Jerk (physics)

In physics, jerk (also known as jolt) is the rate of change of an object's acceleration over time. It is a vector quantity (having both magnitude and direction). Jerk is most commonly denoted by the symbol j and expressed in m/s3 (SI units) or standard gravities per second (g0/s).

| Jerk | |

|---|---|

Time-derivatives of position, including jerk | |

Common symbols | j, j, ȷ→ |

| In SI base units | m/s3 |

| Dimension | L T−3 |

Expressions

As a vector, jerk j can be expressed as the first time derivative of acceleration, second time derivative of velocity, and third time derivative of position:

Where:

- a is acceleration

- v is velocity

- r is position

- t is time

Third-order differential equations of the form

are sometimes called jerk equations. When converted to an equivalent system of three ordinary first-order non-linear differential equations, jerk equations are the minimal setting for solutions showing chaotic behaviour. This condition generates mathematical interest in jerk systems. Systems involving fourth-order derivatives or higher are accordingly called hyperjerk systems.[1]

Physiological effects and human perception

Human body position is controlled by balancing the forces of antagonistic muscles. In balancing a given force, such as holding up a weight, the postcentral gyrus establishes a control loop to achieve the desired equilibrium. If the force changes too quickly, the muscles cannot relax or tense fast enough and overshoot in either direction, causing a temporary loss of control. The reaction time for responding to changes in force depends on physiological limitations and the attention level of the brain: an expected change will be stabilized faster than a sudden decrease or increase of load.

To avoid vehicle passengers losing control over body motion and getting injured, it is necessary to limit the exposure to both the maximum force (acceleration) and maximum jerk, since time is needed to adjust muscle tension and adapt to even limited stress changes. Sudden changes in acceleration can cause injuries such as whiplash.[2] Excessive jerk may also result in an uncomfortable ride, even at levels that do not cause injury. Engineers expend considerable design effort minimizing "jerky motion" on elevators, trams, and other conveyances.

For example, consider the effects of acceleration and jerk when riding in a car:

- Skilled and experienced drivers can accelerate smoothly, but beginners often provide a jerky ride. When changing gears in a car with a foot-operated clutch, the accelerating force is limited by engine power, but an inexperienced driver can cause severe jerk because of intermittent force closure over the clutch.

- The feeling of being pressed into the seats in a high-powered sports car is due to the acceleration. As the car launches from rest, there is a large positive jerk as its acceleration rapidly increases. After the launch, there is a small, sustained negative jerk as the force of air resistance increases with the car's velocity, gradually decreasing acceleration and reducing the force pressing the passenger into the seat. When the car reaches its top speed, the acceleration has reached 0 and remains constant, after which there is no jerk until the driver decelerates or changes direction.

- When braking suddenly or during collisions, passengers whip forward with an initial acceleration that is larger than during the rest of the braking process because muscle tension regains control of the body quickly after the onset of braking or impact. These effects are not modeled in vehicle testing because cadavers and crash test dummies do not have active muscle control.

- To minimize the effects of a jerk, curves along roads are designed to be clothoids as are railroad curves and roller coaster loops.

Force, acceleration, and jerk

For a constant mass m, acceleration a is directly proportional to force F according to Newton's second law of motion:

In classical mechanics of rigid bodies, there are no forces associated with the derivatives of acceleration; however, physical systems experience oscillations and deformations as a result of jerk. In designing the Hubble Space Telescope, NASA set limits on both jerk and jounce.[3]

The Abraham–Lorentz force is the recoil force on an accelerating charged particle emitting radiation. This force is proportional to the particle's jerk and to the square of its charge. The Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory is a more advanced theory, applicable in a relativistic and quantum environment, and accounting for self-energy.

In an idealized setting

Discontinuities in acceleration do not occur in real-world environments because of deformation, quantum mechanics effects, and other causes. However, a jump-discontinuity in acceleration and, accordingly, unbounded jerk are feasible in an idealized setting, such as an idealized point mass moving along a piecewise smooth, whole continuous path. The jump-discontinuity occurs at points where the path is not smooth. Extrapolating from these idealized settings, one can qualitatively describe, explain and predict the effects of jerk in real situations.

Jump-discontinuity in acceleration can be modeled using a Dirac delta function in jerk, scaled to the height of the jump. Integrating jerk over time across the Dirac delta yields the jump-discontinuity.

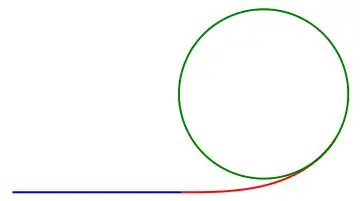

For example, consider a path along an arc of radius r, which tangentially connects to a straight line. The whole path is continuous, and its pieces are smooth. Now assume a point particle moves with constant speed along this path, so its tangential acceleration is zero. The centripetal acceleration given by v2/r is normal to the arc and inward. When the particle passes the connection of pieces, it experiences a jump-discontinuity in acceleration given by v2/r, and it undergoes a jerk that can be modeled by a Dirac delta, scaled to the jump-discontinuity.

For a more tangible example of discontinuous acceleration, consider an ideal spring–mass system with the mass oscillating on an idealized surface with friction. The force on the mass is equal to the vector sum of the spring force and the kinetic frictional force. When the velocity changes sign (at the maximum and minimum displacements), the magnitude of the force on the mass changes by twice the magnitude of the frictional force, because the spring force is continuous and the frictional force reverses direction with velocity. The jump in acceleration equals the force on the mass divided by the mass. That is, each time the mass passes through a minimum or maximum displacement, the mass experiences a discontinuous acceleration, and the jerk contains a Dirac delta until the mass stops. The static friction force adapts to the residual spring force, establishing equilibrium with zero net force and zero velocity.

Consider the example of a braking and decelerating car. The brake pads generate kinetic frictional forces and constant braking torques on the disks (or drums) of the wheels. Rotational velocity decreases linearly to zero with constant angular deceleration. The frictional force, torque, and car deceleration suddenly reach zero, which indicates a Dirac delta in physical jerk. The Dirac delta is smoothed down by the real environment, the cumulative effects of which are analogous to damping of the physiologically perceived jerk. This example neglects the effects of tire sliding, suspension dipping, real deflection of all ideally rigid mechanisms, etc.

Another example of significant jerk, analogous to the first example, is the cutting of a rope with a particle on its end. Assume the particle is oscillating in a circular path with non-zero centripetal acceleration. When the rope is cut, the particle's path changes abruptly to a straight path, and the force in the inward direction changes suddenly to zero. Imagine a monomolecular fiber cut by a laser; the particle would experience very high rates of jerk because of the extremely short cutting time.

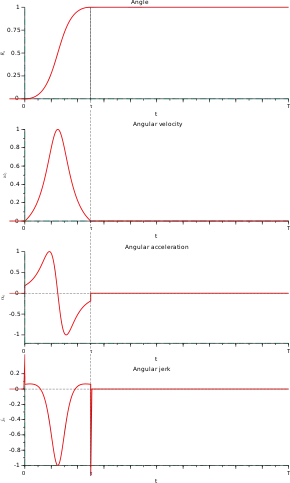

In rotation

Consider a rigid body rotating about a fixed axis in an inertial reference frame. If its angular position as a function of time is θ(t), the angular velocity, acceleration, and jerk can be expressed as follows:

- Angular velocity, , is the time derivative of θ(t).

- Angular acceleration, , is the time derivative of ω(t).

- Angular jerk, , is the time derivative of α(t).

Angular acceleration equals the torque acting on the body, divided by the body's moment of inertia with respect to the momentary axis of rotation. A change in torque results in angular jerk.

The general case of a rotating rigid body can be modeled using kinematic screw theory, which includes one axial vector, angular velocity Ω(t), and one polar vector, linear velocity v(t). From this, the angular acceleration is defined as

and the angular jerk is given by

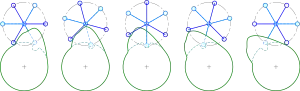

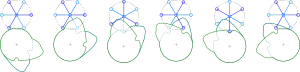

For example, consider a Geneva drive, a device used for creating intermittent rotation of a driven wheel (the blue wheel in the animation) by continuous rotation of a driving wheel (the red wheel in the animation). During one cycle of the driving wheel, the driven wheel's angular position θ changes by 90 degrees and then remains constant. Because of the finite thickness of the driving wheel's fork (the slot for the driving pin), this device generates a discontinuity in the angular acceleration α, and an unbounded angular jerk ζ in the driven wheel.

Jerk does not preclude the Geneva drive from being used in applications such as movie projectors and cams. In movie projectors, the film advances frame-by-frame, but the projector operation has low noise and is highly reliable because of the low film load (only a small section of film weighing a few grams is driven), the moderate speed (2.4 m/s), and the low friction.

With cam drive systems, use of a dual cam can avoid the jerk of a single cam; however, the dual cam is bulkier and more expensive. The dual-cam system has two cams on one axle that shifts a second axle by a fraction of a revolution. The graphic shows step drives of one-sixth and one-third rotation per one revolution of the driving axle. There is no radial clearance because two arms of the stepped wheel are always in contact with the double cam. Generally, combined contacts may be used to avoid the jerk (and wear and noise) associated with a single follower (such as a single follower gliding along a slot and changing its contact point from one side of the slot to the other can be avoided by using two followers sliding along the same slot, one side each).

In elastically deformable matter

An elastically deformable mass deforms under an applied force (or acceleration); the deformation is a function of its stiffness and the magnitude of the force. If the change in force is slow, the jerk is small, and the propagation of deformation is considered instantaneous as compared to the change in acceleration. The distorted body acts as if it were in a quasistatic regime, and only a changing force (nonzero jerk) can cause propagation of mechanical waves (or electromagnetic waves for a charged particle); therefore, for nonzero to high jerk, a shock wave and its propagation through the body should be considered.

The propagation of deformation is shown in the graphic "Compression wave patterns" as a compressional plane wave through an elastically deformable material. Also shown, for angular jerk, are the deformation waves propagating in a circular pattern, which causes shear stress and possibly other modes of vibration. The reflection of waves along the boundaries cause constructive interference patterns (not pictured), producing stresses that may exceed the material's limits. The deformation waves may cause vibrations, which can lead to noise, wear, and failure, especially in cases of resonance.

The graphic captioned "Pole with massive top" shows a block connected to an elastic pole and a massive top. The pole bends when the block accelerates, and when the acceleration stops, the top will oscillate (damped) under the regime of pole stiffness. One could argue that a greater (periodic) jerk might excite a larger amplitude of oscillation because small oscillations are damped before reinforcement by a shock wave. One can also argue that a larger jerk might increase the probability of exciting a resonant mode because the larger wave components of the shock wave have higher frequencies and Fourier coefficients.

To reduce the amplitude of excited stress waves and vibrations, one can limit jerk by shaping motion and making the acceleration continuous with slopes as flat as possible. Due to limitations of abstract models, algorithms for reducing vibrations include higher derivatives, such as jounce, or suggest continuous regimes for both acceleration and jerk. One concept for limiting jerk is to shape acceleration and deceleration sinusoidally with zero acceleration in between (see graphic captioned "Sinusoidal acceleration profile"), making the speed appear sinusoidal with constant maximum speed. The jerk, however, will remain discontinuous at the points where acceleration enters and leaves the zero phases.

In the geometric design of roads and tracks

Roads and tracks are designed to limit the jerk caused by changes in their curvature. On railways, designers use 0.35 m/s3 as a design goal and 0.5 m/s3 as a maximum. Track transition curves limit the jerk when transitioning from a straight line to a curve, or vice versa. Recall that in constant-speed motion along an arc, acceleration is zero in the tangential direction and nonzero in the inward normal direction. Transition curves gradually increase the curvature and, consequently, the centripetal acceleration.

An Euler spiral, the theoretically optimum transition curve, linearly increases centripetal acceleration and results in constant jerk (see graphic). In real-world applications, the plane of the track is inclined (cant) along the curved sections. The incline causes vertical acceleration, which is a design consideration for wear on the track and embankment. The Wiener Kurve (Viennese Curve) is a patented curve designed to minimize this wear.[4][5]

Rollercoasters[2] are also designed with track transitions to limit jerk. When entering a loop, acceleration values can reach around 4g (40 m/s2), and riding in this high acceleration environment is only possible with track transitions. S-shaped curves, such as figure eights, also use track transitions for smooth rides.

In motion control

In motion control, the design focus is on straight, linear motion, with the need to move a system from one steady position to another (point-to-point motion). The design concern from a jerk perspective is vertical jerk; the jerk from tangential acceleration is effectively zero since linear motion is non-rotational.

Motion control applications include passenger elevators and machining tools. Limiting vertical jerk is considered essential for elevator riding convenience.[6] ISO 18738[7] specifies measurement methods for elevator ride quality with respect to jerk, acceleration, vibration, and noise; however, the standard does not specify levels for acceptable or unacceptable ride quality. It is reported[8] that most passengers rate a vertical jerk of 2 m/s3 as acceptable and 6 m/s3 as intolerable. For hospitals, 0.7 m/s3 is the recommended limit.

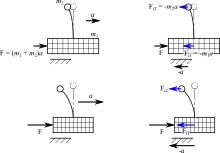

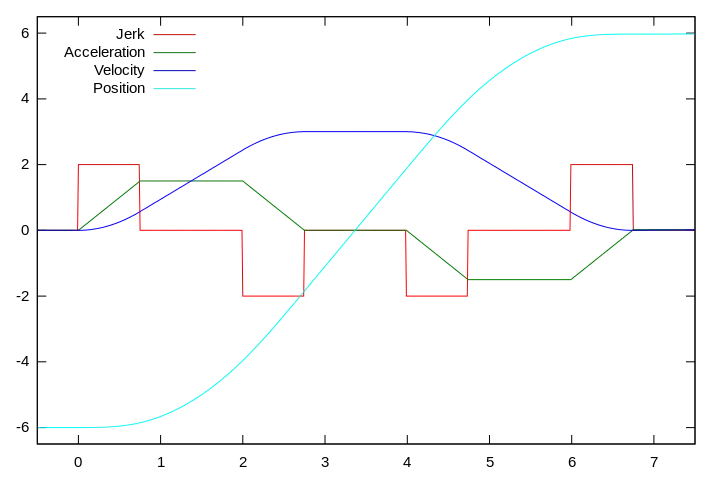

A primary design goal for motion control is to minimize the transition time without exceeding speed, acceleration, or jerk limits. Consider a third-order motion-control profile with quadratic ramping and deramping phases in velocity (see figure).

This motion profile consists of the following seven segments:

- Acceleration build up — positive jerk limit; linear increase in acceleration to the positive acceleration limit; quadratic increase in velocity

- Upper acceleration limit — zero jerk; linear increase in velocity

- Acceleration ramp down — negative jerk limit; linear decrease in acceleration; (negative) quadratic increase in velocity, approaching the desired velocity limit

- Velocity limit — zero jerk; zero acceleration

- Deceleration build up — negative jerk limit; linear decrease in acceleration to the negative acceleration limit; (negative) quadratic decrease in velocity

- Lower deceleration limit — zero jerk; linear decrease in velocity

- Deceleration ramp down — positive jerk limit; linear increase in acceleration to zero; quadratic decrease in velocity; approaching the desired position at zero speed and zero acceleration

Segment four's time period (constant velocity) varies with distance between the two positions. If this distance is so small that omitting segment four would not suffice, then segments two and six (constant acceleration) could be equally reduced, and the constant velocity limit would not be reached. If this modification does not sufficiently reduce the crossed distance, then segments one, three, five, and seven could be shortened by an equal amount, and the constant acceleration limits would not be reached.

Other motion profile strategies are used, such as minimizing the square of jerk for a given transition time[9] and, as discussed above, sinusoidal-shaped acceleration profiles. Motion profiles are tailored for specific applications including machines, people movers, chain hoists, automobiles, and robotics.

In manufacturing

Jerk is an important consideration in manufacturing processes. Rapid changes in acceleration of a cutting tool can lead to premature tool wear and result in uneven cuts; consequently, modern motion controllers include jerk limitation features. In mechanical engineering, jerk, in addition to velocity and acceleration, is considered in the development of cam profiles because of tribological implications and the ability of the actuated body to follow the cam profile without chatter.[10] Jerk is often considered when vibration is a concern. A device that measures jerk is called a "jerkmeter".

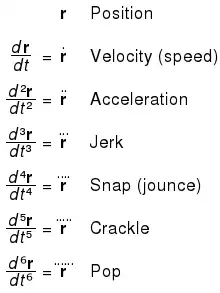

Further derivatives

Further time derivatives have also been named, as snap or jounce (fourth derivative), crackle (fifth derivative), and pop (sixth derivative).[11][12] However, time derivatives of position of higher order than four appear rarely.[13]

The terms snap, crackle, and pop—for the fourth, fifth, and sixth derivatives of position—were inspired by the advertising mascots Snap, Crackle, and Pop.[12]

See also

References

- Chlouverakis, Konstantinos E.; Sprott, J. C. (2006). "Chaotic hyperjerk systems" (PDF). Chaos, Solitons & Fractals. 28 (3): 739–746. Bibcode:2006CSF....28..739C. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2005.08.019.

- "How Things Work: Roller Coasters - The Tartan Online". Thetartan.org. 2007-04-16. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- "Third derivative of position". math.ucr.edu. Retrieved 2019-09-08.

- https://depatisnet.dpma.de/DepatisNet/depatisnet?window=1&space=menu&content=treffer&action=pdf&docid=AT000000412975B

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-13. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ISO 18738-1:2012. "Measurement of ride quality -- Part 1: Lifts (elevators)". International Organization for Standardization. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- Howkins, Roger E. "Elevator Ride Quality - The Human Ride Experience". VFZ-Verlag für Zielgruppeninformationen GmbH & Co. KG. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- Hogan, Neville (1984). "An organizing principle for a class of voluntary movements". J. Neurosci. 4 (11): 2745–2754. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-11-02745.1984. PMC 6564718. PMID 6502203.

- Blair, G., "Making the Cam", Race Engine Technology 10, September–October 2005

- Thompson, Peter M. (March 2011). "Snap, Crackle, and Pop" (PDF). Proc of AIAA Southern California Aerospace Systems and Technology Conference. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-04. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

The common names for the first three derivatives are velocity, acceleration, and jerk. The not so common names for the next three derivatives are snap, crackle, and pop.

- Visser, Matt (31 March 2004). "Jerk, snap and the cosmological equation of state". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 21 (11): 2603–2616. arXiv:gr-qc/0309109. Bibcode:2004CQGra..21.2603V. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/21/11/006. ISSN 0264-9381. S2CID 10468158.

Snap [the fourth time derivative] is also sometimes called jounce. The fifth and sixth time derivatives are sometimes somewhat facetiously referred to as crackle and pop.

- Gragert, Stephanie; Gibbs, Philip (November 1998). "What is the term used for the third derivative of position?". Usenet Physics and Relativity FAQ. Math Dept., University of California, Riverside. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- Sprott JC (2003). Chaos and Time-Series Analysis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850839-5.

- Sprott JC (1997). "Some simple chaotic jerk functions" (PDF). Am J Phys. 65 (6): 537–43. Bibcode:1997AmJPh..65..537S. doi:10.1119/1.18585. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2009-09-28.

- Blair G (2005). "Making the Cam" (PDF). Race Engine Technology (10). Retrieved 2009-09-29.