Sasanian defense lines

The defense lines (or "limes") of the Sasanians were part of their military strategy and tactics. They were networks of fortifications, walls, and/or ditches built opposite the territory of the enemies.[1] These defense lines are known from tradition and archaeological evidence.[2]

| Military of the Sasanian Empire |

|---|

| Armed forces and units |

| Ranks |

| Defense lines |

| Conflicts |

The fortress systems of the Western, Arabian, and Central Asian fronts were of both defensive and offensive functions.[3]

Mesopotamia

The rivers Euphrates, Great Zab, and Little Zab acted as natural defenses for Mesopotamia (Asorestan).[4] Sasanian development of irrigation systems in Mesopotamia further acted as water defense lines, notably the criss-crossing trunk canals in Khuzestan and the northern extension of the Nahrawan Canal, known as the Cut of Khusrau, which made the Sasanian capital Ctesiphon virtually impregnable in late Sasanian period.[5]

In the early period of the Sasanian Empire, a number of buffer states existed between Persia and the Roman Empire, which played a major role in Roman-Persian relations. Both empires gradually absorbed these states, and replaced them by an organized defense system run by the central government and based on a line of fortifications (the limes) and the fortified frontier cities, such as Dara,[6] Nisibis, Amida, Singara, Hatra, Edessa, Bezabde, Circesium, Rhesaina (Theodosiopolis), Sergiopolis (Resafa), Callinicum (Raqqa), Dura-Europos, Zenobia (Halabiye), Sura, Theodosiopolis (Erzurum),[7] Sisauranon, etc.

According to R. N. Frye, the expansion of the Persian defensive system by Shapur II r. 309–379) was probably in imitation of Diocletian's construction of the limes of the Syrian and Mesopotamian frontiers of the Roman Empire over the previous decades.[8] The defense line was in the edge of the cultivated land facing the Syrian Desert.[1]

Along the Euphrates (in Arbayistan), there was a series of heavily fortified cities as a line of defence.[9]

During the early years of Shapur II (r. 309–379), nomadic Arabian tribesmen made incursions into Persia from the south. After his successful campaign in Arabia (325) and having secured the coasts around Persian Gulf, Shapur II established a defensive system in southern Mesopotamia to prevent raids via land.[10] The defensive line, called the Wall of the Arabs (Middle Persian: War ī Tāzīgān, in Arabic: خندق سابور Khandaq Sābūr, literally "Ditch of Shapur", also possibly "Wall of Shapur"),[11][12][13] consisted of a large moat, probably also with an actual wall on the Persian side, with watchtowers and a network of fortifications, at the edge of the Arabian Desert, located between modern-day al-Basrah and the Persian Gulf.[11][10] The defense line ran from Hit to Basra, on the margin of fertile lands west of Euphrates. It included small forts at key spots, acting as outliers for larger fortifications, some of which have been uncovered.[4]

The region and its defense line was apparently governed by a marzban. In the second half of the Sasanian history, the Lakhmid/Nasrid chiefs also became its rulers. They would have protected the area against the Romans and against the Romans' Arab clients, the Ghassanids, sheltering the agricultural lands of Sasanian Mesopotamia from the nomadic Arabs.[11] The Sasanians eventually discontinued the maintenance of this defense line, since they perceived the main threats to the empire lay elsewhere. However, in 633, the empire's ultimate conquerors actually came from this direction.[14]

In the Caucasus

Massive fortification activity was conducted in the Caucasus during the reign of Kavad I (r. 488–496, 498–531) and later his son Khusrow I (r. 531–579), in response to the pressure by people in the north, such as the Alans. Key components of this defensive system were the strategic passes Darial in the Central Caucasus and Derbent just west of the Caspian Sea, the only two practicable crossing of the Caucasus ridge through which the land traffic between the Eurasian Steppe and the Middle East was conducted. A formal system of rulership was also created in the region by Khusrow I, and the fortifications were assigned to local rulers. This is reflected in titles like "Sharvān-shāh" ("King of Shirvan"), "Tabarsarān-shāh", "Alān-shāh/Arrānshāh",[15][16] and "Lāyzān-shāh".

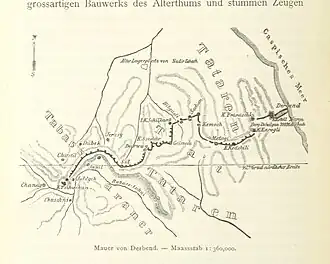

Pass of Derbent

The pass of Derbent (Middle Iranian name is uncertain) was located on a narrow, three-kilometer strip of land in the North Caucasus between the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus mountains. It was in the Sasanian sphere of influence after the victory over the Parthians and the conquest of Caucasian Albania by Shapur I (r. 240/42–270/72). During periods when the Sasanians were distracted by war with the Byzantines or conflicts with the Hephthalites in the east, the northern tribes succeeded in advancing into the Caucasus.[17]

A mud-brick wall (maximum thickness 8 m, maximum height ca. 16 m) near Torpakh-Kala has been attributed to Yazdegerd II (r. 438–457) as the first Sasanian attempt to block the Derbent pass, though it may have been a reconstruction of earlier defenses. It was destroyed in a rebellion in 450.[17]

With a length of 3,650 m on the north side and 3,500 m on the south and featuring seven gates, massive rectangular and round towers and outworks, the Wall of Derbent connected 30 already existing fortifications. Today the northern wall and the main city walls remain, but most of the southern wall is lost. The construction techniques used resemble those of Takht-e Soleiman, also built in the same period.[17] Derbent was also the seat of a Sasanian marzban.[17]

Derbent Wall was the most prominent Sasanian defensive structure in the Caucasus. Later Muslim Arab historians tended to attribute the entire defense line to Khosrow I, and included it among the seven wonders of the world. In the Middle Ages, Alexander the Great was credited with having sealed off the Darband pass against the tribes of Gog and Magog advancing from the north;[17] whence the name "Gate of Alexander" and the "Caspian Gates" for the Derbent pass.

Apzut Kawat (Gilgilchay)

Location: 41.133°N 49.052°E. The second known Sasanian reconstruction of the fortifications in the Caucasus is attributed to the second reign of Kavadh I r. 498–531, who constructed the long fortification walls at Besh Barmak (recorded as Barmaki Wall in Islamic sources), Shabran and Gilgilchay (recorded as Arabic Sur al-Tin in Islamic sources), also called the Apzut Kawat (recorded in Armenian sources, from Middle Persian *Abzūd Kawād, literally "Kavadh increased [in Glory]" or "has prospered"). [16]

The lines were constructed using a combination of mud brick, stone blocks, and baked bricks. The construction was carried out in three phases, extending to the end of the reign of Khusrow I, but was never actually completed. The defensive line is about 60 km in length, from the Caspian Sea to the foot of Mount Babadagh. In 1980, the Ghilghilchay wall was excavated by an expedition of Azeri archaeologists from the Institute of History of Azerbaijan. [18] Not far from the Gilgilchay wall is the Shabran wall, located near Shabran village. [19]

Darial Gorge

Darial Gorge (Middle Persian: ʾlʾnʾn BBA Arrānān dar, Parthian: ʾlʾnnTROA; meaning "Gate of the Alans"),[20] located in the Caucasus, fell into Sasanian hands in 252/253 as the Sasanian Empire conquered and annexed Iberia.[21] It was fortified by both Romans and Persians. The fortification was known as Gate of the Alans, Iberian Gates, and the Caucasian Gates.

_(14764201711).jpg.webp) The Darial Gorge

The Darial Gorge.jpg.webp) Darial Gorge, 1847

Darial Gorge, 1847 Darial Gorge, before 1919

Darial Gorge, before 1919

South-east Caspian

For the defense of the Central Asian border, a different strategy was needed: the maximum concentration of forces in large strongholds, with Marv as the outer bulwark, backed by Nishapur.[4] The defense line was based on a three-tier system that allowed the enemy to penetrate deep into the Sasanian territories and to be channeled into designated kill zones between the tiers of forts. The mobile aswaran cavalry would then carry out counter-attacks from strategically positioned bases, notably Nev-Shapur (Nishabur). Kaveh Farrokh likens the strategy to the Central Asian tactic of Parthian shot—a feigned retreat followed by a counter-attack.[22]

Great Wall of Gorgan

The Great Wall of Gorgan (or simply the Gorgan Wall) was located in north of the Gorgan River in Hyrcania, at a geographic narrowing between the Caspian Sea and the mountains of northeastern Persia. It is widely attributed to Khosrow I, though it may date back to the Parthian period.[2][23] It was on the nomadic route from the northern steppes to the Gorgan Plain and the Persian heartland, probably protecting the empire from the peoples to the north,[24][25] in particular, the Hephtalites.

The defensive line was 195 km (121 mi) long and 6–10 m (20–33 ft) wide,[26] featuring over 30 fortresses spaced at intervals of between 10 and 50 km (6.2 and 31.1 mi). It is described as "amongst the most ambitious and sophisticated frontier walls" ever built in the world,[27] and the most important fortification in Persia.[28] The garrison size for the wall is estimated to be 30,000 strong.[27]

Wall of Tammisha

The Wall of Tammisha (also Tammishe), with a length of around 11 km, was stretched from the Gorgan Bay to the Alborz mountains, in particular, the ruined town of Tammisha at the foot of the mountains. There is another fortified wall 22 km to the west running parallel to the mentioned wall, between modern cities of Bandar-e Gaz and Behshahr.[28]

The Wall of Tammisha is considered to be the second line of defence after the Gorgan Wall.[29]

Other defense lines

- the limes of Sistan[2]

- Khurasan Wall, a defense line west of modern-day Afghanistan[1][30]

- the Gawri Wall, a wall near modern-day Iran-Iraq border, possibly built in the Parthian or Sasanian period[30][31]

Interpretation

Recently, Touraj Daryaee has suggested the defensive walls may have had symbolic, ideological and psychological dimension as well, connecting the practice of enclosing the Iranian (ēr) lands against non-Iranian (anēr) barbarians to the cultural elements and ideas present among Iranians since ancient times, such as the idea of walled paradise gardens.[11]

References

- "BYZANTINE-IRANIAN RELATIONS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- "ARCHITECTURE iii. Sasanian Period – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2012). Sassanian Elite Cavalry AD 224–642. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-78200-848-4.

- Howard-Johnston, James (2012). "The Late Sasanian Army". Late Antiquity: Eastern Perspectives: 87–127.

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (2008). The Sasanian Era. I.B. Tauris. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-84511-690-3.

- Frye (1993), 139

- Fisher, Greg (2011-04-14). Between Empires: Arabs, Romans, and Sasanians in Late Antiquity. ISBN 9780199599271.

- Frye (1993), 139; Levi (1994), 192

- "ARBĀYISTĀN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- Ward, Steven R. (2014). Immortal: A Military History of Iran and Its Armed Forces. Washington: Georgetown University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9781626160651.

- Touraj Daryaee, "If these Walls Could Speak: The Barrier of Alexander, Wall of Darband and Other Defensive Moats", in Borders: Itineraries on the Edges of Iran, ed. S. Pello, Venice, 2016.

- "Šahrestānīhā ī Ērānšah" (PDF). www.sasanika.org.

- "QADESIYA, BATTLE OF – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- Spring, Peter (2015). Great Walls and Linear Barriers. Pen and Sword. p. 198. ISBN 9781473854048.

- Sijpesteijn, Petra; Schubert, Alexander T. (2014). Documents and the History of the Early Islamic World. BRILL. p. 35–37. ISBN 9789004284340.

- "APZUT KAWĀT WALL – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- Kettenhofen, Erich (15 December 1994). "DARBAND – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 22 June 2017. Available in print: Vol. VII, Fasc. 1, pp. 13-19

- Magomedov, Rabadan; Murtazali, Gadjiev (2006). "The Gilgilchay Long Defensive Wall: New Investigations". Ancient East and West. 5 (1, 2): 149. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- "The Caspian Shore Defensive Constructions". UNESCO. 24 October 2001.

- Res Gestae Divi Saporis

- Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge history of Iran, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-521-20092-X, 9780521200929, p. 141

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2012). Sassanian Elite Cavalry AD 224–642. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-848-4.

- Sauer, E, Nokandeh, J, Omrani Rekavadi, H, Wilkinson, T, Abbasi, GA, Schwenninger, J-L, Mahmoudi, M, Parker, D, Fattahi, M, Usher-Wilson, LS, Ershadi, M, Ratcliffe, J & Gale, R 2006, "Linear Barriers of Northern Iran: The Great Wall of Gorgan and the Wall of Tammishe", Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies, vol 44, pp. 121-173.

- Kiani, M. Y. "Gorgan, iv. Archeology". Encyclopaedia Iranica (online edition). New York. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Omrani Rekavandi, H., Sauer, E., Wilkinson, T. & Nokandeh, J. (2008), The enigma of the red snake: revealing one of the world’s greatest frontier walls, Current World Archaeology, No. 27, February/March 2008, pp. 12-22.PDF 5.3 MB.

- "The Enigma of the Red Snake (Archaeology.co.uk)". Archived from the original on March 11, 2009.

- Ball, Warwick (2016). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge. p. 365. ISBN 9781317296355.

- "FORTIFICATIONS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- Barthold, Vasilii Vladimirovich (2014). An Historical Geography of Iran. Princeton University Press. p. 238, footnote 49. ISBN 9781400853229.

- Alibaigi, Sajjad (2019). "The Gawri Wall: a possible Partho-Sasanian structure in the western foothills of the Zagros Mountains". Antiquity. 93 (370). doi:10.15184/aqy.2019.97. ISSN 0003-598X.

- Jarus, Owen (5 November 2019). "Ancient 70-Mile-Long Wall Found in Western Iran. But Who Built It?". livescience.com.

Further reading

- R. N. Frye, “The Sasanian System of Walls for Defense,” Studies in Memory of Gaston Wiet, Jerusalem, 1977.

- Alizadeh, Karim (23 January 2014). "Borderland Projects of Sasanian Empire: Intersection of Domestic and Foreign Policies" (PDF). Journal of Ancient History. 2 (2). doi:10.1515/jah-2014-0015. S2CID 163581755.

- Howard-Johnston, James (2014). "The Sasanian state: the evidence of coinage and military construction". Journal of Ancient History. 2 (2): 144–181. doi:10.1515/jah-2014-0032.