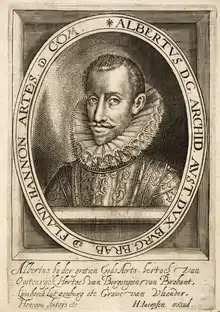

Albert VII, Archduke of Austria

Albert VII (German: Albrecht VII; 13 November 1559 – 13 July 1621) was the ruling Archduke of Austria for a few months in 1619 and, jointly with his wife, Isabella Clara Eugenia, sovereign of the Habsburg Netherlands between 1598 and 1621. Prior to this, he had been a cardinal, Archbishop of Toledo, viceroy of Portugal and Governor General of the Habsburg Netherlands. He succeeded his brother Matthias as reigning archduke of Lower and Upper Austria, but abdicated in favor of Ferdinand II the same year, making it the shortest (and often ignored) reign in Austrian history.

| Albert (VII) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sovereign of the Netherlands Duke of Lothier, Brabant, Limburg, Luxembourg, and Guelders Margrave of Namur Count Palatine of Burgundy Count of Flanders, Artois, and Hainaut | |

| Reign | 6 May 1598 – 13 July 1621[1] |

| Predecessor | Philip II |

| Successor | Philip IV |

| Co-monarch | Isabella Clara Eugenia |

| Archduke of Lower and Upper Austria | |

| Reign | 20 March – 9 October 1619 |

| Predecessor | Matthias |

| Successor | Ferdinand II |

| Viceroy of Portugal | |

| Reign | 11 February 1583 – 5 July 1593 |

| Predecessor | Duke of Alba |

| Successor | 1st Regency Council |

| Monarch | Philip I of Portugal |

| Born | 13 November 1559 Wiener Neustadt |

| Died | 13 July 1621 (aged 61) Brussels |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| House | Habsburg |

| Father | Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Mother | Maria of Spain |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature |  |

Early life

Archduke Albert was the fifth son of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II and Maria of Spain, daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Isabella of Portugal. He was sent to the Spanish Court at the age of eleven, where his uncle, King Philip II, looked after his education, where he was apparently quite intelligent. Initially he was meant to pursue an ecclesiastical career. On 3 March 1577 he was appointed cardinal by Pope Gregory XIII, with a dispensation because of his age of eighteen, and was given Santa Croce in Gerusalemme as his titular church.[2] Philip II planned to make Albert archbishop of Toledo as soon as possible, but the incumbent, Gaspar de Quiroga y Sandoval, lived much longer than expected; he died on 12 November 1594. In the meantime Albert only took lower orders. He was never ordained priest or bishop, and thus he resigned the See of Toledo in 1598.[3] He resigned the cardinalate in 1598.[4] His clerical upbringing did however have a lasting influence on his lifestyle.[5]

After the dynastic union with Portugal, Albert became the first viceroy of the kingdom and its overseas empire in 1583. At the same time he was appointed Papal Legate and Grand Inquisitor for Portugal.[6] As viceroy of Portugal he took part in the organization of the Great Armada of 1588 and beat off an English counter-attack on Lisbon in 1589.[7] In 1593 Philip II recalled him to Madrid, where he would take a leading role in the government of the Spanish Monarchy.[8] Two years later, the rebellious Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone and Hugh Roe O'Donnell offered Albert the Irish crown in the hope of obtaining Spanish support for their cause.[9]

Governor General of the Habsburg Netherlands

After the death of Archduke Ernest of Austria in 1595, Albert was sent to Brussels to succeed his elder brother as Governor General of the Habsburg Netherlands. He made his entry in Brussels on 11 February 1596. His first priority was restoring Spain's military position in the Low Countries. Spain was facing the combined forces of the Dutch Republic, England and France and had known nothing but defeats since 1590. During his first campaign season, Albert surprised his enemies by capturing Calais and nearby Ardres from the French and Hulst from the Dutch. These successes were however offset by the third bankruptcy of the Spanish crown later that year. As a consequence, 1597 was marked by a series of military disasters. Stadholder Maurice of Orange captured the last Spanish strongholds that remained north of the great rivers, as well as the strategic town of Rheinberg in the Electorate of Cologne. Between 13 May and 25 September 1597, the Spanish, who had sent a large army in March, had captured the city of Amiens easily in a ruse. Finally the Spanish Army of Flanders lost Amiens in September the same year to Henry IV of France despite desperate efforts to relieve the place by Albert and Ernst von Mansfeld. With no more money to pay the troops, Albert was also facing a series of mutinies.

.JPG.webp)

While pursuing the war as well as he could, Albert made overtures for peace with Spain's enemies, but only the French King was disposed to enter official negotiations. Under the mediation of the papal legate Cardinal Alessandro de'Medici — the future Pope Leo XI — Spain and France concluded the Peace of Vervins on 2 May 1598. Spain gave up its conquests, thereby restoring the situation of Cateau Cambrésis. France tacitly accepted the Spanish occupation of the prince-archbishopric of Cambray and pulled out of the war, but maintained the financial support for the Dutch Republic. Only a few days after the treaty, on 6 May 1598, Philip II announced his decision to marry his eldest daughter, Isabella Clara Eugenia, to Albert and to cede them the sovereignty over the Habsburg Netherlands. The Act of Cession did however stipulate that if the couple would not have children, the Netherlands would return to Spain. It also contained a number of secret clauses that assured a permanent presence of the Spanish Army of Flanders. After obtaining the pope's permission, Albert formally resigned from the College of Cardinals on 13 July 1598 and left for Spain on 14 September, unaware that Philip II had died the night before. Pope Clement VIII celebrated the union by procuration on 15 November at Ferrara, while the actual marriage took place in Valencia on 18 April 1599.

He was 39 and his bride 33; they had three children who all died in infancy.

War years

The first half of the reign of Albert and Isabella was dominated by war. After overtures to the United Provinces and to Queen Elizabeth I of England proved unsuccessful, the Habsburg policy in the Low Countries aimed at regaining the military initiative and isolating the Dutch Republic. The strategy was to force its opponents to the conference table and negotiate from a position of strength. Even if Madrid and Brussels tended to agree on these options, Albert took a far more flexible stance than his brother-in-law, King Philip III of Spain. Albert had first-hand knowledge of the devastation wrought by the Dutch Revolt, and he had come to the conclusion that it would be virtually impossible to reconquer the northern provinces. Quite logically, Philip III and his councillors felt more concern for Spain's reputation and for the impact that a compromise with the Dutch Republic might have on Habsburg positions as a whole. Spain provided the means to continue the war. Albert took the decisions on the ground and tended to ignore Madrid's instructions. Under the circumstances, the division of responsibilities repeatedly led to tensions.

Albert's reputation as a military commander suffered badly when he was defeated by the Dutch stadtholder Maurice of Orange in the battle of Nieuwpoort on 2 July 1600. His inability to conclude the lengthy siege of Ostend (1601–1604), resulted in his withdrawal from the tactical command of the Spanish Army of Flanders. From then on military operations were led by the Genoese Ambrogio Spínola. Even though he could not prevent the almost simultaneous capture of Sluis, Spínola forced Ostend to surrender on 22 September 1604. He seized the initiative during the next campaigns, bringing the war north of the great rivers for the first time since 1594.

Meanwhile, the accession of James VI of Scotland as James I in England had paved the way for a separate peace with England. On 24 July 1604 England, Spain and the Archducal Netherlands signed the Treaty of London. The return to peace was severely hampered by differences over religion. Events such as the Gunpowder Plot caused a lot of diplomatic tension between London and Brussels. Yet on the whole relations between the two courts tended to be cordial.

Spínola's campaigns and the threat of diplomatic isolation induced the Dutch Republic to accept a ceasefire in April 1607. The subsequent negotiations between the warring parties failed to produce a peace treaty. They did lead however to conclusion of the Twelve Years' Truce in Antwerp on 9 April 1609. Under the terms of the Truce, the United Provinces were to be regarded as a sovereign power for the duration of the truce. Albert had conceded this point against the will of Madrid and it took him a lot of effort to persuade Philip III to ratify the agreement. When Philip's ratification finally arrived, Albert's quest for the restoration of peace in the Low Countries had finally paid off.

Years of peace

_-_Albert_VII%252C_Archduke_of_Austria_-_Prado_001.jpg.webp)

The years of the Truce gave the Habsburg Netherlands a much needed breathing-space. The fields could again be worked in safety. The archducal regime encouraged the reclaiming of land that had been inundated in the course of the hostilities and sponsored the impoldering of the Moeren, a marshy area that is presently astride the Belgian–French border. The recovery of agriculture led in turn to a modest increase of the population after decades of demographic losses. Industry and in particular the luxury trades likewise underwent a recovery. International trade was however hampered by the closure of the river Scheldt. The archducal regime had plans to bypass the blockade with a system of canals linking Ostend via Bruges to the Scheldt in Ghent and joining the Meuse to the Rhine between Venlo and Rheinberg. In order to combat urban poverty, the government supported the creation of a network of Monti di Pietà based on the Italian model.

Meanwhile, the archducal regime ensured the triumph of the Catholic Reformation in the Habsburg Netherlands. Most Protestants had by that stage left the Southern Netherlands. After one last execution in 1597, those that remained were no longer actively persecuted. Under the terms of legislation passed in 1609, their presence was tolerated, provided they did not worship in public. Engaging in religious debates was also forbidden by law. The resolutions of the Third Provincial Council of Mechlin of 1607 were likewise given official sanction. Through such measures and by the appointment of a generation of able and committed bishops, Albert and Isabella laid the foundation of the Catholic confessionalisation of the population. The same period saw important waves of witch-hunts.

In the process of recatholicisation, new and reformed religious orders enjoyed the particular support of Albert and Isabella. Even though the Archduke had certain reservations about the order, the Jesuits received the largest cash grants, allowing them to complete their ambitious building programmes in Brussels and Antwerp. Other champions of the Catholic Reformation, such as the Capuchins, were also given considerable sums. The foundation of the first convents of Discalced Carmelites in the Southern Netherlands depended wholly on the personal initiative of the archducal couple and bore witness to the Spanish orientation of their spirituality.

The reign of Albert and Isabella Clara Eugenia saw a strengthening of princely power in the Habsburg Netherlands. The States General of the loyal provinces were only summoned once in 1600. Thereafter the government preferred to deal directly with the provinces. The years of the Truce allowed the archducal regime to promulgate legislation on a whole range of matters. The so-called Eternal Edict of 1611, for instance, reformed the judicial system and ushered in the transition from customary to written law. Other measures dealt with monetary matters, the nobility, duels, gambling, etc.

Driven by strategic as well as religious motives, Albert intervened in 1614 in the squabbles over the inheritance of the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. The subsequent confrontation with the armies of the Dutch Republic led to the Treaty of Xanten. The episode was in many ways a rehearsal of what was to come in the Thirty Years' War. After the defenestration of Prague, Albert responded by sending troops to his cousin Ferdinand II and by pressing Philip III for financial support to the cause of the Austrian Habsburgs. As such he contributed considerably to the victory of the Habsburg and Bavarian forces in the Battle of the White Mountain on 8 November 1620.

Death and succession

_Funeral_procession_for_Albert_VII%252C_Archduke_of_Austria.jpg.webp)

Albert and Isabella Clara Eugenia had three children who died at a very young age, in 1605, 1607 and 1609. As the years passed, it became clear that they would have no more offspring. When Albert's health suffered a serious breakdown in the winter of 1613–1614, steps were taken to ensure the accession of Philip III of Spain in accordance to the Act of Cession. As a result, the States of the loyal provinces swore to accept the King as heir of the Archduke and Archduchess in a number of ceremonies between May 1616 and January 1617. Philip III however predeceased his uncle on 31 March 1621. The right to succeed the couple thereupon passed to his eldest, Philip IV.

Albert's health again deteriorated markedly in the closing months of 1620. As the Twelve Years' Truce would expire the next April, he devoted his last energies to securing its renewal. In order to reach this goal he was prepared to make far reaching concessions. Much to his frustration, neither the Spanish Monarchy, nor the Dutch Republic took his pleas for peace seriously. His death on 13 July 1621 therefore more or less coincided with the resumption of hostilities.

Artistic patronage

Virtually nothing remains of Albert and Isabella Clara Eugenia' palace on the Koudenberg in Brussels, their summer retreat in Mariemont or their hunting lodge in Tervuren. Their once magnificent collections were scattered after 1633 and considerable parts of them have been lost. Still, the Archdukes Albert and Isabella enjoy a well merited reputation as patrons of the arts. They are probably best remembered for the appointment of Peter Paul Rubens as their court painter in 1609. They likewise gave commissions to outstanding painters such as Frans Pourbus the Younger, Otto van Veen and Jan Brueghel the Elder. Less well known painters such as Hendrik de Clerck, Theodoor van Loon and Denis van Alsloot were also called upon. Mention should furthermore be made of architects such as Wenzel Cobergher and Jacob Franquart, as well as of the sculptors de Nole. By far the best preserved ensemble of art from the archducal period is to be found at Scherpenheuvel where Albert and Isabella directed Cobergher, the painter Theodoor van Loon and the de Noles to create a pilgrimage church in a planned city.

Titles

As co-sovereign of the Habsburg Netherlands, the title was: "Albert and Isabella Clara Eugenia, Infanta of Spain, by the grace of God Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Burgundy, Lothier, Brabant, Limburg, Luxembourg and Guelders, Counts of Habsburg, Flanders, Artois, Burgundy, Tyrol, Palatines in Hainaut, Holland, Zeeland, Namur and Zutphen, Margraves of the Holy Roman Empire, Lord and Lady of Frisia, Salins, Mechlin, the City, Towns and Lands of Utrecht, Overijssel and Groningen".

For use in correspondence with German princes: "The Most Serene, Highborn Prince and Lord, Lord Albert, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Lothier, Brabant, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Limburg, Luxembourg, Guelders and Württemberg, Count of Habsburg, Flanders, Tyrol, Artois, Burgundy, Palatine in Hainaut, Holland, Zeeland, Namur and Zutphen, Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire, Lord of Frisia, Salins, Mechlin, the City, Towns and Lands of Utrecht, Overijssel and Groningen".

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Albert VII, Archduke of Austria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Marek, Miroslav. "Complete Genealogy of the House of Habsburg". Genealogy.EU.

- Guilelmus van Gulik and Conradus Eubel, Hierarchia catholica medii et recentioris aevi Volumen tertium, editio altera (ed. L. Schmitz-Kallenberg) (Monasterii 1923), p. 45.

- Gulik-Eubel, p. 315.

- There was a contemporary precedent. In 1588 Cardinal Ferdinando de' Medici resigned on the death of his brother in order to become Grand Duke of Tuscany: Gulik-Eubel, p. 40 and n. 5. Ferdinand too had not taken Holy Orders.

- Caeiro (1961) p. 5-31.

- Gulik-Eubel, p. 45 note 12.

- Caeiro (1961) passim.

- Feros (2000) p. 28-30

- Morgan (1993) p. 208-210.

- "The Archdukes Albert and Isabella Visiting a Collector's Cabinet". The Walters Art Museum.

- Wurzbach, Constantin, von, ed. (1861). . Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich [Biographical Encyclopedia of the Austrian Empire] (in German). Vol. 7. p. 112 – via Wikisource.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Press, Volker (1990), "Maximilian II.", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 16, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 471–475; (full text online)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Priebatsch, Felix (1908), "Wladislaw II.", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), vol. 54, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 688–696

- Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Wurzbach, Constantin, von, ed. (1861). . Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich [Biographical Encyclopedia of the Austrian Empire] (in German). Vol. 7. p. 19 – via Wikisource.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Stephens, Henry Morse (1903). The story of Portugal. G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 125, 139, 279. ISBN 9780722224731. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

Bibliography

- Allen, Paul C. (2000). Philip III and the Pax Hispanica, 1598-1621: The Failure of Grand Strategy. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07682-7.

- Duerloo, Luc (2012). Dynasty and Piety: Archduke Albert (1598-1621) and Habsburg Dynastic Culture in an Age of Religious Wars. Ashgate. ISBN 9780754669043. online review

- Feros, Antonio (2000). Kingship and Favoritism in the Spain of Philip III, 1598–1621. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56113-2.

- Morgan, Hiram (1993). Tyrone's Rebellion: The Outbreak of the Nine Years' War in Tudor Ireland. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-86193-224-5.

Other languages

- Caeiro, Francisco (1961). O arquiduque Alberto de Áustria: Vice-rei e inquisidor-mor de Portugal, cardeal legado do papa, governador e depois soberano dos Países Baixos: Historia e arte. Neogravusa.

- Duerloo, Luc; Thomas, Werner, eds. (1998). Albrecht & Isabella, 1598–1621: Catalogus. Brepols. ISBN 2-503-50724-7.

- Thomas, Werner; Duerloo, Luc, eds. (1998). Albert & Isabella, 1598–1621: Essays. Brepols. ISBN 2-503-50726-3.

- Duerloo, Luc; Wingens, Marc (2002). Scherpenheuvel: Het Jeruzalem van de Lage Landen. Davidsfonds. ISBN 90-5826-182-4.

- Otto Brunner (1953), "Albrecht VII. (Albert)", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 1, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, p. 170; (full text online)

- Copia Ihrer Hochfurstlicher Durchleuchtigkeit des Ertz-Herzogen zu Österreich etc. Dem Furstenthumb Cleve, Graffschafft von der Marck ... Ertheilte Neutralitet. Verstegen, Cleve 1621. (digital version by the University and State Library, Düsseldorf)

External links

- Literature by and about Albert VII, Archduke of Austria in the German National Library catalogue

- 1627 illustration: Alberto Austriae Archiduci (Digitized)