Antoine Hamilton

Anthony Hamilton PC (Ire) (c. 1645 – 1719), also known as Antoine[lower-alpha 1] and comte d'Hamilton, was a soldier and a writer. As a Catholic of Irish and Scottish ancestry, his parents brought him to France as a child in 1651 when Cromwell's army overran Ireland.

Anthony Hamilton | |

|---|---|

Detail from the portrait below | |

| Born | 1644 or 1645 Ireland, probably Nenagh |

| Died | 21 April 1719 Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France |

| Father | George Hamilton, 1st Baronet |

| Mother | Mary Butler |

At the Restoration the family moved to England and lived at the court of Charles II. When Catholics were excluded from the army, Anthony followed his brother George into French service and fought in the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678). After the accession of the Catholic king James II in 1685, he joined the Irish Army and fought for James in the Williamite War (1689–1691). He saw action in the battles of Newtownbutler and the Boyne. The defeat led him to his final French exile.

Hamilton sought refuge at the Jacobite court at Saint-Germain-en-Laye where he became a courtier, poet, and writer. He chose French as his language and adopted a light and elegant style, seeking to amuse and entertain his reader. He is known for the Mémoires du Comte de Grammont, which focus on the time his brother-in-law Philibert de Gramont, spent at the court of Charles II. These Mémoires are a classic of French literature and a document of the history of the Stuart Restoration. He also wrote many letters, poems, and five tales.

| Family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Birth and origins

Anthony was born in 1644 or 1645[lower-alpha 3] in Ireland, probably in Nenagh (/ˈniːnæ/)[11], County Tipperary.[lower-alpha 4] He was the third son of George Hamilton and his wife Mary Butler.[20]

His father was Scottish, the fourth son of James Hamilton, 1st Earl of Abercorn.[21] He supported the lord lieutenant of Ireland, James Butler, Marquess of Ormond,[22][23] during the Irish Confederate Wars and the Cromwellian conquest[24] and called himself a baronet.[25][26][lower-alpha 5]

Anthony's mother was Irish, the third daughter of Thomas Butler, Viscount Thurles (courtesy title), who predeceased his father, Walter Butler, 11th Earl of Ormond, and therefore never succeeded to the earldom.[27] She also was a sister of James Butler,[28] making her husband a brother-in-law of the lord lieutenant.[22][24] Her family, the Butlers, were Old English.[29]

Anthony's father has been confused with his granduncle George Hamilton of Greenlaw and Roscrea. Both are called George and both married a Mary Butler.[5] In 1640 Ormond had granted Anthony's father Nenagh for 31 years.[30] Anthony was probably born there,[12] despite some giving Roscrea,[15][16][17][7][31][18] where the granduncle lived.[5] Hamilton's parents had married in 1635,[32] despite earlier dates reported in error,[33][34][35] due to the mistaken identity.[lower-alpha 6]

Anthony was one of nine siblings.[20][36] See James, George, Elizabeth, Richard, and John.[lower-alpha 7] Anthony's parents were both Catholic,[lower-alpha 8] and so was he.[37][38]

Irish childhood

Hamilton was born during the Irish Confederate War. His father, despite being Catholic,[39] sided with the lord lieutenant against the Confederates.[40][41] The war had been halted by a truce in 1643,[42] and was believed to have ended when the first Ormond peace was signed in March 1646.[43] However, strong opposition to the peace from the Catholic Church caused the Confederates to split into a clerical and a peace faction.[44] In May, Lady Hamilton, with Anthony and his siblings, left Nenagh and was brought to Dublin for her security.[45] In August the Papal Nuncio Rinuccini rejected the first Ormond peace.[46] In September the Confederate Ulster army, in support of the clerical faction, took Roscrea,[47] where Hamilton's aunt (not his mother despite contrary opinions)[47][48] was living.[49]

In January 1647 Hamilton's father returned to Dublin from a mission to the king for Ormond. He brought secret instructions directing Ormond to hand Dublin over to the English rather than to the Irish when the need came.[50] Ormond therefore abandoned Dublin to Michael Jones in July and left for England.[51] Little Anthony, his mother and siblings seemed to have stayed behind in Ireland until 1651.[52]

In summer 1648, Ulster troops stormed Nenagh,[53] but Inchiquin with his Protestant Munster army soon retook the town for the king.[54] Anthony, his mother, and siblings avoided both these dangers by having been removed to Dublin.[45] In August Hamilton's father was at Queen Henrietta Maria's exile court,[55] preparing Ormond's return to Ireland in September.[56]

In 1649, during the Cromwellian conquest, Ormond made Hamilton's father receiver-general of the revenues[57] and governor of Nenagh Castle,[58] which he tried to defend against Henry Ireton in November 1650.[59]

First French exile

Having lost the leadership to the Catholic clergy,[60] Ormond left for France in December 1650.[61] Hamilton's father could not leave with him as he was accused of fraud by the clergy.[62] Found innocent, he left Ireland, accompanied by his family, in spring 1651. Anthony, his mother and siblings, seem to have stayed in Ireland until then.[52] Anthony was about seven. They went to Caen, Normandy,[63] where they were accommodated for some time by Anthony's aunt Elizabeth Preston, the Marchioness of Ormond.[64][65] His father and his elder brothers, James and George, served Charles II in various functions.[66][67] Lady Ormond with her children left for England in August 1652,[68] whereas Anthony's mother moved to Paris, where she lived in the Convent of the Feuillantines.[69] The Hamilton brothers frequented the court of the young Charles II and his mother, Henrietta Maria, the dowager queen, at the Louvre.[70]

Restoration

In May 1660 the Restoration brought Charles II on the English throne.[71] Anthony's father and his elder sons moved to the court at Whitehall.[72] Charles II restored Donalong, Ulster, to Hamilton's father.[73] About that year Charles allegedly created Hamilton's father baronet of Donalong and Nenagh,[lower-alpha 5] but the king, if he really went that far, refused to go further because the family was Catholic.[74]

Anthony's elder brothers, James and George, became courtiers at Whitehall.[76] In 1661 the King helped to arrange a Protestant marriage for James.[77][78][79] Early in 1661 Anthony's father also brought his wife and younger children to London,[80] where they lived for some time all together in a house near Whitehall.[81]

In January 1663 at Whitehall, the Hamilton brothers met Philibert, chevalier de Gramont,[70] a French exile,[82] who had got into trouble by courting a maid of honour, on whom Louis XIV had set his eyes.[83][84][85]

Gramont had no difficulties to integrate as French was spoken at the court.[86][lower-alpha 10] Anthony befriended Gramont,[88] who soon became part of the inner circle.[89] Gramont courted Anthony's sister Elizabeth.[90][91]

A famous anecdote tells how George and Anthony pursued and intercepted Gramont at Dover, asking him whether he had not forgotten something in London.[92] He replied "Pardonnez-moi, messieurs, j'ai oublié d'épouser votre sœur." (Forgive me, Sirs, I have forgotten to marry your sister).[93][94] This episode might have happened in autumn 1663 when Gramont's sister Susanne-Charlotte, the Marchioness of Saint-Chaumont,[95] told him that he could return to France.[96][97] He goes there but finds that she was mistaken.[98] But perhaps it rather happened in December just before he made public his intention to marry her.[99]

He married Elizabeth in London, either in December 1663 or early in 1664.[100][101][102] In March 1664, Louis XIV, having heard of Gramont's marriage, allowed him to return.[103]

Second French exile

In 1667, Anthony's brother George refused to take the oath of supremacy and went to France.[104] It seems that Anthony went with him.[105] In 1671 George recruited a regiment in Ireland for French service.[106] Anthony seems to have been with him and helped his cousin John Butler to save Dublin Castle from destruction by fire.[107][108] Anthony then took service in that regiment, fighting in the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678).[109] They were later joined by Anthony's younger brother Richard.[110] In 1672, the desastrous "rampjaar" of the Dutch, the regiment garrisoned Liège[111] and then helped to besiege Utrecht.[112] In 1673 Captain Anthony was in Limerick recruiting for the regiment.[113]

Anthony probably fought together with George under Turenne against German imperial troops in the Battle of Sinsheim in June 1674, and did surely so at Entzheim in October,[115] where both were wounded.[116] In the winter 1674/5 Anthony, together with George and Richard, travelled to England from where George returned to France while Anthony and Richard continued to Ireland to recruit.[117] French ships picked up the recruits at Kinsale in April 1675[118] after a missed appointment at Dingle in March.[119]

Anthony's Irish voyage caused him to miss Turenne's winter campaign in which the French marched south and surprised the Germans in upper Alsace, beating them at Turckheim in January 1675.[120]

In July 1675 Hamilton's regiment was at Sasbach, where George witnessed Turenne's death.[121] At the retreat from Sasbach in August, the regiment suffered 450 casualties in the rearguard actions of the Battle of Altenheim.[122] Condé was called in and stopped the German advance,[123][124] but he retired from service at the end of the campaign.[125] In the winter 1675/6 George, accompanied by either Anthony or Richard, again went recruiting[126] and visited Lady Arran, wife of Richard Butler, 1st Earl of Arran, in January 1676. She called them "ye monsieurs".[127] The regiment passed that winter in Toul.[126]

Luxembourg commanded on the Rhine in the campaign of 1676.[128] In June George was killed while commanding the rearguard at the Zaberner Steige (Col de Saverne) where imperial troops under the Duke of Lorraine pursued the French who were retreating eastward to Zabern (Saverne) in lower Alsace.[129][130] Reputedly, Anthony succeeded his brother as comte d'Hamilton,[131] but that title may never have existed.[132][133][lower-alpha 11] Thomas Dongan, who had been lieutenant-colonel, was preferred over Anthony as the new colonel of what had been Hamilton's regiment.[141] Louis XIV told Anthony that he had no regiment for him.[142] Anthony left[137][143] while Richard became lieutenant-colonel.[144] In August 1678 the Peace of Nijmegen ended the Franco-Dutch War.[145] The regiment was disbanded in December.[146]

Ireland

Hamilton lived in Ireland from 1677 to 1684.[147] His father died in 1679.[28] His nephew James Hamilton, the future 6th Earl of Abercorn, then aged 17 or 18, inherited the family's lands.[148] In summer 1681 Anthony lived in Dublin.[149]

He may have visited France in 1681 and have been the "comte d'Hamilton" who played one of six zephyrs needed in the performance of Quinault's ballet the Triomphe de l'Amour, to music by Lully, at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye before Louis XIV.[134][150][151][152] However, it could also have been Richard.[153][154]

In February 1685 the Catholic James II acceded to the English throne.[155] In April James sent Richard Talbot to Ireland to purge the Irish army of "Cromwellians".[156] Talbot replaced Protestants with Catholics,[157] recruiting among others Anthony and his younger brothers Richard and John.[158][159] Anthony was appointed lieutenant-colonel of Sir Thomas Newcomen's infantry regiment.[160] In June James created Talbot earl of Tyrconnell.[161] In August Hamilton was also made governor of Limerick, where Newcomen's regiment was garrisoned, replacing Sir William King, a Protestant.[162][163] Hamilton attended Mass in public.[164][165] In October 1685 the king appointed Henry Hyde, 2nd Earl of Clarendon, a Protestant, as lord lieutenant of Ireland. Clarendon arrived in Dublin in January 1686. He considered Hamilton a moderate Catholic and possible ally. Clarendon praised Hamilton saying that he understood the regiment better than its colonel.[166] He also stated that Hamilton objected to replacing efficient Protestant officers with Catholic ones of a lesser merit.[167] At the end of 1686 Hamilton was sworn of the Irish privy council.[168][169] In 1687 he was promoted colonel.[170] In 1688 Hamilton is mentioned as the colonel of a regiment of foot.[171]

At the eve of the Glorious Revolution in late September 1688, James asked Tyrconnell to send four Irish regiments to England.[172] Hamilton's was among them.[173][174] The troops landed on the English west coast in October and marched across the midlands to southern England.[175] Hamilton's regiment was stationed in Portsmouth, where the Duke of Berwick was governor.[176] The regiment surrendered in Portsmouth on 20 December.[177][lower-alpha 12] On the 23rd James II embarked for France.[179] It seems that Hamilton followed him. Anthony and John[180] returned with James II to Ireland[181] in 1689.[182] Richard was already there having been trusted with a diplomatic mission to Tyrconnell by William.[183]

In 1689 during the Williamite War, Tyrconnell promoted Hamilton major-general[184] and gave him the command of the dragoons of an army under Justin McCarthy, Viscount Mountcashel, that he sent north to Belturbet,[185] County Cavan, to fight the rebels of Enniskillen. In the battle of Newtownbutler, in July, Hamilton commanded the horse. The outcome would show that he was "better with his pen than with his sword".[186] Mountcashel asked him to pursue retreating enemy troops[187], but the enemy led him into a trap and Hamilton's dragoons were routed.[188] Hamilton was wounded in the leg at the beginning of the action[189] and fled the scene.[190] With Captain Peter Lavallin of Carroll's dragoons[191] he was court martialled by de Rosen. Given his family's influence, Hamilton was acquitted, but Lavallin was shot.[192] This affair destroyed Hamilton's reputation as a soldier. When in spring 1690 the Irish Brigade was formed,[193] the French insisted that neither Richard nor Anthony should be among its officers.[194]

Hamilton rode in the cavalry charges at the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690.[195] He also helped to defend Limerick at its first siege of the war.[196] When William raised this siege end of August,[197] Tyrconnell sent Hamilton to France to report the deliverance.[198] He does not seem to have returned and seems to have been absent from the Battle of Aughrim[199] in 1691, where his youngest brother, John, was fatally wounded.[200][201]

Final French exile, death, and timeline

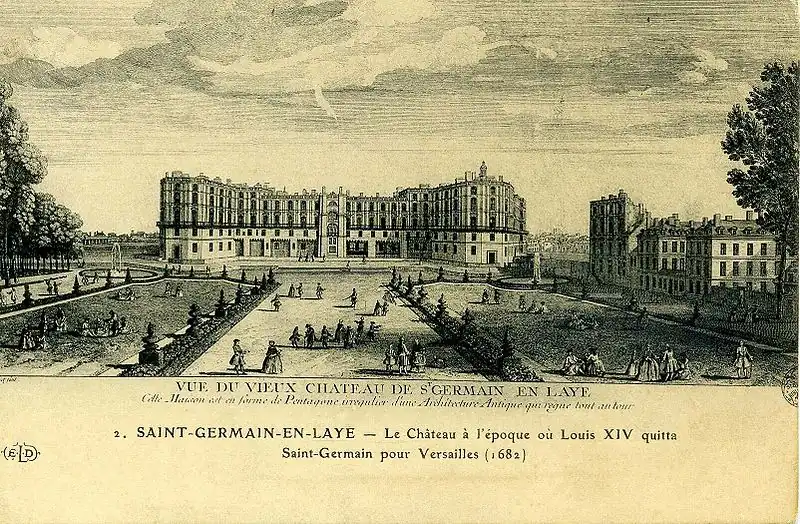

Hamilton spent most of the last thirty years of his life at the exile court at the Château-vieux of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[202][203][lower-alpha 13] He held no office,[205] but James II gave him a generous pension.[206][lower-alpha 14] The king also lent him an apartment in the castle.[211] Hamilton was appreciated as an ornament of that court.[212]

At Saint-Germain Hamilton got acquainted with the Bulkeley sisters, especially Anne and Henrietta.[215] Their father, Henry Bulkeley, Master of the Household for Charles II and James II at Whitehall and at Saint-Germain, died in 1698.[216] Their mother, Sophia, was a sister of the Belle Stuart.[217] Hamilton called Anne "Nanette".[218] Berwick married her in 1700 at Saint-Germain, as his second wife.[219][220] Hamilton was in love with Henrietta or at least wrote admirative letters to her.[221] She was about 30 years younger than him and had no dowry.[lower-alpha 16] Hamilton thought his pension insufficient to support a family.[222]

In 1695 Hamilton wrote his tale Zénéyde,[lower-alpha 17] in which he complains about the oppressive religiosity of James's last years.[226] Early in 1701 Hamilton accompanied Berwick on a mission to Rome to ask the new pope, Clement XI, to support the Jacobites.[227] In March James suffered a stroke.[228] Berwick was called for and arrived back in Saint-Germain in April.[229] In September James II died at the Château-vieux of Saint-Germain.[230][231] Hamilton wrote a poem about his death, "Sur l'agonie du feu roi d'Angleterre".[232] In 1703 Louis XIV gave Hamilton's sister Elizabeth a house at the end of the park of the Château de Versailles, where Hamilton often visited.[233][234] In 1704 Hamilton went to see Gramont at Séméac in Gascogne, where he decided to write his friend's memoirs.[235]

Hamilton was part of the circle around the Duchess of Maine,[236] where he was known as "Horace d'Albion".[237] It was partly at her seat at Sceaux that he wrote the Mémoires that made him famous.[238] He attended the feast in August 1705 that the duchess gave together with Nicolas de Malézieu at Châtenay.[239]

In 1707 Gramont died in Paris.[240][241][242][lower-alpha 18] Hamilton was said to have sailed to Scotland in the attempted invasion[243][244] in March 1708, but only Richard went.[245] In June Hamilton's sister Elizabeth died in Paris.[246][247]

In summer 1712, James III, the Old Pretender, left Saint-Germain as France was about to drop the Jacobites, a concession they made in 1713 at the Peace of Utrecht.[248] Richard followed James III to Bar-le-Duc in Lorraine,[249] whereas Anthony stayed behind at Saint-Germain and was allowed to keep his apartment.[211] The dowager queen, Mary of Modena, also stayed behind.[250] Hamilton met the young Voltaire at the suppers of the Society of the Temple shortly before 1715.[251][lower-alpha 19]

Hamilton never married and died at Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 20 April 1719.[lower-alpha 20] He was buried on the 21st in the parish church.[139]

| Timeline | ||

|---|---|---|

| As his birth date is uncertain, so are all his ages. Italics for historical background. | ||

| Age | Date | Event |

| 0 | 1644 or 1645 | Born,[lower-alpha 3] probably at Nenagh in Ireland[lower-alpha 4] |

| 1 | May 1646 | Moved to Dublin with his mother.[45] |

| 1 | 17 Sep 1646 | Owen Roe O'Neill took Roscrea.[47] |

| 2 | 28 Jul 1647 | Ormond abandoned Dublin to the Parliamentarians.[51] |

| 3 | 13 Nov 1647 | Battle of Knocknanuss, the Confederates were beaten by Inchiquin.[262] |

| 3 | 29 Sep 1648 | Ormond returned to Ireland landing at Cork.[56] |

| 4 | 30 Jan 1649 | Charles I beheaded[263] |

| 4 | 2 Aug 1649 | Battle of Rathmines. Michael Jones defeated Ormond before Dublin.[264] |

| 5–6 | Oct 1650 | Father defended Nenagh Castle against the Parliamentarians.[59] |

| 6 | 7 Dec 1650 | James Butler, Marquess of Ormond left Ireland.[61] |

| 6–7 | Early in 1651 | Taken to France by his parents[52] |

| 15 | 29 May 1660 | Restoration of Charles II[71] |

| 15–16 | 1660 | Followed Charles II to England[265] |

| 18 | 15 Jan 1663 | The chevalier de Gramont arrived in London;[70] |

| 19 | 1663/1664 | Sister Elizabeth married Gramont.[101][100] |

| 26–27 | 1671 | Brother George raised an Irish regiment for French service.[106] |

| 28 | Jun 1673 | Brother James fatally wounded in a sea-fight against the Dutch[266] |

| 29–30 | 6 Oct 1674 | Wounded at the Battle of Entzheim[116] |

| 30–31 | 1675 | Travelled to Ireland to recruit[117] |

| 31–32 | 1676 | Brother George killed at the Col de Saverne[130] |

| 33–34 | 1678 | Supposedly succeeded his brother George as "comte d'Hamilton"[131] |

| 34–35 | 26 Jan 1679 | Treaties of Nijmegen ended the Franco-Dutch War between France and the Empire.[145] |

| 34–35 | 1679 | Father died.[28] |

| 35 | Aug 1680 | Mother died.[28] |

| 40 | 6 Feb 1685 | Accession of James II, succeeding Charles II[155] |

| 40 | 24 Feb 1685 | Boyle & Granard appointed lords justices replacing Ormond, lord lieutenant[267] |

| 40–41 | 1685 | Took service in the Irish army as lieutenant-colonel.[160] |

| 40 | 1 Aug 1685 | Made governor of Limerick[165] |

| 40–41 | 1 Oct 1685 | Henry Hyde, 2nd Earl of Clarendon appointed lord lieutenant of Ireland[268] |

| 42 | 8 Jan 1687 | Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, appointed lord deputy of Ireland[269] |

| 43–44 | 1688 | His regiment sent to England to protect James II[173] |

| 44 | 13 Feb 1689 | Accession of William and Mary, succeeding James II[270] |

| 44 | 12 Mar 1689 | King James II landed at Kinsale, Ireland[182] |

| 44 | 31 Jul 1689 | Defeated at Newtownbutler[189] |

| 45 | 1 Jul 1690 | Fought at the Battle of the Boyne[195] |

| 45–46 | Autumn 1690 | Went to France to report the raise of the Siege of Limerick[198] |

| 56 | 16 Sep 1701 | James II died at Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[230] |

| 59–60 | 1704 | Started writing the Mémoires du comte de Grammont.[235] |

| 62 | 30 Jan 1707 | Friend Gramont died in Paris.[241][242][240] |

| 63 | Mar 1708 | Said to have taken part in the attempted invasion, but only Richard went.[245] |

| 63 | 3 Jun 1708 | Sister Elizabeth died in Paris.[246][247] |

| 68 | 11 Apr 1713 | Peace of Utrecht ended the War of the Spanish Succession;[248] |

| 68–69 | 1713 | Gramont's Memoirs published anonymously[271] |

| 69 | 1 Aug 1714 | Accession of George I, succeeding Anne[272] |

| 70 | 1 Sep 1715 | Death of Louis XIV; Regency until the majority of Louis XV[273] |

| 71 | 22 Dec 1715 | James III landed in Scotland during the Jacobite rising of 1715.[274] |

| 74 | 20 Apr 1719 | Died at Saint-Germain-en-Laye[6] |

Works

Hamilton came from an English-speaking family[lower-alpha 21] but chose to write in French. People often wonder how a foreigner could write French so well and excel in that light and elegant badinage considered so typically French.[275]

Hamilton was a well known author in the 18th century. Voltaire and La Harpe mention him honourably.[276][19][277] Today, Hamilton is mainly known for a single book: the Mémoires de la vie du comte de Grammont,[278] the only work published while he was alive. Horace Walpole was an admirer of Gramont's memoirs.[279] Hamilton also wrote at least five tales and many poems, songs, epistles, and letters. The following works might be worthwhile mentioning (ordered by year of publication):

- 1713 Mémoires de la vie du comte de Grammont [Memoirs of the Life of Count Grammont] (Cologne: Pierre Marteau), read online in French or English

- 1730 Le Bélier [The Ram] (Paris: Josse), read online in French or English

- 1730 Histoire de Fleur d'Epine [Thornflower Story] (Paris: Josse), read online in French or English

- 1730 Quatre Facardins [Four Facardins] (Paris: Josse), read online in French or English

- 1731 in Œuvres mêlées en prose et en vers [Miscellaneous works in prose and verse] (Paris: Josse):

- De l'usage de la vie dans la vieillesse [Of the use of life in old age], p. 63 of Poésies [Poems], read online

- Sur l'agonie du feu roi d'Angleterre [On the Agony of the King of England], p. 66 of Poésies [Poems], read online

- Epistle à monsieur le comte de Grammont [Epistle to Count Gramont], p. 1 of Epitres et lettres, read online in French or English

- Zénéyde, read online in French or English

- 1776 L'Enchanteur Faustus [The Enchanter Faustus],[280] read online in French or English

Grammont's memoirs

The Mémoires de la vie du comte de Gramont were originally planned to cover Gramont's entire life but were cut short so that they end with his marriage. Hamilton pretended the memoirs were dictated to him by Gramont.[281] He started work on the memoirs in 1704 and completed them in 1710.[235][282] For Gramont's life up to his arrival in London in January 1663,[70] Gramont was Hamilton's only source. This first part of the memoirs may have been jotted down in a form quite similar to how Gramont told it.[283][284] The second, "English", part seems to be more Hamilton's work.[285] The subtitle of the first edition "L'histore amoureuse de la cour d'Angleterre" (lovelife of the English court) pertains to this part, for which Hamilton had Gramont, who died in 1707, and also Elizabeth, who died in 1708, as witnesses.[286] Hamilton's brothers James and George, important characters of the second part, had died in 1673 and in 1676 respectively.[287][129]

The book was a bestseller of its time[288][289] and is a classic and a masterpiece of French literature.[290][291] It is still admired for its graceful and elegant French.[292] The memoirs were written to amuse and entertain the reader and sometimes depart from the correct chronological order.[293] They situate themselves at the cross-roads between memoirs, biography, and fiction.[294]

The memoirs were first circulated in manuscript[295] and then published anonymously in 1713, apparently without Hamilton's knowledge. The imprint says: Cologne by "Pierre Marteau", a pseudonym often used for books forbidden by the censors.[296] The real publisher might have been hiding in Holland,[297] or at Rouen.[298] In 1817 the Catholic Church inscribed the book on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.[299] Early French editions often deformed the English names. Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill Press edition of 1772 corrected them.[300]

The first English translation, by Abel Boyer, had followed in hot pursuit in 1714.[301] In this edition Boyer, fearing an uproar, hid the persons' identities behind their initials.[302] Many new or amended English translations of the Memoirs were published in due course. W. Maddison published one in 1793.[303][304][305] Walter Scott amended an English translation in 1809 and again in 1811.[306] Henry Vizetelly published another revised translation in 1889.[307] Peter Quennell retranslated the Memoirs in 1930. This translation was prefaced and annotated by Cyril Hughes Hartmann.[308]

Tales

Hamilton's tales (contes) were inspired by Charles Perrault's fairy tales,[309] published in 1697,[310] and by Antoine Galland's Arabian Nights, published between 1704 and 1708.[311] Hamilton's tales are their parodies or fan fiction.[312] They play in fantasy worlds with fairy-tale or orientalist accessories. The characters' adventures are often surrealistic, absurd, difficult to understand, or do not make sense beyond surprise and entertainment.[313] However, George Saintsbury maintains that Hamilton's tales are superior to the Memoirs with regard to their literary merit.[314] Hamilton left Zénéyde and Les quatre Facardins incomplete. Several completions for them have been invented, best known are those by the Duc de Lévis, written in 1812.[315]

Zénéyde, written in 1695,[lower-alpha 17] starts as a letter to "Madame de P.", in which Hamilton complains about James II's exile court and then escapes into a fancy world by meeting a nymph at the Seine.[316] The bulk of the story is told by the nymph, called Zénéyde. She tells him her life or at least her origins, as the author has left the story incomplete. She explains that her father was the Roman emperor Maximus and her mother a daughter of the Frankish king Clodio. She goes on to say how she was promised in marriage to Childeric but then taken prisoner by Genserich at Aquileia and brought to Africa. Hamilton's story breaks off here.[lower-alpha 22]

Le Bélier, written in 1705,[317] pretends to give an etymology for "Pontalie",[318] the name his sister Elizabeth invented for Les Moulineaux, her house at Versailles.[319][320] The story starts in verse and then continues in prose. It tells of a giant called Moulineaux, who has an ingenious ram, and of his neighbour, a druide, who has a beautiful daughter called Alie. The giant wants to marry Alie but her father protects her by surrounding his castle with a river. The ram builds a bridge across it. This is Alie's bridge, or Pont-Alie. The Prince of Noisy is called in for help. Bélier is full of comical and absurd inventions.[321] The exhortion, "Belier, mon ami, tu me ferais plaisir si tu voulais commencer par le commencement," became a proverb.[322] Voltaire mentioned in 1729 that Josse was printing the Bélier.[323] It was the first of Hamilton's tales to be published and must have been a success as Josse went on to publish two more of Hamilton's tales and the first collection of his works, Œuvres mêlées en prose et en vers.

Hamilton wrote Fleur d'Épine and Les quatre Facardins in imitation and parody of Arabian Nights.[324][325] Fleur d'Épine is started in the thousand-and-first night, whereas Les quatre Facardins is started in the thousand-and-second night.[326]

Fleur d'Épine tells us how a page called "Tarare" saves the eponymous main character from the clutches of a sorceress.[327] It has been praised by La Harpe for its charming truths and its moral.[328]

Les quatre Facardins tells of the adventures of four men all called Facardin. Despite having left incomplete by its author, Saintsbury considers it the best of Hamilton's tales.[329]

L'Enchanteur Faustus tells how Faust conjures up Helen of Troy, Cleopatra, Fair Rosamond, and other beauties to appear before Queen Elizabeth of England.[330] Contrary to Hamilton's other tales, this one is linear and easy to follow.[331] Hamilton dedicated it to his niece Margaret, his brother John's daughter.[332]

Hamilton's tales were circulated privately as manuscripts during his lifetime.[295] The first three were published individually in Paris in 1730, ten years after the author's death. A collection of his works, Œuvres mêlées en prose et en vers, published in 1731, contains the unfinished Zénéyde.[333] L'Enchanteur Faustus was published belatedly in 1776[280] but might have been written much earlier, probably even before the Memoirs.[334]

Other works

Hamilton also wrote songs and exchanged amusing verses with the Duke of Berwick.[335] He helped his niece Claude Charlotte, Gramont's daughter, who had married Henry Stafford-Howard, 1st Earl of Stafford, in 1694,[336] to carry on a witty correspondence with Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.[337][338]

Notes and references

Notes

- Ó Ciardha (2009) gives Antoine in parentheses after Anthony.[12] French sources usually call him "Antoine Hamilton".[8][339][340][341]

- This family tree is partly derived from the Abercorn pedigree pictured in Cokayne[1] and written genealogies of the Abercorns.[2][3]

- Anthony Hamilton died on the 20 April 1719 aged 74.[6] He was therefore born between 21 April 1644 and 20 April 1645.[7] Older authors in error give his year of death as 1720, leading to a later date of birth (i.e. 1645 or 1646).[8][9] Walter Scott (1846) proposes an earlier date but stays vague.[10]

- Ó Ciardha (2009), Manning (2001), and Gleeson (1947) say Hamilton might have been born at Nenagh.[12][13][14] However, most older authors give Roscrea because they confused his father with his granduncle.[15][16][17][7][18] The Encyclopaedia Britannica (1911) mentions Drogheda as another possibility.[16] Voltaire in error believed Hamilton was born in Caen.[19]

- Anthony's father's article has more detail about these attempts to become a baronet.

- Anthony's father's article discusses his mistaken identity.

- Anthony's father's article gives a list of all the nine siblings.

- Anthony's father's article has some detail about Anthony's Protestant grandfather, the 1st Earl of Abercorn.

- Portrait in the National Portrait Gallery painted about 1700 and attributed to François de Troy.[75]

- Auger referred to St James in error as it would become the principal royal residence only in 1698.[87]

- The section "Comte d'Hamilton" in his brother George's article also discusses this noble title. Anthony is often called "Count" in French[134][19][135] as well as English sources,[136][6][137][131][138] but sometimes the title is omitted where one might expect it. Such is the case of his death certificate[139] and Berwick's letter in 1713 where he is called "M. Antony Hamilton".[140]

- OCiardha (2009) remarks that it is not sure that Hamilton went with the regiment to England.[178]

- In Hamilton's time there were two royal castles at Saint-Germain-en-Laye: The old (Château-vieux) and the new (Château-neuf).[204]

- This pension initially was 2,000 livres per year; in 1703 it was diminished to 1,320 but increased to 2,200 in 1717.[207] The 2000 livres were about £150 as the pound sterling was worth about 13 French livres (one Écu (60 sols or 3 livres) was worth 54 pence).[208][209] Per month this gave him about £12.5, equivalent to about £2,000 in 2021.[210]

- "Vue du Vieux Château de St. Germain en Laye", engraving by Jacques Rigaud (cropped), 1725.[213] The castle had stayed unchanged since the additions made for Louis XIV by Jules Hardouin-Mansart in the 1680s.[214]

- Hamilton was born in 1644 or 1645, while she was born after 1675 as this is when her older sister was born.[220]

- Zénéyde was written in 1695 as it mentions the death of François de Harlay, Archbishop of Paris, who died that year.[223][224][225]

- La Chesnaye (1774) and Dangeau (1857a) give Gramont's death in N.S., Chisholm (1910), in O.S.

- The Temple belonged to the Knights of Malta.[252] Philippe, Duke of Vendôme, was the grand prior of France 1878–1719 but was held prisoner in Switzerland, then exiled to Lyon until the death of Louis XIV in September 1715.[253] He also visited Malta in 1715 where he arrived on 7 April.[254] His friend Chaulieu lived at the Temple.[255]

- His death certificate states that he was buried on 21 April 1719 and had died the day before.[139] Dulon (1897) seems to be the first to give the right year.[256] Many give 1720 in error.[257][258][259][260][261]

- His father was entirely Scottish, his mother half Irish and haft English

- The suite, imagined by the Duc de Lévis, tells us how Zénéide meets Tigrane, prince of Armenia, travels to France to marry Childeric, is bewitched by Alboflède on an island in the Seine; how Alboflède kills Tigrane and almost Zénéide too, and how she is saved by the intervention of the river god and becomes a nymph of the Seine. Hamilton awakes all wet on river bank (read online).

Citations

- Cokayne 1910, p. 4. "Tabular pedigree of the Earls of Abercorn"

- Cokayne 1910, pp. 2–11

- Paul 1904, pp. 37–74

- Corp 2004a, p. 768, left column, line 39. "Anthony Hamilton died unmarried at the age of seventy-four at St Germain on 21 April 1719 (not 1720 as stated in many biographies) ..."

- Manning 2001, p. 149, line 6. "... there were two George Hamiltons, one being the nephew of the other. The older couple lived at Roscrea Castle and the younger couple, the parents of Anthony Hamilton were at Nenagh."

- Burke & Burke 1915, p. 54, right column, line 60. "3. Anthony, the celebrated Count Hamilton, author of the "Mémoires de Grammont", Lieut-Gen in the French service, died 20 April 1719, aged 74."

- Corp 2004a, p. 766, left column, line 45. "He was probably born at Roscrea, co. Tipperary, in 1644 or 1645."

- Auger 1805, p. 2, line 1. "Antoine Hamilton d'une ancienne et illustre maison d'Écosse, naquit en Irlande, vers l'année 1646."

- Chisholm 1910b, p. 884, first paragraph, top. "Hamilton, Anthony, or Antoine (1646–1720), French classical author, was born about 1646."

- Scott 1846, p. 4, line 4. "He [Anthony Hamilton] was, as well as his brothers and sisters, born in Ireland it is generally said, about the year 1646; but there is some reason to imagine that it was three or four years earlier."

- Merriam-Webster 1997, p. 799, right column. Transliterated from the book's own SAMPA, "\'nē-nä\"

- Ó Ciardha 2009a, 1st paragraph, 1st sentence. "Hamilton Anthony (Antoine) (1646?–1720) ... was probably born in Nenagh"

- Manning 2001, p. 149, line 4. "Gleeson adds that Anthony's father was also governor of Nenagh Castle for his brother-in-law and that Anthony might have been born there."

- Gleeson 1947, p. 102. Cited in Manning (2001) p. 149

- Brunet 1883, p. xiii, line 32. "Il parait aussi qu'il vit le jour à Roscrea, dans le comté de Tipperary, séjour ordinaire de son père, ..."

- Chisholm 1910b, p. 884, first paragraph, upper middle. "According to some authorities he was born at Drogheda, but according to the London edition of his works in 1811, his birthplace was Roscrea, Tipperary."

- Clark 1921, p. 4, line 24. "... Anthony Hamilton's biographers have assigned to Roscrea the honour of being his birth-place, as Anthony was supposed to have been born in 1646. He was, however, at this time at least a year old, but it is quite possible, of course, that he was born at Roscrea."

- Scott 1846, p. 4, line 7. "The place of his birth, according to the best family accounts, was Roscrea, in the county of Tipperary, the usual residence of his father ..."

- Voltaire 1922, p. 257. "Hamilton (Antoine, comte d'), né à Caën. On a de lui quelques jolies poésies, et il est le premier qui ait fait des romans dans un goût plaisant, qui n'est pas le burlesque de Scarron. Ses Mémoires du comte de Grammont, son beau-frère, sont de tous les livres celui où le fond le plus mince est paré du style le plus gai, le plus vif et le plus agréable."

- Corp 2004a, p. 766, left column, line 38. "Hamilton, Anthony [Antoine], Count Hamilton in the French nobility (1644/5?–1719), courtier and author, was the third of the six sons ..."

- Paul 1904, pp. 52. "Sir George Hamilton, fourth son of James, first Earl of Abercorn, who was seated at Donalong, in the county of Tyrone ..."

- Cokayne 1895, p. 149, line 27. "He [James Butler] was cr. [created] 30 Aug. 1642 Marquess of Ormonde [I. [Ireland]];"

- Barnard 2004, p. 156, left column. "Ormond was rewarded by being named by the king as lord lieutenant, and was sworn on 21 January 1644."

- Wasser 2004, p. 838, left column, line 43. "During the Irish wars he [George] served King Charles loyally, in association with his brother-in-law, James Butler, twelfth earl and first duke of Ormond."

- Mahaffy 1900, p. 53. "5 June [1634] Westminster. The King to the Lord Deputy for Claude Hamilton and Sir George Hamilton, Kt. and Bt. Ordering him to consider a petition ..."

- Cokayne 1903, p. 305, note c. "This non-assumption of the dignity [baronet] throws some little doubt on its creation."

- Carte 1851, p. 7. "... upon whose decease he [Thomas Butler] was by courtesy styled viscount Thurles."

- Burke & Burke 1915, p. 54, right column, line 35. "... Mary 3rd dau. [daughter] of Thomas Viscount Thurles and sister of the 1st Duke of Ormonde. He d. [died] 1679. She d. Aug 1680 ..."

- Cokayne 1889, p. 94. "1. Theobald Walter [ancestor of the Butlers] ... accompanied in 1185 John, Count of Mortaigue, Lord of Ireland ... into Ireland."

- Manning 2001, p. 150, last line. "... on May 1st 1640 by a grant ... to George Hamilton of Knockanderig ... of the manor, castle, town and lands of Nenagh for 31 years."

- Rigg 1890, p. 135 left column, line 55. "... was probably born at Roscrea, Tipperary, about 1646."

- Manning 2001, p. 150, line 42. "... February 28th 1635 regarding the marriage intended between Hamilton and Mary Butler, sister of the earl, which was to take place before the last day of April."

- Burke & Burke 1915, p. 54, right column, line 34. "[Sir George] m. (art. dated 2 June 1629) Mary, 3rd dau. of Thomas, Viscount Thurles ..."

- Cokayne 1903, p. 305, line 13. "He m. [married] in 1629 Mary, sister of James, 1st Duke of Ormonde [I. and E.], 3d. da. [daughter] of Thomas Butler, styled Viscount Thurles,"

- Paul 1904, p. 53, line 29. "He [George] married (contract dated 2 June 1629), Mary, third daughter of Thomas, Viscount Thurles ..."

- Corp 2004a, p. 766, right column, line 14. "Anthony Hamilton also had three sisters ..."

- Hayes 1943, p. 379. "He [Anthony] was reared in the Catholic religion, which was the religion of his parents, and he adhered to it till his death."

- Goodwin 1908, p. x, line 15. "Like his father, Anthony was a Roman Catholic."

- Wasser 2004, p. 838, left column, line 35. "His fourth son, Sir George Hamilton, first baronet (c. 1608–1679), soldier and landowner, was raised, along with his siblings, by his uncle, Sir George Hamilton of Greenlaw, who converted them to Roman Catholicism."

- Manning 2001, p. 151, line 23. "The younger Sir George fought with the earl of Ormond and is frequently mentioned in accounts of the wars."

- Clark 1921, p. 4. "Throughout this time of stress Sir George was a staunch ally to Ormonde and was employed by him on confidential missions."

- Airy 1886, p. 54, right column. "... and the cessation was signed on the 15 Sept. [1643]."

- Coffey 1914, p. 171. "A peace was signed on March 28th, 1646 without the Nuncio's knowledge."

- Coffey 1914, p. 180, line 16. "He [Rinuccini] therefore urged the clergy to reject the peace which had been concluded without his sanction."

- Manning 2001, p. 151, line 29. "The younger Lady Hamilton was brought to Dublin, presumably with her family, in 1646, with her mother, Lady Thurles, and her sisters: Lady Muskerry and the wife of the baron of Loghmoe as reported on May 30th 1646."

- Dunlop 1906, p. 530, line 28. " ... convoked a meeting of the clergy to Waterford, where on August 12 [1646] a resolution was passed condemning the peace and forbidding its proclamation under pain of excommunication ..."

- Carte 1851, p. 265. "... after taking Roscrea on Sept. 17 [1646], and putting man, woman, and child to the sword, except sir G. Hamilton's lady, sister to the marquis of Ormond ..."

- Sergeant 1913, p. 145, line 21. "For some reason, when the rebel leader Owen O'Neill took Roscrea, Tipperary, the home of the Hamiltons, in September 1646, and put the inhabitants to the sword, he spared Lady Hamilton and her young children—to which act of clemency we owe, incidentally, the Memoirs of Gramont, Anthony then but newly born."

- Manning 2001, p. 151, line 43. "This is more likely to have been the older Lady Hamilton considering that the younger Lady Hamilton was reported in May of that year as having been brought to Dublin."

- Carte 1851, pp. 299–300. "About the same time [Jan 1647], some persons of quality (particularly sir G. Hamilton the younger) arrived at Dublin, having been privately dispatched with signification of his majesty's pleasure, upon the advertisement he had received of the condition of Ireland to this purpose; 'that if it were possible for the marquis to keep Dublin ... but if there were or should be a necessity ... he should rather put them into the hands of the English than of the Irish.'"

- Airy 1886, p. 56, left column, line 29. "On the 28th [July 1647] Ormonde delivered up the regalia and sailed for England, landing at Bristol on 2 Aug."

- Clark 1921, p. 5, line 24. "In the spring of 1651 took place, at last, the event which had such a determining influence on the fate of the young Hamiltons. Sir George Hamilton left his country for France with his family ..."

- Coffey 1914, p. 207. "... Phelim McTuoll O'Neill stormed Nenagh ..."

- Gleeson 1936, p. 257. "It [Nenagh Castle] was taken by Phelim O'Neill in 1648 ... but was re-taken by Inchiquin ..."

- Carte 1851, p. 384, line 9. "He waited afterwards there [at Saint-Germain] until 11 August [1648]... he [Ormond] left sir G. Hamilton to receive what he was further to expect, and to send after him some things necessary to be provided, he set out for Havre de Grace, whither a Dutch man of war of forty-six guns, with a pass from the States, was sent by the prince of Orange to take him on board."

- Airy 1886, p. 56, left column, line 50. "... and in August, he himself began his journey thither. On leaving Havre, he was shipwrecked ... but at the end of September he again embarked, arriving at Cork on the 29th."

- Clark 1921, p. 5, line 2. "In January 1649, after the peace between the Lord Lieutenant and the Confederates, Sir George was appointed Receiver-General of the Revenues for Ireland, in the place of the Earl of Roscommon who had died."

- Cokayne 1903, p. 305 line 11. "... he was Col. [Colonel] of Foot and Gov. [Governor] of Nenagh castle"

- Warner 1768, p. 228. "... taking Nenagh and two other castles, on the tenth of November, he [Ireton] came to his winter quarters at Kilkenny."

- Cogan 1870, p. 67. "... against the continuance of His Majesty's authority in the person of the Marquess of Ormond, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland ..."

- O'Sullivan 1983, p. 284, line 15. "... boarding a small frigate, the Elizabeth of Jersey, at Galway on the 7th December, 1650 ..."

- Clark 1921, p. 5, line 19. "When Ormonde left the kingdom in December, 1650, Sir George would have accompanied him with his family, but the clergy having unjustly questioned his honesty as Receiver-General, he was obliged to stay and clear his name, which he did successfully."

- Millar 1890, p. 177, left column, line 46. "Marquis of Ormonde, whom he followed to Caen in the spring of 1651 with his wife and family."

- Clark 1921, p. 7, line 3. "Caen was doubtless the place where Sir George settled his family at first ..."

- Brunet 1883, p. xiv, line 8. "... Hamilton, au printemps de 1651, conduisit sa femme et toute sa famille en France, et il résida près de Caen avec lord et lady Ormond."

- Clark 1921, p. 8, line 14. "... James the eldest also joined the wandering court, though the precise nature of his connexion is not known."

- Clark 1921, p. 8, line 13. "... George, the second son, was made a page to Charles II ..."

- Perceval-Maxwell 2004, pp. 130–131. "... in August 1652 she [Lady Ormond] left for England with her family ..."

- Clark 1921, p. 8, line 27. "... his [Anthony Hamilton's] mother and his aunt, Lady Muskerry, had apartments at the couvent des Feuillantines in Paris ..."

- Saint-Simon 1899, p. 560, line 8. "Il [Gramont] arriva à Londres le 15 janvier 1663, et retrouva entre autres camarades, les Hamilton, de grande maison écossaise et catholique, dont il avait fréquenté plusieurs jeunes gens au Louvre dans l'entourage de la veuve et du fils de Charles 1er."

- Fryde et al. 1986, p. 44, line 39. "Charles II. ... acc. 29 May 1660 ..."

- Wauchope 2004b, p. 888, right column, line 11. "... until the restoration when the family moved to Whitehall."

- Elliott 2000, p. 114. "The Scottish settlers Sir George Hamilton and his brother Claud, Lord Strabane, were restored in Tyrone ..."

- Chisholm 1910b, p. 884, first paragraph, lines lower middle. "The fact that, like his father, he [Anthony Hamilton] was a Roman Catholic prevented his receiving the political promotion ..."

- Corp 2004c, p. 185. "A portrait of Anthony Hamilton can be dated to about 1700 ..."

- Rigg 1890, p. 135, right column, line 17. "These two brothers are frequently mentioned in the Mémoires."

- Burke & Burke 1915, p. 54, right column, line 38. "1. James, col. in the service of Charles II and Groom of the Bedchamber, m. [married] 1661, Elizabeth, dau. [daughter] of John, Lord Colepeper."

- Clark 1921, p. 16. "James Hamilton's marriage to Elizabeth, daughter of Sir John Colepeper ... took place as early as 1660 or 1661. As the lady was a Protestant, James Hamilton left the Church of Rome shortly before his marriage, to the great sorrow and anger of his devout mother ..."

- Clark 1921, p. 14, line 17. "... Charles ... obtained the hand of one of the Princess Royal's maids of honour for him."

- Clark 1921, p. 12, line 1. "It was in the beginning of 1661 that Sir George Hamilton brought his wife and younger children to England. His elder sons had already preceded him."

- Clark 1921, p. 12, line 22. "The family, the six sons and three daughters, lived for some time in a large comfortable house near Whitehall ..."

- Auger 1805, p. 2, line 28. "Près de deux ans après le rétablissement de Charles II, arriva à Londres le fameux chevalier de Grammont, exilé de France ..."

- Hamilton 1713, p. 104. "La Motte Houdancourt étoit une des filles de la Reine-Mère."

- Auger 1805, pp. 2–3. "Près de deux ans après le rétablissement de Charles II, arriva à Londres le fameux chevalier de Grammont, exilé de France pour avoir voulu disputer à son maître le cœur de mademoiselle La Mothe-Houdancourt."

- Fraser 2007, p. 115, line 3. "Charlotte-Eléanore La Motte Houdancourt, another maid of honour ..."

- Auger 1805, p. 2, line 26. "... on parloit françois a St.-James presqu'aussi habituellement qu'à Versailles."

- Weinreb & Hibbert 2008, p. 716, left column, line 7. "After the destruction by filre of Whitehall Palace in 1698, St James became the principal royal residence ..."

- Corp 2004b, p. 286, left column. "Elizabeth's brother Anthony became his [Gramont's] close friend ..."

- Lewis 1958, p. 169, line 5. "... [Philibert] was at once welcomed into the king's raffish entourage of mistresses and roués ..."

- Lewis 1958, p. 171, line 13. "... Then he [Philibert] met Miss Hamilton and in a trice Middleton and Warmestre were forgotten ..."

- Jusserand 1892, p. 94, line 13. "With this view [of marriage] he [Gramont] has cast his eyes on a beautiful young demoiselle of the house of Hamilton ..."

- Wheatley 1912, p. 263, note 15. "This well known story is told in a letter from Lord Melfort to Richard Hamilton ..."

- Auger 1805, p. 3. "Chevalier de Grammont, lui crièrent-ils [Anthony and George] du plus loin qu'ils l'aperçurent chevalier de Grammont avez-vous rien oublié à Londres? — Pardonnez-moi, Messieurs, j'ai oublié d'épouser votre sœur."

- Michel 1862, p. 368, line 9. "... Antoine et George ... lui dirent en l'abordant 'Chevalier de Grammont, n'avez-vous rien oublié à Londres?'—'Pardonnez-moi, messieurs, j'ai oublié d'épouser votre sœur.'"

- La Chesnaye des Bois 1866a, p. 642, line 28. "Susanne-Charlotte mariée à Henri Mitte, Marquis de Saint-Chamond ..."

- Clark 1921, p. 22, line 19. "... it might seem as if the two 'troublesome brothers', alarmed by the chevalier's sudden departure for France, had delayed his expedition and exacted a public engagement."

- Lewis 1958, p. 173, line 28. "Later in the year Philibert heard from his sister, Madame de St-Chaumont ... that Louis XIV had given him leave to return ..."

- Lewis 1958, p. 174, line . "... a visit from his brother the Maréchal, with orders for him to return to England at once."

- Clark 1921, p. 23–24. "... marriage only took place in the end of December and amidst circumstances which would completely justify one in placing the anecdote there."

- Hartmann 1930a, p. 378. "The chevalier de Gramont's rare constancy had met with its reward long before, towards the end of December 1663."

- Paul 1904, p. 55, pemultimate line. "... she [Elizabeth] married in 1664 the dissipated Philibert, Count de Gramont ..."

- Saint-Simon 1899, p. 563, line 8. "Le contrat de mariage fut passé sans autre retard, le 9 décembre 1663 (style anglais) ..."

- Louis XIV 1806, p. 170. "Au comte de Grammont. Paris le 6 mars 1664. Monsieur Le Comte de Grammont. Il ne faut point que l'impatience de vous rendre auprès de moi, trouble vos nouvelles douceurs. Vous serez toujours le bien-venu ..."

- Corp 2004a, p. 766, right colum, last line. "... when he was cashiered for refusing to take the oath of supremacy;"

- Clark 1921, p. 32, bottom. "It is more than likely that Anthony accompanied him to France at this time, since we know that the two brothers served there together."

- Silke 1976, p. 609. "... in 1671 Sir George Hamilton recruited an infantry regiment of 1,500 for France."

- Goodwin 1908, p. x, line 23. "He [Anthony] was again in Ireland in 1671, apparently to assist his brother, who had obtained permission from the King to levy secretly a regiment of 1500 men in that country for the French service. A news-letter of the day (printed in the State Papers) records a gallant deed performed by him on the night of May 19, when a destructive fire broke out in the storehouse of Dublin Castle."

- Ó Ciardha 2009a, 2nd paragraph, 2nd sentence. "... he [Anthony] saved Dublin castle from total destruction during a fire by carrying out a barrel of gunpowder."

- Corp 2004a, p. 766, right column, line 21. "They [Anthony and Richard] served in the Franco-Dutch war 1672-8."

- Wauchope 2004b, p. 888, right column, line 12. "... George raised a regiment for service in France in 1671 in which both Richard and another brother Anthony ... took commissions."

- Clark 1921, p. 45, line 26. "... left in garrison in Liége."

- Clark 1921, p. 46. "... proceeded to Utrecht, which fell on the 20th of June [1672]."

- Rigg 1890, p. 135 right column, line 33. "... in Limerick in 1673 holding a captain's commission in the French army and recruiting for his brother's [George's] corps."

- Hamilton 1811, frontispiece

- Sergeant 1913, p. 213. "In 1674 he [George Hamilton] was engaged in two desperate struggles between Turenne and the Duke of Bournonville, at Sintzheim on June 16th and at Entzheim on October 6th, on both occasions playing a distinguished part in Turenne's victory."

- Clark 1921, p. 54. "George and Anthony were both wounded."

- Clark 1921, p. 56, line 10. "He [George Hamilton] left in the very beginning of March [1675], but Anthony was put in charge of the difficult expedition, and with him was his younger brother Richard, who must have entered the French service some time before."

- Clark 1921, p. 56, bottom. "All in a sudden, in the first week of April [1675], the French ships arrived unexpectedly in Kinsale."

- Clark 1921, p. 56, line 31. "Hamilton expected the French ships on the 8th of March [1675] but they did not appear."

- Clark 1921, p. 55, line 31. "Turenne defeated them at Mulhouse on the 29th of December and at Turckheim on January 5th. George and Anthony did not, however, take part in these operations ..."

- Clark 1921, p. 213, last line. "Hamilton was at his side when the fatal shot struck him down ..."

- Atkinson 1946, p. 166, line 15. "... of Hamilton's 450 [killed and wounded]."

- Atkinson 1946, p. 166, line 39. "... Condé, who had been securing a strong position on the Meuse, was hurried to Alsace with reinforcements, and was able to hold the Imperialists in check ..."

- Longueville 1907, p. 392. "The King made Condé leave his army in Flanders to take the command vacated by the death of Turenne."

- Lynn 1999, p. 142. "... at the end of this campaign, Condé left the army to spend his final decade on his estate ar Chantilly."

- Clark 1921, p. 62. "He [George] had to raise 1100 men, and while Anthony or possiblt Ricgard remained in Tool with the regiment he proceeded to England ... "

- Historical Manuscripts Commission 1906, p. 6. "1675-6, January 22 ... arrivall of Comte Hamilton ... Ye Monsieurs are now come ..."

- Jullien de Courcelles 1823, p. 54. "Nommé commandant de l'armée d'Allemagne, par pouvoir du 10 mars 1676 ..."

- Clark 1921, p. 63. "Near Saverne Lorraine [i.e. the duc de L.] attacked his [Luxembourg's] rear-guard, commanded by George Hamilton, but was driven back in a fierce combat, in which Hamilton and his regiment fought with all possible bravery ... George Hamilton fell. This was on the 1st of June, 1676."

- Sergeant 1913, p. 217. "At the beginning of June [1676] he took part in the battle of Zebernstieg [Col de Saverne] and was engaged in covering the French retreat on Saverne when he was killed by a musket-shot."

- Corp 2004c, p. 217, line 1. "Anthony Hamilton had inherited his brother's title in 1678."

- Clark 1921, p. 32, note 6. "As for Anthony, who is so often styled 'Çount' Anthony, there is no evidence whatsoever to show that he bore this title during his lifetime."

- Rigg 1890, p. 136, left column, line 10. "It is not clear when and how he [Anthony] obtained his title of count.."

- Parfaict 1756, pp. 535–538. "Triomphe de l'Amour, ballet en vingt entrées de M. Quinault ... [p. 538] Zéphyrs. M. le Prince de la Roche-sur-Yon, M. de Vermandois, Messieurs les marquis d'Alincourt, de Moy et de Richelieu, M. le Comte d'Hamilton."

- La Chesnaye des Bois 1774, p. 630. "Elle [the countess de Gramont] avoit pour frère Antoine, Comte d'Hamilton ..."

- Webb 1878, p. 241, left column, line 12. "Hamilton, Count Anthony was born ..."

- Corp 2004a, p. 766, right column, line 22. "In 1678, having inherited the title of count from his brother, Anthony left France."

- Paul 1904, p. 55, line 1. "... she [Elizabeth Hamilton] died, 3 June 1708, aged sixty-seven."

- Kissenberth 1907, p. 43. "Im folio 31 der 'régistres paroissiaux, année 1719' fand ich unter dem 22. April den Totenschein Hamiltons den ich hier getreu nach dem Original wiedergebe: 'Acte de décès. Le même jour a été inhumé dans cette église le corps de mre. [messire] Antoine Hamilton marechal de camp de la maison d'Abercorne en Ecosse décédé sur cette paroisse le jour précédent âgé de soixante et quatorze ans ...'."

- Historical Manuscripts Commission 1902, p. 267. "I wonder M. Antony Hamilton will still be rambling ..."

- Wauchope 2004a, p. 523, right column, line 10. "... [Thomas Dongan] in 1671 was appointed lieutenant-colonel of George Hamilton's Irish regiment in French pay."

- Atkinson 1946, pp. 168–169. "'Anthony Hamilton' Sarsfield wrote on 1st July [1676] 'quits'; he was told by Louis that he could not afford to give him a regiment this year."

- Clark 1921, p. 65. "It is somewhat uncertain whether Anthony Hamilton continued to serve in the regiment ..."

- Atkinson 1946, p. 168 bottom. "... the Lieutenant-Colonelcy going to Richard Hamilton ..."

- Lynn 1999, p. 156, line 33. "... the French and Dutch signed the Treaty of Nijwegen on 10 August [1678]."

- Clark 1921, p. 69, bottom. "In December [1678] Louis ... disbanded the regiment d'Hamilton ..."

- Dulck 1989, p. 7. "Suit une période assez obscure. Il [Anthony] vit en Irlande de 1677 à 1684, puis rentre à Londres ..."

- Cokayne 1903, p. 305 line 17. "James Hamilton, of Donalong aforesaid, grandson and h.[heir] being 1st s. [son] and h. of Col. James Hamilton, Groom of the Bedchamber "

- Clark 1921, p. 71, line 19. "In the summer of 1681 he was definitely established at Dublin ..."

- Auger 1805, p. 5, line 13. "Quelques années auparavant, en 1681, dans un de ces voyages qu'il faisoit en France, il avoit vu ce même St-Germain l'asile des plaisirs et de la volupté, et il avoit été choisi par le roi pour figurer dans le Triomphe de l'amour, ballet de Quinault."

- Rigg 1890, p. 135 right column, middle. "He [Anthony Hamilton] appeared as a zephyr in the performance of Quinault's ballet, the 'Triomphe d'amour,' at St. Germain-en-Laye in 1681."

- Corp 2004a, p. 766, right column, line 26. "During this period he appeared alongside the dauphin as a zephyr in Lully's ballet Le triomphe de l'amour, which was given twenty-nine performances in the Château de St Germain-en-Laye in January and February 1681."

- Wauchope 2004b, p. 888, right column, line 20. "... he [Richard Hamilton] danced before Louis XIV as a zephyr in Quinault's ballet Le triomphe de l'amour at St Germain-en-Laye"

- Clark 1921, p. 72, line 1. "It would thus seem that the above Count Hamilton was Richard ..."

- Fryde et al. 1986, p. 44, line 46. "James II. ... acc. 6 Feb. 1685 ..."

- McGuire 2009, p. 12th paragraph. "In late April Talbot was sent to Ireland to purge the entirely protestant Irish army of ‘disaffected officers’ or, as Talbot called them, ‘Cromwellians’."

- Walsh & Doyle 2009, 2nd paragraph. "Tyrconnell had already overseen a significant ‘catholicisation’ of the army in Ireland during 1685."

- Wauchope 2004b, p. 888, right column, line 31. "He [Richard] was made a colonel of dragoons on the Irish establishment by James II on 20 June 1685, and in April 1686 he was promoted to brigadier, making him (after Tyrconnell and Justin MacCarthy) the third most senior member of the Irish army."

- Clark 1921, p. 74, line 12. "John, the youngest brother, was lieutenant in Lord Mount joy's regiment."

- Clark 1921, p. 74, line 10. "Anthony also took service in Ireland as Sir Thomas Newcomen's Lieutenant-Colonel in his regiment of foot."

- Cokayne 1896, p. 445. "... cr. [created] him 20 June 1685 Baron of Talbotstown, co. Wicklow, Viscount Baltinglass, also in co. Wicklow, and Earl of Tyrconnell ..."

- Clark 1921, p. 75, line 8. "... he [Antoine Hamilton] was, however, appointed Governor of Limerick in 1685, in place of the Protestant Governor, Sir William King, who was deposed, and his company quartered in Limerick."

- Gibney 2009, 2nd paragraph. "As governor of Limerick during the anti-catholic scares caused by the 'popish plot' of 1678, King took an active and assiduous role in improving fortifications and pursuing suspects, often in association with Orrery."

- Clark 1921, p. 75, line 11. "The new Governor went publicly to mass, an event unheard of since 1650."

- Lenihan 1866, p. 210. "On the 1st of August, same year [1685], Lieut.-Colonel Anthony Hamilton came to Limerick as Governor, in place of Sir William King, who was deposed. Hamilton was the first Governor who for 35 years before publicly went to Mass."

- Clark 1921, p. 76, line 9. "Clarendon ... speaks very kindly of Anthony Hamilton, and describes him as a man who understands the regiment better than the Colonel, ' for he makes it his business/"

- Clark 1921, p. 76, line 25. "Men, he said, were put out of that regiment who were as good men as were in the world, and he did not think so of those who replaced them."

- Ó Ciardha 2009a, 2nd paragraph, 6th sentence. "In the same year [1685] ... was appointed to James II's privy council."

- Corp 2004a, p. 767, left column, line 2. "At the end of the following year [i.e. 1686] he was sworn of the irish privy council ..."

- Corp 2004a, p. 767, left column, line 2. "... and promoted to the rank of colonel in February 1687."

- Bickley 1972, p. 291. "... Stephen Taaff to be ensign of Major Barnwall's company in Col. Anthony Hamilton's Regiment of foot;"

- Shepherd 1990, p. 26, line 1. "On Tuesday 25 September 1688 ... Tyrconnell received an urgent demand from London to sent four regiments of Irish troops to England."

- Childs 2007, p. 3. "To strengthen his forces in the face of the Dutch threat, James ordered the better elements of the Irish army into England. One regiment of dragoons, a battalion of the Irish Foot Guards, and Anthony Hamilton's and Lord Forbes's battalions of line infantry ..."

- Dalton 1896, p. 221. "Irish Regts. which came to England at the revolution in 1688 ... Col. Butler's Dragoons ... King's Foot Guards ... Lord Forbes Regt of Foot ... Col. Hamilton's Regt. of Ft. / Ant. Hamilton ... Col. McElligott's do. [do.=ditto; i.e. another regiment of foot] ..."

- Shepherd 1990, p. 26, line 14. "The Irish reinforcements began arriving at Chester, Liverpool and neighbouring ports in early October 1688. The Irish ... and Anthony Hamilton marched through the midlands, arriving at their quarters in and around London by the end of the month."

- Handley 2004, p. 881, right column, line8. "... James II made him [Berwick] Governor of Portsmouth on 1 December 1687 ..."

- Jones 1982, p. 148. "... Portsmouth, where they remained with ... Colonel Anthony Hamilton's regiments of foot and two regiments of English soldiers, until the surrender of that place on the 20th [December 1688]."

- Ó Ciardha 2009a, 3rd paragraph, 2nd sentence. "It is not known whether Hamilton accompanied these forces."

- Gardiner 1895, p. 1689. "On December 23, with William's connivance, James embarked for France."

- King 1730, p. 88 ps=. "A List of all the Men of Note that came with King James out of France .../ Col. Anthony Hamilton. / Col. John Hamilton."

- O'Callaghan 1854, p. 15, line 7. "On the revolt of England against the King in 1688, he [Anthony] retired, as his Sovereign did, to France, and was one of those officers who accompanied him from Brest to Ireland."

- Doherty 1998, p. 29, line 1. "... James II landed at Kinsale from France on 12 March 1689."

- Ó Ciardha 2009b, 2nd paragraph, 4th sentence. "... Hamilton tricked William, broke his parole, and once having reached Ireland remained there and joined the Jacobites."

- Clark 1921, p. 93. "Anthony Hamilton had been appointed Major-General in the early part of the summer [1689]."

- Hogan 1934, p. 257,33 line . "... le duc de Barwick est posté entre Dery et Iniskilin, Antoine Amilton à Belterbot, et un nommé Sasphilt [Sarsfield] du costé de Sligo."

- Boulger 1911, p. 109. "The cavalry of his force was commanded hy Anthony Hamilton, and the result showed that he was better with his pen than his sword."

- Hogan 1934, pp. 384-385. "... il [Montcachel] dit à Antoine Hamilton d'aller avec treize compagnies de dragons chasser un parti qui paroissoit, et occuper ensuitte un passage où cent hommes pourraient en arrester dix milles."

- Shepherd 1990, p. 66. "... the Enniskilleners recovered, and ambushed and massacred Hamilton's dragoons."

- Rigg 1890, p. 135, right column, bottom. "With the rank of major-general he [Anthony] commanded the dragoons, under Lord Mountcashell, at the siege of Enniskillen, and in the battle of Newtown Butler on 31 July 1689 was wounded in the leg at the beginning of the action, and his raw levies were routed with great slaughter."

- Simms 1969, p. 117. "... Hamilton continued his flight till he reached Navan in County Meath."

- D'Alton 1861, p. 431. "Regiments of dragoons. Colonel Francis Carrol's ... Captains ... Peter Lavallen"

- Clark 1921, p. 96. "Rosen presided over the court ... Anthony was acquitted and Lavallin, who to the end protested that he had repeated the order as it had been given to him, was put to death."

- O'Callaghan 1854, p. 15, line 37. "It was in the spring of 1690 ... that the formation of the force, styled 'Irish Brigade in the Service of France' was commenced ...'"

- Hogan 1934, p. 287. "... Sa Maiesté ne veut point pour commandant des troupes Irlandoises qui viendront à son service, pas mesme pour un des colonels, des Srs. d'Hamilton qui ont servy en France ..."

- Boulger 1911, p. 158. "With regard to Anthony Hamilton, whose name has just been mentioned, it may be stated that he did participate in the cavalry charges."

- Ó Ciardha 2009a, 3rd paragraph, last sentence. "He later fought in the second line of cavalry at the Boyne and Limerick."

- Simms 1976, p. 501. "... he [William] decided to raise the siege and return to the England at the end of August."

- Boulger 1911, p. 199. "[Sept 1688]... he [Tyrconnell] sent Anthony Hamilton to France with news of the raising of the siege ..."

- Rigg 1890, p. 136, left column, line 8. "He does not appear to have been present at the battle of Aughrim."

- Burke 1869, p. 3, left column, line 27. "John, Colonel in the army of James II., killed at the battle of Aughrim."

- Boulger 1911, p. 244. "Major-General John Hamilton, who died at Dublin soon after his wounds."

- Ó Ciardha 2009a, Last paragraph, 1st sentence. "Hamilton spent the remainder of his life at Saint-Germain, where he died on 21 April 1720 ..."

- Corp 2004c, p. 76, line 6. "[Louis XIV] decided that the Château-vieux de Saint-Germain-en-Laye would be more suitable."

- Corp 2004c, p. 76, line 22. "James II was given the larger of the two royal châteaux, known as the château-vieux. The other one, the château-neuf ..."

- Corp 2004c, p. 216, line 21. "He [Anthony] never had a post in the royal household ..."

- Corp 2004a, p. 767, left column, line 29. "Hamilton was given a generous pension by James II ..."

- Corp 2004c, p. 216, note 4. "Hamilton was given a pension of 2000 livres per annum, later reduced to 1320 livres in 1703 but increased to 2200 livres by 1717."

- Stanley, Newton & Ellis 1702, 1st table. "The Ecu of France of 60 sols Turnois / 54.13 pence"

- Hogan 1934, p. 300. "L'Ecu de France ... 5[s] 0[d]"

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Corp 2004a, p. 768, left column, line 30. "He [Anthony] continued to live in the Château de Saint-Germain where he had an apartment and where he was looked after in his last years by Mrs. Lockhart, the widow of a fellow Jacobite."

- Haile 1905, p. 276, line 6. "... the most brilliant ornament of that exiled court was Anthony Hamilton ..."

- Corp 2004c, p. 80. Figure 4

- Corp 2004c, p. 83. "... during the 1680s LouisXIV had ordered Hardouin-Mansart to add a pavillion to each of the five corners of the château."

- Corp 2004c, p. 217, line 4 . "At the exiled court Hamilton was on particularly good terms with the Duke of Berwick's second wife Anne (née Bulkeley) and her three sisters Charlotte (Viscountess Clare), Henrietta and Laura (both unmarried) ..."

- Humphreys & Wynne 2004, pp. 579–580. "... she married ... Henry Bulkeley (c.1641–1698) fifth but third surviving son of Thomas, 1st Viscount Bulkeley ... he was master of the household to Charles II and James II ..."

- Brunet 1883, p. xvi, line 3. "Il [Hamilton] voyait surtout le duc de Berwick (fils de Jacques II); la duchesse était la nièce de la belle Stewart, qui occupe tant de place dans les Mémoires."

- Haile 1905, p. 277, line 10. "... her daughter Anne, Hamilton's “belle Nanette,” was to marry the Duke of Berwick as his second wife."

- Dulon 1897, p. 58. "Le duc de Berwick se remaria à Mlle Anne de Bulkeley, seconde fille de Henri de Bulkeley et de Sophie Stuart, première dame d'honneur de la reine d'Angleterre, Marie d'Este [Mary of Modena]. Ce dernier mariage fut célébré à Saint-Germain-en-Laye, le 20 avril 1700 ..."

- Handley 2004, p. 882, right column. "In Paris on 18 April 1700 he [Berwick] married Anne (c. 1675–1751), daughter of Henry Bulkeley, master of the household to James II."

- Scott 1846, p. 9, line 5. "... he was a particular admirer of Henrietta Bulkeley; but their union would have been that of hunger and thirst, for both were very poor ..."

- Brunet 1883, p. xvi, line 10. "Il paraît avoir été épris d'Henriette, mais elle n'avait point de fortune; lui-même était dans une position fort embarrassée ... Un mariage était donc impossible, parce qu'il y avait un rang à soutenir;"

- Clark 1921, p. 126, note. "The tale of Zeneyde ... can be dated through the reference to the death of the Archbishop of Paris, Harlay."

- Hamilton 1849, p. 280. "... the late Archhishop of Paris, who occupied one-half of the terrace with his chariot and eight horses ..."

- La Chesnaye des Bois 1866b, p. 342, right column. "... un Archevêque de Paris dans François de Harlay, l'un des Grands Prélats de son siècle, mort le 6 Août 1695, âgé de 70 ans."

- Corp 2004c, p. 238. "... Hamilton put it: 'there is no mercy here for those who do not spend half their day at their prayers or at any rate make a show of doing so'.

- Corp 2004c, p. 217, line 7. "In 1701 he [Hamilton] accompanied Berwick on his misson to Rome to obtain the support of the new Pope Clement XI for the Jacobite cause."

- Corp 2004c, p. 57, line 9. "... on 4 March [1701] ... James II suffered a major stroke."

- Corp 2004c, p. 60, note 266. "Berwick left Saint-Germain for Rome on 17 January 1701 and returned there on 2 April."

- Burke & Burke 1915, p. 38. "James II (who d. [died] 16 Sept. 1701, at St. Germains, where he was buried.) ..."

- Dulon 1897, p. 29. "Maladie et décès de Jacques II au Château-vieux de Saint-Germain-en-Laye."

- Corp 2004c, p. 227. "... his poem: 'Sur l'Agonie du feu Roi d'Angleterre'."

- Corp 2004c, p. 217, line 12. "In May 1703 Louis XIV gave Hamilton's sister the use during her lifetime of a house near Meudon called 'Les Moulineaux'. In the five years until her death in June 1708 it was much frequented and became the centre of [Anthony] Hamilton's social world."

- Clark 1921, p. 122. "When Félix, the chief-surgeon, died in 1703, a small property of his, les Moulineaux, which lay within the grounds of Versailles, fell vacant and the king at once gave it to Madame de Gramont, a present which caused no little talk ..."

- Corp 2004c, p. 217, line 33. "Hamilton's decision to write the 'Mémoires de la vie du comte de Grammont' his brother in law, was originally taken in 1704, while the two men were at Séméac in Gascogne ..."

- Corp 2004c, p. 217, line 9. "At the French court Hamilton frequented the circle of the duc and duchesse du Maine, particularly after 1700 when the latter first occupied the Château de Sceaux."

- Clark 1921, p. 137, line. "Hamilton was described at Sceaux as the Horace of Albion ..."

- Chisholm 1910b, p. 884, first paragraph, penultimate sentence. "With Ludovise, duchesse du Maine, he became an especial favourite, and it was at her seat at Sceaux that he wrote the Mémoires that made him famous."

- Jullien 1885, p. 51, line 17. "Hamilton a laissé un récit bien spirituel de cette nuit du 9 au 10 août 1705 à laquelle il eut l'honneur d'assister."

- La Chesnaye des Bois 1866a, p. 642, line 10. "Il mourut le 30 janvier 1707, âgé de 86 ans "

- Chisholm 1910a, p. b333, first paragraph, bottom. "[Gramont] died on the 10th of January 1707, and the Mémoires appeared six years later."

- Dangeau 1857a, p. 293. "Dimanche 30 [Janvier 1707] ... Le comte de Gramont mourut à Paris la nuit passée."

- Saint-Simon 1929, p. 415, line 6. "Il [James III] ne devoit être suivi, comme en effet il ne le fut, que [among others] ... des deux Hamiltons [Anthony & Richard] ..."

- Saint-Simon 1929, p. 427, note 7. "Jái dit qu'il n'y en avait qu'un."

- Luttrell 1857, p. 282. "Besides the French general officers on board, he [James III] had with him 4 of his own country, viz. Dorington, Richard Hamilton, Skelton and Galmoy;"

- Dangeau 1857b, p. 150. "June 1708. Dimanche 3 ... La comtesse de Gramont mourut à Paris."

- Paul 1904, p. 56, line 7. "... she [Elizabeth Hamilton] died, 3 June 1708, aged sixty-seven."

- Miller 1971, p. 147, line 8. "On 11 April 1713 the peace was signed at Utrecht: in return for the acknowledgement of his grandson as Philip V of Spain, Louis had had to recognize the Hanoverian and Protestant succession in England."

- Corp 2004a, p. 768, left column, line 18. "... his brother Richard had followed James III and most of his courtiers to Bar-le-Duc in Lorraine."

- Corp 2004c, p. 9. "Queen Mary of Modena, however, was allowed to remain at Saint-Germain after the departure of her son and continued to maintain there a large royal household."

- Rousseau 1968, p. 185, line 13. "... Voltaire a connu Hamilton dans la société du Temple peu avant 1715;"

- Piganiol de La Force 1765, p. 340. "Les Chevaliers de S. Jean de Jerusalem entrèrent donc en possession du Temple."

- Saint-Simon 1910, p. 168, line 9. "... permission du Roi [for the grand prior] de venir démeurer à Lyon, mais sans approcher la cour ni Paris ..."

- Anselme 1726, p. 199. "... il [Philippe] passa en 1715 à Malthe au secours de fa religion, menacée par les Turcs; y arriva le 7. avril;"

- Raunié 1884, p. xiii. "... l'abbé de Chaulieu qui mangeait gaiement ses revenus ecclésiastiques dans sa petite maison de l'enclos du Temple, rendez-vous d'une société aussi spirituelle que désordonnée."

- Dulon 1897, p. 104. "... il [Hamilton] y [at Saint-Germain] mourut, après l'avoir habitée pendant 31 ans, le 21 avril 1719."

- Auger 1805, p. 7, line 12. "Hamilton mourut a St.-Germain-en-Laye, le 6 août 1720, âgé d'environ soixante-quatorze ans."

- Chisholm 1910b, p. 884, first paragraph, last sentence. "He died at St. Germain-en-Laye on the 21st of April 1720."

- Webb 1878, p. 241, left column. "He died at St. Germain's, in 1720, aged 74."

- Scott 1846, p. 15. "Hamilton died at St. Germain, in April, 1720, aged about 74."

- Rigg 1890, p. 136, left column, line 27. "He [Anthony Hamilton] died at St. Germain-en-Laye on 21 April 1720."