][45]

Βirrus

Βirrus or Βurrus (βίρρος), was a cloak or cape furnished with a hood; a heavy, coarse garment for use in bad weather.[46]

Chitoniskos

Chitoniskos (χιτωνίσκος), was a short chiton[47] sometimes worn over another chiton.[48]

Chlaina

Chlaina (Χλαῖνα) or Chlaine (Χλαῖνη), was a thick overgarment/coat. It was laid over the shoulders unfolded (ἁπλοΐς; haploís) or double-folded (δίπλαξ; díplax) with a pin.

Dalmatica

Dalmatica (Δαλματική) or Delmatica (Δελματική), a tunic with long sleeves, introduced from Dalmatia.[52]

Diphthera

Diphthera (Διφθέρα) (meaning leather), a shepherd's wrap made of hides.[53]

Exomis

The exomis was a tunic which left the right arm and shoulder bare. It was worn by slaves and the working classes.[54][55] In addition, it was worn by some units of light infantry.

Encomboma

The encomboma (ἐγκόμβωμα) was an upper garment tied round the body in a knot (κόμβος), whence the name, and worn to keep the tunic clean.[56][57]

Egkuklon and Tougkuklon

Egkuklon (Ἔγκυκλον) and Tougkuklon (Τοὔγκυκλον) were woman's upper garment.[58]

Katonake

Katonake (Κατωνάκη), it was a cloak which had a fleece (nakos) hanging from the lower (kato) parts, that is a wrapped-around hide and stretched down to the knees.[60]

Krokotos

Krokotos (Κροκωτός) was a saffron-coloured robe/chiton.

Phoinikis

Phoinikis (Φοινικὶς) was a military chlamys.[63]

Sisura

Sisura (Σισύρα or Σίσυρα) or Sisurna (Σίσυρνα),[64] type of inexpensive cloak/mantle, like a one-shoulder tunic.[65]

Spolas

Spolas (Σπολάς), a leather cloak, perhaps being worn on top.[66]

Tribon

Tribon (Τρίβων), simple cloak. It was worn by Spartan men and was the favorite garment of the Cynic philosophers.[68][69][70][71]

Undergarments

Women often wore a strophic, the bra of the time, under their garments and around the mid-portion of their body.[72] The strophic was a wide band of wool or linen wrapped across the breasts and tied between the shoulder blades.[3]

Men and women sometimes wore triangular loincloths, called perizoma, as underwear.[3]

Nudity

The ancient Greeks viewed nudity as an essential part of their identity that set them apart from other cultures.[73] Males went nude for athletic events such as the Olympics.[73] Male nudity could also be seen in Symposiums, a social event for elite men.[74] Male nudity could also be seen in rituals such as a boys coming of age ceremony.[74] Public female nudity was generally not accepted in ancient Greece,[73] though occasionally woman are nude in athletic events and religious rituals.[73] Women who were sex workers are commonly depicted as nude in ancient Greek art.[75] Partial nudity could also be seen through the linen fabric being expertly draped around the body, and the cloth could be slightly transparent.[76]

Accessories

Fasteners, Buttons, and Pins

_MET_DP244032.jpg.webp)

Since clothing was rarely cut or sewn, fasteners and buttons were often used to keep garments in place.[77][78] Small buttons, pins, and brooches were used.[79][80]

Porpe (πόρπη), was the pin of a buckle or clasp and also the clasp itself.[81] Large straight pins, called peronai were worn at the shoulders, facing down, to hold the chiton or peplos in place.[3] Fibulae were also used to pin the chiton, peplos or chlamys together.[82] These Fibulae were an early version of the safety pin.[82] In Sophocles' Oedipus Rex, Oedipus uses pins to stab his eyes out after learning he was the one to kill his father and marry his mother.[83]

Belts, sashes, or girdles were also worn at the waist to hold chitons and peplos.[2][84]

Zone (ζώνη) was a flat and rather broad girdle worn by young unmarried women (ζώνη παρθενική) around their hips. In addition, it was a broad belt worn by men round their loins, and made double or hollow like our shot-belts, for carrying money. Furthermore, it was also called a soldier's belt, worn round the loins, to cover the juncture of the cuirass and the kilt of leather straps.[85]

Footwear

Men and women wore footwear such as sandals, shoes or boots, which were made most commonly out of leather.[86][87] At home, people typically went barefoot.[88] It was also common for philosophers such as Socrates to be barefoot as well.[87]

The Athenian general, Iphicrates, made soldiers' boots that were easy to untie and light. These boots were called afterwards, from his name, Iphicratids (Greek: Ἰφικρατίδες).[89][90]

The bodyguards of the Peisistratid tyrants were called wolf-feet (Λυκόποδες). According to one theory, they were called like this because they had their feet covered with wolf-skins, to prevent frostbites.[91]

Kassyma (κάσσυμα) was an extra thick sole for the shoe or sandal frequently used to increase the height of the wearer. They were made of cork.[92]

Other Footwear

Arbele (ἀρβύλη, arbýlē), a short or half-boot.[93]

Baucides (βαυκίδες, baukídes) or Boucidium (βουκίδιον, boukídion), a kind of costly shoe of a saffron colour, worn exclusively by women.[94]

Carbatina (καρβατίνη, karbatínē), shoes worn by rustics, with sole and upper leather all in one. A piece of untanned ox-hide placed under the foot and tied up by several thongs, so as to cover the whole foot and part of the leg.[95]

Crepida (κρηπίς, krēpís), a kind of shoe between a closed boot and plain sandals.[96]

Croupezai (κρούπεζαι, kroúpezai), croupezia (κρουπέζια, kroupézia), or croupala (κρούπαλα, kroúpala), wooden shoes worn by peasants and took their names from noise which they made. Photius wrote that they were used for treading out olives.[97]

Embas (ἐμβάς, embás) or embates (ἐμβάτης, embátēs), kind of a closed boot.[98]

Endromis (ἐνδρομίς, endromís), a kind of a leather boot (In Roman times endromis was a thick woollen rug/cloak).[99][100]

Headgear

Women and men wore different types of headgear.[2] Women could wear veils to preserve their modesty.[101] Men would wear hats for protection against the elements.[102] Both men and women also wore different types of headbands to pull their hair up or for decoration.[101]

Pileus and petasos were common hats for men in ancient Greece.[103] The pilues was a close-fitting cap which could have been made out of a variety of materials such as leather and wool.[103] While the petasos was a broad brimmed hat with an attached cord that hung down around the chin.[103]

Kredemnon (κρήδεμνον) was a woman's headdress or veil of uncertain form, a sort of covering for the head with lappets hanging down to the shoulders on both sides, and when drawn together concealing the face.[104][105][106]

Ampyx (ἄμπυχ) was a headband worn by Greek women to confine the hair, passing round the front of the head and fastening behind. It appears generally to have consisted of a plate of gold or silver, often richly worked and adorned with precious stones.[107]

Sphendone (σφενδόνη) was a fastening for the hair used by the Greek women.[108]

Tainia was a headband, ribbon, or fillet.

Kekryphalos (κεκρύφαλος) was a Hairnet[109] and Sakkos (σάκκος) a hair sack/cap used by the Greek women.[109]

Diadema (διάδημα), a fillet which was the emblem of sovereignty.[110]

Jewelry

Ornamentation in the form of jewelry, elaborate hairstyles, and make-up was common for women.[111] While jewelry was used to decorates oneself, it was also used as status symbol to show one's wealth.[112] The Greeks wore jewelry such as rings, wreaths, diadems, bracelets, armbands, pins, pendants, necklaces, and earrings.[113] Small gold ornaments would be sewn onto their clothing and would glitter as they moved.[3] Common designs on jewelry in ancient Greece included plants, animals and figures from Greek mythology.[114] Gold and silver were the most common mediums for jewelry.[115] However, jewelry from this time could also have pearls, gems, and semiprecious stones used as decoration.[116] Jewelry was commonly passed down in families from generation to generation.[113]

References

- Condra, Jill (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through World History, Vol. 1. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33662-1.

- Nigro, Jeff (2022-02-01). "Ancient Greek Dress: The Classic Look". Art Institute of Chicago.

- Alden, Maureen (January 2003), "Ancient Greek Dress", Costume, 37 (1): 1–16, doi:10.1179/cos.2003.37.1.1

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Adkins, Lesley, and Roy Adkins. Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece. New York: Facts On File, 1997. Print.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- "Ancient Greek Dress". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-05-20.

- Johnson, Marie, Ethel B. Abrahams, and Maria M. L. Evans. Ancient Greek Dress. Chicago: Argonaut, 1964. Print.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Condra, Jill (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through World History, Vol. 1. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33662-1.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Aristotle. (1902). History of animals in ten books. London: G. Bell.

- Broudy, Eric (1993). The book of looms: a history of the handloom from ancient times to the present. Hanover: Brown University Press. ISBN 978-0-87451-649-4.

- Homer (2018-11-15), "Odyssey", Homer: Odyssey, Book 5, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-878880-5, retrieved 2023-06-04

- Homer (2018-11-15), "Odyssey", Homer: Odyssey, Book 10, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-878880-5, retrieved 2023-06-04

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Johnson, Marie, Ethel B. Abrahams, and Maria M. L. Evans. Ancient Greek Dress. Chicago: Argonaut, 1964. Print.

- Homer (1995-06-29), "Iliad", Homer: Iliad Book Three, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-814130-3, retrieved 2023-06-05

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Epiblēma

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Amictus

- Perseus Encyclopedia, epiblema

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, ἀμφελόνη

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Indūtus

- Garland, Robert. Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2009. Print.

- Condra, Jill (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through World History, Vol. 1. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33662-1.

- Johnson, Marie, Ethel B. Abrahams, and Maria M. L. Evans. Ancient Greek Dress. Chicago: Argonaut, 1964. Print.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Ancient Greek Dress Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–2013. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Condra, Jill (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through World History, Vol. 1. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33662-1.

- Johnson, Marie, Ethel B. Abrahams, and Maria M. L. Evans. Ancient Greek Dress. Chicago: Argonaut, 1964. Print.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Condra, Jill (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through World History, Vol. 1. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33662-1.

- Plato (September 14, 2007). The Republic. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-045511-3.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Condra, Jill (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through World History, Vol. 1. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33662-1.

- Suda, alpha, 1224

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890)William Smith, LLD, William Wayte, G. E. Marindin, Ed., Ampechone

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon, Ampechone

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Ampechone

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Birrus

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon, Chitoniskos

- Perseus Encyclopedia, Chitoniskos

- John Conington, Commentary on Vergil's Aeneid, Volume 2, 9.616

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Manica

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon, Chiridotos

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Dalmatica

- Suda, delta, 1290

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), William Smith, LLD, William Wayte, G. E. Marindin, Ed., Comoedia

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Exōmis

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), William Smith, LLD, William Wayte, G. E. Marindin, Ed., Encomboma

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Encombōma

- Suda, tau, 812

- "L. D. Caskey, J. D. Beazley, Attic Vase Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 110. 00.346 BELL-KRATER from Vico Equense (NE. of Sorrento) PLATE LXII". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- Suda, kappa, 1114

- Francesca Sterlacci; Joanne Arbuckle (2009). The A to Z of the Fashion Industry. Scarecrow Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8108-6883-0.

- Herbert Norris (1999). Ancient European Costume and Fashion. Dover Publications. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-486-40723-4.

- Suda, phi, 791

- Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, sisura

- Suda, sigma, 487

- Suda, Sigma, 956

- Suda, tau, 465

- Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, Tribon

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), William Smith, LLD, William Wayte, G. E. Marindin, Ed., Pallium

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Tribon

- Mireille M. Lee (2015). Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-107-66253-7.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Bonfante, Larissa (1989-10-01). "Nudity as a Costume in Classical Art". American Journal of Archaeology. 93 (4): 543–570. doi:10.2307/505328. ISSN 0002-9114.

- Bonfante, Larissa (1990). "The NAKED GREEK". Archaeology. 43 (5): 28–35. ISSN 0003-8113.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Johnson, Marie, Ethel B. Abrahams, and Maria M. L. Evans. Ancient Greek Dress. Chicago: Argonaut, 1964. Print.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Johnson, Marie, Ethel B. Abrahams, and Maria M. L. Evans. Ancient Greek Dress. Chicago: Argonaut, 1964. Print.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Johnson, Marie, Ethel B. Abrahams, and Maria M. L. Evans. Ancient Greek Dress. Chicago: Argonaut, 1964. Print.

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Porpé

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Sophocle; Mulroy, David D. (2011). Oedipus Rex. Wisconsin studies in classics. Madison (Wis.): University of Wisconsin press. ISBN 978-0-299-28254-7.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Zona

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Johnson, Marie, Ethel B. Abrahams, and Maria M. L. Evans. Ancient Greek Dress. Chicago: Argonaut, 1964. Print.

- Ancient Greek Dress Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–2013. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Schachter, Albert (May 2016). Boiotia in Antiquity: Selected Papers. Cambridge University Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-107-05324-3.

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890) William Smith, LLD, William Wayte, G. E. Marindin, Ed., calceus

- Suda, lambda, 812

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Fulmenta

- Suda, alpha, 3755

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Baucides

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Carbatina

- Dictionary A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Crepida

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Sculponeae

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Embas

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Endromis

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Endromis

- Johnson, Marie, Ethel B. Abrahams, and Maria M. L. Evans. Ancient Greek Dress. Chicago: Argonaut, 1964. Print.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Calantica

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon, krhdemnon

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Calautica

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Ampyx

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Sphendone

- The Prostitute and Her Headdress: the Mitra, Sakkos and Kekryphalos in Attic Red-figure Vase-painting ca. 550-450 BCE, Marina Fischer

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Diadema

- Johnson, Marie, Ethel B. Abrahams, and Maria M. L. Evans. Ancient Greek Dress. Chicago: Argonaut, 1964. Print.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Colette Hemingway; Seán Hemingway. "Hellenistic Jewelry". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

- Smith, Tyler Jo; Plantzos, Dimitris, eds. (2013-01-29). A Companion to Greek Art. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118273289.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2015). Body, dress, and identity in ancient Greece. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05536-0.

External links

- Ancient Greek Clothing

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Clothing

Garment

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Abolla

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Ephestris

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Epiblema

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Amictus

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Pallium

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Palla

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Paludamentum

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Cingulum

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Mitra

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Dalmatica

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Tunica

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Laena

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Lacerna

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Cucullus

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Cyclas

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Paenula

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Paludamentum

Footwear

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Calceus

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Calceus

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Carbatina

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Crepida

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Crepida

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Cothurnus

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Caliga

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Baucides

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Baucides

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Baxeae

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Baxeae

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Embas

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Embas

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Endromis

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Soccus

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Solea

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Talaria

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Zancha

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Fulmenta

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Gallicae

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Ligula

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Obstragulum

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Phaecasium

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Sandalium

Other

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Strophium

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Ampyx

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Calautica

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Armilla

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Inauris

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Inauris

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Manica

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Nodus

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Bulla

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Amuletum

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Fibula

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Fibula

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Porpé

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Caliendrum

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Redimiculum

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Baculum

- The Prostitute and Her Headdress: the Mitra, Sakkos and Kekryphalos in Attic Red-figure Vase-painting ca. 550-450 BCE, Marina Fischer

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Zona

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Taenia

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Catena