Antankarana

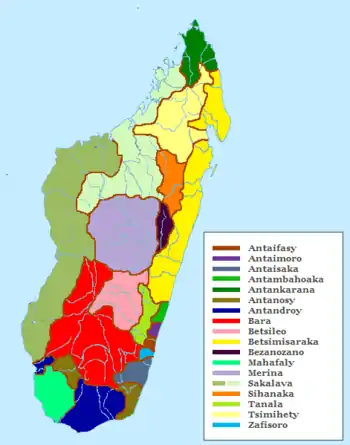

The Antankarana (or Antakarana) are an ethnic group of Madagascar inhabiting the northern tip of Madagascar, around Antsiranana. Their name means "the people of the tsingy," the limestone rock formations that distinguish their traditional territory. The tsingy of the Antankarana may be visited at the Ankarana Reserve. There are over 50,000 Antakarana in Madagascar as of 2013.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| over 50,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Madagascar | |

| Languages | |

| Malagasy | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (syncretic with traditional beliefs) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Malagasy groups, Austronesian peoples, Bantu peoples |

The Antankarana split off from the Sakalava in the early 17th century following a succession dispute. The group settled at the northern end of the island where they established sovereignty over and integrated the existing communities. During periods of conflict with Sakalava in the 17th century and the Kingdom of Imerina in the 19th century, the community periodically sought refuge in the natural stone shelters and caves of the modern Ankarana Reserve, eventually taking their name from the locale and holding it as sacred. In the early 19th century an Antankarana king signed a treaty with French envoys in Reunion that mobilized French troops to expel the Merina from Antankarana territory in exchange for French control over several small islands off Madagascar's west coast. They also aided the French in staging attacks on the Merina monarchy that resulted in the 1896 French colonization of Madagascar. The Antankarana are one of the few communities that continues to honor a single king and reaffirm his sacred ancestral role through traditional ceremonies that date back centuries.

Culturally the Antankarana have many similarities with the neighboring Sakalava. They practice tromba (ancestral spirit possession) and believe in nature spirits. They adhere to a wide range of fady (ancestral taboos), particularly including several that serve to protect wildlife and wilderness areas. The traditional economy of the Antankarana revolved around fishing and livestock, although more recently they have adopted farming; many are salary earners working in civil administration, teaching, trade and other areas.

History

The Antankarana were originally a branch of the Sakalava royal line called the Zafin'i'fotsy (children of silver).[1] This group split off from the Sakalava in the 16th century following a dispute with the Zafin'i'mena (children of gold) that ended with the latter's exclusive right to the kingship.[2] Having been refused the right to the throne, the Zafin'i'fotsy left the Sakalava homeland on the southwestern coast to settle just north of the boundaries of Sakalava control.[1] The first Antankarana king, Kozobe (1614–39), claimed a large part of the island's north as his territory, which he split into five provinces each ruled by one of his sons. This territory was rapidly reduced from the south by Zafin'i'mena prince Andriamandisoarivo, who led violent campaigns into bordering Antankarana territory to expand the frontiers of what was to become the Sakalava Kingdom of Iboina at the end of the 17th century.[2][3] Many Zafin'i'fotsy nobles were killed or quickly surrendered to the advancing Sakalava armies, but oral history celebrates several who resisted, including Andriamanpangy, a descendant of Kozobe.[4] His son Andriantsirotso (1692–1710)[5] founded the Antankarana kingdom, leading the Zafin'i'fotsy further north into the area now protected as Ankarana Reserve and declaring his sovereignty over the north. He was accepted as king both by his own people and by the communities already living in the north, who united together under the name Antankarana (people of the Ankarana rocks). The Sakalava warred with the nascent Antankarana kingdom in its continued effort to claim sovereignty over the territory, but the Antankarana hid themselves in natural shelters formed by the rocks and caves of Ankarana.[4] Eventually they were forced to take refuge at Maroantsetra, a town ruled by a relative named Raholo; Andriantsirotso was able to repel the Sakalava three years later with the support of Raholo's soldiers.[5] Throughout this period Andriantsirotso established the foundations for the kingdom by organizing military cooperation among clans, establishing an administration, developing economic regulations and introducing customs that reinforced a hierarchical social order.[4] According to oral history, at the point when Andriantsirotso was preparing to return to his own capital, a mysterious eight-year-old girl named Tsimatahodrafy arrived in Maroantsetra. She revealed herself to be a sorceress and instructed Andriantsirotso on the rituals to perform en route to ensure his safe return and the establishment of a strong kingdom, including the continuing practice of tying a mat to two tsitakonala trees planted outside the king's house to indicate a royal residence and symbolize the indivisibility of the kingdom.[5]

From its founding, the Antankarana Kingdom was ruled by an unbroken series of nobles of Andriantsirotso's line. He was succeeded by Lamboeny (1710–1790), then Tehimbola (1790–1802), Boanahajy (1802–1809) and Tsialana I (1809–1822).[5] The Kingdom of Imerina rapidly expanded over the first several decades of the 19th century, launching regular military campaigns to bring coastal communities under Merina control. As the Merina neared the Antankarana homeland they established posts along major trade routes where taxes were charged to Antankarana and other merchants, establishing economic control over the territory; this was soon followed by the installation of Merina administrators to govern the territory. Tsialana I was forced to become a vassal of the Merina sovereign.[6] From 1835 to 1837,[4] his son and successor, King Tsimiaro I (1822–1882),[5] made repeated attempts to expel the Merina from his territory, but was unsuccessful.[4] The Merina backlash forced Tsimiaro to lead his people to refuge among the rocks of Ankarana in 1838[7] or 1837, where they lived for over a year.[8] During this time the king was betrayed by one of his own people and the group was surrounded by Merina soldiers. According to oral history, the king prayed for God's help and swore that if they survived, the Antankarana would convert to Islam. Although many of his party were gunned down, the king and most of his subjects escaped to the island of Nosy Mitsio, where they converted; many others were drowned in the attempt to cross. The site of the crossing is most commonly believed to be the village of Ambavan'ankarana, which retains a sacred character and has become a site of pilgrimage and ritual commemoration of the exodus.[9]

In 1838-9 an agreement was signed between the Sakalava king and Seyyid Said, King of Zanzibar, to give Said control over the Sakalava and Antankarana kingdoms; this agreement never came to the attention of Tsimiaro and resulted in no changes in governance on the ground.[10] While in exile on Nosy Mitsio, Tsimiaro traveled to Ile Bourbon to conclude a treaty with the French on 5 April 1841 that guaranteed French protection for the Antankarana in exchange for rights to the islands of Nosy Mitsio, Nosy Faly,[7] Nosy Be and Nosy Komba. The French intercession eventually repelled the Merina, allowing the king to reestablish the capital at Ambatoharaña, but more than 40 years passed before the entire Antankarana had permanently returned to the mainland. Upon his death, Tsimiaro was buried at his request in the Ankarana cave where he had taken refuge from the Merina. Other nobles are mainly entombed in the Islamic cemetery near Ambatoharaña.[11] When the French agreed to recognize Malagasy sovereignty in 1862, they retained their claimed right to the Antankarana and Sakalava protectorates they had established.[12] Tsimiaro was succeeded by his son, Tsialana II, (1883–1924)[5] who was born on Nosy Mitsio in 1843.[11] He collaborated with the French actively during their first expedition against the Merina (1883–85), and again during the successful expedition of 1895 that ended in French colonization of the island and the dismantling of the Merina monarchy.[7] His son Abdourahaman would go on to fight on the side of the French during World War I.[11] Tsialana II was succeeded by Lamboeny II (1925–1938), Tsialana III (1948–1959) and Tsimiharo II (1959–1982).[5]

After Madagascar regained independence from France in 1960 its various administrations interfered little with the reign of Tsimiharo II or his successor Tsimiaro III (1983–current). This changed after the election of Albert Zafy (1991–96), an Antankarana noble from the village of Ambilobe. Zafy sought to reduce the powers of King Tsimiaro III, who responded by "declaring war" against the new president. This standoff came to an end with the election of Zafy's successor, Didier Ratsiraka, who returned to a policy of non-interference in local governance traditions.[13] Tsimiaro III was presumably deposed in 2004 following allegations of corruption, and Lamboeny III was selected to succeed him.[14] However, subsequent conflicts between Tsimiaro III and Lamboeny III have reinstated or maintained Tsimiaro III's position as the de facto King of the Antakarana.[14] He continues to preside over the Antakarana traditional royal ceremonies to this day[15] as well as representing the Antakarana kingdom within Madagascar and abroad.[16]

Identity

There are 50,000 Antakarana in Madagascar as of 2013. They live in the northernmost part of the island, and claim Malagasy and Arab ancestry. They are an offshoot of the Sakalava people.[17] Their territory begins at the northern tip of the island at Antsiranana and extends down the west coast, including the island of Nosy Mitsio. It is bounded to the east by the Bemarivo River and extends south to the village of Tetezambato.[11]

Society

Although subject to all national laws and government, the Antakarana are also united in their recognition of the authority of a king (Ampanjaka) who is the living descendant of a line of Antankarana royalty going back nearly four centuries. The authority of this king is reaffirmed every five years at the village of Ambatoharaña in a ritual mast-raising ceremony called the tsangantsainy. Although some accounts date the ritual back to the origins of Antankarana kingship, the specific features of the ceremony as practiced today are rooted in historical events of the 19th century. The ceremony includes a pilgrimage to Nosy Mitsio to commemorate the flight of Antankarana refugees to the island in the 1830s to escape the advancing armies of the Kingdom of Imerina and to visit the tombs of ancestors who died there; until recently, it has sometimes also included raising both French and Antankarana banners to honor the 1841 treaty signed with the French.[18] The king is selected by a council of elder members of the royal family in the ruling line.[19] He is responsible for reciting joro (ancestral invocations) at ceremonies where the ancestors' blessings are requested.[20] Another important social role is that of the Ndriambavibe. The Antankarana community selects a single noble woman to hold this position, which has similar authority and importance to that of the king.[21] She is not his wife; rather, she has a separate leadership role to fulfill.[20] The Antankarana are recognized among Malagasy as one of the few remaining ethnic groups in Madagascar that continues to reassert the ancestral authority of their king through continued practice of traditional kingship rituals.[22]

Family

Antankarana homes are typically raised on stilts above ground level.[23] Young men seeking to start a family typically leave their father's house and build their own from wood and thatch gathered locally. After marrying a young woman will leave her family's home to move into her husband's house, where she manages the household and assists in planting and harvesting rice. The husband is responsible for earning money for basic necessities and farming the family's land. A young couple typically receives furniture and other essentials as wedding gifts from friends, family and community members. Divorce and remarriage are common in Antankarana society.[24]

Class affiliation

Like elsewhere in Madagascar, Antankarana society was traditionally divided into three classes: nobles, commoners and slaves. Slavery was abolished under the French colonial administration but families often retain their historic affiliations. In traditional communities, descendants of nobles live on the northern side of the village and non-nobles live in the southern part. The areas may be divided by a central clearing where the town hall is often situated; if the village also has a zomba (house reserved for royalty), it would traditionally be located here. Intermarriage across classes is common among the Antankarana, and most can claim a family relation to a member of the noble class.[25] Historically, commoners were further sub-divided into caste-like groups called karazana ("types of people") based on their form of livelihood.[26]

Religious affiliation

The majority of Antankarana identify to varying degrees as Muslim. Once a year at the village of Ambatoharaña, Muslims from across the northern and western parts of Madagascar congregate to visit the tombs of Muslim kings buried here.[27] The form of Islam practiced by the Antankarana is highly syncretic and blends traditional ancestor worship and local customs and beliefs with major holidays and cultural elements borrowed from Arab Muslim culture. The number of Antankarana who practice a standard, orthodox form of Islam is negligible.[11]

Beginning in the late 19th century, the Shādhiliyya Sufi order spread among the Antankarana. According to local traditions, the order was initially spread by Uthmān b. ʿAbd al-Laṭīf, originally from Anjouan. His successors later helped establish the order among the Antankarana and within northern Madagascar.[28]

Culture

Antankarana culture shares many common points with that of their Sakalava neighbors. Their rituals are similar and honor many of the same ancestors, and members of both groups adhere to many of the same fady, making it difficult at times to distinguish the two groups from one another. Relations between the two are amicable.[1] In a custom unique to the Antankarana, called the tsangatsaine, two trees growing before the house of a noble family are tied together to symbolize the unity of the community. and the merger of past with present and the dead with the living.[29] The Antankarana, like many other coastal groups, practice tromba (spirit possession) as a means to commune with ancestors. The royal ancestral spirits that possess tromba mediums are almost always of Sakalava ancestry.[30] It is widely believed that the spirits of the dead often inhabit crocodiles, and it is often fady among the Antankarana to kill these animals.[31] The Antankarana also believe in tsiny, a kind of nature spirit.[32]

Rice is the foundation of every meal, and is often eaten with fish broth, greens, beans or squash. Manioc and green bananas are staples most commonly eaten when other, preferred, foods are too expensive or out of season.[33] The Antankarana were historically herders and although they are now generally agriculturalists, cattle are kept for milk. They are also viewed as a form of wealth; the number of cattle one gives away indicates generosity, and the number sacrificed to the ancestors is a measure of loyalty. The sacrifice of zebu is a typical element of many major rituals and celebrations ranging from Muslim holidays to life events like marriage, death and birth.[34]

The traditional martial art of Madagascar, moraingy, and large dance parties (baly) are very popular among the Antankarana youth, who often are drawn more to western culture than ancestral practices and beliefs.[34]

Clothing was historically made from woven raffia. The fibers would be combed into strands that were knotted together to form cords, which were then woven into panels. These panels were stitched together to create prayer rugs and clothing. Women and men historically wore long raffia smocks.[35]

Fady

Numerous fady protect wilderness areas, particularly including the Ankarana massif.[9] Excessive cutting of mangrove trees for wood or the setting of bush fires are both prohibited, as is the use of nets with holes less than 15 millimeters to prevent catching immature fish.[36] Certain species are protected through fady that forbid hunting them, including sharks, rays and crocodiles.[37] Many fady also exist to regulate relations between the sexes. For instance, it is taboo for a girl to wash her own brother's clothing.[23] Conservative communities adhere to a fady against medical injections, surgery or modern medicines due to their association with their historic enemies the Merina, who were the first to use them widely; instead, tromba ceremonies and traditional herbal remedies are commonly used for healing.[32] These taboos are most strongly applied in the center of Antankarana territory around the village of Ambatoharaña and less so in the villages at the periphery of the region.[38]

Funeral rites

Funerals among the Antankarana are often celebratory events. Among villagers living near the sea, it is not uncommon for the remains of a loved one to be placed in a coffin which the family carries running into the sea.[39]

Dance and music

At royal ceremonies a traditional dance called the rabiky is often performed.[1]

Language

The Antankarana speak a dialect of the Malagasy language, which is a branch of the Malayo-Polynesian language group derived from the Barito languages, spoken in southern Borneo.[40]

Economy

The Antankarana were historically fishermen and pastoralist zebu herders, although in recent years most have become agriculturalists.[23] Sea fishing is carried out in two-man canoes made from a single hollowed out log.[41] Antankarana fishermen used these canoes to hunt whales, turtles and fish. They also used nets to hunt in rivers, where they could catch eels, fish, crayfish and other food sources.[42] Salt production was historically a major economic activity.[43] Historically the Antankarana engaged in trading with European seafarers, exchanging tortoiseshell for guns.[44] Today, while the majority of Antankarana continue to work in these traditional sectors – especially the highly lucrative shrimp fishing business or the growing of sugarcane – many are wage laborers. More highly educated community members, particularly among the noble class, work in salaried positions as government officials, teachers and a variety of other trades and professions. The SIRAMA national sugar company factories are located in Antankarana territory and employ many migrants, but relatively few Antankarana as their standard of living on average is high enough to be able to pursue better opportunities.[45]

The most significant urban area in the Antankarana homeland is Antsiranana (formerly Diego-Suarez).[23] Ambilobe, where the current king resides. is the nearest major urban area to the traditional seat of royal Antankarana power at Ambatoharaña.[45]

Notes

- Sharp 1993, p. 78.

- Giguère 2006, p. 21.

- Gezon 2006, p. 68.

- Giguère 2006, p. 22.

- Tsitindry, Jeanne-Baptistine (1987). "Navian'ny tsangan-tsainy" (PDF). Omaly Sy Anio (in French). 25–26: 31–40. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Middleton 1999, p. 169.

- Campbell 2012, p. 832.

- Middleton 1999, p. 147.

- Giguère 2006, p. 23.

- Campbell 2005, p. 343.

- Middleton 1999, p. 148.

- Boahen 1990, p. 108.

- Giguère 2006, p. 43.

- Carayol, Rémi (30 November 2009). "Madagascar: Les princes aussi connaissent la crise". Jeune Afrique (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "Diana-Sava – Deux clans sakalava réconciliés à Maromokotra". L'Express de Madagascar - Actualités en direct sur Madagascar (in French). 2016-11-16. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- "Premier congrès des chefs traditionnels d'Afrique - Madagascar-Tribune.com". www.madagascar-tribune.com (in French). Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- Diagram Group 2013.

- Walsh 1998, p. 1.

- Walsh 1998, p. 64.

- Walsh 1998, p. 67.

- Walsh 1998, pp. 33–34.

- Middleton 1999, p. 167.

- Bradt & Austin 2007, p. 23.

- Walsh 1998, p. 36.

- Walsh 1998, pp. 31–32.

- Middleton 1999, p. 20.

- Walsh 1998, p. 34.

- Bang, Anne K. (2014), "The Shādhiliyya in Northern Madagascar c. 1890–1940: The Planting of a Garden and the Growing of Malagasy Roots", Islamic Sufi Networks in the Western Indian Ocean (c.1880-1940), BRILL, pp. 72–89, doi:10.1163/9789004276543_005, retrieved 2022-08-11

- Bradt & Austin 2007, p. 22.

- Sharp 1993, p. 178.

- Campbell 2012, p. 472.

- Giguère 2006, p. 84.

- Walsh 1998, p. 37.

- Walsh 1998, p. 40.

- Condra 2013, p. 455.

- Giguère 2006, p. 85.

- Giguère 2006, p. 83.

- Middleton 1999, p. 156.

- Bradt & Austin 2007, pp. 16–17.

- Ferrand 1902, p. 12.

- Campbell 2005, p. 38.

- Campbell 2005, p. 30.

- Campbell 2012, p. 455.

- Campbell 2005, p. 55.

- Middleton 1999, p. 154.

Bibliography

- Boahen, A. Adu (1990). Africa Under Colonial Domination, 1880–1935. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520067028.

- Bradt, Hilary; Austin, Daniel (2007). Madagascar (9th ed.). Guilford, CT: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. ISBN 978-1-84162-197-5.

- Campbell, Gwyn (2012). David Griffiths and the Missionary "History of Madagascar". Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9789004209800.

- Campbell, Gwyn (2005). An Economic History of Imperial Madagascar, 1750–1895: The Rise and Fall of an Island Empire. Cambridge MA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521839358.

- Condra, Jill (2013). Encyclopedia of National Dress: Traditional Clothing Around the World. Los Angeles: ABC Clio. ISBN 978-0-313-37637-5.

- Diagram Group (2013). Encyclopedia of African Peoples. San Francisco, CA: Routledge. ISBN 9781135963415.

- Ferrand, Gabriel (1902). Les musulmans a Madagascar et aux Comores: Troisieme partie – Antankarana, sakalava, migrations arabes (in French). Paris: Ernest Leroux. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Gezon, Lisa L. (2006). Global Visions, Local Landscapes: A Political Ecology of Conservation, Conflict, and Control in Northern Madagascar. Lanham, MD: Rowman Altamira. ISBN 9780759114104.

- Giguère, Hélène (2006). Des morts, des vivants et des choses: ethnographie d'un village de pêcheurs au nord de Madagascar (in French). Paris: Presses Université Laval. ISBN 9782763783246.

- Middleton, Karen (1999). Ancestors, Power, and History in Madagascar. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9789004112896.

- Sharp, Lesley (1993). The Possessed and the Dispossessed: Spirits, Identity, and Power in a Madagascar Migrant Town. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520918450.

- Walsh, Andrew (1998). Constructing Antankaraña, history, ritual and identity in northern Madagascar (PDF). Toronto: National Library of Canada.