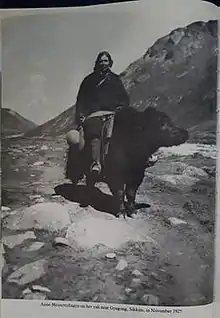

Annie Meinertzhagen

Annie Meinertzhagen (2 June 1889 – 6 July 1928)[1] was a Scottish ornithologist who contributed to studies on bird migration and was a specialist regarding waders and ducks, especially their moulting patterns.[2] She married fellow ornithologist Richard Meinertzhagen in 1921 and died from a gunshot fired under suspicious circumstances.

Annie Constance Jackson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 2 June 1889 Swordale, Ross-shire, Scotland |

| Died | 6 July 1928 (aged 39) Swordale, Ross-shire, Scotland |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Education | Imperial College London |

| Spouse | Richard Meinertzhagen |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | Honorary Member of the British Ornithological Union (1915) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | ornithology |

| Academic advisors | Ernest MacBride |

Early years

Born Anne Constance Jackson, her parents were Major Randle Jackson and Emily V. Baxter of Swordale, a village in eastern Ross-shire in the Scottish Highlands. Mrs Jackson was the daughter of Edward Baxter of Kincaldrum, Angus.[3]

Anne developed an early interest in natural history, especially in birds. With her younger sister Dorothy, who was to become an entomologist, she studied zoology for three years at the Imperial College of Science in London under Ernest MacBride.[1]

In 1915, she published a paper with MacBride in the Proceedings of the Royal Society on the inheritance of colour in the stick insect Carausius morosus.[4]

Much of her early ornithological work occurred while she was based in Swordale, in Ross and Cromarty, and along the firths of Cromarty and Dornoch she began publishing papers on the local birdlife in 1909.[1] She took an interest in bird migration and corresponded with lighthouse keepers who sent her specimens of rarities. She collected the first Scottish autumn specimens of the yellow-browed warbler and was the first ornithologist to demonstrate that the Icelandic race of the common redshank (Tringa totanus robusta) visits Britain.[5]

She often accompanied her cousin, Evelyn V. Baxter, during ornithological research.[6]

Marriage

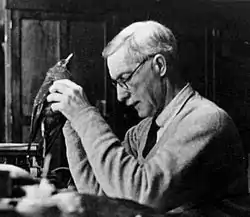

In March 1921, she married British soldier, intelligence officer and ornithologist Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen. She spent part of her honeymoon in research at Walter Rothschild's ornithological museum at Tring.[1]

In the further course of her ornithological studies she travelled to Copenhagen in 1921, to Egypt and Palestine in 1923, to Madeira in 1925, and to India in the winter of 1925–26, when she joined her husband in an expedition to Sikkim and southern Tibet hunting birds and mammals in the Himalayas.[1][5] She also gave birth to three children, Anne (born 1921), Daniel (born 1925) and Randle (born 1928).[7]

Annie Constance Meinertzhagen left £113,466 (net personalty £18,733) in her will to her husband if he should remain her widower and if he re-married he was to get an annuity of £1,200 and interest in their London home for life.[8]

Death

Annie Meinertzhagen died at her estate at Swordale on 6 July 1928, just over three months after the birth of her third child,[3] in an apparent shooting accident in the presence of her husband. The circumstances of her death were controversial, though no inquest or enquiry took place.[7] Richard Meinertzhagen's diary entry for 1 August 1928 reads:

”I have not written up my story for some weeks not because I have had nothing to say but because my heart has been too full of sorrow my soul too overwhelmed with unhappiness. My darling Annie died on July 6th as a result of a terrible accident at Swordale. We had been practising with my revolver and had just finished when I went to bring back the target. I heard a shot behind me and saw my darling fall with a bullet through her head.”[5]

Brian Garfield comments, in his exposé of Richard Meinertzhagen's life and character:[7]

”To those who believe that Annie’s death was no accident, the circumstantial evidence seems persuasive. The path of the bullet would seem to create doubt as to whether she could have inflicted the wound on herself. RM was at least a foot taller than his wife, so a downward shot through her head and spine – especially if she were leaning forward a bit – could have been fired much more readily by him than by her.

”It is argued that Annie would not likely have shot herself by accident. She was an expert with firearms, having grown up with them in the landed hunting set and having spent years hunting birds all over the world and providing specimens to the leading museums".

”Those who believe she was murdered point out that if ever in RM’s long and bloody career there was a smoking gun, this was that case – literally, with its bullet driven through Annie’s head and spine at point-blank range. They cite the standard homicide trinity; method, opportunity, and motive. Annie was shot to death at close range; her husband was the only witness; she died under suspicious circumstances at a time when her death was very much to his benefit because, they point out, it kept her from exposing his bird thefts, it freed him to carry on with his pubescent cousins, and it left him with a large income for life".

Publications

Annie Meinertzhagen's ornithological research was mainly concerned with waders and ducks. Under her maiden name she authored a series of articles on the moults of British ducks[9] and waders which formed the basis of her contributions on their plumages to Witherby's Practical Handbook of British Birds (1919–1924). Under her married name she made several important contributions to the Ibis, including review papers on the genus Burhinus in 1924, the subfamily Scolopacinae in 1926, and the family Cursoridae in 1927.[1][10]

Recognition

- 1915 – Honorary Lady Member of the British Ornithologists' Union

- 1919 – Corresponding Member of the American Ornithologists' Union

She is honoured in the subspecific name of the Antipodes snipe (Coenocorypha aucklandica meinertzhagenae), described by Walter Rothschild in 1927.[11] The subspecies Anthus cinnamomenus annae and Ammomanes deserti annae are also named in her honour.[12]

References

- T.S.P. (1928). "Obituary" (PDF). The Auk. 45: 539.

- Witherby, H.F. (1928). "Obituary. Annie Constance Meinertzhagen (nee Jackson)" (PDF). British Birds. 22 (3): 58–60.

- "Highland lady shot dead". Dundee Courier. 7 July 1928. p. 5 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- MacBride, E.W.; Jackson, A. (1915). "The Inheritance of Colour in the Stick-Insect, Carausius Morosus". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. 89 (611): 109–118. Bibcode:1915RSPSB..89..109M. doi:10.1098/rspb.1915.0034. JSTOR 80684.

- Mearns, Barbara; Mearns, Richard (1998). The Bird Collectors. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 357–359. ISBN 978-0-12-487440-4.

- Baxter, Evelyn (1908). "Bird notes from the Isle of May for the Year 1908". Annals of Scottish Natural History. 18: 5.

- Garfield, Brian (2007). The Meinertzhagen Mystery. The life and legend of a colossal fraud. Washington D.C.: Potomac Books. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-1-59797-041-9.

- "Rich lady's bequest to husband". Western Daily Press. 25 October 1928. p. 12 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Jackson, Annie C. (1915). "Notes on the moults and sequences of plumages in some British Ducks" (PDF). British Birds. 9 (2): 34–42.

- Jackson, Annie C. (1919). "The moults and sequences of plumages of the British Waders. Part 8" (PDF). British Birds. 12 (5): 104–113.

- Hartert, Ernst (1927). "Types of birds in the Tring Museum". Novitates Zoologicae. 34: 1–38.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (1 October 2014). The Eponym Dictionary of Birds. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472905741.