Antonia of Württemberg

Antonia of Württemberg (24 March 1613 – 1 October 1679) was a princess of the Duchy of Württemberg, as well as a literary figure, patroness, and Christian Kabbalist.

Antonia of Württemberg | |

|---|---|

Antonia of Württemberg | |

| Born | 24 March 1613 Stuttgart, Germany |

| Died | 1 October 1679 (aged 66) Bad Liebenzell, Germany |

| Noble family | House of Württemberg |

| Father | John Frederick of Württemberg |

| Mother | Barbara Sophie of Brandenburg |

Life

Born in Stuttgart in 1613, Princess Antonia was the third of nine children from the marriage of Duke Johann Frederick of Württemberg and Barbara Sophie of Brandenburg, the daughter of the Elector Joachim Frederick of Brandenburg. Highly educated and generous, she was the sister of Duke Eberhard III of Württemberg, who more than his father played an important role in the Thirty Years War.[1]

During the course of the war many churches in Württemberg were looted and became stripped of their ornaments, especially following the battle of Nördlingen in 1634. Antonia made it her mission to establish foundations to repair and restore the churches. Her charity, piety, gift for languages and all-encompassing scholarship were widely praised, and she became celebrated as "Princess Antonia the learned", and "the Minerva of Württemberg". Wherever possible she dedicated herself to the arts and sciences, together with her two sisters the princesses Anna Johanna and Sibylle.[1]

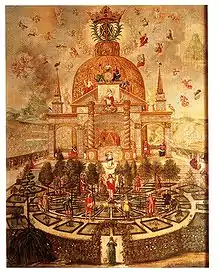

The soul stands at the threshold of the garden of paradise, depicted in a dense web of esoteric symbolic imagery.

She became a close associate of the evangelical Protestant theologian and mystical symbolist Johann Valentin Andreae, and later was on friendly terms with the founder of the Pietism movement, Philip Jacob Spener. In addition to painting, her interests were above all in the realm of philosophy and languages, with a special preference for Hebrew, and the study of the Jewish Kabbalah.[1] Her specifically Christian expression of this tradition found its culmination in the unique large Kabbalistic triptych painting designed and commissioned by Princess Antonia and her academic teachers in 1652, installed in 1673 in the small town church of Holy Trinity at Bad Teinach-Zavelstein in the Black Forest, a personal witness of faith.[1]

Princess Antonia died in 1679, having never married. Her body was buried in the Collegiate Church in Stuttgart; but she directed that her heart should be buried in the wall of Trinity Church in Bad Teinach, behind her painting.[1]

Hebrew scholar

An increased interest in the Hebrew language among Christian scholars was one of the effects of the Reformation in Germany, and royal and noble families included it sometimes even in the curriculum of their daughters' education. In the seventeenth century many German women attained to quite a considerable knowledge of Hebrew. Antonia of Württemberg has become one of the best known. She acquired a remarkable mastery of Hebrew; and according to contemporary evidence was also well versed in rabbinic and Kabbalistic lore.[3]

Esenwein, dean of Urach and later professor at Tübingen, wrote in July 1649 to Johannes Buxtorf at Basel that Antonia, "having been well grounded in the Hebrew language and in reading the Hebrew Bible, desires to learn also the art of reading without vowels," and three years later he wrote to Buxtorf that she had made such progress that she had "with her own hand put vowels to the greatest part of a Hebrew Bible".[3]

Philipp Jacob Spener, another pupil of Buxtorf, during his temporary stay at Heidelberg, was on friendly terms with the princess, and they studied Kabbalah together. Buxtorf himself presented her with a copy of each of his books. There is a manuscript extant in the Royal Library of Stuttgart, entitled Unterschiedlicher Riss zu Sephiroth which is supposed to have been written by Antonia. It contains kabbalistic diagrams, some of which are interpreted in Hebrew and German. Her praise was sung by many a Christian Hebraist; one poem in twenty-four stanzas with her acrostic, in honour of the "celebrated Princess Antonia", has been preserved in Johannes Buxtorf's collection of manuscripts.[3]

The Kabbalistic Lehrtafel at Bad Teinach

The Kabbalistic Lehrtafel ("teaching painting") of Princess Antonia at Bad Teinach stands over six metres tall and five metres wide, dominating the area to the right of the altar in the small church. Planned in 1652 by the princess with a circle of court academic advisors, it was executed in 1659-1663 by Johann Friedrich Gruber, the court painter at Stuttgart, and installed in 1673 at Bad Teinach, where the ducal family used to take holidays in summer, and where Antonia's brother Duke Eberhard had established the church as a private family chapel, built in 1662-1665.[4]

The painting is in the form of a triptych. The two outside panels depict the procession of the soul as the mystical bride of Christ. These open to reveal in two flanking panels a daytime scene of the finding of Moses in the Nile, and a night-time scene of the flight of the Holy Family to Egypt; and in the centre an immensely detailed systema totius mundi - a depiction of a philosophical system of the whole world.[4]

The central panel finds a woman holding in her right hand a flaming heart (charity), with in her left an anchor (faith) and a cross (hope), standing at the threshold of a garden enclosed by a hedge of roses. In the middle of the garden is Jesus, and around him a circle of the fathers of the twelve tribes of Israel.[4]

Beyond them hovers a female figure, in front of a richly decorated temple with an onion dome. Arranged in the composition on and around the temple are nine female figures representing the sephirot, according to their places in the traditional tree of life of the Kabbalah. The tenth of the sephirot, Malchut (kingdom), is represented by the figure of Christ himself. Everywhere in the execution there is more and more intricate detail, symbol upon symbol, meaning upon meaning.[4]

Ancestry

References

- Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg, "Archivale des Monats Archived 2009-11-02 at the Wayback Machine" (in German), March/April 2005

- Stefanie Schäfer-Bossert (2006), The Representation of Women in Religious Art and Imagery: Discontinuities in Female Virtues, pp 142-144, in Gender in transition: discourse and practice in German-speaking Europe, 1750-1830. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06943-8

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Moses Beer (1901–1906). "Antonia, Princess of Würtemberg". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Based on M. Kayserling (1897), A Princess as Hebraist, Jewish Quarterly Review Vol. 9, No. 3 (Apr., 1897), pp. 509-514

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Moses Beer (1901–1906). "Antonia, Princess of Würtemberg". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Based on M. Kayserling (1897), A Princess as Hebraist, Jewish Quarterly Review Vol. 9, No. 3 (Apr., 1897), pp. 509-514 - Eva Johanna Schauer (2006), Jüdische Kabbala und christlicher Glaube. Die Lehrtafel der Prinzessin Antonia zu Württemberg in Bad Teinach (in German) In: Freiburger Rundbrief. Zeitschrift für christlich-jüdische Begegnung 13. 2006, pp. 242–255.

Further reading

- German Wikipedia has an extensive bibliography of works in German. In particular:

- Otto Betz, Isolde Betz (2000): Licht vom unerschaffnen Lichte. Die kabbalistische Lehrtafel der Prinzessin Antonia. 2nd Edition. Metzingen: Sternberg Verlag [Riederich] ISBN 3-87785-022-7. (in German) -- Richly illustrated; but leaves the detail of the allegories in the painting largely unexplored.

- Friedrich Christoph Oetinger (1763): Die Lehrtafel der Prinzessin Antonia. (Reinhard Breymayer and Friedrich Häußermann, eds.). 2 vols. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1977 (Texte zur Geschichte des Pietismus, Abt. 7, Bd. 1, Teil 1. 2). ISBN 3-11-004130-8 (in German) -- Classic 18th-century presentation of the allegorical content of the painting. The second volume gives modern annotations.

External links

- Eva-Johanna Schauer (2006), Jüdische Kabbala und christlicher Glaube: Die Lehrtafel der Prinzessin Antonia zu Württemberg in Bad Teinach (in German)

- Adam McLean (1981), The kabbalistic-alchemical altarpiece in Bad Teinach. From the Hermetic Journal 12, Summer, 1981, pages 21–26.

- Bad Teinach evangelical church community Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. Visiting information (in German)

- Christian Kabbalism, The Lehrtafel of Princess Antonia

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)