Anne Locke

Anne Locke (Lock, Lok) (c.1533 – after 1590) was an English poet, translator and Calvinist religious figure. She has been called the first English author to publish a sonnet sequence, A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner (1560), although authorship of that work has been attributed on strong grounds to Thomas Norton.[1][2]

Life

Anne was a daughter of Stephen Vaughan, a merchant, royal envoy, and prominent early supporter of the Protestant Reformation. Her mother was Margaret (or Margery) Gwynnethe (or Guinet), sister of John Gwynneth, rector of Luton (1537-1558) and of St Peter, Westcheap in the City of London (1543-1556). Stephen and Margaret's marriage followed the death of her first husband, Edward Awparte, citizen and Girdler, in 1532, by whom she had five children.[3] Anne was the eldest surviving child of her second marriage, and had two siblings, Jane and Stephen (b. 4 October 1537). Vaughan obtained a position for his wife as silkwoman to both Anne Boleyn and Catherine Parr.[4] Following her death in 1544,[5] Anne's father took great efforts to find a tutor for the children, selecting a Mr. Cob, who was proficient in Latin, Greek, and French, as well as a dedicated Protestant. Stephen Vaughan remarried in April 1546, to Margery Brinklow, the widow of Henry Brinklow, mercer and polemicist, a long-time acquaintance of the Vaughan family.[6] Vaughan died on 25 December 1549, leaving most of his property to his widow and son, with the rents of one house in Cheapside going to his daughters. John Gwynneth was his executor.[7]

In c.1549 Anne married Henry Locke (Lok), a younger son of the mercer Sir William Lok.[8] In 1550, Sir William died, leaving a substantial inheritance to Henry, which included several houses, shops, a farm, and freehold lands. In 1553 the notable Scottish reformer and preacher John Knox lived for a period in the Lok household during which time he and Locke seem to have developed a strong relationship, attested to by their correspondence over the following years. Following the ascension of Mary Tudor, and the accompanying pressure on English nonconformists which saw Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley executed in 1555, Knox encouraged Lock to leave London and join the exiled Protestant community in Geneva. Knox seems to have been worried both for her physical safety and her spiritual health if she remained in London. Henry Lok seems to have been resistant to the idea of entering into exile, as Knox argues that Anne should "call first for grace by Jesus to follow that whilk is acceptabill in his sight, and thairefter communicat" with her husband.[4]

In 1557, Anne managed to leave London. She is recorded to have arrived in Geneva on 8 May 1557, accompanied by her daughter, son, and maid Katherine. Within four days of their arrival, her infant daughter had died.[4] There is no contemporary record of this period, however it is believed that Locke spent her 18 months exile translating John Calvin's sermons on Hezekiah from French into English. Henry Locke remained in London whilst Anne was in Geneva.

In 1559, after the accession of Elizabeth I, Anne and her surviving son, the young Henry Locke, who would become known as a poet, returned to England and to her husband. The following year, Locke's first work was published. This consisted of a dedicatory epistle to Katherine Willoughby Brandon Bertie (the dowager Duchess of Suffolk), a translation of John Calvin's sermons on Isaiah 38, and a twenty-one sonnet paraphrase on Psalm 51, prefaced by five introductory sonnets. The volume was printed by John Day, and entered into the Stationers' Register on 15 January 1560. The volume seems to have been popular as it was reprinted in 1569 and 1574 by John Day, although no copies remain of these two editions.

Knox and Anne continued to correspond. On 7 February 1559 Lock wrote to Knox asking for his advice on the sacraments administered by the second Book of Common Prayer, and the seemliness of attending baptisms. He strongly encouraged her to avoid services where ceremonies might outweigh worship, but recognised her personal spiritual wisdom, saying 'God grant yow his Holie Spirit rightlie to judge'.[4] Knox sent Anne reports from Scotland of his reforming endeavours, and asked her repeatedly to help him find support among London merchants. During this period, Anne gave birth to at least two children, Anne (baptised 23 October 1561)and Michael (baptised 11 October 1562). Henry Locke died in 1571, leaving all his worldly goods to his wife. In 1572 Anne married the young preacher and gifted Greek scholar, Edward Dering, who died in 1576. Her third husband was Richard Prowse of Exeter. In 1590 she published a translation of a work of Jean Taffin.[9][10][11][12]

Works

Scholars disagree whether or not Anne Locke wrote the first sonnet sequence in English, A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner; it comprises 26 sonnets based on Psalm 51. Locke's other works include a short, four-line Latin poem that appears in a 1572 manuscript of Doctor Bartholo Sylva's Giardino cosmographico coltivato alongside many other dedicatory poems. The manuscript was compiled for presentation to Robert Dudley by Locke, her second husband Edward Dering, and the five Cooke sisters, all staunch supporters of the Protestant cause.[13] Locke’s piece puns on Sylva’s name to testify to his prose, the experience of which is as delightful as a walk through a forest.[14]

The last known work by Locke is a 1590 translation of Of the Markes of the Children of God, a treatise written by the Belgian minister Jean Taffin about the history of Protestantism in Belgium and the other Low Countries. Like her 1560 translation of John Calvin's sermons, this volume ends with an original poem, though only a single short one titled The necessitie and benfite of affliction. It also contains a dedicatory epistle to the Duchess of Warwick, who shared Locke's reformist religious sensibilities.[15]

Two printed contemporary references to Locke's poetry and translations evince diverse reactions to religious material produced by a woman. In 1583, John Field printed an edition of Locke's manuscript of a sermon by John Knox, entitled A Notable and Comfortable Exposition upon the Fourth of Matthew. Field's dedication to the volume praises Locke for her willingness to endure exile for religious reform, as well as for her access to the works, in manuscript, of prominent preachers like Knox. The printer urges her to grant him access to more such manuscripts. In contrast, Richard Carew, in the 1602 Survey of Cornwall, specifically praises Locke's intellectual prowess in tandem with her modesty, asserting that her virtuous behaviour evinced her religious learning, in addition to her writing.[16]

A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner

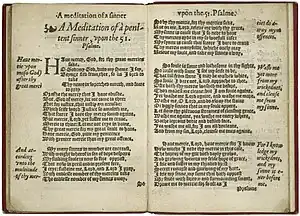

This sonnet sequence was published in 1560 alongside Locke's translations of four of John Calvin's sermons on Isaiah 38, in a volume titled Sermons of John Calvin upon the Songe that Ezechias made after he had bene sicke...Translated out of Frenche into Englishe.[17] Locke probably had access to Calvin's manuscripts, which enabled her to make a close translation of the sermons.[18] In the 1560 edition, the translations and sonnets were prefaced by a letter of dedication to Catherine Brandon, duchess of Suffolk.[19] The duchess, a longtime patron of Protestant writers, also lived in exile during the reign of Mary I; Locke may have known her through their sons, who were both educated at the home of William Cecil.[20] The volume was entered into the Stationers' Register on 15 January 1560 by John Day, a printer known for his publication of Protestant and reformist texts.

The sequence begins with five prefatory sonnets, printed under the heading "The preface, expressing the passioned mind of the penitent sinner." Another heading, "A Meditation of a penitent sinner, upon the 51. Psalme," introduces the remaining twenty-one poems in the sequence. The "Meditation" poems gloss the nineteen-line psalm line by line, with a few expansions: the author gives two sonnets each to the first and fourth lines of the psalm; these comprise the first, second, fifth, and sixth poems in the sequence. In the 1560 edition, each line of the psalm appears beside its corresponding poem. This version of the psalm may have been translated by Locke.[19][21]

Poetics

A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner is one work in a long tradition of poetic meditation on the Psalms. The sequence develops the penitential poetic mode that was also used by late medieval poets.[22] While both Catholics and Protestants composed poetry in the penitential tradition, Protestant reformers were particularly drawn to Psalm 51 because its emphasis on faith over works favoured their reformist theology.[23][24]

The author of the sequence was probably influenced by Sir Thomas Wyatt's translations of the penitential psalms, published in 1549 and accessible to Locke before her Genevan exile. Wyatt's influence is evident in the pattern of psalm lines glossed. Both the author of the sequence and Wyatt composed one sonnet per line of the psalm, except for verses 1 and 4, which are each glossed with two poems. The author's enjambment is also similar to Wyatt's.[25]

Though the sonnet was not an established form of English poetry while the author composed the sequence, the author both uses and disregards features of the sonnet circulating the island during the sixteenth century. It is likely that, in addition to Wyatt's work, the author also had access to the sonnets of the Earl of Surrey, as the author uses Surrey's rhyme scheme, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, now best known as the Shakespearean rhyme scheme. Wyatt's Psalm translations may also have introduced the author to Surrey's work, as his volume contains a prefatory sonnet by Surrey. The author seems to have drawn upon the arrangement of this particular poem, which does not contain the Petrarchan break between octave and sestet. In using this form consistently, the author sets him/herself apart from other early English sonnet writers, who generally ascribed to the traditional Petrarchan octave/sestet pair.[26]

Authorship

Authorship of the sonnet sequence and the translations of Calvin's sermons was first ascribed to Locke by critic Thomas Roche in 1989, in Petrarch and the English Sonnet Sequences. Roche is thus also the first scholar to name her as the author of the first sonnet sequence in English.[27] Recent work by Stephen W. May, an authority on Tudor manuscripts, attributes the sequence to Locke's close contemporary, neighbor, and co-religionist Thomas Norton, however.[28]

Though the volume's dedication to the Duchess of Suffolk is only signed "A.L.", it is likely that Locke's identity remained identifiable to London's community of English Church reformers,[29] many of whom, like Locke, lived in exile in Geneva during the reign of Mary I.[30] The inclusion of her initials, rather than her full name, allowed her to avoid both perils that plagued female writers during the period – anonymity and full exposure – who were branded as unchaste if their material was accessible to the broader public.[31] The choice of psalm to translate and gloss arguably favours the case for her authorship of the sequence, and helps her negotiate sixteenth-century England's condemnation of a woman writer as unchaste. Psalm 51 specifies that the experience of God's forgiveness includes speaking God's praise, framing speech as a duty.[31][32]

Some of those who dispute Locke's authorship of the sequence ascribe its authorship to John Knox. When Knox communicated with Locke, however, he wrote in Scots English and would have composed poems in the same dialect; the Meditation sonnets show no grammatical or idiomatic sign of Scots English.[33] According to Stephen May, a much more likely candidate for authorship of the sequence is Thomas Norton.[34]

Editions

- Kel Morin-Parsons (editor) (1997), Anne Locke. A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner: Anne Locke's Sonnet Sequence with Locke's Epistle

- Susan Felch (editor) (1999), The Collected Works of Anne Vaughan Lock

Family connections

Anne's family background was a dense web of relationships involving the Mercers' Company, the court, Marian exiles and notable religious figures. Her father, Stephen Vaughan, was a merchant and diplomatic agent for Henry VIII. Her mother Margaret or Margery was firstly the wife of Edward Awpart, citizen and Girdler of London in the parish of St Mary le Bow, who originated from Penkridge in Staffordshire. The Awparts had five children, Elizabeth, Anne, Joan, Edward and Susan, who were all unmarried at the time of their father's death in 1532.[35] Through his connection to Thomas Cromwell, Stephen Vaughan found a position for Anne's mother as silkwoman to Anne Boleyn.[36] His second wife, Anne's stepmother Margery, was the widow of Henry Brinklow, mercer and polemicist,[6] and went on to make two further marriages.[37]

Henry Lok was a mercer and one of many children of the mercer William Lok, who married four times;[38] William Lok was also connected to Cromwell. Anne's sister-in-law, and one of Henry Lok's sisters, was Rose Lok (1526–1613), known as a Protestant autobiographical writer, married to Anthony Hickman.[39] Another of Henry Lok's sisters, Elizabeth Lok, married Richard Hill; both Rose and Elizabeth were Marian exiles. Elizabeth later married Bishop Nicholas Bullingham after his first wife died (1566).[40] Michael Lok was a backer of Martin Frobisher, and married Jane, daughter of Joan Wilkinson, an evangelical associate of Ann Boleyn and her chaplain William Latimer.[41][42]

References

- P. Collinson, 'Locke [née Vaughan; other married names Dering, Prowse], Anne (c. 1530–1590x1607)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004).

- Steven W. May, "Anne Lock and Thomas Norton's Meditation of a Penitent Sinner", Modern Philology 114.4 (2017), 793-819.

- Will of Edward Awparte, Girdler of London (P.C.C. 1532).

- Felch, ed. Susan M. (1999). The Collected Works of Anne Vaughan Lock. Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies in conjunction with Renaissance English Text Society. pp. xxv–xxvi. ISBN 0866982272.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - M.K. Dale, 'Vaughan, Stephen (by 1502-49), of St. Mary-le-Bow, London', in S.T. Bindoff (ed.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558 (from Boydell and Brewer, 1982), History of Parliament online.

- "Anne Vaughan Lock". Litencyc.com. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Fry, ed. George S. (1968) [1896–1908]. Abstracts of Inquisitiones Post Mortem Relating to the City of London, returned into the Court of Chancery, 3 vols (reprint ed.). Lichenstein: Nendeln. pp. 1:80–3.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - R. O'Day, 'Lock Anne, née Vaughan', The Routledge Companion to the Tudor Age, Routledge Companions to History (Routledge, London/New York 2010), p. 197 (Google).

- Diana Maury Robin, Anne R. Larsen, Carole Levin, Encyclopedia of Women in the Renaissance: Italy, France, and England (2007), p. 219.

- Patrick Collinson, Elizabethan Essays (1994), p. 123.

- Francis J. Bremer, Tom Webster, Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia (2006), p. 74 and p. 161.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 November 2009. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Susan M. Felch, "The Exemplary Anne Vaughan Lock," in Intellectual Culture of Puritan Women, 1558–1680, ed. Johanna Harris and Elizabeth Scott-Baumann (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 23.

- Susan M. Felch, introduction to The collected works of Anne Vaughan Locke, by Anne Vaughan Locke (Tempe: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1999), lvii–lix.

- Micheline White, "Women Writers and Literary-Religious Circles in the Elizabethan West Country: Anne Dowriche, Anne Lock Prowse, Anne Locke Moyle, Ursula Fulford, and Elizabeth Rous,” Modern Philology 103 (2005):198.

- White, "Women Writers," 201–202.

- Michael R. G. Spiller, "A Literary 'First': The Sonnet Sequence of Anne Locke (1560)," Renaissance Studies: Journal of the Society for Renaissance Studies 11 (1997):42.

- Teresa Lanpher Nugent, “Anne Locke’s Poetics of Spiritual Abjection,” English Literary Renaissance 39 (2009):3–5.

- Spiller, "A Literary 'First'," 41.

- Felch, introduction to '’The collected works of Anne Vaughan Locke'’, xxxvi.

- Nugent, “Anne Lock’s Poetics of Spiritual Abjection,” 10.

- Ruen-chuan Ma, “Counterpoints of Penitence: Reading Anne Locke’s “A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner” through a Late-Medieval Middle English Psalm Paraphrase,” ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews 24 (2011): 33–41.

- Nugent, “Anne Lock’s Poetics of Spiritual Abjection,” 7.

- Spiller, “A Literary ‘First’,” 46.

- Spiller, "A Literary 'First'," 46–48.

- Spiller, "A Literary 'First'," 49.

- Spiller, "A Literary 'First'," 42.

- May, "Anne Lock"

- Serjeantson,'Anne Lock's Anonymous Friend: A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner and the Problem of Ascription', in Enigma and Revelation in Renaissance Literature, ed. by Helen Cooney and Mark S. Sweetnam (Dublin, 2012), 51–68.

- Nugent, “Anne Locke’s Poetics of Spiritual Abjection,” 3–4.

- Nugent, “Anne Locke’s Poetics of Spiritual Abjection,” 8.

- Margaret P. Hannay, ""Wisdome the Wordes": Psalm Translation and Elizabethan Women’s Spirituality," Religion and Literature 23 (1991):65–66.

- Spiller, "A Literary 'First'," 51.

- May, "Anne Lock"

- Will of Edward Awpart, "Girdler" (mis-written "Gardener" in Discovery Catalogue of TNA (UK)) of London (P.C.C. 1532, Thower quire, m/film imgs 237-38): PROB 11/24/211 and PROB 11/24/220.

- Retha M. Warnicke, The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn: Family Politics at the Court of Henry VIII (Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 136 (Google).

- A.D.K. Hawkyard, 'Rolle, George (by 1486-1552), of Stevenstone, Devon and London', in S.T. Bindoff (ed.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558 (from Boydell and Brewer 1982), History of Parliament Online.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Cathy Hartley, Susan Leckey, A Historical Dictionary of British Women (2003), p. 217.

- Dictionary of National Biography, article on Bullingham.

- Mary Prior, Women in English Society, 1500–1800 (1985), p. 98.

- Maria Dowling, Humanism in the age of Henry VIII (1986), p. 241.