Louis François Antoine Arbogast

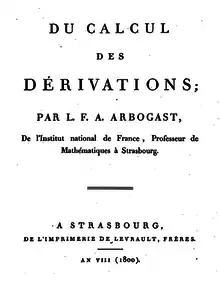

Louis François Antoine Arbogast (4 October 1759 – 8[1] April 1803) was a French mathematician. He was born at Mutzig in Alsace and died at Strasbourg, where he was professor. He wrote on series and the derivatives known by his name: he was the first writer to separate the symbols of operation from those of quantity, introducing systematically the operator notation DF for the derivative of the function F.[3] In 1800, he published a calculus treatise[4] where the first known[5] statement of what is currently known as Faà di Bruno's formula appears, 55 years before the first published paper[6] of Francesco Faà di Bruno on that topic.

Louis François Antoine Arbogast | |

|---|---|

| Born | 4 October 1759 |

| Died | 18 April 1803 (aged 43)[1] |

| Nationality | French |

| Awards | 1789 Prize of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences[2] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematical analysis |

| Institutions | Collège de Colmar, École d'Artillerie de Strasbourg, Université de Strasbourg |

Biography

He was professor of mathematics at the Collège de Colmar and entered a mathematical competition run by the St Petersburg Academy. His entry was to bring him fame and an important place in the history of the development of the calculus. Arbogast submitted an essay to the St Petersburg Academy in which he came down firmly on the side of Euler. In fact he went much further than Euler in the type of arbitrary functions introduced by integrating partial differential equations,[7] claiming that the functions could be discontinuous not only in the limited sense claimed by Euler, but discontinuous in a more general sense that he defined that allowed the function to consist of portions of different curves. Arbogast won the prize with his essay and his notion of discontinuous function became important in Cauchy's more rigorous approach to analysis.

In 1789 he submitted in Strasbourg a major report on the differential and integral calculus to the Académie des Sciences in Paris which was never published. In the Preface of a later work he described the ideas that prompted him to write the major report of 1789. Essentially he realised that there was no rigorous methods to deal with the convergence of series, and Arbogast's career reached new heights. In addition to his mathematics post, he was appointed as professor of physics at the Collège Royal in Strasbourg and from April 1791 he served as its rector until October 1791 when he was appointed rector of the University of Strasbourg; in 1794 he was appointed Professor of Calculus at the École centrale des travaux publics et militarisée (soon to become École Polytechnique) but he taught at the École préparatoire.

His contributions to mathematics show him as a philosophical thinker. As well as introducing discontinuous functions, as we discussed above, he conceived the calculus as operational symbols. The formal algebraic manipulation of series investigated by Lagrange and Laplace in the 1770s has been put in the form of operator equalities by Arbogast in 1800. We owe him the general concept of factorial as a product of a finite number of terms in arithmetic progression.

The original version of this article was taken from the public domain resource the Rouse History of Mathematics.

Notes

- The secondary literature leaves some uncertainty on the death date: some sources report 8 April instead of 18 April. It is possible that in reference Rouse Ball 1960, p. 330 the 1 has been lost as a result of a typographical error: however, the version given by the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive is believed to be the correct one. In fact, the confusion may come from the fact that his death was registered, in the Republican calendar, as 18 Germinal Year XI, which translates to 8 April 1803. See his death certificate in the Archives du Bas-Rhin, document 1273

- According to Taton (1970, p. 259), which mention the mathematician and a few of his achievements while describing the history of scientific relationships between France and Russia.

- See reference Cajori (2007).

- See reference Arbogast 1800.

- According to the accurate analysis of Craik (2005).

- Precisely the paper Faà di Bruno 1855.

- See Michaud & Michaud (1811, p. 362): according to this source, he submitted his memoir in 1792.

References

General references

- Birembaut, Arthur (1959), "Les deux déterminations de l'unité de masse du système métrique", Revue d'histoire des sciences et de leurs applications (in French), 12 (1): 25–54, doi:10.3406/rhs.1959.3698 Available from Persee.

- Cajori, F. (2007) [1929], A History oh Mathematical Notations, Volume II (4th ed.), New York: Cosimo classics, pp. xxii+367, ISBN 978-1-60206-714-1

- Fréchet, M. (1940), "Biographie du mathématicien alsacien Arbogast", Thalès (in French), 4: 43–55, MR 0021505, Zbl 0061.00509.

- Lusternik, L. A.; Petrova, S. S. (1972), "Les premières étapes du calcul symbolique", Revue d'histoire des sciences et de leurs applications (in French), 25 (3): 201–206, doi:10.3406/rhs.1972.3289, MR 0449994, Zbl 0238.01016. Available from Persee.

- Michaud, Joseph Fr.; Michaud, Louis Gabriel, eds. (1811), "Arbogast (Luis-François-Antoine)", Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne; ou, Histoire, par ordre alphabétique: de la vie publique et privée de tous les hommes qui se sont fait remarquer par leurs écrits, leurs actions, leurs talents, leurs vertus ou leurs crimes. (in French), vol. Tome Deuxieme, Paris: Chez Michaud Frères, pp. 361–362. Maybe the earliest biography of Arbogast, printed only few years after his death. Entirely freely available from Google books.

- Rouse Ball, W. W. (1960) [1908], A Short Account of the History of Mathematics (4th ed.), New York: Dover Publications, pp. xxiv+522, ISBN 0-486-20630-0, JFM 20.0001.01 (Review of the first edition), available from Project Gutenberg.

- Taton, René (1970), "Sur l'histoire des relations scientifiques franco-russes", Revue d'histoire des sciences et de leurs applications (in French), 23 (3): 257–264, doi:10.3406/rhs.1970.3145 Available from Persee.

- Voltz, René (October 2001), "L'Université Royale Française (18ème siècle)" (PDF), in Kraus, I.; Mayet, N. (eds.), La Physique à Strasbourg. Regards sur le passé (1621–1918) (in French), retrieved February 26, 2011.

Scientific references

- Arbogast, L. F. A. (1800), Du calcul des derivations (in French), Strasbourg: Levrault, pp. xxiii+404, Entirely freely available from Google books.

- Craik, Alex D. D. (February 2005), "Prehistory of Faà di Bruno's Formula", American Mathematical Monthly, 112 (2): 217–234, doi:10.2307/30037410, JSTOR 30037410, MR 2121322, Zbl 1088.01008.

- Faà di Bruno, F. (1855), "Sullo sviluppo delle funzioni (On the development of the functions)", Annali di Scienze Matematiche e Fisiche (Annals of Mathematics and Physics) (in Italian), 6: 479–480. A well-known paper where Francesco Faà di Bruno presents the two versions of the formula that now bears his name, published in the journal founded by Barnaba Tortolini.

Further reading

- A Short Account of the History of Mathematics at Project Gutenberg

- Itard, Jean (1970), "Arbogast, Louis François Antoine", Dictionary of Scientific Biography, vol. 1, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 206–208, ISBN 0-684-10114-9.