Antiochus X Eusebes

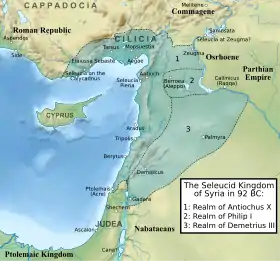

Antiochus X Eusebes Philopator (Ancient Greek: Ἀντίοχος Εὐσεβής Φιλοπάτωρ; c. 113 BC – 92 or 88 BC) was a Seleucid monarch who reigned as King of Syria during the Hellenistic period between 95 BC and 92 BC or 89/88 BC (224 SE [Seleucid year]).[note 1] He was the son of Antiochus IX and perhaps his Egyptian wife Cleopatra IV. Eusebes lived during a period of general disintegration in Seleucid Syria, characterized by civil wars, foreign interference by Ptolemaic Egypt and incursions by the Parthians. Antiochus IX was killed in 95 BC at the hands of Seleucus VI, the son of his half-brother and rival Antiochus VIII. Antiochus X then went to the city of Aradus where he declared himself king. He avenged his father by defeating Seleucus VI, who was eventually killed.

| Antiochus X Eusebes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Antiochus X's portrait on the obverse of a tetradrachm | |||||

| King of Syria | |||||

| Reign | 95–92 or 88 BC | ||||

| Predecessor | Seleucus VI, Demetrius III | ||||

| Successor | Demetrius III, Philip I | ||||

| Born | c. 113 BC | ||||

| Died | 92 or 88 BC (aged 21–22 or 24–25) | ||||

| Spouse | Cleopatra Selene | ||||

| Issue | Antiochus XIII Seleucus VII Philometor Seleucus Kybiosaktes | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Seleucid | ||||

| Father | Antiochus IX | ||||

| Mother | Cleopatra IV ? | ||||

Antiochus X did not enjoy a stable reign as he had to face three of Seleucus VI's brothers, Antiochus XI, Philip I and Demetrius III. Antiochus XI defeated Antiochus X and expelled him from the capital Antioch in 93 BC. A few months later, Antiochus X regained his position and killed Antiochus XI. This led to both Philip I and Demetrius III becoming involved. The civil war continued but its final outcome is uncertain due to the contradictions between different ancient historians' accounts. Antiochus X married his stepmother, Antiochus IX's widow Cleopatra Selene, and had several children with her, including a future king Antiochus XIII.

The death of Antiochus X is a mystery. The year of his demise is traditionally given by modern scholars as 92 BC, but other dates are also possible including the year 224 SE (89/88 BC). The most reliable account of his end is that of the first century historian Josephus, who wrote that Antiochus X marched east to fight off the Parthians who were attacking a queen called Laodice; the identity of this queen and who her people were continues to be debated. Other accounts exist: the ancient Greek historian Appian has Antiochus X defeated by the Armenian king Tigranes II and losing his kingdom; the third century historian Eusebius wrote that Antiochus X was defeated by his cousins and escaped to the Parthians before asking the Romans to help him regain the throne. Modern scholars prefer the account of Josephus and question practically every aspect of the versions presented by other ancient historians. Numismatic evidence shows that Antiochus X was succeeded in Antioch by Demetrius III, who controlled the capital in c. 225 SE (88/87 BC).

Background, early life and name

The second century BC witnessed the disintegration of the Syria-based Seleucid Empire due to never-ending dynastic feuds and foreign Egyptian and Roman interference.[2][3] Amid constant civil wars, Syria fell to pieces.[4] Seleucid pretenders fought for the throne, tearing the country apart.[5] In 113 BC, Antiochus IX declared himself king in opposition to his half-brother Antiochus VIII.[6] The siblings fought relentlessly for a decade and a half until Antiochus VIII was killed in 96 BC.[7] The following year, Antiochus VIII's son Seleucus VI marched against Antiochus IX and killed him near the Syrian capital Antioch.[8]

Egypt and Syria attempted dynastic marriages to maintain a degree of peace.[9] Antiochus IX married several times; known wives are his cousin Cleopatra IV of Egypt, whom he married in 114 BC,[10][11] and her sister Cleopatra Selene, the widow of Antiochus VIII.[note 2][15] Some historians, such as John D. Grainger, maintain the existence of a first wife unknown by name who was the mother of Antiochus X.[7] Others, such as Auguste Bouché-Leclercq, believe that the first wife of Antiochus IX and the mother of his son was Cleopatra IV,[10] in which case Antiochus X would have been born in c. 113 BC.[16] None of those assertions are based on evidence, and the mother of Antiochus X is not named in ancient sources.[17] Antiochus is a Greek name meaning "resolute in contention".[18] The capital Antioch received its name in deference to Antiochus, the father of the Seleucid dynasty's founder Seleucus I;[19] the name became dynastic and many Seleucid kings bore it.[20][21]

Reign

According to Josephus, following the death of his father, Antiochus X went to the city of Aradus where he declared himself king;[22] it is possible that Antiochus IX, before facing Seleucus VI, sent his son to that city for protection.[23] Aradus was an independent city since 137 BC, meaning that Antiochus X made an alliance with it, since he would not have been able to subdue it by force at that stage of his reign.[24] As the descendants of Antiochus VIII and Antiochus IX fought over Syria, they portrayed themselves in the likeness of their respective fathers to indicate their legitimacy; Antiochus X's busts on his coins show him with a short nose that ends with an up-turn, like his father.[25] Ancient Hellenistic kings did not use regnal numbers. Instead, they usually employed epithets to distinguish themselves from other rulers with similar names; the numbering of kings is mostly a modern practice.[26][20] On his coins, Antiochus X appeared with the epithets Eusebes (the pious) and Philopator (father-loving).[27][28] According to Appian, the king received the epithet Eusebes from the Syrians because he escaped a plot on his life by Seleucus VI, and, officially, the Syrians thought that he survived because of his piety, but, in reality, it was a prostitute in love with Antiochus X who saved him.[29]

Beginning his reign in 218 SE (95/94 BC),[23] Antiochus X was deprived of resources and lacked a queen. He therefore married a woman who could provide what he needed, his stepmother Cleopatra Selene.[30] Antiochus X was probably no more than twenty years old while his wife was in her forties.[31] This union was not unprecedented in the Seleucid dynasty, as Antiochus I had married his stepmother Stratonice,[30] but nevertheless, the marriage was scandalous. Appian commented that he thought the real reason behind the epithet "Eusebes" to be a joke by the Syrians, mocking Antiochus X's piety, as he showed loyalty to his father by bedding his widow.[note 3][31] Appian concluded that it was "divine vengeance" for his marriage that eventually led to Antiochus X's fall.[29]

First reign in Antioch

One of Antiochus X's first actions was to avenge his father;[33] in 94 BC, he advanced on the capital Antioch and drove Seleucus VI out of northern Syria into Cilicia.[34] According to Eusebius, the final battle between Antiochus X and Seleucus VI took place near the Cilician city of Mopsuestia,[35] ending in Antiochus X's victory while Seleucus VI took refuge in the city, where he perished as a result of a popular revolt.[34]

During the Seleucid period, currency struck in times of campaigns against a rival or a usurper showed the king bearded,[36] and what seems to be the earliest bronze coinage of Antiochus X shows him with a curly beard,[33] while later currency, apparently meant to show the king in firm control of his realm, depicted Antiochus X clean shaven.[37] Early in 93 BC, the brothers of Seleucus VI, Antiochus XI and Philip I, avenged Seleucus VI by sacking Mopsuestia. Antiochus XI then advanced on Antioch, defeated Antiochus X, and expelled him from the city, reigning alone in the capital for few months.[38]

Second reign in Antioch

Antiochus X recruited new soldiers and attacked Antioch the same year. He emerged victorious, while Antiochus XI drowned in the Orontes River as he tried to flee.[39] Now Antiochus X ruled northern Syria and Cilicia;[37] around this time, Mopsuestia minted coins with the word "autonomous" inscribed. This new political status seems to have been a privilege bestowed upon the city by Antiochus X, who, as a sign of gratitude for Mopsuestia's role in eliminating Seleucus VI, apparently not just rebuilt it, but also compensated it for the damage it suffered at the hands of Seleucus VI's brothers.[40] In the view of the numismatist Hans von Aulock, some coins minted in Mopsuestia may carry a portrait of Antiochus X.[note 4][42] Other cities minted their own civic coinage under the king's rule, including Tripolis, Berytus,[43][44] and perhaps the autonomous city of Ascalon.[note 5][45]

In the capital, Antiochus X might have been responsible for building a library and an attached museum on the model of the Library of Alexandria.[note 6][47] Philip I was probably centered at Beroea; his brother, Demetrius III, who ruled Damascus, supported him and marched north probably in the spring of 93 BC.[48] Antiochus X faced fierce resistance from his cousins.[49] In the year 220 SE (93/92 BC), the city of Damascus stopped issuing coins in the name of Demetrius III, then resumed the following year;[50] this could have been the result of incursions by Antiochus X, which weakened his cousin and made Damascus vulnerable to attacks by the Judaean king Alexander Jannaeus.[51]

Children

The Roman statesman Cicero wrote about two sons of Antiochus X and Cleopatra Selene who visited Rome during his time (between 75 and 73 BC); one of them was named Antiochus.[52] The king might have also fathered a daughter with his wife;[53] according to the first century historian Plutarch, the Armenian king Tigranes II, who killed Cleopatra Selene in 69 BC, "put to death the successors of Seleucus, and [carried] off their wives and daughters into captivity".[53] This statement makes it possible to assume that Antiochus X had at least one daughter with his wife.[54]

- Antiochus XIII: mentioned by Cicero.[55] His epithets raised questions about how many sons with that name Antiochus X fathered;[56] when Antiochus XIII issued coins as a sole ruler, he used the epithet Philadelphos ("brother-loving"), but on jugate coins that show Cleopatra Selene as regent along with a ruling son named Antiochus, the epithet Philometor ("mother-loving") is used.[56] The historian Kay Ehling, agreeing with the view of Bouché-Leclercq, argued that two sons, both named Antiochus, resulted from the marriage of Antiochus X and Cleopatra Selene.[56] Cicero, on the other hand, left one of the brothers unnamed, and clearly stated that Antiochus was the name of only one prince.[52] Ehling's theory is possible but only if "Antiochus Philometor" was the prince named by Cicero, and the brother, who had a different name, assumed the dynastic name Antiochus with the epithet Philadelphos when he became king following the death of Antiochus Philometor.[55] In the view of the historian Adrian Dumitru, such a scenario is complicated; more likely, Antiochus XIII bore two epithets, Philadelphos and Philometor.[55] Several numismatists, such as Oliver D. Hoover, Catharine Lorber and Arthur Houghton, agree that both epithets denoted Antiochus XIII.[57]

- Seleucus VII: the numismatist Brian Kritt deciphered and published a newly discovered jugate coin bearing the portrait of Cleopatra Selene and a co-ruler in 2002.[58][59] Kritt's reading gave the name of King Seleucus Philometor and, considering the epithet which means mother loving, equated him with the unnamed son mentioned by Cicero.[60] Kritt gave the newly discovered king the regnal name Seleucus VII.[61] Some scholars, such as Lloyd Llewellyn Jones and Michael Roy Burgess, accepted the reading,[62][63] but Hoover rejected Kritt's reading as the coin is badly damaged and some of the letters cannot be read. Hoover proposed a different reading where the king's name is Antiochus, to be identified with Antiochus XIII.[59]

- Seleucus Kybiosaktes: the unnamed son mentioned by Cicero does not appear in other ancient literature.[64] Seleucus Kybiosaktes, a man who appeared c. 58 BC in Egypt as a husband of its queen Berenice IV, is identified by modern scholarship with the unnamed prince.[note 7][66] According to the first century BC historian Strabo, Kybiosaktes pretended to be of Seleucid descent.[64] Kritt considered it plausible to identify Seleucus VII with Seleucus Kybiosaktes.[61]

Conflict with Parthia and demise

Information about Antiochus X after the interference of Demetrius III is scanty.[50] Ancient sources and modern scholars present different accounts and dates for the demise of the king.[67][50] Antiochus X's end as told by Josephus, which has the king killed during a campaign against the Parthians, is considered the most reliable and likely by modern historians.[68][65] Towards the end of his reign, Antiochus X increased his coin production, and this could be related to the campaign undertaken by the Seleucid monarch against Parthia, as recorded by Josephus. The Parthians were advancing in eastern Syria in the time of Antiochus X, which would have made it important for the king to counter attack, thus strengthening his position in the war against his cousins.[69] The majority of scholars accept the year 92 BC for Antiochus X's end:[50][70]

Year of death

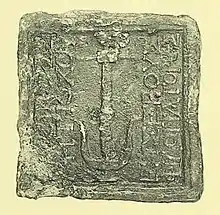

No known coins issued by the king in Antioch contain a date.[71] Josephus wrote that the king fell soon after Demetrius III's interference, but this statement is vague.[50] Most scholars, such as Edward Theodore Newell, understood Josephus's statement to indicate 92 BC. According to Hoover, the dating of Newell is apparently based on combining the statement of Josephus with that of Eusebius, who wrote that Antiochus X was ejected from the capital in 220 SE (93/92 BC) by Philip I. Hoover considered Newell's dating hard to accept; a market weight from Antioch bearing Antiochus X's name, from 92 BC, might contradict the dating of 220 SE (93/92 BC).[50] On the other hand, in the year 221 SE (92/91 BC), the city of Antioch issued civic coinage mentioning no king;[50] Hoover noted that the civic coinage mentions Antioch as the "metropolis" but not as autonomous, and this might be explained as a reward from Antiochus X bestowed upon the city for supporting him in his struggle against his cousins.[note 8][50]

In 2007, using a methodology based on estimating the annual die usage average rate (the Esty formula), Hoover proposed the year 224 SE (89/88 BC) for the end of Antiochus X's reign.[note 9][74] Later in 2011, Hoover noted that this date is hard to accept considering that during Antiochus X's second reign in the capital, only one or two dies were used per year, far too few for the Seleucid average rate to justify a long reign.[75] Hoover then noted that there seem to be several indications that the coinage of Antiochus X's second reign in the capital, along with the coinages of Antiochus XI and Demetrius III, were re-coined by Philip I who eventually took Antioch c. 87 BC, thus explaining the rarity of those kings' coins.[76] Hoover admitted that his conclusion is "troubling".[77] The historian Marek Jan Olbrycht considered Hoover's dating and arguments too speculative, as they contradict ancient literature.[70]

Manner of death

The manner of the king's death varies depending on which ancient account is used. The main ancient historians providing information on Antiochus X's end are Josephus, Appian, Eusebius and Saint Jerome:[78]

The account of Josephus: "For when he was come as an auxiliary to Laodice, queen of the Gileadites, when she was making war against the Parthians, and he was fighting courageously, he fell."[22] The Parthians might have been allied with Philip I.[79] The people of Laodice, their location, and who she was are hard to determine,[80][81] as surviving manuscripts of Josephus's work transmit different names for the people.[68] Gileadites is an older designation based on the Codex Leidensis (Lugdunensis) manuscript of Josephus's work, but the academic consensus uses the designation Sameans,[30] based on the Codex Palatinus (Vaticanus) Graecus manuscript.[68]

- Based on the reading Gileadites: In the view of Bouché-Leclercq, the division of Syria between Antiochus X and his cousins must have tempted the Parthian king Mithridates II to annex the kingdom. Bouché-Leclercq, agreeing with the historian Alfred von Gutschmid, identified the mysterious queen with Antiochus X's cousin Laodice, daughter of Antiochus VIII, and wife of Mithridates I, the king of Commagene, which had recently detached from the Seleucids, and suggested that Laodice resided in Samosata.[82][83] Bouché-Leclercq hypothesized that Antiochus X did not go to help his rivals' sister, but to stop the Parthians before they reached his own borders.[82] The historian Adolf Kuhn, on the other hand, considered it implausible that Antiochus X would support a daughter of Antiochus VIII and he questioned the identification with the queen of Commagene.[note 10][85] Ehling, attempting to explain Antiochus X's assistance of Laodice, suggested that the queen was a daughter of Antiochus IX, a sister of Antiochus X.[49]

- Based on the reading Sameans: the historian Josef Dobiáš considered Laodice a queen of a nomadic tribe based on the similarities between the name from the Codex Palatinus (Vaticanus) Graecus with the Samènes, a people mentioned by the sixth century geographer Stephanus of Byzantium as an Arab nomadic tribe. This would solve the problems posed by the identification with the queen of Commagene, and end the debate regarding the location of the people, as the nature of their nomadic life makes it impossible to determine exactly the place where the fight took place. Dobiáš attributed the initiative to Antiochus X who was not merely trying to defend his borders but actively attacking the Parthians.[86]

The account of Appian: Antiochus X was expelled from Syria by Tigranes II of Armenia.[29] Appian gave Tigranes II a reign of fourteen years in Syria ending in 69 BC.[87] That year witnessed the retreat of the Armenian king due to a war with the Romans. Hence, the invasion of Syria by Tigranes, based on the account of Appian, probably took place in 83 BC.[note 11][87][89] Bellinger dismissed this account, and considered that Appian confused Antiochus X with his son Antiochus XIII.[67] Kuhn considered a confusion between father and son to be out of the question because Appian mentioned the epithet Eusebes when talking about the fate of Antiochus X. In the view of Kuhn, Antiochus X retreated to Cilicia after being defeated by Tigranes II, and his sons ruled that region after him and were reported visiting Rome in 73 BC.[85] However, numismatic evidence proves that Demetrius III controlled Cilicia following the demise of Antiochus X, and that Tarsus minted coins in his name c. 225 SE (88/87 BC).[90] The Egyptologist Christopher J. Bennett, considered it possible that Antiochus X retreated to Ptolemais after being defeated by Tigranes since it became his widow's base.[91] In his history, Appian failed to mention the reigns of Demetrius III and Philip I in the capital which preceded the reign of Tigranes II. According to Hoover, Appian's ignorance of the intervening kings between Antiochus X and Tigranes II might explain how he confused Antiochus XIII, who is known to have fled from the Armenian king, with his father.[92]

Eusebius and others: According to Eusebius, who used the account of the third century historian Porphyry, Antiochus X was ejected from the capital by Philip I in 220 SE (93/92 BC) and fled to the Parthians.[note 12][50][67] Eusebius added that following the Roman conquest of Syria, Antiochus X surrendered to Pompey, hoping to be reinstated on the throne, but the people of Antioch paid money to the Roman general to avoid a Seleucid restoration. Antiochus X was then invited by the people of Alexandria to rule jointly with the daughters of Ptolemy XII, but he died of illness soon after.[65] This account has been questioned by many scholars, such as Hoover and Bellinger.[50][67] The story told by Eusebius contains factual inaccuracies, as he wrote that in the same year Antiochus X was defeated by Philip I, he surrendered to Pompey,[94] while at the same time Philip I was captured by the governor of Syria Aulus Gabinius.[50][95] However, Pompey arrived in Syria only in 64 BC,[96] and left it in 62 BC.[97] Aulus Gabinius was appointed governor of Syria in 57 BC.[98] Also, the part of Eusebius's account regarding the surrender to Pompey echoes the fate of Antiochus XIII;[99] the writer seems to be confusing the fate of Antiochus X with that of his son.[67][71] The second century historian Justin, writing based on the work of the first century BC historian Trogus, also confused the father and son, as he wrote that Antiochus X was appointed king of Syria by the Roman general Lucullus following the defeat of Tigranes II in 69 BC.[92][65]

Succession

It is known from numismatic evidence that Demetrius III eventually succeeded Antiochus X in Antioch.[100] Eusebius's statement that Antiochus X was ejected from the capital by Philip I in 220 SE (93/92 BC) is contradicted by the coins of Demetrius III, who was not mentioned at all by Eusebius.[50] Any suggestions that Philip I controlled Antioch before the demise of Demetrius III can be dismissed; in addition to the numismatic evidence, no ancient source claimed that Demetrius III had to push Philip I out of the city.[74]

In 1949, a jugate coin of Cleopatra Selene and Antiochus XIII, from the collection of the French archaeologist Henri Arnold Seyrig, was dated by the historian Alfred Bellinger to 92 BC and ascribed to Antioch.[67] Based on Bellinger's dating, some modern historians, such as Ehling, proposed that Cleopatra Selene enjoyed an ephemeral reign in Antioch between the death of her husband and the arrival of his successor.[101] Bellinger doubted his own dating and the coin's place of issue in 1952, suggesting Cilicia instead of Antioch.[56] This coin is dated by many twenty-first century scholars to 82 BC.[101]

Notes

- Some dates in the article are given according to the Seleucid era, which is indicated when two years have a slash separating them. Each Seleucid year started in the late autumn of a Gregorian year; a Seleucid year thus overlaps two Gregorian ones.[1]

- The 6th-century monk and historian John Malalas wrote that following the war between Antiochus VII and Parthia, a daughter of the Parthian king, named Brittane, was married to Antiochus IX, Antiochus VII's son, to end the conflict.[12] The work of Malalas is considered generally unreliable by scholars,[13] but 16 or 17 years separate the death of Cleopatra IV and the marriage of Antiochus IX and Cleopatra Selene; it would be very strange for the king to have remained unmarried throughout this period.[14]

- Modern historians David Levenson and Thomas Martin explained the epithet Eusebes as an official title of the king that was later used by the Syrians to mock him, which gave rise to the story told by Appian.[32]

- Several factors support assigning the portrait on the autonomous coins to Antiochus X. First, the city was anti-Seleucus VI, and the aforementioned king was defeated by Antiochus X, making it logical to assume that the latter was the monarch who gave the city its autonomy. Second, two of those coins bear what seems to be the monogram AKZ, which translates to the Seleucid year 224, i.e. 89/88 BC Gregorian, but the monogram is not securely read. This year is within the reign span of Antiochus X. Von Aulock did not affirm the attribution, and left the space open for the possibility that the king depicted is Seleucus VI, or maybe not even a Syrian king altogether.[41] The portrait could be that of a god or a hero instead.[42]

- Ascalon, though not under the direct authority of the Seleucids, minted coinage bearing royal portraits; a coin dating to year 12 of Ascalon's autonomy, 222 SE (91/90 BC), bears a royal portrait resembling that of Antiochus X, and the numismatist Arnold Spaer suggested that it is possible, although he did not affirm it.[45]

- The builder could also be Antiochus IX; according to Malalas, king Antiochus Philopator built the library with the money left for that purpose by a Syrian merchant named Maron who died in Athens. Three Seleucid kings bore the epithet Philopator: Antiochus IX, Antiochus X and Antiochus XII; the latter can not be the builder since he only ruled Damascus and never took control of Antioch.[46]

- According to the second century historian Cassius Dio, a "Seleucus", who in 58 BC became a husband of Berenice IV, was killed by his wife.[64] The first century BC historian Strabo talks about a man, bearing the epithet "Kybiosaktes" ("salt-fish dealer"), who claimed to be a Seleucid prince, and married Berenice IV who eventually killed him.[64] According to Eusebius, who used the work of the third century historian Porphyry as a source, Antiochus X himself attempted to marry Berenice IV but died of a sudden illness.[65] Combining the accounts of Cassius Dio and Strabo, the historian Alfred Bellinger named the Seleucid husband of Berenice IV "Seleucus Kybiosaktes".[64] The similarities of the accounts of Dio Cassius and Strabo indicate that the same character was the subject of those classical accounts; modern scholars identify Antiochus X and Cleopatra Selene's unnamed son with Seleucus Kybiosaktes.[60]

- The civic coins were made of bronze and were minted until 69 BC; they were produced alongside royal coins, evidenced by the coins of Antiochus X's successors in the city, Demetrius III and Philip I, which were made of silver, indicating that issuing silver coinage remained a royal privilege.[72]

- The Esty formula was developed by the mathematician Warren W. Esty; it is a mathematical formula that can calculate the relative number of obverse dies used to produce a certain coin series. The calculation can be used to measure the coinage's production of a certain king and thus estimate the length of his reign.[73]

- The Codex Leidensis (Lugdunensis) manuscript have Γαλιχηνών (which was rendered as Gileadites by the seventeenth century historian William Whiston in his English translation of the work of Josephus) as the name of Laodice's people.[30][22] The name from the manuscript is obviously damaged and altered; von Gutschmid identified the Laodice mentioned by Josephus with the queen of Commagene and corrected Gilead to Kαλλινιχηνών (the people of Callinicos, i.e. modern Raqqa).[84][83] Kuhn, citing the archaeologist Otto Puchstein's rejection of von Gutschmid's identification, questioned von Gutschmid's reading of Kαλλινιχηνών, and noted that the name came to designate Raqqa at a much later date than the period of Antiochus X.[85] The historian Josef Dobiáš noted that regardless of when Callinicos started to be applied to Raqqa, it is doubtful that the city belonged to Commagene at all.[86]

- Eusebius gave Tigranes a reign of seventeen years in Syria, thus, according to this account, Tigranes conquered the country in 86 BC.[87] Based on several arguments contradicting Appian's account, Hoover suggested that Tigranes invaded Syria only in 74 BC.[88]

- In the view of the numismatist Edgar Rogers, Philip I was able to rule Antioch immediately after Antiochus XI,[93] but it cannot be maintained that Philip I held the capital at any time before the demise of his cousin Antiochus X and his brother Demetrius III; this would contradict both the numismatic evidence and ancient literature, since no source indicates that Demetrius III pushed Philip I out of Antioch.[74]

References

Citations

- Biers 1992, p. 13.

- Marciak 2017, p. 8.

- Goodman 2005, p. 37.

- Kelly 2016, p. 82.

- Wright 2005, p. 76.

- Kosmin 2014, p. 23.

- Grainger 1997, p. 32.

- Grainger 1997, p. 33.

- Tinsley 2006, p. 179.

- Bouché-Leclercq 1913, p. 418.

- Whitehorne 2002, p. 165.

- Malalas 1940, p. 19.

- Scott 2017, p. 76.

- Ogden 1999, p. 156.

- Bouché-Leclercq 1913, pp. 641, 643, 416.

- Bennett 2002a, p. note 4.

- Bennett 2002, p. note 14.

- Ross 1968, p. 47.

- Downey 2015, p. 68.

- Hallo 1996, p. 142.

- Taylor 2013, p. 163.

- Josephus 1833, p. 421.

- Dumitru 2016, p. 262.

- Bellinger 1949, p. 74.

- Wright 2011, p. 46.

- McGing 2010, p. 247.

- Green 1990, p. 552.

- Leake 1854, p. 36.

- Appian 1899, p. 324.

- Dumitru 2016, p. 264.

- Whitehorne 2002, p. 168.

- Levenson & Martin 2009, p. 334.

- Lorber & Iossif 2009, p. 102.

- Houghton 1989, p. 97.

- Eusebius 1875, p. 259.

- Lorber & Iossif 2009, p. 112.

- Lorber & Iossif 2009, p. 103.

- Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 573.

- Ehling 2008, p. 239.

- Sayar, Siewert & Taeuber 1994, pp. 127, 128.

- Von Aulock 1963, pp. 233, 234.

- Rigsby 1996, p. 471.

- Mørkholm 1984, p. 100.

- Murray 1991, p. 54.

- Spaer 1984, p. 230.

- Downey 2015, p. 132.

- Sartre 2003, p. 295.

- Ehling 2008, pp. 239, 241.

- Ehling 2008, p. 241.

- Hoover 2007, p. 290.

- Atkinson 2016, p. 127.

- Dumitru 2016, p. 268.

- Dumitru 2016, pp. 269, 270.

- Dumitru 2016, p. 270.

- Dumitru 2016, p. 269.

- Dumitru 2016, p. 267.

- Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 618.

- Kritt 2002, p. 25.

- Hoover 2005, p. 95.

- Kritt 2002, p. 27.

- Kritt 2002, p. 28.

- Llewellyn Jones 2013, p. 1573.

- Burgess 2004, p. 20.

- Kritt 2002, p. 26.

- Dumitru 2016, p. 265.

- Kritt 2002, pp. 26, 27.

- Bellinger 1949, p. 75.

- Olbrycht 2009, p. 166.

- Overtoom 2020, p. 270.

- Olbrycht 2009, p. 181.

- Schürer 1973, p. 135.

- Dumitru 2016, pp. 266, 267.

- Hoover 2007, pp. 282–284.

- Hoover 2007, p. 294.

- Hoover 2011, p. 259.

- Hoover 2011, pp. 259–262.

- Hoover 2011, p. 265.

- Hoover 2007, pp. 290–292.

- Wright 2011, p. 12.

- Sievers 1986, p. 134.

- Dumitru 2016, pp. 264, 266.

- Bouché-Leclercq 1913, p. 421.

- Von Gutschmid 1888, p. 80.

- Dobiáš 1931, pp. 222–223.

- Kuhn 1891, p. 36.

- Dobiáš 1931, p. 223.

- Sayar, Siewert & Taeuber 1994, p. 128.

- Hoover 2007, p. 297.

- Brennan 2000, p. 410.

- Lorber & Iossif 2009, pp. 103, 104.

- Bennett 2002a, p. note 31.

- Hoover 2007, p. 291.

- Rogers 1919, p. 32.

- Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 565.

- Eusebius 1875, p. 261.

- Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 566.

- Burns 2007, p. 46.

- Downey 2015, p. 148.

- Hoover 2007, p. 292.

- Hoover 2007, p. 295.

- Dumitru 2016, p. 266.

Sources

- Appian (1899) [c. 150]. The Roman History of Appian of Alexandria. Vol. I: The Foreign Wars. Translated by White, Horace. The Macmillan Company. OCLC 582182174.

- Atkinson, Kenneth (2016). A History of the Hasmonean State: Josephus and Beyond. T&T Clark Jewish and Christian Texts. Vol. 23. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-66903-2.

- Bellinger, Alfred R. (1949). "The End of the Seleucids". Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. 38. OCLC 4520682.

- Bennett, Christopher J. (2002). "Cleopatra IV". C. J. Bennett. The Egyptian Royal Genealogy Project hosted by the Tyndale House Website. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Bennett, Christopher J. (2002a). "Cleopatra Selene". C. J. Bennett. The Egyptian Royal Genealogy Project hosted by the Tyndale House Website. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Biers, William R. (1992). Art, Artefacts and Chronology in Classical Archaeology. Approaching the Ancient World. Vol. 2. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06319-7.

- Bouché-Leclercq, Auguste (1913). Histoire Des Séleucides (323–64 avant J.-C.) (in French). Ernest Leroux. OCLC 558064110.

- Brennan, T. Corey (2000). The Praetorship in the Roman Republic. Vol. 2: 122 to 49 BC. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511460-7.

- Burgess, Michael Roy (2004). "The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress– The Rise and Fall of Cleopatra II Selene, Seleukid Queen of Syria". The Celator. Kerry K. Wetterstrom. 18 (3). ISSN 1048-0986.

- Burns, Ross (2007) [2005]. Damascus: A History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-48849-0.

- Dobiáš, Josef (1931). "Les Premiers Rapports des Romains avec les Parthes et L'occupation de la Syrie". Archiv Orientální (in French). Czechoslovak Oriental Institute. 3. ISSN 0044-8699.

- Downey, Robert Emory Glanville (2015) [1961]. A History of Antioch in Syria from Seleucus to the Arab Conquest. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7773-7.

- Dumitru, Adrian (2016). "Kleopatra Selene: A Look at the Moon and Her Bright Side". In Coşkun, Altay; McAuley, Alex (eds.). Seleukid Royal Women: Creation, Representation and Distortion of Hellenistic Queenship in the Seleukid Empire. Historia – Einzelschriften. Vol. 240. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 253–272. ISBN 978-3-515-11295-6. ISSN 0071-7665.

- Ehling, Kay (2008). Untersuchungen Zur Geschichte Der Späten Seleukiden (164–63 v. Chr.) Vom Tode Antiochos IV. Bis Zur Einrichtung Der Provinz Syria Unter Pompeius. Historia – Einzelschriften (in German). Vol. 196. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-09035-3. ISSN 0071-7665.

- Eusebius (1875) [c. 325]. Schoene, Alfred (ed.). Eusebii Chronicorum Libri Duo (in Latin). Vol. 1. Translated by Petermann, Julius Heinrich. Apud Weidmannos. OCLC 312568526.

- Goodman, Martin (2005) [2002]. "Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period". In Goodman, Martin; Cohen, Jeremy; Sorkin, David Jan (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 36–52. ISBN 978-0-19-928032-2.

- Grainger, John D. (1997). A Seleukid Prosopography and Gazetteer. Mnemosyne, Bibliotheca Classica Batava. Supplementum. Vol. 172. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-10799-1. ISSN 0169-8958.

- Green, Peter (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Vol. 1. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08349-3. ISSN 1054-0857.

- Hallo, William W. (1996). Origins. The Ancient Near Eastern Background of Some Modern Western Institutions. Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 6. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10328-3. ISSN 0169-9024.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2005). "Dethroning Seleucus VII Philometor (Cybiosactes): Epigraphical Arguments Against a Late Seleucid Monarch". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH. 151. ISSN 0084-5388.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2007). "A Revised Chronology for the Late Seleucids at Antioch (121/0–64 BC)". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. Franz Steiner Verlag. 56 (3): 280–301. doi:10.25162/historia-2007-0021. ISSN 0018-2311. S2CID 159573100.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2011). "A Second Look at Production Quantification and Chronology in the Late Seleucid Period". In de Callataÿ, François (ed.). Time is Money? Quantifying Monetary Supplies in Greco-Roman Times. Pragmateiai. Vol. 19. Edipuglia. pp. 251–266. ISBN 978-8-872-28599-2. ISSN 2531-5390.

- Houghton, Arthur (1987). "The Double Portrait Coins of Antiochus XI and Philip I: a Seleucid Mint at Beroea?". Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau. Schweizerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft. 66. ISSN 0035-4163.

- Houghton, Arthur (1989). "The Royal Seleucid Mint of Seleucia on the Calycadnus". In Le Rider, Georges Charles; Jenkins, Kenneth; Waggoner, Nancy; Westermark, Ulla (eds.). Kraay-Mørkholm Essays. Numismatic Studies in Memory of C.M. Kraay and O. Mørkholm. Numismatica Lovaniensia. Vol. 10. Université Catholique de Louvain: Institut Supérieur d'Archéologie et d'Histoire de l'Art. Séminaire de Numismatique Marcel Hoc. pp. 77–98. OCLC 910216765.

- Houghton, Arthur; Lorber, Catherine; Hoover, Oliver D. (2008). Seleucid Coins, A Comprehensive Guide: Part 2, Seleucus IV through Antiochus XIII. Vol. 1. The American Numismatic Society. ISBN 978-0-9802387-2-3. OCLC 920225687.

- Josephus (1833) [c. 94]. Burder, Samuel (ed.). The Genuine Works of Flavius Josephus, the Jewish Historian. Translated by Whiston, William. Kimber & Sharpless. OCLC 970897884.

- Kelly, Douglas (2016). "Alexander II Zabinas (Reigned 128–122)". In Phang, Sara E.; Spence, Iain; Kelly, Douglas; Londey, Peter (eds.). Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia (3 Vols.). Vol. I. ABC-CLIO. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-61069-020-1.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

- Kritt, Brian (2002). "Numismatic Evidence for a New Seleucid King: Seleucus (VII) Philometor". The Celator. Kerry K. Wetterstrom. 16 (4). ISSN 1048-0986.

- Kuhn, Adolf (1891). Beiträge zur Geschichte der Seleukiden vom Tode Antiochos VII. Sidetes bis auf Antiochos XIII. Asiatikos 129–64 V. C (in German). Altkirch i E. Buchdruckerei E. Masson. OCLC 890979237.

- Leake, William Martin (1854). Numismata Hellenica: a Catalogue of Greek Coins. John Hearne. OCLC 36274386.

- Levenson, David B.; Martin, Thomas R. (2009). "Akairos or Eukairos? The Nickname of the Seleucid King Demetrius III in the Transmission of the Texts of Josephus' War and Antiquities". Journal for the Study of Judaism. Brill. 40 (3). ISSN 0047-2212.

- Llewellyn Jones, Lloyd (2013) [2012]. "Cleopatra Selene". In Bagnall, Roger S.; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B.; Erskine, Andrew; Huebner, Sabine R. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Ancient History (13 Vols.). Vol. III: Be-Co. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 1572–1573. ISBN 978-1-4051-7935-5.

- Lorber, Catharine C.; Iossif, Panagiotis (2009). "Seleucid Campaign Beards". L'Antiquité Classique. l’asbl L’Antiquité Classique. 78. ISSN 0770-2817.

- Malalas, John (1940) [c. 565]. Chronicle of John Malalas, Books VIII–XVIII. Translated from the Church Slavonic. Translated by Spinka, Matthew; Downey, Glanville. University of Chicago Press. OCLC 601122856.

- Marciak, Michał (2017). Sophene, Gordyene, and Adiabene. Three Regna Minora of Northern Mesopotamia Between East and West. Impact of Empire. Vol. 26. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-35070-0. ISSN 1572-0500.

- McGing, Brian C. (2010). Polybius' Histories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971867-2.

- Mørkholm, Otto (1984). "The Monetary System in the Seleucid Empire After 187 B.C.". In Heckel, Waldemar; Sullivan, Richard (eds.). Ancient Coins of the Graeco-Roman World: The Nickle Numismatic Papers. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-130-9.

- Murray, William M. (1991). "The Provenance and Date: The Evidence of the Symbols". In Casson, Lionel; Steffy, Richard (eds.). The Athlit Ram. Ed Rachal Foundation Nautical Archaeology Series. Vol. 3. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-451-4.

- Ogden, Daniel (1999). Polygamy, Prostitutes and Death: The Hellenistic Dynasties. Duckworth with the Classical Press of Wales. ISBN 978-0-7156-2930-7.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2009). "Mithridates VI Eupator and Iran". In Højte, Jakob Munk (ed.). Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Black Sea Studies. Vol. 9. Aarhus University Press. pp. 163–190. ISBN 978-8-779-34443-3. ISSN 1903-4873.

- Overtoom, Nikolaus Leo (2020). Reign of Arrows: The Rise of the Parthian Empire in the Hellenistic Middle East. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190-88834-3.

- Rigsby, Kent J. (1996). Asylia: Territorial Inviolability in the Hellenistic World. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Vol. 22. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20098-2.

- Rogers, Edgar (1919). "Three Rare Seleucid Coins and their Problems". The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. fourth. Royal Numismatic Society. 19. ISSN 2054-9199.

- Ross, Alan S. C. (1968). "Aldrediana XX: Notes on the Preterite-Present Verbs". English Philological Studies. W. Heffer & Sons, Ltd for the University of Birmingham. 11. ISSN 0308-0129.

- Sartre, Maurice (2003) [2001]. D'Alexandre à Zénobie: Histoire du Levant Antique, IVe Siècle Avant J.-C. – IIIe Siècle Après J.-C (in French) (nouvelle édition revue et mise à jour ed.). Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-60921-8.

- Sayar, Mustafa; Siewert, Peter; Taeuber, Hans (1994). "Asylie-Erklärungen des Sulla und des Lucullus für das Isis- und Sarapisheiligtum von Mopsuhestia (Ostkilikien)". TYCHE: Beiträge zur Alten Geschichte, Papyrologie und Epigraphik (in German). Universität Wien. Verlag A. Holzhauscns. 9. ISSN 1010-9161.

- Schürer, Emil (1973) [1874]. Vermes, Geza; Millar, Fergus; Black, Matthew (eds.). The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ. Vol. I (2014 ed.). Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 978-1-4725-5827-5.

- Scott, Roger (2017) [1989]. "Malalas and his Contemporaries". In Jeffreys, Elizabeth; Croke, Brian; Scott, Roger (eds.). Studies in John Malalas. Byzantina Australiensia. Vol. 6. Brill. pp. 67–85. ISBN 978-9-004-34462-4.

- Sievers, Joseph (1986). "Antiochus X". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 2. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-9110-9. ISSN 2330-4804.

- Spaer, Arnold (1984). "Ascalon: From Royal Mint to Autonomy". In Houghton, Arthur; Hurter, Silvia; Mottahedeh, Patricia Erhart; Scott, Jane Ayer (eds.). Festschrift Für Leo Mildenberg: Numismatik, Kunstgeschichte, Archäologie = Studies in Honor of Leo Mildenberg: Numismatics, Art History, Archeology. Wetteren: Editions NR. ISBN 978-9-071-16501-6.

- Tinsley, Barbara Sher (2006). Reconstructing Western Civilization: Irreverent Essays on Antiquity. Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-1-57591-095-6.

- Von Aulock, Hans (1963). "Die Münzprägungen der kilikischen Stadt Mopsos". Archäologischer Anzeiger (in German). Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. 78. ISSN 0003-8105.

- Von Gutschmid, Alfred (1888). Nöldeke, Theodor (ed.). Geschichte Irans und seiner Nachbarländer von Alexander dem Grossen bis zum Untergang der Arsaciden (in German). Verlag der H. Laupp'schen Buchhandlung. OCLC 4456690.

- Taylor, Michael J. (2013). Antiochus the Great. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84884-463-6.

- Whitehorne, John (2002) [1994]. Cleopatras. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05806-3.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2005). "Seleucid Royal Cult, Indigenous Religious Traditions and Radiate Crowns: The Numismatic Evidence". Mediterranean Archaeology. Sydney University Press. 18. ISSN 1030-8482.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2011). "The Iconography of Succession Under the Late Seleukids". In Wright, Nicholas L. (ed.). Coins from Asia Minor and the East: Selections from the Colin E. Pitchfork Collection. The Numismatic Association of Australia. ISBN 978-0-646-55051-0.

External links

- Antiochus X's recently discovered coin (after 2008) in "The Seleucid Coins Addenda System (SCADS)" website maintained by Oliver D. Hoover. Exhibiting what might be the king's first coin bearing a date, 221 SE (92/91 BC).

- Antiochus X's recently discovered coin (after 2008) in "The Seleucid Coins Addenda System (SCADS)" website maintained by Oliver D. Hoover. Exhibiting the king's first known coin minted in Tarsus.

- The coin (SNG Levante 1306) possibly depicting Antiochus X from Mopsuestia in "The Seleucid Coins Addenda System (SCADS)" website maintained by Oliver D. Hoover.

- The coin possibly dating to 221 SE (92/91 BC) exhibited in the blog of the numismatist Jayseth Guberman.