Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung

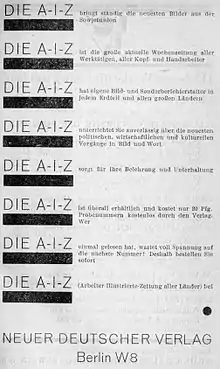

Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung or AIZ (in English, The Workers Pictorial Newspaper) was a German illustrated magazine published between 1924 and March 1933 in Berlin, and afterward in Prague and finally Paris until 1938. Anti-Fascism and pro-Communism in stance, it was published by Willi Münzenberg and is best remembered for the propagandistic photomontages of John Heartfield.

History of the AIZ

The history of the AIZ began with a famine in the Soviet Union and Lenin's appeal of August 2, 1921, to the working class for assistance. As a support organization for this campaign, Workers International Relief (Internationale Arbeiter-Hilfe (IAH)) was formed, based in Berlin and led by William (Willi) Münzenberg.[1] In the autumn of 1921 a monthly German magazine was created, Sowjet Russland im Bild (Soviet Russia in Pictures), with reports about the recently created Russian Soviet state, its achievements and problems, and about the IAH. In 1922 the first reports on the German proletariat appeared in its pages. At this time the monthly circulated about 10,000 copies. The paper grew rapidly during the 1920s as it expanded coverage and attracted prominent contributors like the artists George Grosz and Käthe Kollwitz, and playwrights Maxim Gorki and George Bernard Shaw.

On November 30, 1924, the renamed AIZ appeared with a new format. In 1927 it began publishing on a biweekly schedule, and in 1928 it became a weekly.[2] It became the most widely read socialist pictorial newspaper in Germany. Circulation increased from 250,000 in 1927[3] to 350,000 in 1930.[4] The magazine covered current events and published fiction and poetry, with such contributors as Anna Seghers, Erich Kästner and Kurt Tucholsky. Unlike other labor periodicals it also focused on women's issues and gender relations.[5] Münzenberg wanted the AIZ to connect the Communist Party of Germany to a broad educated readership. In November 1926 AIZ began publishing on a weekly schedule. According to a survey AIZ conducted in 1929, "42 percent of its readers were skilled workers, 33 percent unskilled workers, 10 percent white-collar workers, 5 percent youths, 3.5 percent housewives, 3 percent self-employed, 2 percent independent, and 1 percent civil servants."[6]

The photojournalism, often striking, was predominantly worker photography ("Arbeiterphotographen"), submitted by amateur photographers. Beginning in Hamburg in 1926, Münzenberg established what eventually became a network of Worker Photographer groups across Germany and the Soviet Union.[7] In 1930 began the magazine's association with John Heartfield, whose photomontages savagely attacking both National Socialism and Weimar capitalism became a regular feature.

The last issue published in Berlin was dated March 5, 1933; after the seizure of power by Hitler the AIZ went into exile in Prague.[8] In Prague, AIZ's circulation fell to 12,000, and attempts to smuggle the magazine into Germany failed.[8] Continuing under editor-in-chief Franz Carl Weiskopf, the magazine was renamed Die Volks Illlustriete in 1936. When the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, the publication was moved to Paris in 1938, where it published at least 4 issues before its demise.[9]

Legacy and AIZ in museums

An East German illustrated magazine entitled Neue Berliner Illustrierte was designed based on AIZ.[10]

In 2011 Museo Reina Sofía organized an exhibition in Madrid, A Hard, Merciless Light. The Worker-Photography Movement, 1926-1939, which presented material about amateur social photography. The exhibition included many numbers of the AIZ, as well as the work of amateur worker photographers and other workers' magazines and newspapers in circulation between 1926 and 1939 in Europe, the Soviet Union, and the United States.[11]

Notes

- Scammell 2005.

- McMeekin 2003, p. 350.

- Kreinik 2008, p. 187.

- Weitz 2007, p. 211.

- On women in the AIZ see Hans Sonntag: "Die Proletarierin zwischen Fabrikarbeit, „zweiter Schicht“ und „Sex-Appeal“. Ausgewählte Aspekte zur Frauenfrage in der „Arbeiter-Illustrierten Zeitung“ 1926/27 bis 1933", in: Jahrbuch für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, No. III/2009.

- Lavin & Höch 1993, p. 55.

- Heller & Pomeroy 1997, p. 63.

- Heller & Pomeroy 1997, p. 64.

- Heartfield 1977, p. 128.

- Isabella de Keghel (2010). "Western in Style, Socialist in Content? Visual Representations of GDR Consumer Culture in the Neue Berliner Illustrierte (1953–64)" (PDF). In Sari Autio-Sarasmo; Brendan Humphreys (eds.). Winter kept us warm: Cold war interactions reconsidered. Helsinki: Kikimora Publications. pp. 76–106. ISBN 978-952-10-6564-4.

- Palacios 2011.

References

- Heller, S., & Pomeroy, K. (1997). Design literacy: Understanding graphic design. New York: Allworth Press. ISBN 1-880559-76-5

- Lavin, M., & Höch, H. (1993). Cut with the kitchen knife: The Weimar photomontages of Hannah Höch. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04766-5

- Heartfield, J. (1977). "Photomontages of the Nazi Period. New York: Universe Press. ISBN 0-87663-281-9

- Kreinik, Juliana D. (2008). The Canvas and the Camera in Weimar Germany: A New Objectivity in Painting and Photography of the 1920s. Thesis (Ph.D.)—New York University, Institute of Fine Arts, 2008.

- McMeekin, Sean. (2003). The red millionaire: a political biography of Willi Münzenberg, Moscow's secret propaganda tsar in the West, 1917-1940. New Haven, Conn., London: Yale University Press. ISBN

0-300098-47-2

- Palacios, D. (2011). Del rojo al tono: Fotografía obrera en MNCARS. Revista Mamajuana Digital.

- Scammell, Michael (2005). "The Mystery of Willi Münzenberg". The New York Review of Books. November 3, 2005. pp. 32–35.

- Sonntag, Hans (2009). "Die Proletarierin zwischen Fabrikarbeit, „zweiter Schicht“ und „Sex-Appeal“. Ausgewählte Aspekte zur Frauenfrage in der „Arbeiter-Illustrierten Zeitung“ 1926/27 bis 1933". Jahrbuch für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, No. III/2009.

- Weitz, Eric D. (2007). Weimar Germany: promise and tragedy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691016955