Anglophone problem

The Anglophone problem (French: Problème anglophone) in Cameroon refers to a socio-political issue rooted in the country's colonial legacies from the Germans, British, and the French.

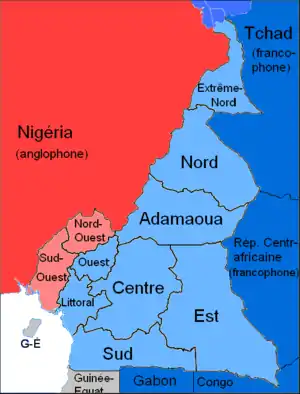

It principally goes against many Cameroonians from the Northwest and Southwest regions, who consider themselves Anglophones, to the Cameroonian government. These regions were formerly controlled by Britain (formally British Southern Cameroons) as a mandated and trust territory of the League of Nations and the United Nations. During the Foumban Conference of 1961, territories with different colonial legacies were finally united into one state.[1]

The issue is increasingly dominating national political agenda and has led to arguments and actions for federalism or separation from the union by Anglophones. Failure to address the problem threatens national unity.[2] The term "Anglophone" can be controversial, as many former French-speaking Cameroonians who are either multilingual or speak only English consider themselves Anglophones, despite the fact that some Northwesterners and Southwesterners do not believe there is an Anglophone problem.

Origins

European colonization

The origin can be traced back to World War I, when Cameroon was known as German Kamerun. Germans first gained influence in Cameroon in 1845 when Alfred Saker of the Baptist Missionary Society introduced a mission station.[3] In 1860, German merchants established a factory: the Woermann Company.[3] On 5 July 1884 local tribes provided the Woermann Company with rights to control the Kamerun River (the delta of the Wouri River),[4] consequently setting the foundation for the later German colonization of Kamerun.[3] In 1916, during World War I, France and Britain joined forces to conquer the colony.[3] Later, the Treaty of Versailles awarded France and Britain mandates over Cameroon as punishment for the Germans who lost the war. Most of German Kamerun was given to the French, over 430,000 km2 (167,000 sq mi),[3] while Britain was given Northern Cameroons, about 45,000 km2 (17,500 sq mi), and Southern Cameroons, 42,900 km2 (16,580 sq mi). Each colonizer would later influence the colonies with their European languages and cultures, creating Anglophones and Francophones in Cameroon. The large difference in awarded territory resulted in present-day Cameroon having a majority Francophone population and a minority Anglophone population.

Gaining independence

Following World War II, a wave of independence flowed rapidly throughout Africa. The United Nations forced Britain and France to relinquish their colonies and guide them towards independence. British Southern Cameroons had the political option to either unite with Nigeria or with French Cameroun, but none for self-determination through becoming independence was given. The most desired option was independence with the least popular being unification with French Cameroon.[5] However, during the British Plebiscite of 1961, the British argued that Southern Cameroons was not economically viable enough to sustain itself as an independent nation and could only survive by joining with Nigeria or La République du Cameroun (the Republic of Cameroon).[5] The United Nations rejected Southern Cameroons' appeal to have independence as a sovereign nation on the ballot. The plebiscite questions were:[5]

- Do you wish to achieve independence by joining the independent Federation of Nigeria?

- Do you wish to achieve independence by joining the independent Republic of Cameroun?

In February 1961, British Northern Cameroons voted to join Nigeria, while British Southern Cameroons voted to join La République du Cameroun.[1]

The Foumban Conference of 17–21 July 1961

The Foumban Constitutional Conference was held to create a constitution for the new Federal state of British Southern Cameroon and La République du Cameroun. The conference brought together representatives from La République du Cameroun, including President Amadou Ahidjo, and representatives from Southern Cameroons.[6] Two weeks before the Foumban Conference, there were reports that more than one hundred people were killed by terrorists in Loum, Bafang, Ndom, and Douala.[7] The reports worried unification advocates who wanted British Cameroon to unify with French Cameroun.[7] The location of Foumban had been carefully chosen to make Ahidjo appear as if he had everything under control. Mr. Mbile, a Southern Cameroonian representative at the conference, noted, "Free from all the unrest that had scared Southern Cameroonians, the Francophone authorities had picked the place deliberately for the occasion. The entire town had been exquisitely cleaned up and houses splashed with whitewash. Food was good and receptions lavish. The climate in Foumban real or artificial went far to convince us that despite the stories of 'murder and fire,' there could be at least this island of peace, east of the Mungo."[6]

Before the Foumban Conference, all parties in Southern Cameroons, the Native Authority Councils and traditional leaders attended the Bamenda Conference to decide on a common proposal to present during negotiations with La République du Cameroun. The Bamenda Conference agreed on a non-centralized federation to ensure a distinction between the powers of the states and the powers of the federation.[8] However, most of these proposals were ignored by Ahidjo.[8] Some of these proposals included having a bicameral legislature and decentralizing power, but instead a unicameral system was established with a centralized system of power.[6]

At the Foumban conference, Ahidjo presented delegates with a draft constitution. By the end of the conference, instead of creating an entirely new constitution, the contributions of the Southern Cameroons delegates were reflected in suggestions made to the draft initially presented to them.[8] John Ngu Foncha and Ahidjo intended for the conference to be brief; however, delegates left the three-day conference with the impression that there would be sequential conferences to continue drafting the constitution.[6][8] Mbile later noted, "We may have done more if we had spent five months instead of five days in writing our constitution at Foumban."[1] The Constitution for the new Federal Republic was agreed in Yaoundé in August 1961, between Ahidjo and Foncha, pending approval by the House of Assembly of the two states.[8] In the end, the West Cameroon House of Assembly never ratified the Constitution.[8] However, on 1 October 1961, the Federal Republic of Cameroon nevertheless came into existence.[8]

On 6 May 1972, Ahidjo announced his decision to convert the Federal Republic into a unitary state, provided that the idea was supported via referendum.[2] This suggestion violated articles in the Foumban document which stated that: 'any proposal for the revision of the present constitution, which impairs the unity and integrity of the Federation shall be inadmissible,' and 'proposals for revision shall be adopted by simple majority vote of the members of the Federal Assembly, provided that such majority includes a majority of the representatives ... of each of the Federated States,' not through referendum.[2] Despite these violations, the referendum passed, turning the Federal Republic into the United Republic of Cameroon.[2] In 1984, Ahidjo's successor, Paul Biya, replaced the name "United Republic of Cameroon" with "La République du Cameroun", the same name the francophone Cameroon had before federation talks.[9] With changes in the Constitution of 1996, reference to the existence of a territory called the British Southern Cameroons that had a "functioning self-government and recognized international boundaries" was essentially erased.[9] These actions suggest that the Francophone’s intentions may not have been to form a federal state, but rather to annex Southern Cameroons and not treat them as equals.[5]

Anglophone problem

Despite the non-acknowledgement/denial of the Anglophone problem from Francophone government leaders,[2] there exists a discontent by Anglophones, both young and old, as to how Anglophones are treated.[5] This discontent presents itself in calls for federation or separation with movements that are garnering strength.[5] At the core of Anglophone grievances is the loss of the former West Cameroon as a "distinct community defined by differences in official language and inherited colonial traditions of education, law, and public administration."[10] On 22 December 2016, in a letter to Paul Biya, the Anglophone Archbishops of Southern Cameroons define the Anglophone problem as follows:[5]

- The failure of successive governments of Cameroon, since 1961, to respect and implement the articles of the Constitution that uphold and safeguard what British Southern Cameroons brought along to the Union in 1961.[5]

- The flagrant disregard for the Constitution, demonstrated by the dissolution of political parties and the formation of one political party in 1966, the sacking of Jua and the appointment of Muna in 1968 as the Prime Minister of West Cameroon, and other such acts judged by West Cameroonians to be unconstitutional and undemocratic.[5]

- The cavalier management of the 1972 Referendum which took out the foundational element (Federalism) of the 1961 Constitution.[5]

- The 1984 Law amending the Constitution, which gave the country the original East Cameroon name (The Republic of Cameroon) and thereby erased the identity of the West Cameroonians from the original union. West Cameroon, which had entered the union as an equal partner, effectively ceased to exist.[5]

- The deliberate and systematic erosion of the West Cameroon cultural identity which the 1961 Constitution sought to preserve and protect by providing for a bi-cultural federation.[5]

Separation

Movements that advocate the separation of English-speaking Cameroon from French-speaking Cameroun exist, led by the Cameroon Action Group, the Southern Cameroons Youth League, the Southern Cameroons National Council, the Southern Cameroon Peoples Organization and the Ambazonia Movement.[5]

Federation

Advocates of Federation want a return to the constitution agreed upon in the 1961 Foumban Conference that acknowledges the history and culture of the two regions while giving equal power to the two.[5] This federation had been dismantled on 20 May 1972 by the larger French-speaking Cameroon and extended the latter's executive power throughout West Cameroon. Federation advocates include the instrumental Consortium of the leaders of three Cameroon-based trade unions: Lawyers, Teachers, and Transporters. It also includes some Cameroonians in the diaspora led by a well-organized US-based Anglophone Action Group, Inc. (AAG). AAG was one of the first groups in the diaspora to endorse the Cameroon-based Consortium as a peaceful alternative to achieving a return to the pre-1972 federated system. Opponents of federation include the ruling Cameroon Peoples Democratic Movement.

Struggle for political representation

In March 1990, the Social Democratic Front (SDF), led by John Fru Ndi, was founded on the perception of widespread Anglophone alienation. The SDF was the first major opposition party to the People's Democratic Movement, led by Paul Biya.[10]

Symptoms of Anglophone discontent

Below are various reasons that Anglophones feel marginalized, systemically, by the government.

- National entrance examinations into schools that develop the human resources of Cameroon are set by the French system of education. This makes it difficult for Anglophones and Francophones to compete on an equal playing field. The Examination Board members are all Francophone, which places some bias against Anglophone candidates.[5]

- There are five ministries that concern education and none of them are Anglophone.[5]

- Of the 36 ministers who defended the budgets for the ministries last month, only one was Anglophone.[5]

- In the 1961 Constitution, the Vice President was the second most important person in state protocol. Today, the prime minister (an appointed Anglophone) is the fourth most important person in state protocol, after the president of the Senate and the president of the National Assembly.[5]

Prioritization of French over English

- State institutions publish documents and public notices in French only, without English translations.[5]

- National entrance examinations into some professional schools are set in French only, sometimes even in English-speaking regions.[5]

- Most heads of government offices speak only French, even in English-speaking regions. Visitors and clients to government offices are then expected to speak in French.[5]

- Most senior administrators and members of the forces of law and order in the Northwest and Southwest Regions are French-speaking and there is no effort made to require them to demonstrate an understanding of Anglophone culture.[5]

- Members of inspection teams, missions, and facilitators for seminars sent from the Ministries in Yaoundé to Southern Cameroon are mostly French-speaking, and English-speaking audiences are expected to understand them.[5]

- Most of the military tribunals in the Northwest and Southwest Regions conduct their courts in French.[5]

- Finance documents such as the COBAC Code, the CIMA Code and the OHADA Code are all in French.[5]

- Magistrates in the Southern Cameroon regions are disproportionately Francophone. In addition, other government-appointed officials are disproportionately Francophone. There are Francophone principals in Anglophone schools, and hospitals, banks and mobile telephone companies are predominantly Francophone.[5]

Spiraling

As of 2023, the Anglophone problem is still on-going. It has spiralled into violence with police officers and gendarmes shooting dead several civilians. Official sources have put the number at 17 dead, but local individuals and groups have talked of 50 or more.[11] Radical members of some secessionist groups have killed several police officers and gendarmes.[12] 15,000 refugees have fled Southern Cameroons into neighbouring Nigeria, with the UNHCR expecting that number to grow to 40,000 if the situation continues.[13]

Outcomes

Without clearly acknowledging the existence of the Anglophone problem, the President Paul Biya has attempted to appease tensions by making a number of announcements:

- He ordered the creation of a Common Law department at the Supreme Court and the School of Administration and Magistracy, ENAM.[14]

- In his 2017 traditional end-of-year address, he announced that there would be an effective decentralization scheme implemented by the government.[15] The issue of decentralization is one of the major tenets of Cameroon's 1996 constitution which was spearheaded by Anglophone opposition groups in parliament.

Several separatist or secessionist groups have emerged or become more prominent as a result of the harsh response by the government to the Anglophone problem. These groups desire to see Southern Cameroons completely separate from La République du Cameroun and form its own state, sometimes referred to as Ambazonia. Some groups such as the Southern Cameroons Ambazonia Consortium United Front (SCACUF) have used diplomatic means in an attempt to gain independence for the Anglophone regions,[16] whereas other groups began to employ armed confrontation with artisan weapons against the deployed gendarmes and soldiers in those regions.

See also

References

- Ndi, Anthony (2014). Southern West Cameroon Revisited (1950-1972): Unveiling Inescapable Traps. Langaa RPCIG.

- Konings, Piet (1997). "The Anglophone Problem in Cameroon". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 35 (2): 207–229. doi:10.1017/S0022278X97002401. hdl:1887/4616. S2CID 145801145.

- Olson, James (1996). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Greenwood Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-313-27917-9.

- "German Cameroon", Wikipedia, 2019-08-30, retrieved 2019-10-20

- Anglophone Archbishops (December 22, 2016). "Bamenda Provincial Episcopal Conference [BAPEC]". newspaper.

- Konings, Piet (2003). Negotiating an Anglophone Identity: A study of the politics of recognition and representation in Cameroon. Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 9004132953.

- Dounge, Germanus (January 18, 2017). "The Legal Argument for Southern Cameroon Independence". www.africafederation.net.

- Atanga, Mufor (2011). The Anglophone Cameroon Predicament. Bamenda: Langaa Research & Publishing CIG. ISBN 978-9956717118.

- Achankeng, Fonkem (2014). "The Foumban "Constitutional" Talks and Prior Intentions of Negotiating: A Historico-Theoretical Analysis of a False Negotiation and the Ramications for Political Developments in Cameroon". Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective. 9: 149.

- Eyoh, Dickson (1998). "Conflicting Narratives of Anglophone Protest and the Politics of Identity in Cameroon". Journal of Contemporary African Studies. 16 (2): 249–276. doi:10.1080/02589009808729630.

- AfricaNews. "Cameroon's Anglophone crisis resulted in 17 deaths - Amnesty | Africanews". Africanews. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- AfricaNews. "Four soldiers killed in Cameroon's Anglophone region | Africanews". Africanews. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- Dahir, Abdi Latif. "Cameroon's Anglophone crisis is threatening to spin out of control". Quartz. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- "Biya Orders Creation Of Common Law Depts At Supreme Court, ENAM | CameroonPostline". www.cameroonpostline.com. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- "President Paul BIYA to the Nation". www.prc.cm. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- "Click To Learn More About The Interim Government of Ambazonia - AmbaGov". ambagov.org. Retrieved 2018-01-15.