Anglo-French War (1294–1303)

The Anglo-French War (in French: Guerre de Guyenne) was a conflict between 1294–98 and 1300–03 revolved around Gascony. The Treaty of Paris (1303) ended the conflict.

| Anglo-French War 1294-1303 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

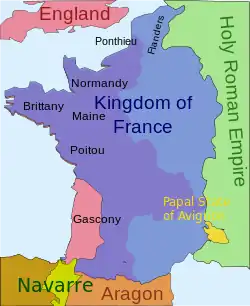

France in 1328 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Aquitaine & Gascony

Serious conflict was precipitated in 1293, when clashes between French and English seamen caused Philip IV of France to summon his vassal to Parlement. When Gascon castles occupied by the French as part of the settlement were not returned to the English on schedule, Edward I of England renounced his homage and prepared to fight for Aquitaine. The war that ensued (1294–1303) went in favour of Philip the Fair, whose armies thrust deep into Gascony.

Flanders

Edward retaliated by allying with Flanders and other northern princes. He launched a campaign in concert with the Count of Flanders in August 1297, but met defeat from a French force led by Robert II, Count of Artois, and during a truce from October 1297 to 1303 the rival monarchs reestablished the status quo ante.[1] The peace of 1303 carried all a potential for conflict, by returning the duchy to Edward in exchange for homage.[2]

A consequence of this first war was to be the chronic insubordination of Flanders. After the count's surrender and imprisonment, it was left to the Flemish burghers to revolt against the French garrisons, and the French knights suffered a terrible defeat at Courtrai in July 1302. Thereafter the tide turned. But it was only in 1305 that a settlement satisfactory to the king could be reached.[1]

Aftermath

At a time when warfare was placing an unprecedented strain on royal resources, Gascony also supplied manpower. No English king, therefore, could afford to risk a French conquest of Gascony, for too much was at stake.[2]

The English Kings as Dukes of Aquitaine owed feudal allegiance to the French King and the conflicting claims of suzerainty and justice were a frequent source of disputes.[3] Given the inconveniences of the feudal relationship it may seem surprising that no wider conflict grew out of the Gascon situation before the 1330s. Yet until that decade the tensions arising from the English position in Gascony were contained and controlled.[2] The war marked a watershed in relations between the two powers.

References

- Encyclopædia Britannica, France – Foreign relations

- The Origins of the Hundred Years War, History Today, John Maddicott, Published in Volume: 36 Issue: 5, 1986

- Ginger M. Lee, "French War of 1294–1303", in Ronald H. Fritze and William Baxter Robison (eds.), Historical Dictionary of Late Medieval England, 1272–1485 (Greenwood, 2002), pp. 215–16 ISBN 9780313291241.