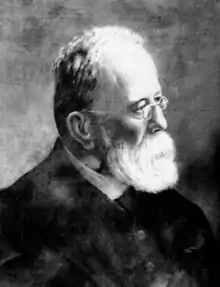

Anselmo Lorenzo

Anselmo Lorenzo Asperilla (21 April 1841, in Toledo, Spain – 30 November 1914) was a defining figure in the early Spanish Anarchist movement, earning the often quoted sobriquet "the grandfather of Spanish anarchism," in the words of Murray Bookchin: "his contribution to the spread of Anarchist ideas in Barcelona and Andalusia over the decades was enormous".[1]

Anselmo Lorenzo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 April 1841 Toledo, Spain |

| Died | 30 November 1914 |

| Resting place | Cemetery of Montjuïc |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Organization | International Workingmen's Association |

| Known for | "the grandfather of Spanish anarchism" |

His activity in the movement and adherence to Anarchist ideals can be rooted to his meeting and befriending of Giuseppe Fanelli in 1868, a disciple of Mikhail Bakunin recruiting for the International Workingmen's Association.[2] He would later become the subject of Lorenzo's works, along with Tomás González Morago, who an account considered the first Spanish Anarchist.[3]

Paul Lafargue recruited Lorenzo and other Madrilenian printers (such as Pablo Iglesias and Jose Mesa) for the Spanish Regional Federation of the IWA.[4] This association with Lafargue, a son-in-law of Karl Marx, led to the founding of the Madrid Internationalist paper called La Emancipacion, which promoted Marxist ideology.[4] Lorenzo was listed as one of the delegates representing the Spanish Marxists in the International Workingmen's Association (IWMA) London Congress in 1864.[5]

Lorenzo edited the anarchist syndicalist newspaper La Huelga General from 1901 to 1902 with Francisco Ferrer.[6] He died on 30 November 1914 and was laid to rest on the Cemetery of Montjuïc.

References

- Bookchin, Murray (1977). The Spanish Anarchists: The Heroic Years, 1868–1936. Free Life Editions. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-914156-14-7.

- Barsky, Robert F. (2007). The Chomsky Effect: A Radical Works Beyond the Ivory Tower. MIT Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-262-02624-6.

- Brenan, Gerald (2014). The Spanish Labyrinth: An Account of the Social and Political Background of the Spanish Civil War, Canto Classics Edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-107-43175-1.

- Esenwein, George Richard (1989). Anarchist Ideology and the Working-class Movement in Spain, 1868-1898. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-520-06398-8.

- Holmes, Rachel (2014). Eleanor Marx: A Life. London: A&C Black. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7475-8384-4.

- Steele, Tom (2007). Knowledge is Power!: The Rise and Fall of European Popular Educational Movements, 1848-1939. Peter Lang. p. 114. ISBN 978-3-03910-563-2.

Further reading

- Álvarez Junco, José (May 1975). "Anselmo Lorenzo y su tiempo". Tiempo de Historia. 1 (6): 45–55.

- Díaz Díaz, Gonzalo (1991). "Lorenzo Asperilla, Anselmo". Hombres y documentos de la filosofía española. Vol. 4. Madrid: CSIC. ISBN 978-84-00-07198-1.

- Lane, A. T. (1995). Biographical Dictionary of European Labor Leaders. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-26456-6.

- Montseny, Federica (1977). Vida y obra de Anselmo Lorenzo. Madrid: Libros Dogal. ISBN 978-84-7463-004-6. OCLC 4189619.

- Thomas, Paul (1985). Karl Marx and the Anarchists (Reprint ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7102-0685-5.

- Villena Espinosa, Rafael (2009). Anselmo Lorenzo (1841-1914): el proletario militante. Toledo: Almud. ISBN 978-84-935656-4-0. OCLC 733645568.