Anne Seymour, Duchess of Somerset

Anne Seymour, Duchess of Somerset (née Stanhope; before 1512 – 16 April 1587) was the second wife of Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (c. 1500–1552), who held the office of Lord Protector during the first part of the reign of their nephew King Edward VI. The Duchess was briefly the most powerful woman in England. During her husband's regency she unsuccessfully claimed precedence over the queen dowager, Catherine Parr.

Anne Seymour | |

|---|---|

| Duchess of Somerset | |

| |

| Born | c. 1510 |

| Died | 16 April 1587 Hanworth Palace, Middlesex |

| Buried | Westminster Abbey, London |

| Spouse(s) | Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset Francis Newdigate |

| Issue | Edward Seymour Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford Anne Dudley, Countess of Warwick Lady Jane Seymour Mary Seymour Elizabeth Seymour Lord Henry Seymour |

| Father | Sir Edward Stanhope |

| Mother | Elizabeth Bourchier |

Family

Anne Stanhope was likely born in 1510, the only child of Sir Edward Stanhope (1462 – 6 June 1511) by his wife Elizabeth Bourchier (b. before 1473, d. 1557),[1] a daughter of Fulk Bourchier, 10th Baron FitzWarin (1445–1479). By her father's first marriage to Adelina Clifton she had two half-brothers, Richard Stanhope (died 1529) and Sir Michael Stanhope.[2] After the death of Sir Edward Stanhope in 1511, his widow, Elizabeth, married Sir Richard Page of Beechwood, Hertfordshire.[3]

Her paternal grandparents were Thomas Stanhope, esquire, of Shelford and Margaret (or Mary) Jerningham,[4] and her maternal grandparents were Fulke Bourchier, 2nd Baron Fitzwaryn and Elizabeth Dynham. Through her mother, Anne was a descendant of Thomas of Woodstock, the youngest son of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault.[5]

Anne's snobbery and pride were considered to be intolerable, yet she was highly intelligent and determined.[6] Antonio de Guaras, a Spanish merchant living in London, would later say of her, that she was "more presumptuous than Lucifer".[7]

First marriage

Anne Stanhope married Sir Edward Seymour sometime before 9 March 1535. Seymour's first marriage, to Catherine Fillol, had possibly been annulled, but his first wife was probably dead by then. Edward Seymour was the eldest brother of Jane Seymour, the third wife of Henry VIII. Shortly after the king's marriage to Jane in June 1536, Edward Seymour was elevated to the peerage as Viscount Beauchamp. In October 1537, after the birth of his royal nephew Edward, he was created Earl of Hertford. In 1547, he became a duke, so Anne became the Duchess of Somerset.

Issue

Anne had ten children by Edward Seymour:

- Edward Seymour, Viscount Beauchamp of Hache (12 October 1537 – 1539)

- Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford (second creation of that title) (22 May 1539 – 1621), married firstly in November 1560, Lady Catherine Grey, by whom he had two sons; he married secondly in 1582, Frances Howard; and thirdly in 1601, Frances Prannell (born Lady Frances Howard), widow of Henry Prannell.

- Lord Henry Seymour (1540–?) married Lady Joan Percy, daughter of Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of Northumberland

- Lady Anne Seymour (1538–1588), married firstly John Dudley, 2nd Earl of Warwick; she married secondly Sir Edward Unton, MP, by whom she had issue.

- Lady Margaret Seymour (1540 – ?) noted Elizabethan author

- Lady Jane Seymour (1541–1561) Maid of Honour to Queen Elizabeth I, noted Elizabethan author

- Lady Catherine Seymour (1548–1625)

- Lord Edward Seymour (1548–1574), unmarried and without issue

- Lady Mary Seymour (born 1552, buried 18 January 1620 Westminster Abbey) married three times (Andrew Rogers, of Bryanstone, Dorset; Sir Henry Peyton, General Francis Cosbie)

- Lady Elizabeth Seymour (1552 – 3 June 1602), married Sir Richard Knightley, of Northamptonshire

Queen Jane stood godmother to Anne's first child. The ceremony was held at Chester Place; besides the queen, Thomas Cromwell and Mary Tudor also acted as godparents.[8]

Life in the royal court

Anne Seymour was present at the wedding ceremony of Henry VIII and Catherine Parr on 12 July 1543.[9] After Henry VIII's death, her husband acted as king in all but name. With this power, the Duchess of Somerset considered herself the first lady of the realm, claiming precedence over Henry VIII's widow, following the latter's marriage to the Duke of Somerset's brother, Thomas Seymour.

The Duchess considered that Catherine Parr forfeited her rights of precedence when she married the younger brother of the Duchess's husband.[10] She refused to bear Catherine's train, and allegedly physically tried to push her out of her place at the head of their entrances and exits at court.[11] The Duchess was quoted as having said of Catherine, "If master admiral (Thomas Seymour) teach his wife no better manners, I am she that will".[12] Catherine, in her turn, privately referred to her sister-in-law as "that Hell".[13] Catherine Parr won the battle by invoking the Third Succession Act which clearly stated that she had precedence over all ladies in the realm; in point of fact, as regards precedence, the Duchess of Somerset came after Catherine; Henry's daughters, Mary and Elizabeth; and Henry's former wife, Anne of Cleves. The Duchess, who was described as a "violent woman", wielded considerable power for a short time, which later would reflect negatively on her husband's reputation.

As lord protector, Edward Seymour wielded almost royal authority. However, he lost his position of power following a show-down between the Privy Council and himself in October 1549. He and his wife were imprisoned in the Tower of London.[14] The Duchess was released after a short time,[15] Somerset himself in January 1550.[16] According to the Imperial ambassador Jean Scheyfve, Anne Seymour had made daily visits to the house of the de facto new ruler, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, who soon allowed Somerset to rejoin the Privy Council. The Duchess of Somerset and the Countess of Warwick then arranged a marriage between their respective eldest daughter and son, Anne Seymour and John Dudley.[17]

Somerset fell again into disgrace in October 1551, when he was arrested on charges of conspiring against Warwick, who had recently been created Duke of Northumberland. They were taken again to Tower, and made lists of clothes they hoped to be sent to them. Anne Seymour asked for knitted hose and sleeves kept by her servant Mistress Susan, newly-made smocks and high-collared partlets and ruffs, laces kept by Mistress Purseby, a black gown, a plain black velvet kirtle, a farthingale, a stomacher of scarlet cloth, black and white embroidery thread, £20 to pay for washing, and utensils for dining.[18] Somerset was convicted of felony on 1 December 1551 and beheaded on 22 January 1552 on Tower Hill. The Duchess of Somerset had been arrested with her husband and continued in the Tower until 30 May 1553.[19] After Mary I's accession in July and the attainder of the Duke of Northumberland she was allowed to choose from the Dudley family's confiscated household stuffs.[20]

Second marriage

Anne Seymour married secondly Francis Newdigate (d. 26 January 1582) of Hanworth, Middlesex, who had been steward to her late husband. Newdigate was a younger son of John Newdigate, of Harefield, Middlesex.[21] Little is known of their life together.

Death

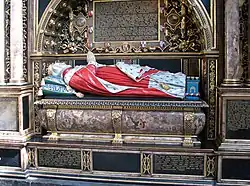

Anne Seymour died at Hanworth Palace,[22] Middlesex, on 16 April 1587, and was buried in Westminster Abbey,[23] where her tomb with its painted effigy can be viewed.

Jewels

In her will, Anne Seymour bequeathed to her "daughter of Hertford" (her daughter-in-law), Lady Katherine Grey, a fair tablet or locket "to wear with antique work on one side, and a rose of diamonds on the other". Antique work was renaissance-style ornament.[24]

Queen Elizabeth ordered an inventory of her jewels and money to be made by John Wolley and John Fortescue, master of her wardrobe. Her collection included a chain of gold pomander beads with "true-loves" or love knots of pearl and a red taffeta purse containing two pieces of unicorn horn.[25]

In 1551, some of her jewels were in the keeping of William Sharington of Lacock. These included brooches, tablets or lockets, one depicting Jacob's Ladder, another the story of the Samaritan woman, with a number of jewelled gold "billaments" for wearing on a French hood.[26]

In fiction

She was played by Kathleen Byron in the 1953 film Young Bess. She was played by Emma Hamilton in the historical fiction series The Tudors, in which her character is based partly on Edward Seymour's first wife, Catherine Fillol, who was rumoured to have had an affair with her father-in-law, and partly on the actual Anne Stanhope. In the series Anne is depicted as a woman who sleeps with many men and is known in France as a "woman of many talents" according to the Earl of Surrey. Her lovers on the show include Sir Francis Bryan and Sir Thomas Seymour (her brother-in-law). In the show, as a result of her affair with Sir Thomas, she has an illegitimate child with him, who is also named Thomas.

She was referenced in the show Becoming Elizabeth when Jane Grey attempted to console Catherine Parr, who had just learned that she was pregnant, that the Lord Protector's wife had survived 10 pregnancies. However, Parr retorted that she believed that nothing could kill the Lord Protector's wife.

References

- Marshall 1871, p. 7; Warnicke 2004

- Marshall 1871, p. 7.

- Marshall 1871, p. 7; Warnicke 2004; Davies 2004.

- Marshall 1871, p. 6.

- Anthony Martienssen, Queen Katherine Parr, p.125

- Martienssen, p.125

- Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII, p. 235

- Fraser. p. 275

- Martienssen, pp.153–54

- Martienssen, p. 231

- Martienssen, p.231

- Fraser, p.402

- Fraser, p. 403

- Loades p. 150

- Loades p. 150

- Beer, p. 95

- Beer, pp. 95–96

- Henry Ellis, Original Letters, 2nd series, vol. 2 (London, 1827), p. 215.

- Loades, pp. 188–190

- Beer, p. 196

- Cokayne 1953, p. 64.

- Warnicke 2004.

- Cokayne 1953, p. 64.

- Elizabeth Goldring, Faith Eales, Elizabeth Clarke, Jayne Elisabeth Archer, John Nichols's Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth: 1579-1595, vol. 3 (Oxford, 2014), pp. 386-390.

- John Strype, Annals of the Reformation, 3:2 (Oxford, 1824), pp. 447-9

- W. Gilchrist Clark, 'Unpublished Documents relating to the Arrest of William Sharington', Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, 27 (1894), pp. 165–170

Sources

- Cokayne, George Edward (1953). The Complete Peerage, edited by Geoffrey H. White. Vol. XII, Part I. London: St Catherine Press. pp. 59–65.

- Davies, Catharine (2004). "Page, Sir Richard (d. 1548)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/70795. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Marshall, George William, ed. (1871). The Visitations of the County of Nottingham in the Years 1569 and 1614. London: Harleian Society. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. p. 282. ISBN 978-1449966379.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stanhope, Philip Henry (1855). Notices of the Stanhopes as Esquires and Knights. London: A. and G.A. Spottiswoode. p. 9. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- Warnicke, Retha M. (2004). "Seymour, Anne, duchess of Somerset (c.1510–1587)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68053. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Barrett L. Beer, Northumberland: The Political Career of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick and Duke of Northumberland, 1973, The Kent State University Press; ISBN 0-87338-140-8

- David Loades: John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland 1504–1553, 1996, Clarendon Press; ISBN 0-19-820193-1

- Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1992; ISBN 0-394-58538-0

- Anthony Martienssen, Queen Katherine Parr, McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, St. Louis, San Francisco, Düsseldorf, Mexico, 1973; ISBN 0-07-040610-3