Pietro Andrea Mattioli

Pietro Andrea Gregorio Mattioli (Italian: [ˈpjɛːtro anˈdrɛːa ɡreˈɡɔːrjo matˈtjɔːli]; 12 March 1501 – c. 1577) was a doctor and naturalist born in Siena.

Biography

He received his MD at the University of Padua in 1523, and subsequently practiced the profession in Siena, Rome, Trento and Gorizia, becoming personal physician of Ferdinand II, Archduke of Further Austria in Prague and Ambras Castle, and of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna.

Mattioli described the first case of cat allergy. His patient was so sensitive to cats that if he was sent into a room with a cat he reacted with agitation, sweating and pallor.

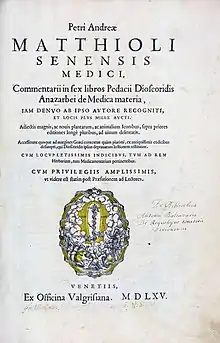

A careful student of botany, he described 100 new plants and coordinated the medical botany of his time in his Discorsi ("Commentaries") on the De Materia Medica of Dioscorides. The first edition of Mattioli's work, the Italian translation of De Materia Medica, supplemented with his own commentaries, appeared in 1544 in Venice. There were several later editions in Italian. In 1554 the first edition of the Commentarii appeared in Latin, accompanied by a Latin translation of Dioscorides' work that differed only little from the Latin translation that Jean Ruel had published in 1516, and that had served as the basis for Mattioli's Italian translation. The Commentarii were translated into French (Lyon, 1561), Czech (Prague, 1562), and German (Prague, 1563).

In addition to identifying the plants originally described by Dioscorides, Mattioli added descriptions of some plants not in Dioscorides and not of any known medical use, thus marking a transition from the study of plants as a field of medicine to a study of interest in its own right. In addition, the woodcuts in Mattioli's work were of a high standard, allowing recognition of the plant even when the text was obscure. A noteworthy inclusion is an early variety of tomato, the first documented example of the vegetable being grown and eaten in Europe.[1]

In 1703 Charles Plumier named a plant genus Matthiola in honor of Mattioli.[2] This name was adopted by Linnaeus in 1753.[3] The genus was later placed in the plantfamily Rubiaceae. In 1812 William Townsend Aiton named a plant genus Mathiola, also in honor of Mattioli.[4] This genus is now placed in the Brassicaceae. Aiton's name was later conserved against the earlier name of Linnaeus, with the conserved spelling Matthiola.[5]

Mattioli argued against Fracastoro's theory of fossils, as well as against his own conclusions, as described as follows in Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology:

The system of scholastic disputations encouraged in the Universities of the middle ages had unfortunately trained men to habits of indefinite argumentation, and they often preferred absurd and extravagant propositions, because greater skill was required to maintain them; the end and object of such intellectual combats being victory and not truth. ...Andrea Mattioli, for instance, an eminent botanist, the illustrator of Dioscorides, embraced the notion of Agricola, a German miner, that a certain 'materia pinguis' or 'fatty matter,' set into fermentation by heat, gave birth to fossil organic shapes. Yet Mattioli had come to the conclusion, from his own observations, that porous bodies, such as bones and shells, might be converted into stone, as being permeable to what he termed the 'lapidifying juice.[6]

Legacy

Pietro Andrea Mattioli was a renowned botanist and physician, and this is attested to by his published works. As Mattioli held a post in the Imperial Court as physician to Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria, and the Emperor Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor, this granted him immense influence. But some of his practice included the frequent testing of the effects of poisonous plants on prisoners in order to popularize his works--no doubt a common practice at the time.[7] And Mattioli did not tolerate either rivals or corrections. The naturalists and physicians who dared to disagree or correct him did so at their peril. The list of some of the most important men of the day that were admonished, rebuked, or pursued by the Inquisition contains Wieland, Anguillara, Gesner, Lusitanus and others. This caused the long-term domination of Mattioli's version of De Materia Medica throughout the continent, especially in northern Europe.[8]

Works

- 1533, Morbi Gallici Novum ac Utilissimum Opusculum

- 1535, Liber de Morbo Gallico, dedicated to Bernardo Clesio

- 1536, De Morbi Gallici Curandi Ratione

- 1539, Il Magno Palazzo del Cardinale di Trento

- 1544, Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo Libri cinque Della historia, et materia medicinale tradotti in lingua volgare italiana da M. Pietro Andrea Matthiolo Sanese Medico, con amplissimi discorsi, et comenti, et dottissime annotationi, et censure del medesimo interprete, also known as Discorsi

- 1548, Italian translation of Geografia di Tolomeo

- 1554, Petri Andreae Matthioli Medici Senensis Commentarii, in Libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei, de Materia Medica, Adjectis quàm plurimis plantarum & animalium imaginibus, eodem authore, also known as Commentarii. This Materia Medica work had anonymous commentaries by Michael Servetus, and it is known as "Lyon printers tribute to Michael de Villanueva."[9]

- 1558, Petri Andreae Matthioli senensis, serenissimi Principis Ferdinandi Auchiducis Austriae &c. Medici, commentarii secundo aucti, in libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei de medica materia : adjectis quam plurimis Plantarum, & Animalium Imaginibus quae in priore Editione non-habentur, eodem Authore Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- 1558, Apologia Adversus Amatum Lusitanum (attached to the Digital edition above)

- 1561, Epistolarum Medicinalium Libri Quinque

- Commentarii in sex libros Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei de medica materia (in Latin). Venezia: Vincenzo Valgrisi. 1565.

- 1568, I discorsi di m. Pietro Andrea Matthioli sanese, medico cesareo, et del serenissimo principe Ferdinando archiduca d'Austria &c. nelli sei libri di Pedacio Discoride Anazarbeo della materia medicinale. Venezia: Vincenzo Valgrisi. A copy for the Duke of Urbino, Francesco Maria II della Rovere, coloured and decorated with landscape backgrounds by Gherardo Cibo is now kept in the Biblioteca Alessandrina in Rome (Rari 278).[10] Digital edition by the Italian Ministero della Cultura.

- 1569, Opusculum de Simplicium Medicamentorum Facultatibus

- 1571, Compendium de Plantis Omnibus una cum Earum Iconibus

- De plantis (in Latin). Venezia: Vincenzo Valgrisi. 1571.

- 1586, De plantis epitome. Francofurti ad Moenum Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- De plantis (in Latin). Frankfurt am Main: Johann Feyerabend. 1586.

- 1590, Kreutterbuch deß hochgelehrten unnd weitberühmten Herrn D. Petri Andreae Matthioli : jetzt widerumb mit viel schönen neuwen Figuren, auch nützlichen Artzeneyen, und andern guten Stücken, zum andern mal auß sonderm Fleiß gemehret und verfertigt. Franckfort am Mayn : [Johann Feyerabend für Peter Fischer & Heinrich Tack]. Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- 1598, Medici Caesarei et Ferdinandi Archiducis Austriae opera quae extant omnia . Frankfurt a.M. Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- 1627, Les commentaires de P. André Matthiolus sur les six livres de Pedacius Dioscoride Anazarbeen, de la matiere medecinale : traduits de latin en françois, par M. Antoine du Pinet ; et illustrez de nouveau, d'un bon nombre de figures, & augmentez ... ; avec plusieurs tables ... . Lyon Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

References

- McCue, George Allen (1952). "The History of the Use of the Tomato: An Annotated Bibliography". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 39 (4): 291–292. doi:10.2307/2399094. JSTOR 2399094.

- Plumier, C. (1703). Nova plantarum americanarum genera. apud Joannem Boudot. p. 16.

- Linnaeus, C. (1753). Species plantarum. Vol. 2. p. 1192.

- Aiton, W.T. (1812). Hortus kewensis. Vol. 4 (2 ed.). Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. p. 119.

- ICN Chenzhen Code, Appendix III E.2

- Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, 1832, p.29

- Le Wall, Charles. The Curious Lore of Drugs and Medicines: Four Thousand Years of Pharmacy. (Garden City, New York: Garden City Publishing Co. Inc: 1927) and Riddle, John M.Dioscorides on pharmacy and medicine. (Austin: University of Texas Press,1985)

- Genaust, Helmut (1976). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der botanischen Pflanzennamen ISBN 3-7643-0755-2

- Michael Servetus Research Archived 2012-11-13 at the Wayback Machine Website with graphical study on the Materia Medica of 1554 by Mattioli and Michael "Servetus"

- Tongiorgi Tomasi, Lucia (2021). "Plants, Landscapes, Colours. The Life, Writings and Works of Gherardo Cibo". Mattioli's Dioscorides illustrated by Cibo. Barcelona: M. Moleiro Editor. pp. 13–65. ISBN 9788416509676.

- International Plant Names Index. Mattioli.

- Isely, Duane (2002). One Hundred and One Botanists. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. pp. 26–28. ISBN 978-1-55753-283-1. OCLC 947193619.