Andrew J. Thomas

Andrew Jackson Thomas (1875–1965) was a self-taught American architect who was known for designing low-cost apartment complexes that included green areas in the first half of the twentieth century.

Andrew Jackson Thomas | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1875 Manhattan, New York |

| Died | 1965 |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Known for | Low-cost apartments with green space |

Biography

Andrew Jackson Thomas was born on Lower Broadway in Manhattan, New York, in 1875. Thomas was the son of a dealer in oil paintings and diamonds. His mother died when he was twelve.[1] He was an orphan by the age of 13.[2] Thomas spent some time working in the Yukon gold fields, and worked as a rent collector in the Columbus Avenue tenements in New York. He obtained a job as a timekeeper for a building contractor, where he became interested in construction plans. He was able to use his self-taught knowledge to launch a career as an architect.[3]

Thomas became identified with the idea of including gardens in apartment complexes as early as the 1910s.[4] During World War I (1914–1918) the United States Shipping Board set up the Emergency Fleet Corporation to finance expansion of shipyards. Among its responsibilities were building housing for workers. Thomas was among those employed in the housing division.[5] As supervising architect for the Emergency Fleet Corporation, Thomas became expert in finding ways to minimize costs.[6] After the war Thomas was architect for a number of projects for the Queensboro Corporation, including important work in Jackson Heights, Queens.[7] He also worked directly for Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.[3]

John D. Rockefeller Jr. noticed Thomas's work and employed him to design the Dunbar Apartments (1926–1928), a non-profit cooperative for African Americans in Harlem. Thomas later was appointed the New York State Architect. He designed several hospitals, including the Coney Island Hospital in Brooklyn.[8] A 1931 story on Thomas said he was "of medium height, bald, and a bit round. Better housing is his religion and he talks about it with the fervor of Billy Sunday."[1] Andrew Jackson Thomas died in 1965.[3]

An entrepreneur, Thomas's skills included proselytizing and organizing. Unlike many other architects, Thomas saw multiple-dwelling units as homes. He was uninterested in classicist exterior designs, but looked to sources such as Italian villas and Spanish farmhouses for inspiration.[6] Talking of his Linden Court complex, the architectural critic John Taylor Boyd Jr. said:

It is evident that the block has been designed as a whole in a simple, but comprehensive, and highly coordinated architectural design.... [The garden's] benefits are apparent when it is remembered that the streets are the only playground of New York children, including the children of the rich; even the luxurious Park Avenue apartment houses make a poor showing in this respect....It is evident that from the point of view of convenience, comfort, cheerfulness, even of beauty, this group closely approaches an ideal type of housing....As architecture goes, it could hardly be improved upon.[9]

Garden Apartments

In 1919 Thomas was a member of the jury of a competition launched by New York State for a plan to rehabilitate a tenement block on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Thomas argued in favor of demolition and new construction, saying that the costs of rehabilitation were higher while the standards were lower. Others argued that it was not realistic to demolish 50,000 tenements that had been built under older construction standards, so ways had to be found to upgrade them.[10] Starting in 1919, Thomas advocated construction of U-shaped tenement buildings surrounding interior gardens. The configuration maximized light and air, but kept construction cost to the minimum compared to other configurations. A greater return on investment would be delivered compared to other configurations with less open space.[11] Thus Thomas's entry to the 1921 tenement house competition, sponsored by the Phelps Stokes Fund, featured a large central court. However, it was disqualified because the buildings only covered 60% of the lot.[12]

In a typical Thomas design, twelve U-shaped buildings would be arranged round the perimeter of a central open space. Thomas designed several clusters at Jackson Heights such as Linden Court and the Château as cooperatives for upper-middle income residents.[13] Linden Court, built in 1919-1821 by the Queensboro Corporation to Thomas's design, is on 84th and 85th streets between 37th and Roosevelt avenues. The buildings in the complex are in attached pairs around the perimeter of a shared open space holding a landscaped garden, with gaps at regular intervals in the perimeter wall. The layout provides light and ventilation to the apartments, and fosters a sense of belonging to a community.[14] Linden Court was the first development to include parking spaces, with single-story garages accessed via narrow driveways.[15] The elegant Château cooperative apartment complex was built in French Renaissance style. The twelve buildings surround a large common garden. They have slate mansard roofs pierced by dormer windows, and diaperwork brick walls.[16]

In 1919 the Corporation introduced the concept of cooperative ownership to strengthen this sense of community. Other examples of garden apartment blocks designed by Thomas around this time are the Chateau (1922) on 80th and 81st streets south of 34th avenue and the Towers (1923) on the block just north of the Chateau.[17] New York legislation passed in 1922 let life insurance companies invest in housing projects.[18] However, no more than $9 per month could be charged for a room. By 1924 the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company had funded a housing project designed by Thomas in Long Island City, Queens. Fifty-four buildings, using a modified version of his U prototype designed to minimize costs, provided accommodation for 2,125 low-income families.[19]In 1924 the Queensboro Corporation started the Ivy Court, Cedar Court, and Spanish Gardens projects, all designed by Thomas.[20]

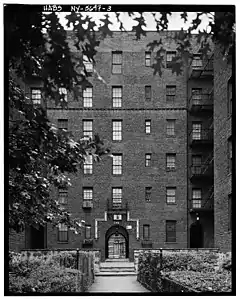

The 1928 Thomas Garden Apartments project in the Bronx with 170 middle-income 5-story walk-up units was started by a union consortium and completed by John D. Rockefeller Jr. The sloping interior garden reflected Japanese concepts and included running water and bridges.[21] The Paul Lawrence Dunbar Apartments were completed in Harlem in 1928.[22] Also built by Rockefeller, the cooperative was limited to blacks, while the Thomas Gardens had been limited to whites. It contained 511 well-lit and well-ventilated apartments around a large central space. The many protrusions into the interior space created many corner rooms and double-exposure apartments. The structure could be seen as a defensive enclosure protected from the deteriorating external neighborhood.[23] The apartments were named after the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. Notable Harlem residents who moved to the complex included W. E. B. Du Bois, A. Philip Randolph, Paul Robeson and Bill Robinson.[24]

Thomas's Dunolly Gardens (1939) on the block between 78th and 79th streets and 34th and 35th avenues are an atypical garden apartment complex where the architecture has a more modernistic appearance.[17] The corner windows, considered very innovative in the 1930s, lent a Moderne/Art Deco style to the exteriors, and gave the apartment interiors a more spacious feeling. As the last garden apartment project in his career, Dunolly Gardens' represents perhaps Thomas's crowning achievement in providing expertly laid-out, light and air-filled apartments, sharing the interior, common garden space that typify the Jackson Heights historic district. [25]

Other projects

Thomas designed Millan House in Lenox Hill, built in 1930–1931.[26]

Thomas designed the Princeton Inn Hotel, now Forbes College at Princeton University, built between 1923 and 1924.[27]

Andrew J. Thomas was selected architect for the Forest Hill neighborhood, an ambitious planned community to be built in part of John D. Rockefeller's estate in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, which his son had bought in 1923. It was expected to be a model of urban development targeting young professionals and executives of Standard Oil.[28] The development was to include apartments and a commercial sector, including the Heights Rockefeller Building, a commercial and office building, which was completed by early 1930. 600 houses would be built to a small number of models, placed in pairs that mirrored each other.[29] The houses were conceived as a village of Norman farmhouses, but were built to the highest standards of the day using the best materials, with innovations such as first-floor laundry rooms, basement living space where the children could play and multiple bathrooms. The houses had basement-level two-car garages, often sharing a driveway between two houses. The houses were landscaped before going on the market, and the property deeds included strict limitations on visible external changes such as fences and outbuildings. African Americans and Jewish people were not at first allowed to purchase houses.[28] Construction began at the end of 1929, but most work stopped from 1931 to 1938 during the Depression. Only 81 of the planned 600 houses were actually built. In 1986, they were placed in the National Register of Historic Places.[28]

Bibliography

- Thomas, Andrew Jackson; Chamberlin, Noel (1924). The Towers: Jackson Heights. The Corporation. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Thomas, Andrew Jackson (1925). Industrial Housing. Bayonne, N.J.: The Bayonne housing corporation. pp. 61.

- Thomas, Andrew Jackson; Goodman, Percival (1946). Riverview: A Proposed Residential Community, Long Island City, New York. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

Gallery

Forbes College, Princeton, from College Road West - Originally Princeton Inn (1923-1924)

Forbes College, Princeton, from College Road West - Originally Princeton Inn (1923-1924) Heights Rockefeller Building (1930)

Heights Rockefeller Building (1930) Coney Island Hospital, Brooklyn (1954)

Coney Island Hospital, Brooklyn (1954)

References

Notes

- Leslie, Leslie & Sedgwick 1931, p. 140.

- Plunz 1990, p. 124.

- Urbanelli & Robins 1993, p. 24.

- Gray 2011.

- Urbanelli & Robins 1993, p. 10.

- Architectural Record 1991, p. 160.

- Urbanelli & Robins 1993, p. 15.

- Urbanelli & Robins 1993, p. 25.

- Urbanelli & Robins 1993, p. 26.

- Plunz 1990, p. 127.

- Plunz 1990, p. 137.

- Plunz 1990, p. 136.

- Plunz 1990, p. 141.

- Urbanelli & Robins 1993, p. 3.

- New York Landmarks Preservation Commission 2008, p. 300.

- New York Landmarks Preservation Commission 2008, p. 299.

- Urbanelli & Robins 1993, p. 4.

- Plunz 1990, p. 150.

- Plunz 1990, p. 151.

- Urbanelli & Robins 1993, p. 16.

- Plunz 1990, p. 155-156.

- Plunz 1990, p. 159.

- Plunz 1990, p. 160.

- New York Landmarks Preservation Commission 2008, p. 204.

- White, Willensky & Leadon 2010, p. 768.

- Gray 2011

- Maynard 2012, p. 249.

- Levenson 2012.

- Morton 2002, p. 66.

Sources

- Architectural Record. McGraw-Hill. 1991. p. 160. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- Gray, Christopher (July 14, 2011). "Dr. Dolittle's Kind of Co-op". New York Times. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- Leslie, Frank; Leslie, Miriam Florence; Sedgwick, Ellery (1931). The American Magazine. Frank Leslie Publishing House. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- Maynard, William Barksdale (13 May 2012). Princeton: America's Campus. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-05085-0. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Levenson, Roberta Malbin (2012). "Historic Rockefeller Home". Cleveland History Lessons. Archived from the original on 2011-06-24. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- Morton, Marian J. (1 August 2002). Cleveland Heights: The Making of an Urban Suburb. Arcadia Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7385-2384-2. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- New York Landmarks Preservation Commission (2008-12-03). Guide to New York City Landmarks. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- Plunz, Richard (1990). A History of Housing in New York City: Dwelling Type and Social Change in the American Metropolis. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-06297-8. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- Urbanelli, Elisa; Robins, Anthony W. (October 19, 1993). "Jackson Heights Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010-06-09). AIA Guide to New York City. Oxford University Press. p. 768. ISBN 978-0-19-538386-7. Retrieved 2013-01-08.