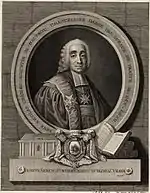

Antoine-François Bertrand de Molleville

Comte Antoine-François Bertrand de Molleville (20 October 1746, Toulouse ~ 30 December 1818, Paris) was a French politician.

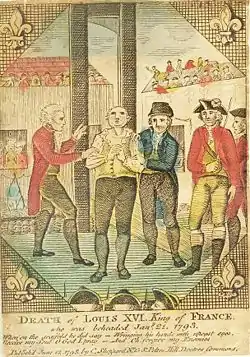

He was considered a fiery partisan of royalty,[1] and surnamed the enfant terrible of the monarchy. He was first conseiller to the Parlement de Toulouse in 1766, then maîtres des requêtes in 1774 and finally Intendant de Bretagne, in 1784. Bertrand de Molleville was then charged in 1788 with the difficult task of dissolving the Parliament of Brittany. Favourable to the gathering of the estates general in 1789, he advised Louis XVI after the dissolution of the Assemblée. Made ministre de la Marine et des Colonies from 1790 to 1792, he organised the mass emigration of officers. Due to numerous denunciations, he retired from his functions and became chief of the royal secret police. Before and after the 10 August 1792, he tried to organise an escape for the king, but he was eventually forced to resolve to flee to England himself. Despite his dedication and his friendship for, he was one of his most untalented servants.[2]

Family

Life

Youth

Antoine-François Bertrand de Molleville was received as a conseiller to the Parlement de Toulouse in 1766.

His secretary was Bernard François Balssa, father of Honoré de Balzac, still in de Moleville's service in 1771.

Antoine-François Bertrand de Molleville served his apprentice in the school of minister Maupeou. He was maîtres des requêtes in 1774.[3]

In 1775 Bertrand de Molleville defended the memoir of his ancestor chancellor Jean Bertrand, seigneur de Frazin,[4] attacked by Condorcet in his Éloge du chancelier de L'Hôpital, but he only published this apology after having communicated it to Condorcet lui-même.[5]

Antoine-François Bertrand de Molleville was made Intendant de Bretagne in 1784.

Intendant de Bretagne (1784-89)

In 1788, along with the Commander of Rennes, Governor Molleville went to Brittany to announce the royal edict that the Breton Parliament was abolished. The entire town turned out, and rumors began to spread that it wasn't a royal edict but a power move by the governor. Fighting broke out, civilians fighting soldiers, and rioters were able to get a noose around Molleville's neck, but he was saved at the last second by the Commander throwing down his sword into the street, saying he refused to fight the people, and by fraternizing with the masses, cooling tensions and saving the governor.[6] Later in the same year, when the Pont Neuf was covered in troops preparing for the Revolution, he remarked he saw "those who later on took part in all the popular movements of the Revolution."[7]

Minister for the Fleet and the Colonies

The Royalist secret police

After the day of 10 August 1792

On his death in 1818 he was buried in the church of Ponsan-Soubiran.

Sources

- Histoire de la Révolution française by Jules Michelet

- Lapeyre et Rémy Scheurer, Les notaires et secrétaires du roi sous les règnes de L. XI, Ch. VIII et L. XII (1461–1515), Tome 2. Paris, 1978, in-4, 91 tablx, B.n.F. : 4° L45. (4-II)

- Gustave Louis Chaix d'Est-Ange, Dictionnaire des familles anciennes ou notables à la fin du XIXe siècle, Évreux, 1903–1929, 20 vol. in-8, e, tome : 4, p. 148 et suivantes, B.n.F. : 8° Lm1. 164

- Jules Villain, La France moderne, tome : 3, B.n.F. : 4° Lm1. 180

- Le Père Anselme, Histoire de la maison royale de France et des grands officiers de la couronne, 3e éd. Paris, 1726–1733, 9 vol. in-fol, tome : 6, B.n.F. : Fol. Lm3. 398.

- Marquis d’Aubais, Pièces fugitives pour servir à l’histoire de France, Paris, 1759, 2 vol. in-4 (t. I, 2e partie, et t. II), tome : 2, B.n.F. : 4° L46. 11,

- Waroquier de Combles, État de la France, ou les vrais marquis, comtes..., Paris, 1783–1785, 2 vol. in-12, tome : 2, 168-9, B.n.F. : 8° Lm1. 34

- Waroquier de Combles, Tableau généalogique et historique de la noblesse, Paris, 1786–1789, 9 vol. in-12, tome : 5, B.n.F. : 8° Lm1. 38

References

- Peter Kropotkin (1909). "Chapter 30". The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793. Translated by N. F. Dryhurst. New York: Vanguard Printings.

Lack of cohesion in the royalist Ministry, one of its members, Bertrand de Moleville, being strongly opposed to the constitutional régime, whilst Narbonne wanted to make it one of the props to the throne, had led to its fall; whereupon, in March 1792, Louis XVI called into power a Girondist Ministry, with Dumouriez for foreign affairs, Roland, that is to say, Madame Roland, for the Interior, Grave, soon to be replaced by Servan, at the War Office, Clavière for Finance, Duranthon for justice, and Lacoste for the Marine.

- Dictionnaire de la conversation et de la lecture inventaire raisonné des ..., de William Duckett, p.98.

- BALZAC and the vallée du VIAUR.

- Biographie nouvelle des contemporains, d'Antoine-Vincent Arnault, p.448.

- France, dictionnaire encyclopédique, de Philippe Le Bas, p.472, and Biographie nouvelle des contemporains, de Antoine-Vincent Arnault, p.448.

- Peter Kropotkin (1909). "Chapter 5". The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793. Translated by N. F. Dryhurst. New York: Vanguard Printings.

- Peter Kropotkin (1909). "Chapter 5". The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793. Translated by N. F. Dryhurst. New York: Vanguard Printings.

- Ferstel, Louis. Histoire de la responsabilité criminelle..., p.54

External links

- (in French) Subdelegates and Subdelegations on the territory of the département, under the ancien régime

- (in French) Letter from the king, to the Assemblée nationale, in reply to the observations addressed to his majesty on the conduct of M. Bertrand, minister for the navy. Letter from M. de Bertrand to the king

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)