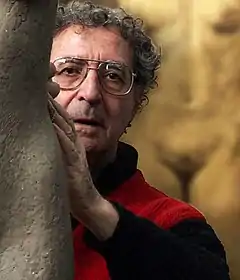

Antonio Pujía

Antonio Pujía (11 June 1929[1][2] – 26 May 2018)[3] was an Argentinian sculptor. Through his artwork he always both honoured women and also denounced the world's horrors of famine and war.

Personal life

Antonio Pujía was born in Polia, a small town in Calabria, southern Italy, on June 11, 1929. In May 1937 he emigrated with his mother and older sister Carmela to Argentina, where his father Vittorio (who had traveled when Antonio was only two years old) was expecting them. Since his early childhood (and because his difficulty with the Spanish language) he began to draw elements of reality that will attract his attention by the novelty meant for. Upon graduation, the teacher guides students in their future education and tells Pujía that he should follow Fine Arts.[4]

He has a son from his first marriage: Vittorio Pujia, a musician who lives in France. In 1960 he joined for love Susana Nicolai (a Psychologist and Ceramist) his lifelong partner, with whom he has two children: Lino Pujía (an Argentinian filmmaker)[5] and Sandro Pujía (an Argentinian photographer).[6]

Education

Pujía began attending the Buenos Aires's numerous studios in 1943, developing an interest in painting and sculpture. One of his early mentors was the realist sculptor Rogelio Yrurtia. He obtained a MFA in Sculpture, from the National College of Fine Arts Ernesto de la Cárcova (1954). He also earned a degree as a Professor of Sculpture from the National School of Fine Arts Prilidiano Pueyrredón (1950) and a bachelor's degree in Fine Arts (Drawing) from the School of Fine Arts Manuel Belgrano (1946).

Artistic life

Colón Theatre: 1956–1970

In 1956 Pujia won a competition to be the head of newly created Scenic Sculpture Workshop Department at the Colón Theatre, continuing working as director until 1970.[7] From this period comes his fascination with music and dance, two of his favorite subjects. Regularly attends the dancers classes and take endless notes on charcoal on paper. Pujía was close to a number of the opera house's ballet company dancers, and he created a bust of Norma Fontenla (on display at the theatre's foyer). He established his own atelier, and left his post at the Colón Theatre in 1970 to teach at his studio, full-time.

Jewelry and Mini Sculptures: 1970–2018

Although he does not considered himself a jeweler, the jewelry of Antonio Pujía were, during the 70s, emblem of what is now called designer jewelry. He is one of the artist's most devoted to jewelry in Argentina, carrying his sculptures to small scale using the bee wax technique. His themes are women, couples, children, dancers. An opening in "Art Gallery" coincided with the birthday of his wife. "I asked her what gift she wanted and she told me a gem" -says the artist. I made a breastplate with several figures moving perfectly articulated and taking back with a hook. At the opening in the gallery, especially women, did nothing more than ask me for the jewel. Because of that, I had a lot of proposals of orders to make rings, etc. So, that was the way I started in the artistic jewelry.[8] Antonio Pujía turns to the privacy of the goldsmith work in small pieces conquered by its lyrics, by the quiet, yet nervous cadence that presided, by the fineness of detail and the sweetness of the effects, the continuation of a lineage familiar to magic, illusion, the brief, poignant, concise poem.[9]

¿Biafra?: 1971

This series of sculptures in reference to the Nigerian Civil War or otherwise known as "Biafra War", displayed a departure in his style, which began to dramatize social and global problems. ¿Biafra? has its sad moment of inspiration in hunger and death that ravage that area of Africa, although it is obvious from the title itself to these scourges re probation anywhere.[10] Pujía said: these works are a reflection of the scourge of hunger, I focused on the Biafran guys, but the meaning was wider... because I think that a scourge of this kind is the most unfair thing that we humans can make, with the hunger of our children who are totally helpless and dependent on us.[11] A casual observation of a photograph of a child in Biafra was triggering the theme of this Pujía´s work. The search for a categorically own image emerged as something long matured, hurt by the painful stimulus. The series of bronze and other materials which the author called ¿Biafra? is among the most valuable of Argentina sculpture of all time.[12]

Love Series: 1968–2018

With clay, plaster, bronze or marble carving, Pujía exalted the love of the couple since the sixties. The human couple is for him "Column of Life" name given to his sculpture of Carrara marble carving of more than two meters. I believe in the forces of love. Perhaps because love is the pendulum opposite of the calamities. If we think of aggression, destruction, death, torture exerted by humans to humans, if we think of all that, the love, the couple are just the opposite. Humans have always sailed at infinity, jumping between these two poles: the repulsion and attraction. The destruction and love. Crime and pregnancy. Love is. Even if it last a day, or last fifty years Love is- says Pujía.[13]

In the Love Series, men and women have, like in reality, front and back, desires of fusion or moments of loneliness. Pujia starts in a bold way, the variety of materials, the precious mobility obtained with simple rotary-bases procedures, neatly assembled surfaces – make of his couples that love each other, a mutable and rich world.[14] The theme of love takes precedence in several respects. Love in the human couple is sublimation in search of integration and unity. The couple is not complemented by binding but in essence is unity, ie eternity. In some of his works man and woman are not embracing each other, or do not face each in its entirety, but the only figure is given by half man, half woman, to give one form as the result: the human being is made, integrated that way. So overcome loneliness, in symbiosis with blood and soul and reaches integrity because it feeds on infinity.[15]

In the sculpture "Man - Woman" (1996), the artist Antonio Pujía has incorporated some Cubist winks in the arrangement of splitting. By mixing these elements, it has continued with the Cubist ideology "show what you know, not just what you see." Hips backwards and heads rotated are the most notorious elements that refer to this artistic ism. In the sculpture "Man - Woman" has been played by the union of two figures, a supposedly female and the other male, which is only recognizable as such by the exhibition of his member. By unifying these two entities into one volumetric construction, the artist wanted to represent a partner concept political present in most of his art exhibitions: gender equality.[16]

Designed medals: 1971–2010

Beginning in 1971, Antonio Pujía has created several artistic medals to commemorate private and national events, as well as to reward renowned people. A medal is, strictly speaking, a small, flat, and round (at times, ovoid) piece of metal that has been sculpted, molded, cast, struck, stamped, or some way marked with an insignia, portrait, or other artistic rendering. A medal may be awarded to a person or organization as a form of recognition for sporting, military, scientific, academic, or various other achievements. An artist who creates medals or medallions is called a "medallist" (UK) or "medalist" (US).

- 1971:Grand Prize SADAIC (Argentina Association of Authors and Composers).

- 1978: TV award of the Argentinian Chamber of Television.

- 1979: SADAIC Awards Medal to authorial right.

- 1980: Plaque commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Colon Theatre.

- 1980: Medal and Trophy for Clarín.

- 1980: Medal commemorating the First Centenary of the Jockey Club of Buenos Aires.

- 1980: Medal to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the founding of Buenos Aires City.

- 1983: Medal to celebrate Argentina´s return to democracy with the inauguration of Raúl Alfonsín.

- 1992: Trophies for Techno Entrepreneurs by the Argentinian Credit Bank.

- 1993: Trophy Award for ARCOR Company.

- 1993: SADAIC homage to Atahualpa Yupanqui.

- 1993: Moon, Grand National Endowment for the Arts Award.

- 1994: Trophy for the opening of the Avenue Theater, and sculpture located in the bearing.

- 1995: Trophy Love Duo by SADAIC.[17]

- 2010: "In union and freedom" Bicentennial Medal of the May Revolution.[18]

His 1975 exhibit at the San Martín Cultural Center was a particular success, and Pujía added his entire warehouse of works to the initial display. He lived in Spain from 1975 to 1976, working in the renowned Escorial Museum.

Among his most successful later series was that of his "Homage to the Woman," which he began in 2004. Suspending his teaching activities, he devoted subsequent years to developing the project.[19]

Academic life

In the early years of study he didn't even dreamed of becoming a teacher. I wanted to learn from my teachers, Fioravanti, Bigatti, Troiano Troiani, and then worked in their studios for a living. Teaching comes in 1949, when I won a prize in the Students and Alumni Association of Fine Arts (MEEBA) and its president called me to give classes. 'Not at all, I did not finish the Pueyrredón' I remember I answered. I resisted a little, and offered me to test a month. Then was born that kind of passion aroused by the teaching, which is a form of learning.[20]

For several decades he taught sculpture in the National College of Fine Arts Ernesto de la Cárcova, in the National School of Fine Arts Prilidiano Pueyrredón and in the School of Fine Arts Manuel Belgrano. He was invited every year to give a lecture at UNA (National University of the Arts), in a cycle of "Talks with Leading Exponents of Visual Arts".[21]

For many years and currently, Pujia dictates Seminars on Modeling in Beeswax, in his studio in Floresta neighborhood. The course focuses on the ancient technique of using beeswax sculpture and the diversity of its use: both, as a raw material to keep the pieces in wax and its application to the famous "lost wax casting" for parts both large and small pieces of jewelry to format.

Awards

- 2010 - Distinction "Italian Roots in Argentina" by Comitatis Degli Italiani All Estero[22]

- 1992 - Illustrious citizen of Buenos Aires

- 1992 - Premio "Recorrido Dorado" S.D.D.R.A

- 1983 - Premio "Palmas Joaquín V. Gonzalez", Gobierno provincia de La Rioja

- 1982 - Cavalieri Ordine al merito della Repubblica italiana

- 1982 - Fundación Konex, Premio destinado a las mejores figuras de las Artes Visuales Argentinas.

- 1981 - Premio Adquisición Gobierno de Santa Fe LVIII Salón Annual de Artes Plásticas. Museo de Bellas Artes, Santa Fe

- 1980 - Premio Revista "Salimos"

- 1974 - Rotary Club de Buenos Aires, Ateneo Rotario, Laurel de Plata

- 1973 - First Prize 50 Aniversario Salón Annual de Santa Fe

- 1972 - First Prize del Salón Nacional de Tucumán

- 1972 - Premio Especial Medalla de Oro Salón IPCLAR, Provincia de Santa Fe.

- 1971 - Premio a la Mejor Muestra del Fondo Nacional de las Artes

- 1970 - Dirección de Turismo Award, Salón annual de Tucumán

- 1966 - Grand Prize in the Primera Bienal de Escultura de la Municipalidad de Quilmes

- 1966 - First Prize Salón de Artes Plásticas de Campana, Provincia de Buenos Aires

- 1964 - Dr. Augusto Palanza Award[23]

- 1960 - Grand Prize of Honor del Salón Nacional

- 1959 - Grand Prize at the Salón Municipal Manuel Belgrano

References

- "Lyra". 1973.

- "Antonio Pujia, Biografía".

- "Muere el escultor Antonio Pujía - LA NACION". La Nación. Archived from the original on 2018-05-28. Retrieved 2018-05-29.

- "Biografía Antonio Pujía". antoniopujia.com (in Spanish). 2004. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- "Lino Pujía". cinenacional.com (in Spanish). 2001. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- "Arte del Mundo - Portal Creativo: Sandro Pujía" [World Art - Creative Portal: Sandro Pujía]. artedelmundo.com.ar (in Spanish). 2012. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- Coppola, Norberto (August 1970). Urtizberea, Raúl (ed.). "Pujia Antonio: Escultor" [Pujia Antonio: Sculptor]. Argentina 17 (in Spanish). Buenos Aires, Argentina (Año 2 - No.17): 74.

- Daverio, Leda (December 30, 2011). "De la cera al metal. Entrevista a Antonio Pujia" [From wax to metal. Interview with Antonio Pujía.]. Hilvanadas en Zig Zag (in Spanish). Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- Magrini, César (October 1980). "Alonso - Pujía - Cañás / Terceto Sinfónico" [Alonso - Pujía - Cañás / Symphonic Trio]. Municipalidad de Quilmes (in Spanish). Buenos Aires, Argentina: 3.

- Galli, Aldo (September 10, 2000). "Pujía: Amores y Dolores" [Pujía: Loves and Pains]. La Nación (in Spanish). Buenos Aires, Argentina. p. 2. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- Berti, Vico (1987). "Antonio Pujía, Escultor: Un Calabrés Universal" [Antonio Pujía, Sculptor: A Universal Calabres]. Arte. Oggi Calabria (in Spanish) (3): 38–39.

- Benarós, León (1974). "Lirismo expresionista de un escultor argentino" [Expressionist lyricism of an Argentine sculptor] (PDF) (in Spanish). Revista Norte. pp. 43–44. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- Braceli, Rodolfo (April 16, 1990). "Este Escultor es una Joya" [This is a gem Sculptor]. Para Tí (in Spanish). Buenos Aires, Argentina: 17.

- Lynch, Marta (September 23, 1968). "Pujia, cuarenta obras únicas" [Pujia forty unique works]. Art Gallery (in Spanish). Buenos Aires, Argentina: 3.

- "Antonio Pujía, una expresión de amor y de ternura en hierro y bronce" [Antonio Pujía, an expression of love and tenderness in iron and bronze]. Información Argentina (in Spanish). Buenos Aires, Argentina (48): 36–37. January 1972.

- Fido. "Antonio Pujía y el movimiento artístico Cubismo" [Antonio Pujía and Cubism art movement] (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad de Palermo. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- "Pujía, Antonio" (in Spanish). Codigo Ciudadano. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- "El Rector de la UBA fue distinguido con la "Medalla del Bicentenario" por el Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires" [The Rector of the UBA was awarded the "Bicentennial Medal" by the Government of the City of Buenos Aires] (in Spanish). UBA University of Buenos Aires. July 30, 2010. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- Antonio Pujía: biography Archived April 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Zacharías, María Paula (September 7, 2013). "Antonio Pujía". mariapaulazacharias.com (in Spanish). Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- "Cursos de Cátedras" [Chairs Courses] (in Spanish). UNA Universidad Nacional de las Artes. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- "Comitato degli Italiani residente all´estero" [Committee of Italians resident abroad]. comites-it.org (in Italian). Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- "Premio Fondo Nacional de la Artes Dr. Augusto Palanza" [National Endowment for the Arts Award, Dr. Augusto Palanza] (in Spanish). Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes. Retrieved December 17, 2015.