Cryptoclidus

Cryptoclidus (/krɪptoʊˈklaɪdəs/ krip-toh-KLY-dəs) is a genus of plesiosaur reptile from the Middle Jurassic period of England, France, and Cuba.[2]

| Cryptoclidus | |

|---|---|

| |

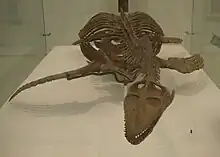

| Cast of a fossil skeleton, University of Tübingen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Cryptoclididae |

| Subfamily: | †Cryptoclidinae |

| Genus: | †Cryptoclidus Seeley, 1892 |

| Type species | |

| †Cryptoclidus eurymerus Phillips, 1871 | |

| Species[1] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Discovery

Cryptoclidus was a plesiosaur whose specimens include adult and juvenile skeletons, and remains which have been found in various degrees of preservation in England, Northern France, Russia, and South America. Its name, meaning "hidden clavicles", refer to its small, practically invisible clavicles buried in its front limb girdle.

The type species was initially described as Plesiosaurus eurymerus by Phillips (1871). The specific name "wide femur" refers to the forelimb, which was mistaken for a hindlimb at the time. Fossils of Cryptoclidus have been found in the Oxford Clay of Cambridgeshire, England. The dubious species Cryptoclidus beaugrandi is known from Kimmeridgian-age deposits in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France.[3] Cryptoclidus vignalensis, which is now considered undiagnostic,[4] hails from the Jagua Formation of western Cuba.[5]

Description

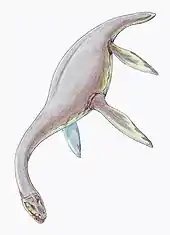

Cryptoclidus was a medium-sized plesiosaur, with the largest individuals measuring up to 4 m (13 ft) long and weighing about 737–756 kg (1,625–1,667 lb).[1][6] The fragile build of the head and teeth preclude any grappling with prey, and suggest a diet of small, soft-bodied animals such as squid and shoaling fish. Cryptoclidus may have used its long, intermeshing teeth to strain small prey from the water, or perhaps sift through sediment for buried animals.[7]

The size and shape of the nares and nasal openings have led Brown and Cruickshank (1994) to argue that they were used to sample seawater for smells and chemical traces.[8]

Classification

The cladogram below follows the topology from Benson et al. (2012) analysis.[9]

References

- Brown, D. S. (1981). "The English Upper Jurassic Plesiosauridea (Reptilia) and a review of the phylogeny and classification of the Plesiosauria". Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History. 35 (4): 253–347.

- Brown, David S., and Arthur RI Cruickshank. The skull of the Callovian plesiosaur Cryptoclidus eurymerus, and the sauropterygian cheek. Archived 2014-03-24 at the Wayback Machine Palaeontology 37.4 (1994): 941.

- Bologne-sur-Mer at Fossilworks.org

- Iturralde-Vinent, M.; Norell, M.A. (1996). "Synopsis of Late Jurassic Marine Reptiles from Cuba" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3164): 1–17. S2CID 56459152.

- De la Torre, R., and A. A. Cuervo. (1939). Dos nuevas especies de ichthyosaurios del Jurisico de Vinales. Universidad de La Habana, Depto. Geol. y Paleont. pp. 1-9.

- Motani, R. (2002). "Swimming speed estimation of extinct marine reptiles: energetic approach revisited". Paleobiology. 28 (2): 251–262. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2002)028<0251:sseoem>2.0.co;2. S2CID 56387158.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 75. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- Brown and Cruickshank, 1994

- Benson, R. B. J.; Evans, M.; Druckenmiller, P. S. (2012). Lalueza-Fox, Carles (ed.). "High Diversity, Low Disparity and Small Body Size in Plesiosaurs (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Triassic–Jurassic Boundary". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e31838. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731838B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031838. PMC 3306369. PMID 22438869.

Further reading

- Z. Gasparini and L. Spaletti. 1993. First Callovian plesiosaurs from the Neuquen Basin, Argentina. Ameghiniana 30(3):245-254

.png.webp)