Lesser Antillean macaw

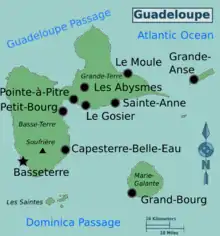

The Lesser Antillean macaw or Guadeloupe macaw (Ara guadeloupensis) is a hypothetical extinct species of macaw that is thought to have been endemic to the Lesser Antillean island region of Guadeloupe. In spite of the absence of conserved specimens, many details about the Lesser Antillean macaw are known from several contemporary accounts, and the bird is the subject of some illustrations. Austin Hobart Clark described the species on the basis of these accounts in 1905. Due to the lack of physical remains, and the possibility that sightings were of macaws from the South American mainland, doubts have been raised about the existence of this species. A phalanx bone from the island of Marie-Galante confirmed the existence of a similar-sized macaw inhabiting the region prior to the arrival of humans and was correlated with the Lesser Antillean macaw in 2015. Later that year, historical sources distinguishing between the red macaws of Guadeloupe and the scarlet macaw (A. macao) of the mainland were identified, further supporting its validity.

| Lesser Antillean macaw | |

|---|---|

| |

| Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre's 1667 illustration showing three Guadeloupe amazons (8) and one Lesser Antillean macaw (7) on a tree at the left | |

Extinct (c. 1760) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Genus: | Ara |

| Species: | †A. guadeloupensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Ara guadeloupensis (Clark, 1905) | |

| |

| Location of the Guadeloupe region | |

According to contemporary descriptions, the body of the Lesser Antillean macaw was red and the wings were red, blue and yellow. The tail feathers were between 38 and 51 cm (15 and 20 in) long. Apart from the smaller size and the all-red coloration of the tail feathers, it resembled the scarlet macaw and may, therefore, have been a close relative of that species. The bird ate fruit – including the poisonous manchineel, was monogamous, nested in trees and laid two eggs once or twice a year. Early writers described it as being abundant in Guadeloupe, but it was becoming rare by 1760, and only survived in uninhabited areas. Disease and hunting by humans are thought to have eradicated it shortly afterward. The Lesser Antillean macaw is one of 13 extinct macaw species that have been proposed to have lived in the Caribbean islands. Many of these species are now considered dubious because only three are known from physical remains, and there are no extant endemic macaws on the islands today.

Taxonomy

The Lesser Antillean macaw is well-documented compared to most other extinct Caribbean macaws since it was mentioned and described by several contemporary writers.[1] Parrots thought to be the Lesser Antillean macaw were first mentioned by the Spanish historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés in 1553, referring to a 1496 account by the Spanish bibliographer Ferdinand Columbus, who mentioned chicken-sized parrots—which the Island Caribs called "Guacamayas"—in Guadeloupe.[2] In 1774, the French naturalist Comte de Buffon stated that the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus had found macaws in Guadeloupe. The French botanist Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre gave the first detailed descriptions in 1654 and 1667 and illustrated the bird and other animals found in Guadeloupe. The French clergyman Jean-Baptiste Labat also described the bird in 1742. Writers such as George Edwards and John Latham also mentioned the presence of red and blue macaws on the islands off America.[3][4][5]

The American zoologist Austin Hobart Clark gave the Lesser Antillean macaw its scientific name, Ara guadeloupensis, in 1905, based on the contemporary accounts, and he also cited a 1765 color plate as possibly depicting this species.[3] He wrote that it was different in several ways from the superficially similar scarlet macaw (A. macao), as well as the green-winged macaw (A. chloropterus) and the Cuban macaw (A. tricolor). Clark suggested the species might also have existed on the islands of Dominica and Martinique, based on accounts of red macaws there as well as on Guadeloupe. In his 1907 book Extinct Birds, the British zoologist Walter Rothschild instead claimed each island had its own species, and that the Lesser Antillean macaw was confined to Guadeloupe.[6] In 1908 Clark reclassified the Dominican macaw as a separate species (A. atwoodi), based on the writings of Thomas Atwood.[7] In 1967, the American ornithologist James Greenway wrote that the macaws reported from Guadeloupe could have been imported to the region from elsewhere by the native population, but this is difficult to prove. Greenway also suggested that the scarlet macaw and the Cuban macaw formed a superspecies with the Lesser Antillean macaw and other hypothetical extinct species suggested for Jamaica and Hispaniola.[2][8] The English paleontologist Julian Hume proposed in 2012 that the similarity between the Lesser Antillean macaw and the scarlet macaw indicates that they were close relatives, and that the Guadeloupe species may have descended from the mainland macaw.[1]

A small parrot ulna found on the Folle Anse archaeological site on Marie-Galante, an island in the Guadeloupe region, was assigned to the Lesser Antillean macaw by the ornithologists Matthew Williams and David Steadman in 2001.[8] In 2008, the ornithologists Storrs Olson and Edgar Maíz López cast doubt upon this identification, and proposed that the bone instead belonged to the extant imperial amazon (Amazona imperialis). The size and robustness of the bone was similar to ulnae of the imperial amazon, and though it was worn, the authors identified what appeared to be a notch, which is also present on ulnae of the genus Amazona, but not in the genus Ara.[9] Subfossil remains from the island of Montserrat have also been suggested to belong to the Lesser Antillean macaw.[10] The species was recognized by Birdlife International and the IUCN Red List until 2013, but was not considered valid thereafter.[11][12]

In 2015, a terminal phalanx bone (ungual claw bone) attributable to the genus Ara from south-western Marie-Galante was described by ecologists Monica Gala and Arnaud Lenoble. It was discovered in the Blanchard Cave during excavations in 2013–2014, in a fossil-bearing deposit dating to the late Pleistocene epoch. The deposit was radiocarbon dated to about 10,690 years ago; the earliest evidence of human settlement in the area has been dated to 5,300 years ago. This confirmed that the Guadeloupe region once had an endemic macaw which could not have been brought there by humans. All other macaw bones from the Lesser Antillean islands have been recovered from archaeological sites, and could therefore have been the remains of birds brought there by Amerindians. The size of the phalanx bone matched what was described for the Lesser Antillean macaw by contemporary writers, and the authors therefore correlated the two. They conceded that this connection could only be tentative, as there were no remains of the Lesser Antillean macaw to compare with.[13]

Later in 2015, Lenoble reviewed overlooked historical Spanish and French sources, finding references to mainly red macaws consistent with the Lesser Antillean macaw. The writings of the French missionary Raymond Breton (on Guadeloupe from 1635 to 1654) were especially illuminating, as they showed that both he and the native Island Caribs clearly distinguished between the red macaws of Guadeloupe and the scarlet macaws from the mainland, which supports the idea that the Lesser Antillean macaw represents an independent species. As the Lesser Antillean Carib language had different words reserved for men and women, Breton gave the name of the bird as Kínoulou (♂) and Caarou (♀). Lenoble furthermore concluded that the supposed violet macaw (named Anodorhynchus purpurascens based on accounts of blue parrots from Guadeloupe) was based on misidentified references to the also-extinct Guadeloupe amazon (Amazona violacea), and therefore never existed.[14][15]

As many as 13 now-extinct species of macaw have variously been suggested to have lived on the Caribbean islands, but many of these were based on old descriptions or drawings and only represent hypothetical species.[16] In addition to the Lesser Antillean macaw, only two endemic Caribbean macaw species are known from physical remains; the Cuban macaw is known from 19 museum skins and subfossils, and the Saint Croix macaw (A. autochthones) is known only from subfossils.[9][13] Macaws are known to have been transported between the Caribbean islands and from mainland South America to the Caribbean both in historic times by Europeans and native peoples, and in prehistoric times by Paleoamericans. Parrots were important in the culture of native Caribbeans, and were among the gifts offered to Christopher Columbus when he reached the Bahamas in 1492. Historical records of macaws on these islands, therefore, may not have represented distinct, endemic species; it is also possible that these macaws were escaped or feral birds that had been transported to the islands from elsewhere.[9] All the endemic Caribbean macaws were likely driven to extinction by humans in historic and prehistoric times.[8] The identity and distribution of indigenous macaws in the Caribbean is only likely to be further resolved through paleontological discoveries and examination of contemporary reports and artwork.[10][17]

Description

The Lesser Antillean macaw was described as having similar coloration to the scarlet macaw, but with shorter tail feathers between 38 and 51 cm (15 and 20 in) long.[18] In contrast, the tail feathers of the scarlet macaw are 61 cm (2 ft) long and have blue tips, and the outer feathers are almost entirely blue. In spite of the tail feathers being shorter, it is not certain whether the Lesser Antillean macaw was smaller than the scarlet macaw overall, as the relative proportions of body parts vary between macaw species.[3] The tail feathers were longer than those of the Cuban macaw, which were 30 cm (12 in) long.[8] The morphology of the fossil phalanx bone from Marie-Galante was most similar to the second or third ungual of the scarlet macaw, though the bone is slightly smaller at 15.3 mm (0.60 in) compared to 15–17 mm (0.59–0.67 in).[13]

Du Tertre described the Lesser Antillean macaw as follows in 1654:

The Macaw is the largest of all the parrot tribe; for although the parrots of Guadeloupe are larger than all other parrots, both of the islands and of the main land, the Macaws are a third larger than they... The head, neck, underparts, and back are flame color. The wings are a mixture of yellow, azure, and scarlet. The tail is wholly red, and a foot and a half long.[3]

Though Clark converted Du Tertre's tail measurement to 18 in (45.7 cm), Lenoble pointed out that a 17th-century French foot unit was slightly larger than the English equivalent, and the measurement should rather be converted to 19.3 in (49 cm), indicating a smaller size difference between the Lesser Antillean macaw and the scarlet macaw.[14]

In 1742, Labat described the macaw in much the same way as Du Tertre, while adding several details:

It is the size of a full grown fowl. The feathers of the head, neck, back and underparts are flame color; the wings are of a mixture of blue, yellow and red; the tail, which is from fifteen to twenty inches in length is wholly red. The head and the beak are very large, and it walks gravely; it talks very well, if it is taught when young; its voice is strong and distinct; it is amiable and kind, and allows itself to be caressed...[3]

Both authors wrote that the macaws were the largest parrots of Guadeloupe, and stressed that the parrots of each Caribbean island were distinct, and could be differentiated both based on their morphology and their vocalizations.[3] According to Hume, this means that the birds described could not simply have been escaped South American macaws. Furthermore, the docile and amiable nature described by Du Tertre and Labat does not match the behavior of South American macaws.[1]

Breton's mid-1600s accounts of the macaw confirmed it as distinct from mainland scarlet macaws:

Macaws are larger than parrots, with a very beautiful red plumage mixed with purple in the tail and wings... Macaws found on islands are called Kínoulou, f. Caarou. Coyáli is found on the continent, and is redder and more elegant than the island variety.[14]

Apart from Du Tertre's crude 1667 drawing and Labat's 1722 derivative, a few contemporary paintings depict red macaws that may be the Lesser Antillean macaw. A color plate accompanying a 1765 volume of Buffon's encyclopaedia Histoire Naturelle (no. 12 in Planches Enluminées, entitled L'Ara Rouge) shows a red macaw with entirely red tail feathers and more red on the tertial and scapular feathers of the wing than are present on the scarlet macaw.[3][10][19] Copies of the plate differ in the nuances used, but are identical in pattern. The painting suggests that a specimen may have been present in Europe at the time. The Swedish zoologist Carl Linnaeus cited the plate in his 1766 description of the scarlet macaw, but his description does not match the bird shown. A 1626 painting by the Dutch artist Roelant Savery, which also includes a dodo, shows a red macaw that agrees with the descriptions of the Lesser Antillean macaw. A second macaw in the painting may be the hypothetical extinct Martinique macaw (A. martinicus), but though many parrots were imported into Europe at the time from all over the world, it is impossible to determine the accuracy of such paintings today.[1][2]

Behavior and ecology

.jpg.webp)

Du Tertre gave a detailed account of the behavior of the Lesser Antillean macaw in 1654:

This bird lives on berries, and on the fruit of certain trees, but principally on the apples of the manchioneel (!), which is a powerful and caustic poison to other animals. It is the prettiest sight in the world to see ten or a dozen Macaws in a green tree. Their voice is loud and piercing, and they always cry when flying. If one imitates their cry, they stop short. They have a grave and dignified demeanor, and so far from being alarmed by many shots fired under a tree where they are perched, they gaze at their companions who fall dead to the ground without being disturbed at all, so that one may fire five or six times into the same tree without their appearing to be frightened.[3]

In a 1667 work, Du Tertre gave a similar account, and added that the macaw only ate the poisonous manchineel (Hippomane mancinella) fruits in times of necessity. He also described the monogamous reproductive behavior of the bird:

The male and the female are inseparable companions and it is rare that one is seen singly. When they wish to breed (which they do once or twice a year) they make a hole with their beaks in the stump of a large tree, and construct a nest with feathers from their own bodies. They lay two eggs, the size of those of a partridge (Perdix cinerea). The others of the parrot kind make their nests in the same way, but lay green eggs... The Macaws are much larger than the large parrots of Guadeloupe or Grenada, and live longer than a man; but they are almost all subject to a falling sickness.[3]

The twice-yearly breeding mentioned by Du Tertre may have actually been staggered breeding, which is practiced by some tropical birds.[1]

Though Clark suggested that the Lesser Antillean macaw also occurred on Dominica and Martinique, there is no evidence for this. Instead, it probably existed on other islands close to Guadeloupe.[8] The fossil phalanx bone from Marie-Galante was deposited in a time when that island and the rest of the Guadeloupe archipelago were closer together than they are today due to lower sea-levels. The areas were separated by three channels, the largest of which was 6 kilometres (3.7 miles) wide. This would not have been a hindrance to flying animals, and the macaws of the Guadeloupe islands would probably have been a single population during the Pleistocene.[13]

Extinction

In 1534, German historian Johann Huttich wrote that the forests of Guadeloupe were full of red macaws, which were apparently as abundant as grasshoppers, and the native people of the region cooked the macaw's flesh together with that of humans and of other birds.[20] In 1654, Du Tertre stated that the flesh was tough to eat and that some considered it unpalatable and even poisonous. He wrote that he and the other inhabitants often consumed it and that he experienced no ill-effects from it. He also stated that the native people wore the feathers decoratively on their heads and as mustaches through the septum of the nose. He described how the bird was hunted by the native population:

The natives make use of a stratagem to take them alive; they watch for a chance to find them on the ground, eating the fruit which has fallen from the trees, when they approach quietly under cover of the trees, then all at once run forward, clapping their hands and filling the air with cries capable not only of astounding the birds, but of terrifying the boldest. Then the poor birds, surprised and distracted, as if struck with thunderbolt, lose the use of their wings, and, making a virtue of necessity, throw themselves on their backs and assume the defensive with the weapons nature has given them – their beaks and claws – with which they defend themselves so bravely that not one of the natives dares to put his hand on them. One of the natives brings a big stick which he lays across the belly of the bird, who seizes it with beak and claws; but while he is occupied in biting it, the native ties him so adroitly to the stick that he can do with him anything he wishes...[3]

Du Tertre wrote that the macaws were prone to sickness, and an outbreak of a disease, along with hunting, may have contributed to its demise.[8] In 1760, the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson quoted a letter by French writer M. de la Borde, which stated that macaws had become very rare in the Antillean islands because they were hunted for food. By then they could only be found in areas not frequented by humans and were probably extinct soon afterward. Parrots are often among the first species to be exterminated from a given locality, especially islands.[3]

References

- Hume, J. P.; Walters, M. (2012). Extinct Birds. A & C Black. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-1-4081-5725-1.

- Greenway, J. C. (1967). Extinct and Vanishing Birds of the World. New York: American Committee for International Wild Life Protection. pp. 315–318. ISBN 978-0-486-21869-4.

- Clark, A. H. (1905). "The Lesser Antillean Macaws". The Auk. 22 (3): 266–273. doi:10.2307/4070159. JSTOR 4070159.

- Du Tertre, J. B. (1667). Histoire Générale des Antilles Habitées par les François (in French). Paris: T. Lolly. pp. 247–250.

- Labat, J. B. (1742). Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l'Amerique (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: Rue Jacques, Chez Guillaume Cavelier pere, libraire, au Lys d'or. pp. 211–221.

- Rothschild, W. (1907). Extinct Birds. London: Hutchinson & Co. p. 54.

- Clark, August Hobart (July 1908). "The Macaw of Dominica". The Auk. 25 (3): 309–311. doi:10.2307/4070527. JSTOR 4070527.

- Williams, M. I.; Steadman, D. W. (2001). "The historic and prehistoric distribution of parrots (Psittacidae) in the West Indies". In Woods, C. A.; Sergile, F.E. (eds.). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 175–189. ISBN 978-0-8493-2001-9.

- Olson, S. L.; Maíz López, E. J. (2008). "New evidence of Ara autochthones from an archeological site in Puerto Rico: a valid species of West Indian macaw of unknown geographical origin (Aves: Psittacidae)" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 44 (2): 215–222. doi:10.18475/cjos.v44i2.a9. S2CID 54593515.

- Wiley, J. W.; Kirwan, G. M. (2013). "The extinct macaws of the West Indies, with special reference to Cuban Macaw Ara tricolor" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 133: 125–156.

- Birdlife International (2016). "Ara guadeloupensis". birdlife.org. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- IUCN Red List (2013). "Ara guadeloupensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Gala, M.; Lenoble, A. (2015). "Evidence of the former existence of an endemic macaw in Guadeloupe, Lesser Antilles". Journal of Ornithology. 156 (4): 1061. doi:10.1007/s10336-015-1221-6. S2CID 18597644.

- Lenoble, A. (2015). "The Violet Macaw (Anodorhynchus purpurascens Rothschild, 1905) did not exist". Journal of Caribbean Ornithology. 28: 17–21.

- Breton, R. (1978). Relations de l'île de la Guadeloupe. Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe: Société d’Histoire de la Guadeloupe. p. 34. ISBN 978-2-900339-13-8.

- Turvey, S. T. (2010). "A new historical record of macaws on Jamaica". Archives of Natural History. 37 (2): 348–351. doi:10.3366/anh.2010.0016.

- Olson, S. L.; Suárez, W. (2008). "A fossil cranium of the Cuban Macaw Ara tricolor (Aves: Psittacidae) from Villa Clara Province, Cuba". Caribbean Journal of Science. 3. 44 (3): 287–290. doi:10.18475/cjos.v44i3.a3. S2CID 87386694.

- Salvadori, T. (1906). "Notes on the parrots (Part V.)". Ibis. 48 (3): 451–465. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1906.tb07813.x.

- Daubenton, E. L. (1765). Planches Enluminées d'Histoire Naturelle (in French). Vol. 1. Paris. p. 12. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.51460.

- Clark, A. H. (1934). "Note on the Guadeloupe Macaw (Ara guadeloupensis)". The Auk. 51 (3): 377. doi:10.2307/4077680. JSTOR 4077680.

External links

Media related to Ara guadeloupensis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ara guadeloupensis at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Ara guadeloupensis at Wikispecies

Data related to Ara guadeloupensis at Wikispecies