European eel

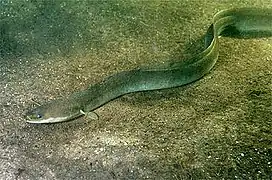

The European eel (Anguilla anguilla)[3] is a species of eel, a snake-like, catadromous fish. They are normally around 60–80 cm (2.0–2.6 ft) and rarely reach more than 1 m (3 ft 3 in), but can reach a length of up to 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) in exceptional cases.

| European eel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Anguilliformes |

| Family: | Anguillidae |

| Genus: | Anguilla |

| Species: | A. anguilla |

| Binomial name | |

| Anguilla anguilla | |

| |

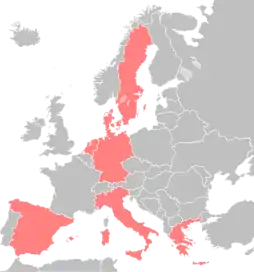

| Freshwater range of wild European eel | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Muraena anguilla Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Eels have been important sources of food both as adults (including jellied eels of East London) and as glass eels. Glass-eel fishing using basket traps has been of significant economic value in many river estuaries on the western seaboard of Europe.

While the species' lifespan in the wild has not been determined, captive specimens have lived over 80 years. A specimen known as "the Brantevik Eel" lived for 155 years in the well of a family home in Brantevik, a fishing village in southern Sweden.[4][5][6]

Conservation status

The European eel is a critically endangered species.[1] Since the 1970s, the numbers of eels reaching Europe is thought to have declined by around 90% (possibly even 98%). Contributing factors include overfishing, parasites such as Anguillicola crassus, barriers to migration such as hydroelectric dams, and natural changes in the North Atlantic oscillation, Gulf Stream, and North Atlantic drift. Recent work suggests polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) pollution may be a factor in the decline.[7] TRAFFIC is introducing traceability and legality systems throughout trade change to control the decline and encourage a U-turn on the species.[8] The species is listed in Appendix II of the CITES Convention.[9]

Sustainable consumption

In 2010, Greenpeace International added the European eel to its "seafood red list",[10] and the Sustainable Eel Group launched the Sustainable Eel Standard.[11]

Breeding projects

As the European eel population has been falling for some time, several projects have been started. In 1997, Innovatie Netwerk in the Netherlands initiated a project where they attempted to get European eels to breed in captivity by simulating the 6,500 km (4,000 mi) journey from Europe to the Sargasso Sea with a swimming machine for the fish.[12][13]

The first to achieve some success was DTU Aqua, a part of the Technical University of Denmark. Through a combination of fresh and salt water, as well as hormones, they were able to breed it in captivity in 2006 and make the larvae survive for 4.5 days after hatching.[14] By 2007, DTU Aqua scientists were able to set a new record where the larvae survived for 12 days by feeding the mother eel with a special arginine-enriched diet.[15] At this age the content of the larval yolk sac has been used, the mouth and digestive channel have developed, and it requires feeding. Attempts with various substances failed.[16] Deep water sampling of the presumed habitat of larval European eel in the Sargasso Sea was performed by the Galathea 3 expedition in 2006–07, in the hope of revealing the likely feeding preference at the early stage. Their results indicated that they feed on various planktonic organisms, but especially microscopic jellyfish.[16] A follow-up expedition was performed by DTU's own research ship to the Sargasso Sea region in 2014.[17]

To further the research, the PRO-EEL project, led by DTU Aqua and involving several research institutes elsewhere in Denmark (University of Copenhagen and others), Norway (Norwegian Institute of Fisheries and Food Research and others), the Netherlands (Leiden University and others), Belgium (Ghent University), France (French National Center for Scientific Research and others), Spain (ICTA at Polytechnic University of Valencia) and Tunisia (National Institute of Marine Sciences and Technologies), was started in 2010.[18][19] By 2014, the eel larvae at their facilities typically survived 20–22 days,[20] and by 2022 they were surviving up to around 140 days, well into the leptocephalus stage (the stage just before glass eel), but the full life cycle has still not been completed in captivity.[21]

Life history

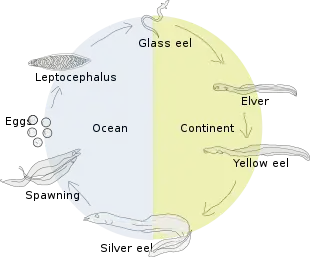

Much of the European eel's life history was a mystery for centuries, as fishermen never caught anything they could identify as a young eel. Unlike many other migrating fish, eels begin their life cycle in the ocean and spend most of their lives in fresh inland water, or brackish coastal water, returning to the ocean to spawn and then die. In the early 1900s, Danish researcher Johannes Schmidt identified the Sargasso Sea as the most likely spawning grounds for European eels.[22] The larvae (leptocephali) drift towards Europe in a 300-day migration.[23]

When approaching the European coast, the larvae metamorphose into a transparent larval stage called "glass eel", enter estuaries, and many start migrating upstream. After entering their continental habitat, the glass eels metamorphose into elvers, miniature versions of the adult eels. As the eel grows, it becomes known as a "yellow eel" due to the brownish-yellow color of their sides and belly. After 5–20 years in fresh or brackish water, the eels become sexually mature, their eyes grow larger, their flanks become silver, and their bellies white in color. In this stage, the eels are known as "silver eels", and they begin their migration back to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. Silvering is important in an eel's development because it allows for increased levels of the steroid hormone cortisol, which is needed for their migration from fresh water back to the sea.[24] Cortisol plays a role in the long migration because it allows for the mobilization of energy during migration.[25] Also playing a key role in silvering is the production of the steroid 11-Ketotestosterone (11-KT), which prepares the eel for structural changes to the skin to endure the migration from fresh water to saltwater.[26]

Magnetoreception has also been reported in the European eel by at least one study, and may be used for navigation.[27]

Life cycle of the European eel

Life cycle of the European eel Glass eels at the transition from ocean to fresh water

Glass eels at the transition from ocean to fresh water Mature silver-stage European eels migrate back to the ocean

Mature silver-stage European eels migrate back to the ocean

Ecology

Parasites

Parasite species infecting the European eel include Bothriocephalus claviceps[28] and a range of other intestinal metazoans.[29]

European eels generally have a low parasite diversity within individuals and ecosystems (component community). The parasite that is most commonly dominant is the acanthocephalan Acanthocephalus lucii.[29]

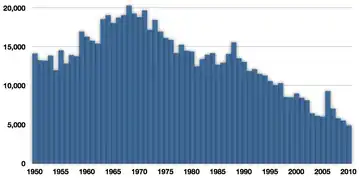

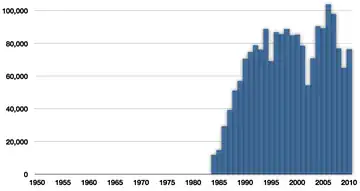

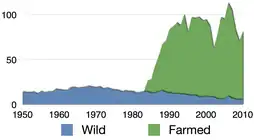

Commercial fisheries

References

- Pike, C.; Crook, V.; Gollock, M. (2020). "Anguilla anguilla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T60344A152845178. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T60344A152845178.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- "Anguilla anguilla". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 11 March 2006.

- "World's oldest eel dies in Swedish well". The Local. 8 August 2014.

- "Anguilla anguilla (Linnaeus, 1758) European eel". FishBase. fishbase.org. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Deelder, C. L. (1984). "Synopsis of Biological Data On the Eel Anguilla anguilla (Linnaeus, 1758)" (PDF). www.fao.org. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. p. 12. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- "PCBs are killing off eels". New Scientist. 2452: 6. 2006.

- "Other Aquatic species – Species we work with at TRAFFIC". www.traffic.org. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- "CITES Appendix listings". www.cites.org. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- Greenpeace International Seafood Red list Archived 10 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Sustainable Eel Standard

- EOAS magazine, september 2010

- Innofisk Volendam breedign project

- Ritzau (6 July 2006). Danske forskere får ål til at yngle udenfor Sargassohavet. Politiken. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Nywold, M. (5 October 2007). Dansk forskergennembrud kan sikre ålens overlevelse. Ingeniøren. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Galathea 3: Åleopdræt. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- DTU (6 November 2014). Danish Eel Expedition 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- PRO-EEL: Partners. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Wageningen University and Research: PRO-EEL: Reproduction of the European eel: Towards a self-sustaining aquaculture. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Borup, A.T. (13 December 2014). Ålens kode skal knækkes i Hirtshals. Archived 22 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Nordjyske. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Politis, S.N.; Sørensen, S.R.; Conceicao, L.; Santos, A.; Benini, E.; Bandara, K.; Sganga, D.; Branco, J.; Tomkiewicz, J. (30 September 2022). "European eel larviculture: First establishment of feeding Leptocephalus culture". Aquaeas. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- Schmidt, Johs. (1912). "Danish Researches in the Atlantic and Mediterranean on the Life‐History of the Freshwater‐Eel (Anguilla vulgaris, Turt.). With notes on other species.) with Plates IV—IX and 2 Text‐figures". Internationale Revue der Gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie. 5 (2–3): 317–342. doi:10.1002/iroh.19120050207.

- "FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture Anguilla anguilla". Fao.org. 1 January 2004. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- Balm, S. Paul; Durif, Caroline; van Ginneken, Vincent; Antonissen, Erik; Boot, Ron; van Den Thillart, Guido; Verstegen, Martin (2007). "Silvering of European eel (Anguilla anguilla L.): seasonal changes of morphological and metabolic parameters". Animal Biology. 57 (1): 63–77. doi:10.1163/157075607780002014. ISSN 1570-7555.

- Dufour, Sylvie; Ginneken, Vincent van; Durif, Caroline; Doornbos, Jorg; Noorlander, Kees; Thillart, Guido van den; Boot, Ron; Murk, Albertinka; Sbaihi, Miskal (1 January 2007). "Endocrine profiles during silvering of the European eel (Anguilla anguilla L.) living in saltwater". Animal Biology. 57 (4): 453–465. doi:10.1163/157075607782232143. ISSN 1570-7563.

- Lokman, P. Mark; Vermeulen, Gerard J.; Lambert, Jan G.D.; Young, Graham (1 December 1998). "Gonad histology and plasma steroid profiles in wild New Zealand freshwater eels (Anguilla dieffenbachii and A. australis) before and at the onset of the natural spawning migration. I. Females*". Fish Physiology and Biochemistry. 19 (4): 325–338. doi:10.1023/A:1007719414295. ISSN 1573-5168. S2CID 24194486.

- "Eels May Use 'Magnetic Maps' As They Slither Across The Ocean". NPR. 13 April 2017.

- Scholz, T. (1997). "Life-cycle of Bothriocephalus claviceps , a specific parasite of eels". Journal of Helminthology. 71 (3): 241–248. doi:10.1017/S0022149X00015984. PMID 9271472. S2CID 5700982.

- Kennedy, C. R.; Hartvigsen, R. A. (2000). "Richness and diversity of intestinal metazoan communities in brown trout Salmo trutta compared to those of eels Anguilla anguilla in their European heartlands". Parasitology. 121 (1): 55–64. doi:10.1017/S0031182099006046. PMID 11085225. S2CID 9974499.

- Based on data sourced from the FishStat database Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, FAO.

External links

Media related to Anguilla anguilla at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Anguilla anguilla at Wikimedia Commons