Apert syndrome

Apert syndrome is a form of acrocephalosyndactyly, a congenital disorder characterized by malformations of the skull, face, hands and feet. It is classified as a branchial arch syndrome, affecting the first branchial (or pharyngeal) arch, the precursor of the maxilla and mandible. Disturbances in the development of the branchial arches in fetal development create lasting and widespread effects.

| Apert syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acrocephalo-syndactyly type 1[1] |

| |

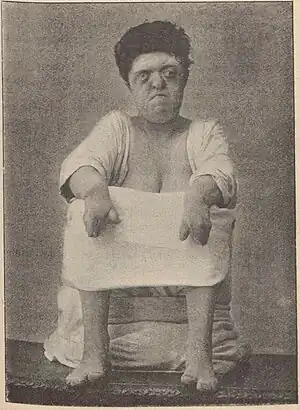

| Woman with Apert syndrome, 1914 | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

| Causes | Genetic mutations; C to G mutation at the position 755 in the FGFR2 gene (two-thirds of cases) |

In 1906, Eugène Apert, a French physician, described nine people sharing similar attributes and characteristics.[2] Linguistically, in the term "acrocephalosyndactyly", acro is Greek for "peak", referring to the "peaked" head that is common in the syndrome; cephalo, also from Greek, is a combining form meaning "head"; syndactyly refers to webbing of fingers and toes.

In embryology, the hands and feet have selective cells that die in a process called selective cell death, or apoptosis, causing separation of the digits. In the case of acrocephalosyndactyly, selective cell death does not occur and skin, and rarely bone, between the fingers and toes fuses.

The cranial bones are affected as well, similar to Crouzon syndrome and Pfeiffer syndrome. Craniosynostosis occurs when the fetal skull and facial bones fuse too soon in utero, disrupting normal bone growth. Fusion of different sutures leads to different patterns of growth on the skull. Examples include: trigonocephaly (fusion of the metopic suture), brachycephaly (fusion of the coronal suture and lambdoid suture bilaterally), dolichocephaly (fusion of the sagittal suture), plagiocephaly (fusion of coronal and lambdoidal sutures unilaterally) and oxycephaly or turricephaly (fusion of coronal and lambdoid sutures).

Findings for the incidence of the syndrome in the population have varied,[3] with estimates as low as 1 birth in 200,000 provided[4] and 160,000 given as an average by older studies.[5][6] A study conducted in 1997, however, by the California Birth Defects Monitoring Program found an incidence rate of 1 in 80,645 out of almost 2.5 million live births.[7] Another study conducted in 2002 by the Craniofacial Center, North Texas Hospital for Children, found a higher incidence of about 1 in 65,000 live births.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Craniosynostosis

The cranial malformations are the most apparent effects of acrocephalosyndactyly. Craniosynostosis occurs, in which the cranial sutures close too soon, though the child's brain is still growing and expanding.[8] Brachycephaly is the common pattern of growth, where the coronal sutures close prematurely, preventing the skull from expanding frontward or backward and causing the brain to expand the skull to the sides and upwards. This results in another common characteristic, a high, prominent forehead with a flat back of the skull. Due to the premature closing of the coronal sutures, increased cranial pressure can develop, leading to mental deficiency. A flat or concave face may develop as a result of deficient growth in the mid-facial bones, leading to a condition known as pseudomandibular prognathism. Other features of acrocephalosyndactyly may include shallow bony orbits and broadly spaced eyes. Low-set ears are also a typical characteristic of branchial arch syndromes.[9][10]

Syndactyly

.JPG.webp)

All acrocephalosyndactyly syndromes show some level of limb anomalies, so it can be hard to tell them apart. However, the typical hand deformities in patients with Apert syndrome distinguish it from the other syndromes.[11] The hands in patients with Apert syndrome always show four common features:[12]

- a short thumb with radial deviation

- complex syndactyly of the index, long and ring finger

- symbrachyphalangism

- simple syndactyly of the fourth webspace

The deformity of the space between the index finger and the thumb may be variable. Based on this first webspace, three different types of hand deformation can be diffentiated:

- Type I: Also called a "spade hand". The most common and least severe type of deformation. The thumb shows radial deviation and clinodactyly but is separated from the index finger. The index, long and ring finger are fused together in the distal interphalangeal joints and form a flat palm. During the embryonic stage, the fusion has no effect on the longitudinal growth of these fingers, so they have a normal length. In the fourth webspace, we always see a simple syndactyly, either complete or incomplete.

- Type II: Also called a "spoon" or "mitten" hand. This is a more serious anomaly since the thumb is fused to the index finger by simple complete or incomplete syndactyly. Only the distal phalanx of the thumb is not joined in the osseous union with the index finger and has a separate nail. Because the fusion of the digits is at the level of the distal interphalangeal joints, a concave palm is formed. Most of the time, we see complete syndactyly of the fourth webspace.

- Type III: Also called the "hoof" or "rosebud" hand. This is the most uncommon but also most severe form of hand deformity in Apert syndrome. There is a solid osseous or cartilaginous fusion of all digits with one long, conjoined nail. The thumb is turned inwards and it is often impossible to tell the fingers apart. Usually proper imaging of the hand is very difficult, due to overlap of bones, but physical examination alone is not enough to measure the severity of deformation.

| Type I ("spade") | Type II ("mitten") | Type III ("rosebud") | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First webspace | Simple syndactyly | Simple syndactyly | Complex syndactyly |

| Middle three fingers | Side-to-side fusion with flat palm | Fusion of fingertops forming a concave palm | Tight fusion of all digits with one conjoined nail |

| Fourth webspace | Simple and incomplete syndactyly | Simple and complete syndactyly | Simple and complete syndactyly |

Dental significance

Common relevant features of acrocephalosyndactyly are a high-arched palate, pseudomandibular prognathism (appearing as mandibular prognathism), a narrow palate and crowding of the teeth.

Other signs

Omphalocele has been described in two patients with Apert syndrome by Herman T.E. et al. (USA, 2010) and by Ercoli G. et al. (Argentina, 2014). An omphalocele is a birth defect in which an intestine or other abdominal organs are outside of the body of an infant because of a hole in the bellybutton area. However, the association between omphalocele and Apert syndrome is not confirmed yet, so additional studies are necessary.[13][14]

Causes

Acrocephalosyndactyly may be an autosomal dominant disorder. Males and females are affected equally; however research is yet to determine an exact cause. Nonetheless, almost all cases are sporadic, signifying fresh mutations or environmental insult to the genome. The offspring of a parent with Apert syndrome has a 50% chance of inheriting the condition. In 1995, A.O.M. Wilkie published a paper showing evidence that acrocephalosyndactyly is caused by a defect on the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 gene, on chromosome 10.[15][16]

Apert syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder; approximately two-thirds of the cases are due to a C to G mutation at the position 755 in the FGFR2 gene, which causes a Ser to Trp change in the protein.[17] This is a male-specific mutation hotspot: in a study of 57 cases, the mutation always occurred on the paternally derived allele.[18] On the basis of the observed birth prevalence of the disease (1 in 70,000), the apparent rate of C to G mutations at this site is about .00005, which is 200- to 800-fold higher than the usual rate for mutations at CG dinucleotides. Moreover, the incidence rises sharply with the age of the father. Goriely et al. (2003) analyzed the allelic distribution of mutations in sperm samples from men of different ages and concluded that the simplest explanation for the data is that the C to G mutation gives the cell an advantage in the male germline.[17]

It is still not very clear why people with Apert syndrome have both craniosynostosis and syndactyly. There has been one study that suggests it has something to do with the expression of three isoforms of FGFR2, the gene with the point mutations that causes the syndrome in 98% of the patients.[19] KGFR, keratinocyte growth factor receptor, is an isoform active in the metaphysis and interphalangeal joints. FGFR1 is an isoform active in the diaphysis. FGFR2-Bek is active in the metaphysis, as well as the diaphysis, but also in the interdigital mesenchyme. The point mutation increases the ligand-dependent activation of FGFR2 and thus of its isoforms. This means that FGFR2 loses its specificity, causing binding of FGFs that normally do not bind to the receptor.[20] Since FGF suppresses apoptosis, the interdigital mesenchyme is maintained. FGF also increases replication and differentiation of osteoblasts, thus early fusion of several sutures of the skull. This may explain why both symptoms are always found in Apert syndrome.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically by the apparent physical characteristics and can be aided by skull X-ray or head CT examination. Molecular genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis.[21]

Treatments

Craniosynostosis

Surgery is needed to prevent the closing of the coronal sutures from damaging brain development. In particular, surgeries for the LeFort III or monobloc midface distraction osteogenesis which detaches the midface or the entire upper face, respectively, from the rest of the skull, are performed in order to reposition them in the correct plane. These surgeries are performed by both plastic and oral and maxillofacial (OMS) surgeons, often in collaboration.

Syndactyly

There is no standard treatment for the hand malformations in Apert due to the differences and severity in clinical manifestations in different patients. Every patient should therefore be individually approached and treated, aiming at an adequate balance between hand functionality and aesthetics. However, some guidelines can be given depending on the severity of the deformities. In general it is initially recommended to release the first and fourth interdigital spaces, thus releasing the border rays.[22] This makes it possible for the child to grasp things by hand, a very important function for the child's development. Later the second and third interdigital spaces have to be released. Because there are three handtypes in Apert, all with their own deformities, they all need a different approach regarding their treatment:[23]

- Type I hand usually needs only the interdigital web space release. First web release is rarely needed but often its deepening is necessary. Thumb clinodactyly correction will be needed.

- In type II hands it is recommended to release the first and fifth rays in the beginning, then the second and the third interdigital web spaces have to be freed. The clinodactyly of the thumb has to be corrected as well. The lengthening of the thumb phalanx may be needed, thus increasing the first web space. In both type I and type II, the recurrent syndactyly of the second web space will occur because of a pseudoepiphysis at the base of the index metacarpal. This should be corrected by later revisions.

- Type III hands are the most challenging to treat because of their complexity. First of all, it is advised to release the first and fourth webspace, thus converting it to type I hand. The treatment of macerations and nail-bed infections should also be done in the beginning. For increasing of the first web space, lengthening of the thumb can be done. It is suggested that in severe cases an amputation of the index finger should be considered. However, before making this decision, it is important to weigh the potential improvement to be achieved against the possible psychological problems of the child later due to the aesthetics of the hand. Later, the second and/or third interdigital web space should be released.

With growing of a child and respectively the hands, secondary revisions are needed to treat the contractures and to improve the aesthetics.

See also

- Other craniosynostosis syndromes:

- Hearing loss with craniofacial syndromes

References

- "Apert syndrome – About the Disease". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- synd/194 at Who Named It?

- Fearon, Jeffrey A. (July 2003). "Treatment of the Hands and Feet in Apert Syndrome: An Evolution in Management". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Dallas, Texas. 112 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000065908.60382.17. ISSN 0032-1052. PMID 12832871. S2CID 8592940.

- Foreman, Phil (2009). Education of Students with an Intellectual Disability: Research and Practice (PB). IAP. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-60752-214-0.

- Carter, Charles H. (1965). Medical aspects of mental retardation. Thomas. p. 358. OCLC 174056103.

- Abe Bert Baker; Lowell H. Baker (1979). "Apert's Syndrome". Clinical Neurology. Medical Dept., Harper & Row. 3: 47. OCLC 11620265.

- Aitken, J. Kenneth (2010). An A-Z of Genetic Factors in Autism: A Handbook for Professionals. Jessica Kingsley. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-84310-976-1.

- "Apert Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- "Apert syndrome". GOSH Hospital site. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- "Apert Syndrome | Boston Children's Hospital". childrenshospital.org. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Kaplan, L C (April 1991). "Clinical assessment and multispecialty management of Apert syndrome". Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 18 (2): 217–25. doi:10.1016/S0094-1298(20)30817-8. ISSN 0094-1298. PMID 2065483.

- Upton, J (April 1991). "Apert Syndrome. Classification and pathologic anatomy of limb anomalies". Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 18 (2): 321–55. doi:10.1016/S0094-1298(20)30826-9. ISSN 0094-1298. PMID 2065493.

- Herman, TE; Siegel, MJ (October 2010). "Apert syndrome with omphalocele". J. Perinatol. 30 (10): 695–697. doi:10.1038/jp.2010.72. PMID 20877364.

- Ercoli, G; Bidondo, MP; Senra, BC; Groisman, B (September 2014). "Apert syndrome with omphalocele: a case report". Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 100 (9): 726–729. doi:10.1002/bdra.23270. PMID 25045033.

- Wilkie, A O; S F Slaney; M Oldridge; M D Poole; G J Ashworth; A D Hockley; R D Hayward; D J David; L J Pulleyn; P Rutland (February 1995). "Apert syndrome results from localized mutations of FGFR2 and is allelic with Crouzon syndrome". Nature Genetics. 9 (2): 165–72. doi:10.1038/ng0295-165. PMID 7719344. S2CID 12423131.

- Conrady, Christopher D.; Patel, Bhupendra C.; Sharma, Sandeep (2022), "Apert Syndrome", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30085535, retrieved 21 September 2022

- Goriely, A.; McVean, GA; Röjmyr, M; Ingemarsson, B; Wilkie, AO (2003). "Evidence for Selective Advantage of Pathogenic FGFR2 Mutations in the Male Germ Line". Science. 301 (5633): 643–6. Bibcode:2003Sci...301..643G. doi:10.1126/science.1085710. PMID 12893942. S2CID 33543066.

- Moloney, DM; Slaney, SF; Oldridge, M; Wall, SA; Sahlin, P; Stenman, G; Wilkie, AO (1996). "Exclusive paternal origin of new mutations in Apert syndrome". Nature Genetics. 13 (1): 48–53. doi:10.1038/ng0596-48. PMID 8673103. S2CID 26465362.

- Britto, J A; J C T Chan; R D Evans; R D Hayward; B M Jones (May 2001). "Differential expression of fibroblast growth factor receptors in human digital development suggests common pathogenesis in complex acrosyndactyly and craniosynostosis". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 107 (6): 1331–1338. doi:10.1097/00006534-200105000-00001. PMID 11335797. S2CID 32124914.

- Hajihosseini MK, Duarte R, Pegrum J, Donjacour A, Lana-Elola E, Rice DP, Sharpe J, Dickson C (February 2009). "Evidence that Fgf10 contributes to the skeletal and visceral defects of an Apert syndrome mouse model". Dev. Dyn. 238 (2): 376–85. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21648. PMID 18773495. S2CID 39997577.

- "Apert syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Zucker, R M (April 1991). "Syndactyly correction of the hand in Apert syndrome". Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 18 (2): 357–64. doi:10.1016/S0094-1298(20)30827-0. ISSN 0094-1298. PMID 1648464.

- Braun, Tara L.; Trost, Jeffrey G.; Pederson, William C. (November 2016). "Syndactyly Release". Seminars in Plastic Surgery. 30 (4): 162–170. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1593478. ISSN 1535-2188. PMC 5115922. PMID 27895538.