Tondo (historical polity)

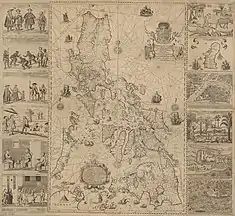

In early Philippine history, the Tagalog settlement at Tondo (Tagalog: [tunˈdo]; Baybayin: ) sometimes referred to as the Kingdom of Tondo, was a major trade hub located on the northern part of the Pasig River delta, on Luzon island. Together with Maynila, the polity (bayan) that was also situated on the southern part of the Pasig River delta, had established a shared monopoly on the trade of Chinese goods throughout the rest of the Philippine archipelago, making it an established force in trade throughout Southeast Asia and East Asia.[15][7][16][9][17][19]

Tondo Tundun[1] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before 900[2][Notes 1]–1589[3] | |||||||||||

Tondo, Pasig, and other barangays under the influence of Dayang Kalangitan of Pasig in c.1450. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Tondo | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Tagalog, Kapampangan, and Classical Malay[2] | ||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||

| Government | Bayan feudal monarchy ruled by a king with the title lakan, consisting of several barangay duchies that are ruled by the respective datu[9][5][10][11] | ||||||||||

| Lakan | |||||||||||

• c. 900 | Unnamed ruler represented by Jayadewa, Lord Minister of Pailah (according to a record of debt acquittance) | ||||||||||

• 1450–1500 | Rajah Lontok and Dayang Kalangitan | ||||||||||

• 1521–1571 | Lakandula | ||||||||||

• 1571–1575 | Rajah Sulayman | ||||||||||

• 1575–1589 | Agustin de Legazpi | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity to Early modern[2][Notes 3] | ||||||||||

• First historical mention, in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription; trade relations with the Mataram Kingdom implied[2] | before 900[2][Notes 4] | ||||||||||

• Various proposed dates for the founding of the neighboring Rajahnate of Maynila range as early as the 1200s (see Battle of Manila (1258) and (1365)) to the 1500s (see Battle of Manila (1500))[Notes 5] | c. 1200s to c. 1500s | ||||||||||

| 1373 | |||||||||||

| c. 1520 | |||||||||||

| 1570 | |||||||||||

| 1571 | |||||||||||

• Attack of Limahong and concurrent Tagalog revolt of 1574 | 1574 | ||||||||||

• Discovery of the Tondo Conspiracy, dissolution of indigenous rule, and integration into the Spanish East Indies | 1589[3] | ||||||||||

| Currency | Piloncitos, Gold rings, and Barter[14] | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Philippines | ||||||||||

| History of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Tondo is of particular interest to Filipino historians and historiographers because it is one of the oldest historically documented settlements in the Philippines. Scholars generally agree that it was mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, the Philippines' oldest extant locally produced written document, dating back to 900 A.D.[2][9][20]

Following contact with the Spanish beginning in 1570 and the defeat of local rulers in the Manila Bay area in 1571, Tondo was ruled from Intramuros, a Spanish fort built on the remains of the Maynila polity. Tondo's absorption into the Spanish Empire effectively ended its status as an independent political entity; it now exists as a district of the modern City of Manila.

History

Geographically, the settlement was completely surrounded by bodies of water: mainly the Pasig River to the south and the shore of Manila Bay to the west, but also by several of the delta's rivulets: the Canal de la Reina to the southeast, the Estero de Sunog Apog to the northeast, and the Estero de Vitas on its eastern and northernmost boundaries.[21]

It is referred to in academic circles as the "Tondo polity" or "Tondo settlement",[7][9][5] and the earliest Tagalog dictionaries categorized it as a "bayan" (a "city-state",[22] "country" or "polity", lit. '"settlement"').[9][5]

Early travellers from monarchical cultures who had contacts with Tondo (including the Chinese, Portuguese and the Spanish)[20] often initially referred to it as the "Kingdom of Tondo". Early Augustinian chronicler Pedro de San Buenaventura explained this to be an error as early as 1613 in his Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, but historian Vicente L. Rafael notes that the label was nevertheless later adapted by the popular literature of the Spanish colonial era because Spanish language writers of the time did not have the appropriate words for describing the complex power relations on which Maritime Southeast Asian leadership structures were built.[10] The earliest firsthand Spanish accounts described it as a smaller "village", in comparison to the fortified polity of Maynila.[23]

Politically, Tondo was made up of several social groupings, traditionally[24] referred to by historians as barangays,[5][7][25] which were led by datus.[9][5][25] These datus in turn recognised the leadership of the most senior among them as a sort of "paramount datu" called a lakan over the bayan.[9][5][7] In the middle to late 16th century, its lakan was held in high regard within the alliance group which was formed by the various Manila Bay area polities, which included Tondo, Maynila, and various polities in Bulacan and Pampanga.[5][25] Extrapolating from available data, the demographer-historian Linda A. Newson has estimated that Tondo may have had a population of roughly 43,000 when the Spanish first arrived in 1570.[26]

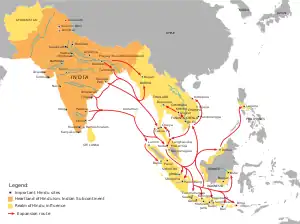

Culturally, the Tagalog people of Tondo had a rich Austronesian (specifically Malayo-Polynesian) culture, with its own expressions of language and writing, religion, art, and music dating back to the earliest peoples of the archipelago.[27][6] This culture was later influenced by its trading relations with the rest of Maritime Southeast Asia.[6][28] Particularly significant were its relations with Ming dynasty,[29] Malaysia, Brunei, and the Majapahit empire, which served as the main conduit for significant Indian cultural influence, despite the Philippine archipelago's geographical location outside the Indian cultural zone.[6][7][30][28]

Sources and historiography

Only a few comprehensive reviews of source materials for the study of Philippine prehistory and early history have been done, with William Henry Scott's 1968 review being one of the earliest systematic critiques.[31] Scott's review has become a seminal academic work on the study of early Philippine history, having been reviewed early on by a panel of that era's most eminent historians and folklorists including Teodoro Agoncillo, Horacio de la Costa, Marcelino Foronda, Mercedes Grau Santamaria, Nicholas Zafra and Gregorio Zaide.[32] Scott's 1968 review was acknowledged by Laura Lee Junker when she conducted her own comprehensive 1998 review of primary sources regarding archaic Philippine polities,[31] and by F. Landa Jocano in his anthropological analysis of Philippine prehistory.[7]

Scott lists the sources for the study of Philippine prehistory as: archaeology, linguistics and paleogeography, foreign written documents, and quasi-historical genealogical documents. In a later work,[5] he conducts a detailed critique of early written documents and surviving oral or folk traditions connected with the Philippines early historic or protohistoric era.[7]

Sources Scott,[20][5] Jocano,[7] and Junker[31] consider particularly relevant to the study of the Tondo and Maynila settlements include:

- Malay texts,[31][20][5]

- Philippine oral traditions,[31][7]

- Chinese tributary records and geographies,[31][20][5]

- early Spanish writings,[31][5] and

- archeological evidence from the region around Manila Bay, the Pasig River, and Laguna Lake.[31][20][5][7]

Primary sources for the history of Rajah Kalamayin's Namayan, further upriver, include artifacts dug up from archaeological digs (the earliest of which was Robert Fox's[33] work for the National Museum in 1977) and Spanish colonial records (most notably those compiled by the 19th-century Franciscan historian Fray Felix Huerta).[34]

A more detailed discussion of notable archaeological, documentary, and genealogical sources can be found towards the end of this article.

Critical historiography

Junker notes that most of the primary written sources for early Philippine history have inherent biases, which creates a need to counter-check their narratives with one another, and with empirical archaeological evidence.[31] She cites the works of F. Landa Jocano, Felix M. Keesing, and William Henry Scott as notable exceptions.[31]

F. Landa Jocano warns that in the case of early Philippine history, it's essential that "even archaeological findings" be carefully interpreted by experts, because these can be misinterpreted if not analyzed in proper context.

Names and etymology

Alternative names and orthographies

As a result of Tondo's history as a center of commerce, it has been referred to by many names by in various texts and languages. It is variously also referred to as Tundo, Tundun, Tundok, Tung-lio, Tundaan, Tunduh, Tunda, or Tong-Lao.[35]

Origins of the name "Tondo"

Numerous theories on the origin of the name "Tondo" have been put forward. Filipino National Artist Nick Joaquin suggested that it might be a reference to high ground ("tundok").[36] The French linguist Jean-Paul Potet, however, has suggested that the river mangrove, Aegiceras corniculatum, which at the time was called "tundok" ("tinduk-tindukan" today), is the most likely origin of the name.[37]

Tondo as a "Bayan"

According to the earliest Tagalog dictionaries,[9][5] large coastal settlements like Tondo and Maynila, which were ultimately led by a lakan or rajah, were called "bayan" in the Tagalog language.[9][5][25] This term (which is translated today as "country" or "town") was common among the various languages of the Philippine archipelago,[38] and eventually came to refer to the entire Philippines, alongside the word bansa (or bangsa, meaning "nation").

However, the precolonial settlement of Tondo has also been described using a number of descriptors.

The earliest firsthand Spanish accounts described it as a smaller "village", in comparison to the fortified polity of Maynila.[23] However, this term is no longer used in academic circles because it reflects the strong hispanocentric bias of the Spanish colonizers.[20]

Travellers from monarchical cultures who had contacts with Tondo (including the Chinese, Portuguese and the Spanish)[20] also often initially mislabelled[20][5][9] it as the "Kingdom of Tondo". Early Augustinian chronicler Pedro de San Buenaventura explained this to be an error as early as 1613 in his Vocabulario de la lengua tagala. Historian Vicente L. Rafael notes, however, that the label was later adapted by the popular literature of the Spanish colonial era anyway, because Spanish-language writers of the time did not have the appropriate words for describing the complex power relations on which Maritime Southeast-Asian leadership structures were built.[10]

Historian F. Landa Jocano has described Tondo using the term "large barangay", making Tondo out to be a larger version of what Filipino historians have traditionally considered the "basic political structure" of pre-colonial societies.[7] However, the use of the term "barangay" for such purposes has recently been brought to question by historian Damon Woods, who believes that the use of this term was the result of a 20th-century American mistranslation of the writings of Juan de Plasencia.[24]

In an effort to avoid cross-cultural inaccuracies regarding the political structure of Tondo,[20] it is usually described in academic texts using generic umbrella terms, where it is described as the "Tondo polity" or "Tondo settlement".[7][9][5]

Geographical location political influence

Scholars generally agree[9] that Tondo was located north of the Pasig river,[38] on the northern part of Lusong or Lusung, which is an Old Tagalog name for the Pasig river delta.[5]: 190–191 This name is thought to have been derived from the Tagalog word for a large wooden mortar used in dehusking rice.[39][40] This name eventually came to be used as the name for the entire island of modern Luzon.[41]

Territorial boundaries

Except in the case of fortified polities such as Maynila and Cainta, the first-hand descriptions of territorial boundaries of Tagalog polities tend to discourage scholars from providing exact delineations, because the descriptions depict the boundaries of even compact polities like Tondo as slowly diminishing concentrations of households, dissipating into agricultural land (parang) and eventually wild vegetation (sukal).[38]

However, Tondo's territorial boundaries are generally accepted as defined by several bodies of water which gave Tondo an island shape:[36][21]

- the Pasig River to the South;

- the Canal de la Reina, forming the Isla de Binondo between itself and Estero de Binondo[21] to the southeast,

- an eastern stretch of the Estero de Vitas[21] to the east,

- the Estero de Sunog Apog[21] to the northeast forming the Isla de Balut between itself and the Estero de Vitas,

- a northern stretch of the Estero de Vitas merging from the mouth of the Navotas River[21] to the north, and

- the original (pre-reclamation) shoreline of Manila Bay[21] to the west.

Notably, the area of modern Tondo now known as "Gagalangin" is not believed to have been part of Tondo's original "territory", since it was a place grown wild with plants in olden days.[21]

The shoreline of the modern district of Tondo has been significantly altered by reclamation activities. Pre-reclamation maps of Tondo show a relatively straight shoreline from the beachfront of Intramuros to the mouth of the Estero de Vitas.[42]

Tondo's territorial boundaries also excluded[5]: 191 [34] territory occupied by Maynila[5][43] Namayan (modern day Santa Ana),[33][34] Tambobong (modern day Navotas), Omaghicon (modern day Malabon), Pandacan, and Pasay – all of which had their own respective leaders.[21]

Notable areas

One notable area controlled by Tondo under the reign of Bunao Lakandula in the 1500s[5] was called "Baybay", now known as the district of San Nicolas, Manila.[44][21] William Henry Scott, citing Augustinian missionary records,[45] notes that Bunao Lakandula had allowed a group of Chinese refugees, fleeing persecution from Japan, to settle there. These refugees, which included two Christians, then "diked, drained, and reclaimed land along the waterfront", extending the shore of Tondo further out to Manila Bay.[5]

Another notable area controlled by Tondo was on the banks of the Estero de Vitas, called "Sunog Apog", which eventually lent its name to the nearby Estero de Sunog Apog in Gagalangin. This area was noted for the production of lime (apog) through the burning (pag-sunog) of oyster (talaba) shells, and a lime kiln was still present in the area by 1929.[46][21]

Polities influenced through the lakan's "alliance network"

Although popular portrayals and early nationalist historical texts sometimes depict Philippine paramount rulers, such as those in the Maynila and Tondo polities, as having broad sovereign powers and holding vast territories, critical historiographers such as Jocano,[7]: 160–161 Scott,[5] and Junker[25] explain that historical sources clearly show that paramount leaders, such as the lakans of Tondo and the rajahs of Maynila, exercised only a limited degree of influence, which did not include claims over the barangays[Notes 6] and territories of less-senior datus.

Junker describes this structure as an "alliance group", which she describes as having "a relatively decentralized and highly segmentary structure"[25]: 172 similar to other polities in Maritime Southeast Asia:[25]: 172

"In the Philippines, the primary unit of collective political action appears to have been an organizationally more fluid "alliance group," [...] made up of perpetually shifting leader-focused factions, represented the extension of [...] power over individuals and groups through various alliance-building strategies, but not over geographically distinct districts or territories."[25]: 172

The Malacañang Presidential Museum, on the other hand, described this political setup in their 2015 Araw ng Maynila briefers as an "alliance network."[9]

This explains the confusion experienced by Martin de Goiti during the first Spanish forays into Bulacan and Pampanga in late 1571.[23] Until that point, Spanish chroniclers continued to use the terms "king" and "kingdom" to describe the polities of Tondo and Maynila, but Goiti was surprised when Lakandula explained there was "no single king over these lands",[23][5] and that the leadership of Tondo and Maynila over the Kapampangan polities did not include either territorial claim or absolute command.[5] San Buenaventura (1613, as cited by Junker, 1990 and Scott, 1994) later noted that Tagalogs only applied the term Hari (King) to foreign monarchs, rather than their own leaders.[5]

Polities in Bulacan and Pampanga

The influence of Tondo and Maynila over the datus of various polities in pre-colonial Bulacan and Pampanga are acknowledged by historical records, and are supported by oral literature and traditions. This influence was assumed by Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, leading him to implore Bunao, the Lakan of Tondo, to join Martin de Goiti on his journey to Bulacan and Pampanga in late 1571. However, since the Lakandula did not have territorial sovereignty over these territories,[23][5] the effort met with limited success.[5]

Patanne, as well as Abinales and Amoroso, interpret Postma's translation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription as meaning that this influence-via-alliance-network defined Tondo's relationship with the territories of Binwangan, Pailah, and Puliran, which Postma believed to be in Bulacan/Pampanga.

Polities in Bulacan and Pampanga which were supposedly under the influence of Tondo and Maynila's alliance network include, but are not limited to:

- Paila, in Barangay San Lorenzo, Norzagaray, Bulacan (coordinates 14–54.5 & 121–06.9) – the "Pailah" mentioned in the LCI.[2]

- Pulilan, Bulacan (coordinates: 14–54.2 & 120–50.8) – the "Puliran" mentioned in the LCI.[2]

- Barangay Binwangan[47] in Obando[48] (coordinates: 14–43.2 & 120–543) – the "Binwangan" mentioned in the LCI.[2] It was also mentioned in the Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Islas Filipinas (1734) as Vinuanga.

- Candaba, Pampanga[49]

- Katanghalan, now the municipality of Obando, Bulacan[49]

- some other parts of Bulacan[49]

Laguna Lake region polities

Scholars, particularly Junker (1990) and Scott (1994) also acknowledge that Tondo and Maynila had a close relationship with "Puliran", the endonymously identified region covering the south-eastern shore of Laguna Lake. However, neither Junker nor Scott, or even other scholars such as Jocano, Odal-Devora, or Dery, do not explicitly characterize this relationship as Puliran being a part of Tondo and Maynila's alliance network.

The interpretation of Puliran as part of Tondo and Maynila's alliance network is instead implied by the challenge posed by the Pila Historical Society Foundation and local historian Jaime F. Tiongson to Postma's assertions regarding the exact locations of places mentioned in the Laguna copperplate.[50][51]

According to Tiongson's interpretation: Pailah refers to Pila; Puliran refers to Puliran, the old name of the territory that occupied the southeastern part of Laguna de Bay at the time; and Binwangan refers to modern-day Barangay Binawangan in Capalonga, Camarines Norte.[50][51]

Polities in the Puliran region which were supposedly under the influence of Tondo and Maynila's alliance network include, but are not limited to:

- The South-Eastern shore region of Laguna Lake – interpreted as the "Puliran Kasumuran" mentioned in the LCI[50][51]

- Pila, Laguna – interpreted as the "Pailah" mentioned in the LCI[2][50][51][52]

- Pakil, Laguna[53]

Culture and society

Since at least the 3rd century, the Tagalog people of Tondo had developed a culture which is predominantly Hindu and Buddhist society. They are ruled by a lakan, which belongs to a caste of Maharlika, were the feudal warrior class in ancient Tagalog society in Luzon, translated in Spanish as hidalgos, and meaning freeman, libres or freedman.[15] They belonged to the lower nobility class similar to the timawa of the Visayans. In modern Filipino, however, the term itself has erroneously come to mean "royal nobility", which was actually restricted to the hereditary maginoo class.[54]

| Tondo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 東都 / 呂宋 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kyūjitai | 呂宋 | ||||||

| |||||||

Social structure

The pre-colonial Tagalog barangays of Manila, Pampanga and Laguna had a more complex social structure than the cultures of the Visayas, enjoying a more extensive commerce through their Bornean political contacts, and engaging in farming wet rice for a living. The Tagalogs were thus described by the Spanish Augustinian friar Martin de Rada as more traders than warriors.[55]: "124–125"

In his seminal 1994 work Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society (further simplified in the briefer by the Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office in 2015), historian William Henry Scott delineates the three classes of Tagalog society during the 1500s:[9]

The term datu or lakan, or apo refers to the chief, but the noble class to which the datu belonged to was known as the maginoo class. Any male member of the maginoo class can become a datu by personal achievement.[55]: "125"

The term timawa referring to freemen came into use in the social structure of the Tagalogs within just twenty years after the coming of the Spaniards. The term, however, was being incorrectly applied to former alipin (commoner and slave class) who have escaped bondage by payment, favor, or flight. Moreover, the Tagalog timawa did not have the military prominence of the Visayan timawa. The equivalent warrior class in the Tagalog society was present only in Laguna, and they were known as the maharlika class.

At the bottom of the social hierarchy are the members of the alipin class. There are two main subclasses of the alipin class. The aliping namamahay who owned their own houses and served their masters by paying tribute or working on their fields were the commoners and serfs, while the aliping sa gigilid who lived in their masters' houses were the servants and slaves.

The more complex social structure of the Tagalogs was less stable during the arrival of the Spaniards because it was still in a process of differentiating.[55]: "124–125"

Leadership structure

Tondo was a large coastal settlement led by several leaders, called datu, who had their own followings, called either "dulohan" or "barangay".[5][9] These datus with their respective barangays in turn acknowledged the leadership of a datu with the most senior rank – a "paramount ruler"[31] or "paramount datu",[7] who was called a "lakan".[5][9] According to San Buenaventura, a large coastal settlement with this kind of leadership structure was called a "bayan".[5][9]

The equivalent paramount datus who led the southern polity of Maynila were referred to using the term "rajah", and in Mindanao, a similar title in more Islamized polities was that of "sultan".[7]

The term for the barangay social groupings refers to the large ships called balangay, which were common on such coastal polities, and is used by present-day scholars to describe the leadership structure of settlements in early Philippine history. This leads to some confusion for modern readers, because the term "barangay" was also later adapted (through the 1991 Local Government Code) as a replacement for the Spanish term barrio to describe the smallest administrative division in the modern Republic of the Philippines – a government structure very different from the original meaning of the word.[25][7][5]

In addition, Jocano warns that there were significant differences between "smaller" barangays, which were only 30 to 100 households in size, and considerably larger barangays, which according to Buenaventura were called "bayan". Jocano asserted that the social and governance structures of these larger barangays, with high levels of economic specialization and a clear system of social stratification, should be the primary model for the analysis of social structures in early Philippine history, rather than the "smaller" barangays.[7]

Popular literature has described these political entities as either chiefdoms or kingdoms.[9][36] Although modern scholars such as Renfew note that these are not appropriate technical descriptions.[17][9]

Contemporary historiographers specializing in early Philippine history prefer to use the generic term "polity" in international journals,[17][9] avoiding the terms "chiefdom" and "kingdom" altogether.

Scholars such as William Henry Scott and F. Landa Jocano have continued to use the term "barangay", especially in longer-form texts such as books and anthologies,[5][56] because these longer forms allow space for explanations of the differences between the modern and archaic uses of the word "barangay".

Cultural influences

Scholarly analysis of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, which includes the first historical mention of Tondo, suggests that Tondo was "culturally influenced" by the Hindu and Buddhist cultures of Maritime Southeast Asia as early as the 9th century.[57] The writing system used on the copperplate is the Old Kawi, while the language used is a variety of Old Malay, with numerous loanwords from Sanskrit and a few non-Malay vocabulary elements whose origin may be Old Javanese.[2] Some contend it is between Old Tagalog and Old Javanese. The date indicated on the LCI text says that it was etched in the year 822 of the Saka Era, the month of Waisaka, and the fourth day of the waning moon, which corresponds to Monday, April 21, 900 AD in the Proleptic Gregorian calendar.[58][59]

While these Hindu-Buddhist cultural influences can ultimately be traced to the cultures of the Indian subcontinent, scholars generally do not believe that it indicates physical contact between the Philippines and India.[6][7][5][2][28] The scope, sequence, and mechanism of Indian cultural influences in early Philippine polities continues to be an active area of research[2] and are the subject of much debate among scholars of Philippine and Southeast Asian history and historiography.[6][7][5][28]

During the reign of Sultan Bolkiah in 1485 to 1521, the Sultanate of Brunei decided to break Tondo's monopoly in the China trade by attacking Tondo and establishing the state of Selurung as a Bruneian satellite-state.[60][61]

Religion

Historical accounts,[4][5] supported by archeological and linguistic evidence[4][38][5] and by corroborated by anthropological studies,[4][5] show that the Tagalog people, including those in Tondo and Maynila, practiced a set of Austronesian beliefs and practices which date back to the arrival of Austronesian peoples,[62][27][5] although various elements were later syncretistically adapted from Hinduism, Mahayana Buddhism, and Islam.[6][5]

The Tagalogs did not have a specific name for this set of religious beliefs and practices, although later scholars and popular writers refer to it as Anitism,[62] or, less accurately, using the general term "animism."[4]

Tagalog religious cosmology

The Tagalog belief system was more or less anchored on the idea that the world is inhabited by spirits and supernatural entities, both good and bad, and that respect must be accorded to them through worship.[63]

According to the early Spanish missionary-ethnographers, the Tagalog people believed in a creator-god named Bathala,[4] whom they referred to both as maylicha (creator; lit. "actor of creation") and maycapal (lord, or almighty; lit. "actor of power").[5] Loarca and Chirino also report that in some places, they were called "Molayri" (Molaiari) or "Diwata" (Dioata)." However, these early missionary-ethnographers also noted that the Tagalogs did not include Bathala in their daily acts of worship (pag-a-anito). Buenaventura was informed that this was because the Tagalogs believed Bathala was too mighty and distant to be bothered with the concerns of mortal man, and so the Tagalogs focused their acts of appeasement to "lesser" deities and powers,[4] immediate spirits which they believed had control over their day-to-day life.[8]

Because the Tagalogs did not have a collective word to describe all these spirits together, Spanish missionaries eventually decided to call them "anito," since they were the subject of the Tagalog's act of pag-aanito (worship).[5] According to Scott, accounts and early dictionaries describe them as intermediaries ("Bathala's agents"), and the dictionaries used the word abogado (advocate) when defining their realms. These sources also show, however, that in practice, they were addressed directly: "in actual prayers, they were petitioned directly, not as intermediaries." Modern day writers divide these spirits are broadly into the categories of "Ancestor spirits, nature spirits, and guardian spirits," although they also note that the dividing line between these categories is often blurred.[4]

Demetrio, Cordero-Fernando, and Nakpil Zialcita[4] observe that the Luzon Tagalogs and Kapampangans' use of the word "Anito", instead of the word "Diwata" which was more predominant in the Visayan regions, indicated that these peoples of Luzon were less influenced by the Hindu and Buddhist beliefs of the Majapahit empire than the Visayans were.[4] They also observed that the words were used alternately amongst the peoples in the southernmost portions of Luzon – the Bicol Region, Marinduque, Mindoro, etc. They suggested that this have represented transitional area, the front lines of an increased "Indianized" Majapahit influence which was making its way north[4] the same way Islam was making its way north from Mindanao.[5]

Localization of other beliefs

Although most contemporary historians,[7][5] approaching Philippines from the point of view of critical historiography, assert the predominance of indigenous religious beliefs,[7][5] they also note that there are significant manifestations of other belief systems in early Tagalog history.[7] While it was common among mid-20th century historians and in earlier texts to use these manifestations as evidence of "influence,"[7] more contemporary scholars of southeast Asian history have emphasized that the manifestations of these beliefs do not necessarily reflect outright adoption of these religions, but rather of syncretistic adaptation[6] or "localization."[64][65]

Osborne (2004) describes a process of "adaptation" happening in connection with Hindu and Buddhist influences in the various cultures of Maritime Southeast Asia,[6] and emphasizes that this "indianization" of Southeast Asia did not per-se overwrite existing indigenous patterns, cultures, and beliefs:

"Because Indian culture "came" to Southeast Asia, one must not think that Southeast Asians lacked a culture of their own. Indeed, the generally accepted view is that Indian culture made such an impact on Southeast Asia because it fitted easily with the existing cultural patterns and religious beliefs of populations that had already moved a considerable distance along the path of civilization.[…] Southeast Asians, to summarize the point, borrowed but they also adapted. In some very important cases, they did not need to borrow at all.[6]: 24 "

Milner (2011)[64] suggests that this pattern of adaptation reflects what Wolters (1999) calls "localization," a process by which foreign ideas ("specifically Indian materials"[64]) could be "fractured and restated and therefore drained of their original significance" in the process of being adopted into "various local complexes."[65]

Hindu and Buddhist religious influences

It is not clear exactly how much the various cultures of the Philippine archipelago were influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism before the arrival of European colonizers. The current scholarly consensus is that although the Philippines was not directly influenced by India, Hindu and Buddhist cultural and religious influences reached the Philippines through trade – possibly on a small scale with the SriVijayan empire, and more definitively and extensively with the Majapahit empire.[7]

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription, which is the artifact which specifically points to an Indian cultural (linguistic) influence in Tondo, does not explicitly discuss religious practices.[47][59][2] However, some contemporary Buddhist practitioners believe that its mention of the Hindu calendar month of Vaisakha (which corresponds to April/May in the Gregorian Calendar) implies a familiarity with the Hindu sacred days celebrated during that month.[66]

Elsewhere in the Philippines, Hindu and Buddhist religious influences are evidenced by the presence of explicitly religious artifacts[67][68][69] – in at least one case as near to Tondo as Calatagan, Batangas.[70]

Contemporary Buddhist practitioners believe that Filipino cultures would have been exposed to the Vajrayana and Theravada schools of Buddhism through their trade contacts with the SriVijaya and Majapahit,[66] and archeological findings on the Island of Luzon have produced artifacts associated with the Mahayana school of Buddhism.[70]

Islamization

One clearer exception to the predominance of "Anitism" in early Tondo and Maynila was that the apex-level leaders of these polities identified themselves as Muslims,[5] as did the migrant sailor Luzones who were encountered by early 15th century chroniclers in Portuguese Malacca.[6] However, the various ethnographic reports of the period indicate that this seemed to only be a nominal identification ("Muslim by name") because there was only a surface level acknowledgement of Muslim norms (avoidance of pork, non-consumption of blood, etc.) without an "understanding of Mohammedan teachings."[23] Scholars generally believe that this nominal practice of Islam actually represented the early stages of Islamization, which would have seen a much more extensive practice of Muslim beliefs[5] had the Spanish not arrived and introduced their brand of Iberian Catholicism.[8][5]

Islamization was a slow process characterised by with the steady conversion of the citizenry of Tondo and Manila which created Muslim domains. The Bruneians installed the Muslim rajahs, Rajah Salalila and Rajah Matanda in the south (now the Intramuros district) and the Buddhist-Hindu settlement was ruled under Lakan Dula in northern Tundun (now in modern Tondo).[71] Islamization of Luzon began in the 16th century when traders from Brunei settled in the Manila area and married locals while maintaining kinship and trade links with Brunei and thus other Muslim centres in Southeast Asia. The Muslims were called "Moros" by the Spanish who assumed they occupied the whole coast. There is no evidence that Islam had become a major political or religious force in the region, with Father Diego de Herrera recording that the Moros lived only in some villages and were Muslim in name only.[26]

Economic activities

Historians widely agree that the larger coastal polities which flourished throughout the Philippine archipelago in the period immediately prior to the arrival of the Spanish colonizers (including Tondo and Maynila) were "organizationally complex", demonstrating both economic specialization and a level of social stratification which would have led to a local demand for "prestige goods".[7]

Specialized industries in the Tagalog and Kapampangan regions, including Tondo and Maynila, included agriculture, textile weaving, basketry, metallurgy, hunting, among others.[5] The social stratification which gave birth to the Maginoo class created a demand for prestige products including ceramics, textiles, and precious stones.[25] This demand, in turn, served as the impetus for both internal and external trade.

Junker notes that significant work still needs to be done in analyzing the internal/local supply and demand dynamics in pre-Spanish era polities, because much of the prior research has tended to focus on their external trading activities.[25] Scott notes that early Spanish lexicons are particularly useful for this analysis, because these early dictionaries captured many words which demonstrate the varied nuances of these local economic activities.[5]

Trade

Junker describes coastal polities of Tondo and Maynila's size as "administrative and commercial centers functioning as important nodes in networks of external and internal trade."[25] While the basic model for the movement of trade goods in early Philippine history saw coastal settlements at the mouth of large rivers (in this case, the Pasig river delta) controlling the flow of goods to and from settlements further upriver (in this case, the upland polities on the Laguna Lake coast),[25] Tondo and Maynila had trade arrangements which allowed them to control trade throughout the rest of the archipelago.[5] Scott observes that while the port of Tondo had the monopoly on arriving Chinese merchant ships, it was Manila's fleet of trading vessels which in turn retailed them to settlements throughout the rest of the archipelago, so much so that Manyila's ships came to be known as "Chinese" (sinina).[5]

Redistribution of Chinese goods

The most lucrative of Tondo's economic activities involved the redistribution of Chinese goods, which would arrive in Manila bay through Tondo's port and be distributed throughout the rest of the archipelago, mostly through Maynila's extensive shipping activities.[5]

The Chinese migrations to Malaya and the Philippines shore began in the 7th century and reached their peak after 1644 owing to the Manchu conquest of China. These Chinese immigrants settled in Manila, Pasig included, and in the other ports, which were annually visited by their trade junks, they have cargoes of silk, tea, ceramics, and their precious jade stones.[72]

According to William Henry Scott (1982), when ships from China came to Manila bay, Lakandula would remove the sails and rudders of their ships until they paid him duties and anchorage fees, and then he would then buy up all their goods himself, paying half its value immediately and then paying the other half upon their return the following year. In the interim, these goods would be traded throughout the rest of the archipelago. The end result was that other locals were not able to buy anything from the Chinese directly, but from Tondo[55] and Maynila,[5] who made a tidy profit as a result.

Augustinian Fray Martin de Rada Legaspi says that the Tagalogs were "more traders than warriors",[55] and Scott notes in a later book (1994)[5] that Maynila's ships got their goods from Tondo and then dominated trade through the rest of the archipelago. People in other parts of the archipelago often referred to Maynila's boats as "Chinese" (Sina or Sinina) because they came bearing Chinese goods.

Gold as a currency

Trade among the early Filipinos and with traders from the neighboring islands was conducted through Barter. The inconvenience of barter later led to the use of some objects as medium of exchange. Gold, which was plentiful in many parts of the islands,[73] invariably found its way into these objects that included the Piloncitos, small bead-like gold nuggets/bits considered by the local numismatists as the earliest coin of ancient Filipinos, and gold barter rings.[74]

The Piloncitos a type of gold ingots are small, some are of the size of a corn kernel—and weigh from 0.09 to 2.65 grams of fine gold. Large Piloncitos weighing 2.65 grams approximate the weight of one mass. Piloncitos have been excavated from Mandaluyong, Bataan, the banks of the Pasig River, and Batangas.[75] That gold was mined and worked here is evidenced by many Spanish accounts, like one in 1586 that said:

"The people of this island (Luzon) are very skillful in their handling of gold. They weigh it with the greatest skill and delicacy that have ever been seen. The first thing they teach their children is the knowledge of gold and the weights with which they weigh it, for there is no other money among them."[75]

Other than Piloncitos, the people of Tundun also used the Barter rings, which is gold ring-like ingots. These barter rings are bigger than doughnuts in size and are made of nearly pure gold.[76] Also, they are very similar to the first coins invented in the Kingdom of Lydia in present-day Turkey. Barter rings were circulated in the Philippines up to the 16th century.[77]

Agriculture

The people of Tondo engaged in agriculture,[5] making a living through farming, rice planting and aquaculture (especially in lowland areas). A report during the time of Miguel López de Legazpi noted of the great abundance of rice, fowls, wine as well as great numbers of carabaos, deer, wild boar and goat husbandry in Luzon. In addition, there were also great quantities of cotton and colored clothes, wax, wine, honey and date palms produced by the native peoples, rice, cotton, swine, fowls, wax and honey abound.

Crop production

Rice was the staple food of the Tagalog and Kapampangan polities, and its ready availability in Luzon despite variations in annual rainfall was one of the reasons Legaspi wanted to locate his colonial headquarters on Manila bay.[5] Scott's study of early Tagalog lexicons revealed that the Tagalogs had words for at least 22 different varieties of rice.[5]

In most other places in the archipelago, rootcrops served as an alternate staple in seasons when rice was not readily available.[5] These were also available in Luzon, but they were desired more as vegetables, rather than as a staple.[5] Ubi, Tugi, Gabi and a local root crop which the Spanish called Kamoti (apparently not the same as the sweet potato, sweet potato, Ipomoea batatas) were farmed in swiddens, while "Laksa" and "Nami" grew wild.[5] Sweet potatoes (now called Camote) were later introduced by the Spanish.[5]

Millet was common enough that the Tagalogs had a word which meant "milletlike": "dawa-dawa".

Animal husbandry

Duck culture was also practiced by the Tagalogs, particularly those around Pateros and where Taguig City stands today. This resembled the Chinese methods of artificial incubation of eggs and the knowledge of every phase of a duck's life. This tradition is carried on until modern times of making balut.[78]

Foreign relations

Maynila polity

By virtue of proximity, Tondo had a close and complex relationship with its neighbor-settlement, Maynila.[5] Tondo and Maynila shared a monopoly over the flow of Chinese tradeware throughout the rest of the archipelago,[5] with Tondo's port controlling the arrival of Chinese goods and Maynila retailing those goods to settlements throughout the rest of the archipelago.[5] Historical accounts specifically say that Maynila was also known as the "Kingdom of Luzon", but some scholars such as Potet[37] and Alfonso[79] suggest that this exonym may have referred to the larger area of Manila Bay, from Bataan and Pampanga to Cavite, which includes Tondo. Whatever the case, the two polities' shared alliance network saw both the Rajahs of Maynila and the Lakans of Tondo exercising political influence (although not territorial control) over the various settlements in what are now Bulacan and Pampanga.[23][5]

Notably, the 1521 account of "Prince" Ache,[80][5] who would later become Rajah Matanda,[19] cites a bitter territorial dispute between Maynila, then ruled by Ache's mother,[80][19] and Tondo, then ruled separately by Ache's cousin.[80][19] This conflict was enough to cause Ache to run away to his uncle, the Sultan of Brunei, in a bid to martial some military support as leverage against the Kingdom of Tondo.[80][81][5]

Butas, Tambobong and Macabebe

Tondo's relations with its neighboring settlements to the north are less clear, but the anonymous 1571 account translated by Blair and Robertson notes that the "neighboring village" of "Butas" (now called Navotas) acted independently of Tondo in 1571,[23][5] and allied itself with the leader of Macabebe during the Battle of Bangkusay.[23][5][79] Other sources mention another independent village, Tambobong was further north of Navotas. This is generally believed to be the origin of the present day city of Malabon.

Visayans

Tondo and Maynila are often portrayed as having adversarial relations with the polities of the Visayas, because of the disparaging comments of Rajah Sulayman towards the Visayan "pintados" during the earliest negotiations with Martin de Goiti in 1570.[23][5] Sulayman had boasted that the people of Maynila were "not like the Painted Visayans" and would not give up their freedoms as easily as the Visayans did.[23][5] Scott notes that at the very least, this meant that Sulayman had kept up-to-date with events happening in the Visayas,[15] probably arising from the trade relationships Tondo and Maynila had developed with polities throughout the archipelago.

Java

One of the primary source of Tondo's historiography—the Laguna Copperplate Inscription (c. 900 AD), was written using Kawi script, a writing system developed in Java. The inscription was written in Old Malay, with a few Sanskrit and Old Javanese elements, and many of the words in the inscription having equivalents in Tagalog.[2] This was a rare trace of Javanese influence that reached far flung island as far north as Luzon, which suggests the extent of interinsular exchanges of that time.[82]

The Dutch anthropologist Antoon Postma has concluded that the Laguna Copperplate Inscription contains toponyms that might be corresponding to certain places in modern Philippines; such as Tundun (Tondo); Pailah (Paila, now an enclave of Barangay San Lorenzo, Norzagaray); Binwangan (Binuangan, now part of Obando); and Puliran (Pulilan).[48] The toponym of Mdaŋ in particular, is interesting since it might correspond to the Javanese Kingdom of Mataram,[83] in present-day Indonesia, which flourished around the same period (c. 9th to 10th century). However, the nature of Tondo's relations with Java is not clear.

Siam

Several ceramic wares from Sukhothai and Sawankhalok were found in Luzon and Visayas region. The discovery of Siamese artifacts in the Philippines suggests that from c. 13th to 15th century, the exchanges between mainland Southeast Asia and the Philippine archipelago was established.[84][85]

Ming dynasty

The earliest Chinese historical reference to Tondo can be found in the "Annals of the Ming dynasty" called the Ming Shilu,[11] which record the arrival of an envoy from Luzon to the Ming dynasty in 1373.[11] Her rulers, based in their capital, Tondo (Chinese: 東都; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tong-to͘) were acknowledged not as mere chieftains, but as kings (王).[86] This reference places Tondo into the larger context of Chinese trade with the native people of the Philippine archipelago.

Theories such as Wilhelm Solheim's Nusantao Maritime Trading and Communication Network (NMTCN) suggest that cultural links between what are now China and the nations of Southeast Asia, including what is now the Philippines, date back to the peopling of these lands.[87] But the earliest archeological evidence of trade between the Philippine aborigines and China takes the form of pottery and porcelain pieces dated to the Tang and Song dynasties.[88]

The rise of the Ming dynasty saw the arrival of the first Chinese settlers in the archipelago. They were well received and lived together in harmony with the existing local population — eventually intermarrying with them so that today, numerous Filipinos have Chinese blood in their veins.[88] Also a lot of Philippine cultural mores today came from China more so than their later colonizers of Spain and the United States.[88]

This connection was important enough that when the Ming dynasty emperors enforced the Hai jin laws which closed China to maritime trade from 1371 to about 1567, trade with the Kingdom of Tondo was officially allowed to continue, masqueraded as a tribute system, through the seaport at Fuzhou.[89] Aside from this, a more extensive clandestine trade from Guangzhou and Quanzhou also brought in Chinese goods to Luzon.[90]

Luzon and Tondo thus became a center from which Chinese goods were traded all across Southeast Asia. Chinese trade was so strict that Luzon traders carrying these goods were considered "Chinese" by the people they encountered.[90]

Japan

.jpg.webp)

Relations between Japan and the kingdoms in the Philippines, date back to at least the Muromachi period of Japanese history, as Japanese merchants and traders had settled in Luzon at this time. Especially in the area of Dilao, a suburb of Manila, was a Nihonmachi of 3,000 Japanese around the year 1600. The term probably originated from the Tagalog term dilaw, meaning "yellow", which describes a colour. The Japanese had established quite early an enclave at Dilao where they numbered between 300 and 400 in 1593. In 1603, during the Sangley rebellion, they numbered 1,500, and 3,000 in 1606. In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of Japanese people traders also migrated to the Philippines and assimilated into the local population.[91] [92]

Japan was only allowed to trade once every 10 years. Japanese merchants often used piracy in order to obtain much sought after Chinese products such as silk and porcelain. Famous 16th-century Japanese merchants and tea connoisseurs like Shimai Soushitsu (島井宗室) and Kamiya Soutan (神屋宗湛) established branch offices on the island of Luzon. One famous Japanese merchant, Luzon Sukezaemon (呂宋助左衛門), went as far as to change his surname from Naya (納屋) to Luzon (呂宋).[93]

Timeline of historical events

Establishment (c. 1258)

The earliest date proposed for Maynila's founding is the year 1258, based on genealogical traditions documented by Mariano A. Henson in 1955.[94] (Later cited by Majul in 1973,[95] and by Santiago in 1990[96]) This tradition claims that a Majapahit settlement ruled by "Rajah Avirjirkaya" already existed in the Maynila at the time, and that it was attacked by a Bruneian commander named Rajah Ahmad, who defeated Avirjirkaya and established Maynila as a "Muslim principality".[94] The LCI provides evidence that Tondo existed at the time, but it is not explicitly mentioned in Henson's account.

The Bruneian Empire (c. 1500)

According to other Bruneian oral traditions,[5] a city with the Malay name of Selurong,[97] which would later become the city of Maynila)[97] was formed around the year 1500.[5]

Scott (1994) acknowledges those traditions, noting that "according to Bruneian folk history",[5]: 191 [ ] "Manila was probably founded as a Bornean trading colony about 1500, with a royal prince marrying into the local ruling family."[5]: 191 French linguist Jean-Paul Potet[37]: 122 notes, however, that "According to some, Luzon and/Manila would have been called Seludong or Selurong by the Malays of Brunei before the Spanish conquest (Cebu 1565, Manila 1571)."[37]: 122 However, Potet also points out that "there is no text to support this claim. Conversely, Borneo has a mountain site called Seludong."[37]: 122

According to yet other Bruneian oral traditions, the Sultanate of Brunei under Sultan Bolkiah attacked the kingdom of Tondo, and established Selurong[98] on the opposite bank of Pasig River. The traditional Rajahs of Tondo, like Lakandula, retained their titles and property but the real political power came to reside in the House of Soliman, the Rajahs of Maynila.[99]

Incorporation into the Bruneian Empire (1500)

Tondo became so prosperous that around the year 1500, the Bruneian Empire, under Sultan Bolkiah, merged it by a royal marriage of Gat Lontok, who later became Rajah of Namayan, and Dayang Kalangitan to establish a city with the Malay name of Selurong (later to become the city of Manila)[5][100] on the opposite bank of Pasig River.

The traditional rulers of Tondo, like Lakandula, retained their titles and property upon embracing Islam but the real political power transferred to the master trader House of Sulayman, the Rajahs of Maynila.[96]

Portuguese presence (1511 – 1540s)

The Portuguese first established a presence in Maritime Southeast Asia with their capture of Malacca in 1511,[101] and their contacts with the seafarers they described as Luções (lit. people from "lusong", the area now known as Manila Bay)[5] became the first European accounts of the Tagalog people,[102] as Anthony Reid recounts:

The first European reports on the Tagalogs classify them as "Luzons", a nominally Muslim commercial people trading out of Manila, and "almost one people" with the Malays of Brunei.[102]

The Portuguese chronicler Tome Pires noted that in their own country, the Luções had "foodstuffs, wax, honey, inferior grade gold", had no king, and were governed instead by a group of elders.[103] They traded with tribes from Borneo and Indonesia, and Filipino historians note that the language of the Luções was one of the 80 different languages spoken in Malacca.[104]

As skilled sailors, the Lucoes were actively involved in the political and military/naval affairs of those who sought to take control of the economically strategic highway of the Strait of Malacca, serving in the fleets of the Sultans of Ache[105] and Brunei,[106] and the former Sultan of Malacca,[107] Scholars have suggested that they may have served as highly skilled naval mercenaries sought after by various fleets of the time.[102]

Portuguese and Spanish accounts from the early[80][106] to mid[5] 1500s state that the Maynila polity was the same as the "kingdom"[Notes 7] that had been referred to as the "Kingdom of Luzon" (Portuguese: Luçon, locally called "Lusong"), and whose residents had been called "Luções".[80][106][5][19][79]

However, Kapampangan scholars such as Ian Christopher Alfonso[79] add that it is also possible that while the Portuguese and Spanish chroniclers specifically equated "Luçon" with Rajah Matanda's Maynila polity, the description may have been expansive enough to describe other polities in the Manila bay area, including Tondo as well as the Kapampangans of Hagonoy and Macabebe.[79]

Conflicts with Maynila (before 1521)

According to the account of Rajah Matanda as recalled by Magellan expedition members Gines de Mafra, Rodrigo de Aganduru Moriz, and expedition scribe Antonio Pigafetta,[5] Maynila had a territorial conflict with Tondo in the years before 1521.

At the time, Rajah Matanda's mother (whose name was not mentioned in the accounts) served as the paramount ruler of the Maynila polity, taking over from Rajah Matanda's father (also unnamed in the accounts),[5] who had died when Rajah Matanda was still very young.[80] Rajah Matanda, then simply known as the "Young Prince" Ache,[19] was raised alongside his cousin,[19] who was ruler of Tondo[80] – presumed by some[19] to be a young Bunao Lakandula, although not specifically named in the accounts.[5]

During this time, Ache realized that his cousin, who was ruler of the Tondo polity, was "slyly"[80] taking advantage of Ache's mother by taking over territory belonging to Maynila.[80] When Ache asked his mother for permission to address the matter, his mother refused, encouraging the young prince to keep his peace instead.[80] Prince Ache could not accept this and thus left Maynila with some of his father's trusted men, to go to his "grandfather", the Sultan of Brunei, to ask for assistance. The Sultan responded by giving Ache a position as commander of his naval force.[80]

In 1521, Prince Ache was coming fresh from a military victory at the helm of the Bruneian navy and was supposedly on his way back to Maynila with the intent of confronting his cousin when he came upon and attacked the remnants of the Magellan expedition, then under the command of Sebastian Elcano. Some historians[19][81][5] suggest that Ache's decision to attack must have been influenced by a desire to expand his fleet even further as he made his way back to Lusong and Maynila,[19] where he could use the size of his fleet as leverage against his cousin, the ruler of Tondo.[19]

Exclusion from the Battle of Manila (May 1570)

Tondo and its rulers were initially ignored by the Spanish during the conquest of Manila bay, because the Spanish focused their attention on Manila, which had fortifications that Tondo did not.[23][5]

While Spanish colonizers first arrived in the Philippines in 1521, the Spanish only reached the Manila Bay area and its settlements in 1570, when Miguel López de Legazpi sent Martín de Goiti to investigate reports of a prosperous Moro settlement on the island of Luzon.[23][5][19]

De Goiti arrived in mid-1570 and was initially well received by Maynila's ruler Rajah Matanda, who, as former commander of the Naval forces of Brunei, had already had dealings with the Magellan expedition in late 1521. Negotiations broke down, however, when another ruler, Rajah Sulayman, arrived and began treating the Spanish belligerently, saying that the Tagalog people would not surrender their freedoms as easily as the "painted" Visayans did.[23][5][19] The accounts of the De Goiti mission report that Tondo's ruler, Lakandula, sought to participate in these negotiations early on, but De Goiti intentionally ignored Lakandula because he wanted to focus on Maynila, which Legaspi wanted to use as a headquarters because it was already fortified, whereas Tondo was not.[23]

By May 24, 1570, negotiations had broken down, and according to the Spanish accounts, their ships fired their cannon as a signal for the expedition boats to return. Whether or not this claim was true, the rulers of Maynila perceived this to be an attack and as a result, Sulayman ordered an attack on the Spanish forces still within the city. The battle was very brief because it concluded with the settlement of Maynila being set ablaze.[23][5][19]

The Spanish accounts claim that De Goiti ordered his men to set the fire,[23] historians today still debate whether this was true. Some historians believe it is more likely that the Maynila forces themselves set fire to their settlement, because scorched-earth retreats were a common military tactic among the peoples of the Philippine archipelago at the time.[5]

De Goiti proclaimed victory, symbolically claimed Maynila on behalf of Spain, then quickly returned to Legaspi because he knew that his naval forces were outnumbered.[23][5] Contemporary writers believe the survivors of Maynila's forces would have fled across the river to Tondo and other neighboring towns.

Establishment of Maynila (May 1571)

López de Legazpi himself returned to assert the Spanish claim on Maynila a year later in 1571. This time, it was Lakandula who first approached the Spanish forces, and then Rajah Matanda. Rajah Sulayman was at first intentionally kept away from the Spanish for fear that Sulayman's presence might antagonize them.[23][5]

López de Legazpi began negotiating with Rajah Matanda and Lakandula to use Maynila as his base of operations, and an agreement was reached by May 19, 1571.[108] According to Spanish accounts, Sulayman began participating in the discussions again when he apologized to the Spanish for his aggressive actions of the previous year, saying that they were the product of his "youthful passion."[23][5] As a result of these talks, it was agreed that Lakandula would join De Goiti in an expedition to make overtures of friendship to the various polities in Bulacan and Pampanga, with whom Tondo and Maynila had forged close alliances.[23][5] This was met with mixed responses, which culminated in the Battle of Bangkusay Channel.

Battle of Bangkusay Channel (June 1571)

June 3, 1571, marked the last resistance by locals to the occupation and colonization by the Spanish Empire of Manila in the Battle of Bangkusay Channel. Tarik Sulayman, the chief of Macabebes, refused to ally with the Spanish and decided to mount an attack at the Bangkusay Channel on Spanish forces, led by Miguel López de Legazpi. Sulayman's forces were defeated, and he was killed. The Spanish victory in Bangkusay and Legaspi's alliance with Lakandula of the Kingdom of Tondo, enabled the Spaniards to establish themselves throughout the city and its neighboring towns.[109]

The defeat at Bangkusay marked the end of rebellion against the Spanish among the Pasig river settlements, and Lakandula's Tondo surrendered its sovereignty, submitting to the authority of the new Spanish capital, Manila.[110]

Tondo Conspiracy (1587–1588)

The Tondo Conspiracy of 1587–1588, also referred to as the "Revolt of the Lakans" and sometimes the "Conspiracy of the Maharlikas" was a plot against Spanish colonial rule by the Tagalog and Kapampangan nobles of Manila and some towns of Bulacan and Pampanga.[3] They were the indigenous rulers of their area or an area yet upon submission to the might of the Spanish was relegated as mere collector of tributes or at best Encomenderos that need to report to a Spanish governor. It was led by Agustín de Legazpi, the son of a Maginoo of Tondo (one of the chieftains of Tondo), born of a Spanish mother given a Hispanized name to appease the colonizers, grandson of conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi, nephew of Lakan Dula, and his first cousin, Martin Pangan. The datus swore to rise up in arms. The uprising failed when they were betrayed to the Spanish authorities by Antonio Surabao (Susabau) of Calamianes.[3] The mastermind of the plot was Don Agustín de Legazpi; the mestizo grandson of conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi, nephew of Lakan Dula, a relative of Rajah Matanda. Being a Moro, he was the son-in-law of Sultan Bolkieh of Brunei, whose first cousin was Martín Panga, the gobernadorcillo of Tondo.

Besides the two, the other leaders were Magat Salamat, son of Lakan Dula and the crown prince of Tondo; Juan Banal, another prince of Tondo and Salamat's brother-in-law; Geronimo Basi and Gabriel Tuambacar, brothers of Agustín de Legazpi; Pedro Balingit, the Lord of Pandakan; Felipe Salonga, the Lord of Polo; Dionisio Capolo (Kapulong), the Lord of Kandaba and brother of Felipe Salonga; Juan Basi, the Lord of Tagig; Esteban Taes (also Tasi), the Lord of Bulakan; Felipe Salalila, the Lord of Misil; Agustín Manuguit, son of Felipe Salalila; Luis Amanicaloa, another prince of Tondo; Felipe Amarlangagui, the commander-and-chief of Katanghalan; Omaghicon, the Minister of Nabotas, and Pitongatan (Pitong Gatang), another prince of Tondo and two governors from Malolos and Guiguinto.[3]

Notable rulers and nobles of Tondo

Historical rulers of Tondo

A number of rulers of Tondo are specifically identified in historical documents, which include:

- the epistolary firsthand accounts of the members of the Magellan and Legaspi expeditions, referred to in Spanish as "relaciones";[5]

- various notarized genealogical records kept by the early Spanish colonial government,[5] mostly in the form of last wills and testaments of descendants of said rulers;[19] and,

- in the case of Jayadewa, specific mention in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription.[2]

| Title | Name | Specifics | Dates | Primary source(s) | Academic reception of primary source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senepati | Unnamed | Senapati[47] (Admiral), known only in the LCI as the ruler who was represented by Jayadewa and the one who gave the pardon to Lord Namwaran and his relatives Dayang Angkatan and Buka for their excessive debts in c. 900 AD. | c. 900 CE[2] | Identified in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription as the ruler of Tondo in c. 900 CE | Identification as ruler of Tondo in c. 900 CE proposed by Antoon Postma[2] and generally accepted by Philippine historiographers[31] |

| Lakan or Lakandula | Bunao (Lakan Dula) | Bunao Lakandula, Lakan of Tondo and Sabag, he is the last ruler which possess the title of "Lakan". | Birth: – Death:c. 1575 "Three years after" Legazpi and Rajah Matanda, who both died in 1572."[5]: 192 Reign: c. 1570s and earlier |

Multiple firsthand accounts from the Legaspi Expedition (early 1570s); Spanish genealogical documents[19] | Firsthand accounts generally accepted by Philippine historiographers, with corrections for hispanocentric bias subject to scholarly peer review;[5][31] veracity of genealogical documents subject to scholarly peer review.[19][31] |

| Don[5] (Presumably Lakan, but the actual use of the term is not recorded in historical documents.)[19] |

Agustin de Legaspi | The last indigenous ruler of Tondo; son of Rajah Sulayman, proclaimed Paramount Ruler of Tondo after the death of Bunao Lakan Dula. Co-instigator of the 1588 Tondo conspiracy along with his cousin Magat Salamat (Lakan Dula's son); caught and executed by the Spanish, resulting in the dissolution of the office of Paramount Ruler.[5] | 1575–1589 | Firsthand accounts of the Legaspi Expedition (mid-1570s); Spanish genealogical documents[19] | Firsthand accounts generally accepted by Philippine historiographers, with corrections for hispanocentric bias subject to scholarly peer review;[5][31] veracity of genealogical documents subject to scholarly peer review.[19][31] |

Legendary rulers

A number of rulers of Tondo are known only through oral histories, which in turn have been recorded by various documentary sources, ranging from historical documents describing oral histories, to contemporary descriptions of modern (post-colonial/national-era) oral accounts. These include:

- orally transmitted genealogical traditions, such as the Batu Tarsila, which have since been recorded and cited by scholarly accounts;

- legends and folk traditions documented by anthropologists, local government units, the National Historical Institute of the Philippines, and other official sources; and

- recently published genealogical accounts based on contemporary research.

Scholarly acceptance of the details recounted in these accounts vary from case to case, and are subject to scholarly peer review.

| Title | Name | Specifics | From | Primary sources | Academic notes on primary sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Princess" or "Lady" (term used in oral tradition, as documented by Odal-Devora)[38] | Sasaban | In oral tradition recounted by Nick Joaquin and Leonardo Vivencio, a "lady of Namayan" who went to the Majapahit court to marry Emperor Soledan, eventually giving birth to Balagtas, who then returned to Namayan/Pasig in 1300.[38]: 51 | prior to 1300[38] | Oral Tradition cited by Leonardo Vivicencio and Nick Joaquin[38] | Cited in non-academic work by Nick Joaquin, then later mentioned in Odal-Devora, 2000.[38] |

| "Princess" or "Lady" (term used in oral tradition, as documented by Odal-Devora)[38] | Panginoan | In Batangueño Folk Tradition as cited by Odal-Devora,[38] the daughter of Kalangitan and Lontok who were rulers of Pasig, who eventually married Balagtas, King of Balayan and Taal.: 51 In Kapampangan[38] Folk Tradition as cited by Odal-Devora,[38] who eventually married Bagtas, the "grandson of Kalangitan.": 47, 51 In oral tradition recounted by Nick Joaquin and Leonardo Vivencio, "Princess Panginoan of Pasig" who was married by Balagtas, the son of Emperor Soledan of Majapahit in 1300 in an effort consolidate rule of Namayan.[38]: 47, 51 | c. 1300[38] | Batangueño folk tradition, Kapampangan folk tradition, Oral tradition cited by Vivencio and Joaquin[38] | Mentioned in Odal-Devora, 2000;[38] also mentioned in non-academic work by Nick Joaquin[38] |

| Rajah | Lontok | Rajah Lontok was the husband and co-regent of Dayang Kalangitan. During his reign, Tondo had many achievements and became more powerful; his reign also saw the enlargement of the state's territory.[38] | c.1450-1500? | Kapampangan folk tradition[38] | – |

| Dayang or Sultana | Kalangitan[38] | Legendary "Lady of the Pasig"[38] who ruled Namayan and later became the grandmother of the Kapampangan ruler known as "Prinsipe Balagtas"[38] | Legendary antiquity / c.1450–c.1500 | Kapampangan folk tradition[38] | – |

| Sultan | Bolkiah[111][5] | Sultan Bolkiah, according to Brunei folk history, is the "Nakhoda Ragam" or the "Singing Captain", the reputed conqueror of the Philippines.[5] The tradition even names the cannon with which he was said to have taken Manila – "Si Gantar Alam", translated as the "Earth-shaking Thunderer".[5] He established an outpost in the center of the area of Manila after the rulers of Tondo lost in the Battle of Manila (1500). According to this legend, Sultan Bolkiah of Brunei is the grandfather of Ache, the old rajah, also known as Ladyang Matanda or Rajah Matanda.[19] | c. 1500–1524 | – | – |

Nobles associated with Tondo

| Title | Name | Specifics | Dates | Primary sources | Academic notes on primary sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hwan (possibly "Honourable" or "Lord")[2] | Namwaran | Probable[2] person-name mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, as the ancestor of Namwaran and Bukah and original debtor of the transaction in question.[2] The title "Hwan" is translated "Honourable" or "Lord" in different lines of the LCI, depending on context. | c. 900 AD | Translation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription by Antoon Postma | |

| Dayang[2] | Angkatan | Probable[2] person-name mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, as the descendant (daughter) of Namwaran. Related through Namwaran to Bukah.[2] | c. 900 AD | Translation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription by Antoon Postma | |

| Bukah | Probable[2] person-name mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, as the descendant of Namwaran related to the Lady (Dayang) Angkatan[2] | c. 900 AD | Translation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription by Antoon Postma | ||

| Kasumuran[2] (uncertain) |

Possible[2] person-name mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription. The word may either be a reference to a Lord Minister or a reference to an ancient name of the Southeast coast region of Laguna Lake | c. 900 AD | Translation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription by Antoon Postma | Identified by Postma as possibly being either a place-name or a person-name.[2] Possible reference the Southeast coast region of Laguna Lake proposed by Tiongson[50][51] | |

| Gat[2] | Bishruta[2] | Probable[2] person-name mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, as the representative of the Lord Minister of "Binwagan"[2] | c. 900 AD | Translation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription by Antoon Postma | Postma's conclusions about the Bulacan location of Binwagan have been questioned by local Laguna historian Tiongson (2006)[50][51] |

| Ganashakti[2] | Probable[2] person-name mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, as the representative of Jayadewa, Lord Minister of "Pailah"[2] | c. 900 AD | Translation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription by Antoon Postma | Postma's conclusions about the Bulacan location of Pailah have been questioned by local Laguna historian Tiongson (2006)[50][51] | |

| Datu | Magat Salamat | Co-instigator of the 1588 "Conspiracy of the Maharlikas," son of Bunao Lakan Dula who served as datu under his cousin and co-instigator, Rajah Sulayman's son Agustin de Legaspi who had been pronounced Paramount Ruler over the datus of Tondo after the death of Lakandula.[5] | c. 1588 | Firsthand accounts of the Legaspi Expedition (mid-1570s); Spanish genealogical documents[19] | Firsthand accounts generally accepted by Philippine historiographers, with corrections for hispanocentric bias subject to scholarly peer review;[5][31] veracity of genealogical documents subject to scholarly peer review.[19][31] |

| Luis Amanicaloa[112] | Participant in the 1588 "Conspiracy of the Maharlikas." Member of the Maginoo class from Tondo. | c. 1588 | |||

| Felipe Amarlangagui[112] | Participant in the 1588 "Conspiracy of the Maharlikas." Member of the Maginoo class from Katanghalan. | c. 1588 | |||

| Lord Balingit[112] | Participant in the 1588 "Conspiracy of the Maharlikas." The Datu of Pandakan | c. 1588 | |||

| Pitongatan (Pitong-gatang)[112] | Participant in the 1588 "Conspiracy of the Maharlikas." Member of the Maginoo class from Tondo. | c. 1588 | |||

| Kapulong[112] | Participant in the 1588 "Conspiracy of the Maharlikas." Member of the Maginoo class from Candaba, Pampanga. | c. 1588 | |||

| Juan Basi[112] | Participant in the 1588 "Conspiracy of the Maharlikas." The Datu of Tagig (Taguig) | c. 1588 | |||

| Esteban Taes (also known as Ginoong Tasi)[112] | Participant in the 1588 "Conspiracy of the Maharlikas." A Datu from Bulacan. | c. 1588 |

Notable sources

Laguna Copperplate Inscription (c. 900 CE)

The first reference to Tondo occurs in the Philippines' oldest historical record — the Laguna Copperplate Inscription (LCI). This legal document was written in Kawi, and dates back to Saka 822 (c. 900).

The first part of the document says that:

On this occasion, Lady Angkatan, and her brother whose name is Bukah, the children of the Honourable Namwaran, were awarded a document of complete pardon from the King of Tundun, represented by the Lord Minister of Pailah, Jayadewa.

The document was a sort of receipt that acknowledged that the man named Namwaran had been cleared of his debt to the King of Tundun, which in today's measure would be about 926.4 grams of gold.[2][47]

The article mentioned that other places in the Philippines and their rulers: Pailah (Lord Minister Jayadewa), Puliran Kasumuran (Lord Minister), Binwangan (unnamed). It has been suggested that Pailah, Puliran Kasumuran, and Binwangan are the towns of Paila, Pulilan, and Binwangan in Bulacan, but it has also been suggested that Pailah refers to the town of Pila, Laguna. More recent linguistic research of the Old Malay grammar of the document suggests the term Puliran Kasumuran refers to the large lake now known as Laguna de Ba'y (Puliran), citing the root of Kasumuran, *sumur as Old Malay for well, spring or freshwater source. Hence ka-sumur-an defines a water-source (in this case the freshwater lake of Puliran itself). While the document does not describe the exact relationship of the King of Tundun with these other rulers, it at least suggests that he was of higher rank.[113]

Ming dynasty court records (c. 1300s)

The next historical reference to Ancient Tondo can be found in the Ming Shilu Annals (明实录]),[11] which record the arrival of an envoy from Luzon to the Ming dynasty (大明朝) in 1373.[11] Her rulers, based in their capital, Tondo (Chinese: 東都; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tong-to͘) were acknowledged not as mere chieftains, but as kings (王).[86] This reference places Tondo into the larger context of Chinese trade with the native people of the Philippine archipelago.

Theories such as Wilhelm Solheim's Nusantao Maritime Trading and Communication Network (NMTCN) suggest that cultural links between what are now China and the nations of Southeast Asia, including what is now the Philippines, date back to the peopling of these lands.[87] But the earliest archeological evidence of trade between the Philippine aborigines and China takes the form of pottery and porcelain pieces dated to the Tang and Song dynasties.[88][114]

Firsthand Spanish accounts (1521 – late 1500s)

Events that took place in the Pasig river delta in the 1500s are documented in some of the firsthand epistolary accounts ("relaciones") written by the Spanish.[19][5]

Most of these describe events that took place after 1571–72, when forces under the command of Martín de Goiti, and later Miguel de Legazpi himself, arrived in Manila Bay. These are described in the numerous accounts of the Legazpi expedition, including those by the expedition's designated notary Hernando de Riquel, by Legazpi's successor Guido de Lavezares, and by Legazpi himself.[5]

However, there are also some references to Maynila, Luzon, and Tondo[5] in the accounts of the Magellan expedition in 1521, which, under the command of Sebastian Elcano, had captured a commander of naval forces for the Sultan of Brunei, whom the researchers William H. Scott[5] and Luis Dery[19] identified as Prince Ache, who would later become Rajah Matanda.[5][19] These events, and the details Ache's interrogation,[5] were recorded in accounts of Magellan and Elcano's men, including expedition members Rodrigo de Aganduru Moriz,[80] Gines de Mafra, and the expedition's scribe Antonio Pigafetta.[106]

Many of these relaciones were later published in compilations in Spain,[5] and some were eventually translated and compiled into the multi-volume collection "The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898" by Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson.[5]

Early Tagalog lexicons (late 1500s – early 1600s)

In addition to the extensive descriptions contained in the firsthand accounts of the Spanish expeditions, much[5] of what is now known about precolonial Tagalog culture, religion, and language are derived from early Tagalog dictionaries and grammar books, such as Fray San Buenaventura's 1613 "Vocabulario de la lengua tagala" and Fray Francisco Blancas de San José's 1610 "Arte de la lengua tagala." Scott notes that while the relaciones spoke much about the Tagalogs' religion because it was the concern of the Spanish missionaries, and of their political and martial organization because it was the concern of the Spanish bureaucrats,[5] these dictionaries and grammar books are rich sources of information regarding the Tagalogs' material and ephemeral culture.[5]

Notable genealogical sources

Historical documents containing genealogical information regarding the rulers of Tondo during and immediately after the arrival of the Spanish fleet in the early 1570s mostly consist of notarized Spanish documents[19] executed by the direct descendants of rulers such as (Bunao) Lakan Dula of Tondo; Rajah Matanda (Ache) and Rajah Sulayman of Maynila; and Rajah Calamayin of Namayan.[19] In addition to firsthand accounts of the executors' immediate descendants and relatives, some (although not all) of these genealogical documents include information from family oral traditions, connecting the document's subjects to local legendary figures.[19] Several of these notarized Spanish documents are kept by the National Archives and are labeled the "Lakandula documents".[19]