Anne Hathaway (wife of Shakespeare)

Anne Hathaway (1556 – 6 August 1623) was the wife of William Shakespeare, an English poet, playwright and actor. They were married in 1582, when Hathaway was 26 years old and Shakespeare was 18. She outlived her husband by seven years. Very little is known about her life beyond a few references in legal documents. Her personality and relationship to Shakespeare have been the subject of much speculation by many historians and writers.

Anne Hathaway | |

|---|---|

This drawing by Nathaniel Curzon, dated 1708, purportedly depicts Anne Hathaway. Samuel Schoenbaum writes that it is probably a tracing of a lost Elizabethan portrait, but there is no existing evidence that the portrait actually depicted Hathaway.[1] | |

| Born | 1556 Shottery, England |

| Died | 6 August 1623 (aged 66–67) Stratford-upon-Avon, England |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

Life

Anne Hathaway is believed to have grown up in Shottery, a village just to the west of Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. She is assumed to have grown up in the farmhouse that was the Hathaway family home, which is located at Shottery and is now a major tourist attraction for the village. Her father, Richard Hathaway, was a yeoman farmer. He died in September 1581 and left his daughter the sum of ten marks or £6 13s 4d (six pounds, thirteen shillings and fourpence) to be paid "at the day of her marriage".[2] In her father's will, her name is listed as "Agnes", leading to some scholars believing that she should be referred to as "Agnes Hathaway".[3]

Marriage

Hathaway married Shakespeare in November 1582, likely November 28, while already pregnant with the couple's first child, to whom she gave birth six months later. The age difference, added to Hathaway's antenuptial pregnancy, has been employed by some historians as evidence that it was a "shotgun wedding", forced on a somewhat reluctant Shakespeare by the Hathaway family. There is, however, no other evidence for this inference.

For a time it was believed that this view was supported by documents from the Episcopal Register at Worcester, which records in Latin the issuing of a wedding licence to "William Shakespeare" and one "Anne Whateley" of Temple Grafton. The following day, Fulk Sandells and John Richardson, friends of the Hathaway family from Stratford, signed a surety of £40 as a financial guarantee for the wedding of "William Shagspere and Anne Hathwey".[4] Frank Harris, in The Man Shakespeare (1909), argued that these documents are evidence that Shakespeare was involved with two women. He had chosen to marry one, Anne Whateley, but when this became known he was immediately forced by Hathaway's family to marry their pregnant relative. Harris believed that "Shakespeare's loathing for his wife was measureless" because of his entrapment by her and that this was the spur to his decision to leave Stratford and pursue a career in the theatre.[5]

However, according to Stanley Wells, writing in the Oxford Companion to Shakespeare, most modern scholars take the view that the name Whateley was "almost certainly the result of clerical error".[6]

Germaine Greer, in Shakespeare's Wife, argues that the age difference between Shakespeare and Hathaway is not evidence that he was forced to marry her, but that he was the one who pursued her. Women such as the orphaned Hathaway often stayed at home to care for younger siblings and married in their late twenties. As a husband Shakespeare offered few prospects; his family had fallen into financial ruin, while Hathaway, from a family in good standing both socially and financially, would have been considered a catch. Furthermore, a "handfast" and pregnancy were frequent precursors to legal marriage at the time. Examining the surviving records of Stratford-upon-Avon and nearby villages in the 1580s, Greer argues that two facts stand out quite prominently: first, that a large number of brides went to the altar already pregnant; and second, that autumn, not spring, was the most common time to get married. Shakespeare was bound to marry Hathaway, who had become pregnant by him, but there is no reason to assume that this had not always been his intention. It is nearly certain that the respective families of the bride and groom had known one another.[7]

Three children were born to Hathaway and her husband: Susanna in 1583 and the twins Hamnet and Judith in 1585. Hamnet died at 11 years old during one of the frequent outbreaks of the bubonic plague and was buried in Stratford-upon-Avon on 11 August 1596.

Apart from documents related to her marriage and the birth of her children, the only recorded reference to Hathaway in her lifetime is a curious bequest in the will of her father's shepherd, Thomas Whittington, who died in 1601. Whittington left 40 shillings to "the poor of Stratford", adding that the money was "in the hand of Anne Shakespeare wife unto Master William Shakespeare, and is due debt unto me, being paid to mine executor by the said William Shakespeare or his assigns according to the true meaning of this my will." This passage has been interpreted in several different ways. One view is that Whittington may have lent Anne the money, presumably because she was short of cash while her husband was away. More likely, however, it may have been "uncollected wages, or savings held in safekeeping", since the will also lists debts owed to him from her brothers in the same amount.[1]

In 1607, Hathaway's daughter Susanna married the local doctor, John Hall, giving birth to Hathaway's and Shakespeare's granddaughter, Elizabeth, the following year. Judith married Thomas Quiney, who was a vintner and tavern owner from a good family, in February 1616 when she was 31 and he was 27. Shakespeare may later have disapproved of this choice when it was discovered that Quiney had got another girl pregnant; also, Quiney had failed to obtain a special wedding licence needed during Lent, leading to Judith and Thomas being excommunicated on 12 March. Soon afterwards, on 25 March 1616, Shakespeare modified his will for Judith to inherit £300 in her own name, leaving Quiney out of the will and giving most of his property to Susanna and her husband.[8]

It has sometimes been inferred that Shakespeare came to dislike his wife, but there is no existing documentation or correspondence to support this supposition. For most of their married life, he lived in London, writing and performing his plays, while she remained in Stratford. However, according to John Aubrey, he returned to Stratford for a period every year.[9] When he retired from the theatre in 1613, he chose to live in Stratford with his wife, rather than in London.

Shakespeare's will

In his will Shakespeare famously made only one bequest to his wife, his "second-best bed with the furniture". There is no reference to the "best" bed, which would have been included in the main bequest to Susanna. This bequest to Anne has often been interpreted as a slight, implying that Anne was in some sense only the "second best" person in his intimate life.[10] A few explanations have been offered: first, it has been claimed that, according to law, Hathaway was entitled to receive one third of her husband's estate, regardless of his will,[11] though this has been disputed.[7] It has been speculated that Hathaway was to be supported by her children. Germaine Greer suggests that the bequests were the result of agreements made at the time of Susanna's marriage to Dr Hall: that she (and thus her husband) inherited the bulk of Shakespeare's estate. Shakespeare had business ventures with Dr Hall, and consequently appointed John and Susanna as executors of his will. Dr Hall and Susanna inherited and moved into New Place after Shakespeare's death.[8] This would also explain other examples of Shakespeare's will being apparently ungenerous, as in its treatment of his younger daughter Judith.

There is indication that Hathaway may have been financially secure in her own right.[7] The National Archives states that "beds and other pieces of household furniture were often the sole bequest to a wife" and that, customarily, the children would receive the best items and the widow the second-best.[12] In Shakespeare's time, the beds of prosperous citizens were expensive affairs, sometimes equivalent in value to a small house. The bequest was thus not as minor as it might seem in modern times.[7] In Elizabethan custom, the best bed in the house was reserved for guests. If so, then the bed that Shakespeare bequeathed to Anne could have been their marital bed, and thus not intended to insult her.

However, the will as initially drafted did not mention Anne at all. It was only through a series of additions, made on 25 March 1616, slightly less than a month before Shakespeare died, that the bequest to his wife of his "second best bed with the furniture" was made. Author Stephen Greenblatt in Will in the World, suggests that as Shakespeare lay dying, "he tried to forget his wife and then remembered her with the second-best bed. And when he thought of the afterlife, the last thing he wanted was to be mingled with the woman he married. There are four lines carved in [Shakespeare's] gravestone in the chancel of Stratford Church: Good friend for Jesus sake forbeare, To digg the dust encloased heare: Bleste be ye man y't spares thes stones, And curst be he y't moves my bones. [Shakespeare may have] feared that his bones would be dug up and thrown in the nearby charnel house ... but he may have feared still more that one day his grave would be opened to let in the body of Anne Shakespeare."[13]

Burial

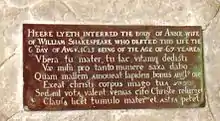

A tradition recorded in 1693 is that Hathaway "greatly desired" to be buried with her husband.[10] In fact she was interred in a separate grave next to him in the Church of the Holy Trinity, Stratford-upon-Avon. The inscription states, "Here lyeth the body of Anne wife of William Shakespeare who departed this life the 6th day of August 1623 being of the age of 67 years." A Latin inscription followed which translates as "Breasts, O mother, milk and life thou didst give. Woe is me—for how great a boon shall I give stones? How much rather would I pray that the good angel should move the stone so that, like Christ's body, thine image might come forth! But my prayers are unavailing. Come quickly, Christ, that my mother, though shut within this tomb may rise again and reach the stars."[14] The inscription is believed to have been written by John Hall on behalf of his wife, Anne's daughter, Susanna.[4]

In literature

Shakespeare's sonnets

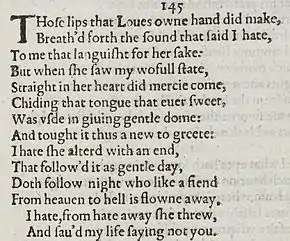

One of Shakespeare's sonnets, number 145, has been claimed to make reference to Anne Hathaway: the words 'hate away' may be a pun (in Elizabethan pronunciation) on 'Hathaway'. It has also been suggested that the next words, "And saved my life", would have been indistinguishable in pronunciation from "Anne saved my life".[15] The sonnet differs from all the others in the length of the lines. Its fairly simple language and syntax have led to suggestions that it was written much earlier than the other, more mature, sonnets.

Those lips that Love's own hand did make

Breathed forth the sound that said 'I hate'

To me that languish'd for her sake;

But when she saw my woeful state

Straight in her heart did mercy come,

Chiding that tongue that ever sweet

Was used in giving gentle doom,

And taught it thus anew to greet:

'I hate' she alter'd with an end,

That follow'd it as gentle day

Doth follow night, who like a fiend

From heaven to hell is flown away;

'I hate' from hate away she threw,

And saved my life, saying 'not you.'

Other literature

The following poem about Anne has also been ascribed to Shakespeare, but its language and style are not typical of his verse. It is widely attributed to Charles Dibdin (1748–1814) and may have been written for the Stratford-upon-Avon Shakespeare Festival of 1769:[16]

But were it to my fancy given

To rate her charms, I'd call them heaven;

For though a mortal made of clay,

Angels must love Anne Hathaway;She hath a way so to control,

To rapture the imprisoned soul,

And sweetest heaven on earth display,

That to be heaven Anne hath a way;She hath a way,

Anne Hathaway,—

To be heaven's self Anne hath a way.

Fictional portrayals

Anne is depicted in fiction during the 19th century, when Shakespeare started to become a figure in wider national and popular culture. Emma Severn's novel Anne Hathaway, or, Shakespeare in Love (1845) portrays an idealised romance and happy marriage in an idyllic rural Stratford.[17] She also appears in William Black's 1884 novel Judith Shakespeare about her daughter, portrayed as a conventional dutiful wife and concerned parent with a wayward daughter.[18]

By the early 20th century a more negative image of Hathaway emerged, following the publication of Frank Harris's books on Shakespeare's love life, and after the discovery that Anne was already pregnant when the couple married. A trend in literature on Hathaway in this period was to imagine her as a sexually incontinent cradle-snatcher, or, alternatively, a calculating shrew. More recent literature has included more varied representations of her. Historian Katherine Scheil describes Hathaway as a "wife-shaped void" used by modern writers "as a canvas for expressing contemporary woman's struggles—over independence, single motherhood, sexual freedom, unfaithful husbands, woman's education and power-relations between husband and wife."[19]

An adulterous Anne is imagined by James Joyce's character Stephen Dedalus, who makes a number of references to Hathaway.[20] In Ulysses, he speculates that the gift of the infamous "second-best bed" was a punishment for her adultery,[21] and earlier in the same novel, Dedalus analyses Shakespeare's marriage with a pun: "He chose badly? He was chosen, it seems to me. If others have their will Ann hath a way."[22] Anne also appears in Hubert Osborne's The Shakespeare Play (c. 1911) and its sequel The Good Men Do (1917), which dramatises a meeting between the newly widowed Anne and her supposed old rival for William's love "Anne Whateley". Anne is depicted as shrewish in the first play, and as spiteful towards her former rival in the latter.[23] William Gibson's play A Cry of Players (1968) portrayed the young Shakespeare and Anne and was performed on Broadway (at Lincoln Center) with Frank Langella and Anne Bancroft as the couple. A frosty relationship is also portrayed in Edward Bond's play Bingo: Scenes of Money and Death (1973), about Shakespeare's last days, and in the 1978 TV series Will Shakespeare.

The World's Wife, a collection of poems by Carol Ann Duffy, features a sonnet entitled "Anne Hathaway", based on the passage from Shakespeare's will regarding his "second-best bed". Duffy chooses the view that this would be their marriage bed, and so a memento of their love, not a slight. Anne remembers their lovemaking as a form of "romance and drama", unlike the "prose" written on the best bed used by guests, "I hold him in the casket of my widow's head/ as he held me upon that next best bed". In Robert Nye's novel Mrs Shakespeare: the Complete Works, which purports to be Anne's autobiographical reminiscences, Shakespeare buys the best bed with money given to him by the Earl of Southampton. When Anne comes to London, the couple use the bed for wild sexual adventures, in which they engage in role-playing fantasies based on his plays. He refers to the bed he bequeaths her as "the second best" to remind her of the best bed of their memories. The novel was dramatised for BBC radio in 1998 with Maggie Steed playing Hathaway.

The Connie Willis short story "Winter's Tale," which combines factual information about Anne Hathaway with a fictitious Shakespeare identity theory, also characterises the nature of the relationship as loving and the bequeath of the second-best bed as romantically significant.

Anne Hathaway appears in Neil Gaiman's comic book section "The Tempest", part of The Sandman series. She and Shakespeare share a tumultuous, yet affectionate, relationship. Gaiman's interpretation suggests that Anne deliberately became pregnant to force her husband to marry her, but the context implies that neither of them ultimately regret their decision.

Through her long-running solo show Mrs Shakespeare, Will's first and last love (1989) American actress-writer Yvonne Hudson has had a long relationship with both the historical and dramatic Anne Hathaway. She depicts Anne and Will as maintaining a friendship despite the challenges inherent to their long separations and tragedies. Mining early and recent scholarship and the complete works, Hudson concurs that evidence of the couple's mutual respect is indeed evident in the plays and sonnets, along with support for the writer's infatuations and possibly adulterous relationships. Hudson also chooses the positive view of the bed bequest, sharing that "it may have been only here that I possessed William." Mrs Shakespeare explores the realities of keeping house without a husband while applying some dramatic licence. This allows Anne to have at least a country wife's understanding of her educated spouse's work as she quotes sonnets and soliloquies to convey her feelings. The 2005 play Shakespeare's Will by Canadian playwright Vern Thiessen is similar in form to Hudson's show. It is a one-woman piece that focuses on Anne Hathaway on the day of her husband's funeral. Avril Rowland's Mrs Shakespeare (2005) depicts Anne as a multi-tasking "superwoman" who runs the home efficiently while also writing her husband's plays in a businesslike partnership with him as her promoter/performer.[19]

The romantic comedy film Shakespeare in Love provides an example of the negative view, depicting the marriage as a cold and loveless bond that Shakespeare must escape to find love in London. The same situation occurs in Harry Turtledove's alternate-history novel Ruled Britannia (2002), in which Shakespeare seeks and actually wins a divorce from Hathaway to marry his new girlfriend. A similarly loveless relationship is depicted in the film A Waste of Shame (2005).

The Secret Confessions of Anne Shakespeare (2010), a novel by Arliss Ryan, also proposes Anne Hathaway as the true author of many of the Shakespeare plays (a claim originally made in 1938[24]). In the novel, Anne follows Will to London to support his acting career. As he finds his true calling in writing, Anne's own literary skills flower, leading to a secret collaboration that makes William Shakespeare the foremost playwright in Elizabethan England.

She is portrayed by Liza Tarbuck in the BBC Two comedy series Upstart Crow, which follows the writing and preparation to stage Romeo and Juliet after William has gained some early career notoriety for his poetry, Henry VI and Richard III.

Anne Hathaway is portrayed by Judi Dench in the 2018 historical film All Is True.

Anne is portrayed by actress Cassidy Janson in the musical & Juliet. The show opened in the West End on 20 November 2019. The show transferred to Broadway in 2022. It officially opened on 17 November 2022. In the Broadway production, Anne is portrayed by Betsy Wolfe.

Anne Hathaway is a main character in Maggie O'Farrell's 2020 novel Hamnet, a fictional account of Shakespeare's family centered on the death of their only son. It won the Women's Prize for Fiction in the same year.

Anne Hathaway's Cottage

Anne Hathaway's childhood was spent in a house near Stratford-upon-Avon in Warwickshire, England. Although it is often called a cottage, it is, in fact, a spacious twelve-roomed farmhouse, with several bedrooms, now set in extensive gardens. It was known as Hewlands Farm in Shakespeare's day and had more than 90 acres (36 hectares) of land attached to it. As in many houses of the period, it has multiple chimneys to spread the heat evenly throughout the house during winter. The largest chimney was used for cooking. It also has visible timber framing, a trademark of vernacular Tudor style architecture.

After the death of Anne's father, the cottage was owned by Anne's brother Bartholomew, and was passed down the Hathaway family until 1846, when financial problems forced them to sell it. It is now owned and managed by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, and is open to public visitors as a museum.[2]

See also

References

- Schoenbaum, Samuel (1987). William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life (Revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 92, 240. ISBN 0-19-505161-0.

- "Anne Hathaway's Cottage & Gardens – Shakespeare Birthplace Trust". shakespeare.org.uk. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008.

- Pogue, Kate (2008). Shakespeare's Family. Greenwood. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-275-99510-2.

- Stanley Wells, "Hathaway, Anne". Oxford Companion to Shakespeare, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 185. Sandells had overseen the drawing up of Richard Hathaway's will and Richardson had been a witness.

- Frank Harris, The Man Shakespeare, BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2007, (reprint) p. 362.

- Stanley Wells, "Whateley, Anne". Oxford Companion to Shakespeare, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 185, 518. See also Park Honan, Shakespeare: a life, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 84.

- Greer, Germaine (2008). Shakespeare's Wife. New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-153715-8.

- "The Children of William Shakespeare". literarygenius.info.

- Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor, John Jowett, William Montgomery, William Shakespeare, a textual companion, W. W. Norton & Company, 1997, p. 90

- Marjorie Garber, Profiling Shakespeare, Routledge, 2008, pp. 170–175.

- Best, Michael (2005) Anne's inheritance. Internet Shakespeare Editions, University of Victoria, Canada.

- "Shakespeare's will". The National Archives (UK government).

- Stephen Greenblatt, Will in the World, How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 2004.

- Vbera, tu mater, tu lac, vitamque dedisti. / Vae mihi: pro tanto munere saxa dabo / Quam mallem, amoueat lapidem, bonus angelus orem / Exeat Christi corpus, imago tua~~ / Sed nil vota valent. venias citò Christe; resurget / Clausa licet tumulo mater et astra petet.

- Shakespeare-ssonnets.com. Retrieved 19 April 2007

- Shakespeare and Precious Stones by George Frederick Kunz

- Watsaon, Nicola, "Shakespeare on the Turist Trail", Robert Shaughnessy (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Popular Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 211.

- Black, William, Judith Shakespeare, her Love Affairs and Other Adventures, New York, 1884.

- Katherine Scheil, "Filling the Wife-Shaped Void: The Contemporary Afterlife of Anne Hathaway", Peter Holland (ed), Shakespeare Survey: Volume 63, Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 225ff.

- Robotwisdom.com Archived 13 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 19 April 2007

- Robotwisdom.com Archived 1 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 19 April 2007

- Robotwisdom.com Archived 1 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 19 April 2007

- "The Good Men Do" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- R. C. Churchill, Shakespeare and His Betters: A History and a Criticism of the Attempts Which Have Been Made to Prove That Shakespeare's Works Were Written by Others, Max Reinhardt, London, 1958, p. 54. Churchill refers to an article entitled "The Plays of Mrs. Shakespeare" by J. P. de Fonseka in G.K's Weekly, 3 March 1938.

.png.webp)