Ardenwald axe murders

The Ardenwald axe murders is an unsolved mass murder that occurred in the early morning of June 9, 1911, in Ardenwald, Oregon, United States, then a neighboring community of Portland. The victims were the Hill family: William Hill, his wife Ruth, and Ruth's two children from a previous marriage, Philip and Dorothy. All four victims had been bludgeoned to death with an axe.

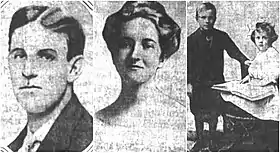

From left to right: William Hill, Ruth Hill, Philip Rintoul, and Dorothy Rintoul | |

| Date | June 9, 1911 |

|---|---|

| Time | 12:45 a.m. PT |

| Location | Ardenwald, Oregon, U.S. |

| Type | Mass murder |

| Outcome | Unsolved |

| Deaths |

|

Because both of the female victims were sexually assaulted, it was believed by authorities that the murders were motivated by sex and possibly the work of a sex maniac. Nathan Harvey, a landowner who lived adjacent to the Hills' home, was charged with their murders on December 20, 1911, but these charges were dropped one week later, and further investigation into Harvey's possible involvement was ceased in February 1912 following an inquest.

Several other suspects have been considered, including a vagrant named Edward Ramsey. In 1917, a man named William Riggin confessed to having participated in the murders, but provided significantly varied accounts that were inconsistent with one another.

Background

In the spring of 1911, William Hill (born December 19, 1878); his wife Ruth (née Cowing; born March 26, 1878); and Ruth's two children from her previous marriage, Philip Rintoul (born October 14, 1902) and Dorothy Rintoul (born June 2, 1905); moved into a cottage in the rural community of Ardenwald, Oregon, then located immediately south of Portland.[1] William had built the cottage himself, and the family moved into the home in early May of that year.[1]

On the morning of June 8, Ruth visited the law offices of her brother and father in Portland, who later stated that she seemed "disturbed about something" which she never disclosed.[1]

Murders

At approximately 8:00 a.m. on June 9,[2] the wife of C. W. Matthews, a neighbor of the Hills', knocked on the front door of their home after her husband noticed that William had not left the residence as he normally did each morning to catch the interurban streetcar to his job at the Portland Natural Gas Company.[3] Upon receiving no answer, Mrs. Matthews peeked into the front window of the home and saw the bloodied body of four-year-old Dorothy laid out on the floor.[4] Clackamas County Sheriff Ernest Mass arrived shortly after the Matthews' reported the crime.[4]

It was estimated that the murders occurred around 12:45 a.m.[5] based on a broken clock in the cabin that had stopped at the time, along with a neighbor's report that his dogs had begun barking loudly around this time.[4] The bodies of Ruth and William were discovered entangled in bed, Ruth's lying beneath that of her husband's.[4] It was determined that, after William had been bludgeoned to death with an axe, Ruth was then struck twice in the head.[4] After both parents were deceased, eight-year-old Philip was subsequently bludgeoned to death, with Dorothy being the last to die.[6]

Investigation

The bloodied axe used in the murders was left in the Hills' home, propped against the foot of Dorothy's bed.[2] It was determined by authorities that the axe did not belong to the Hills and had been stolen from the front porch of Joseph Delk, who lived approximately 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) north of the Hill residence.[1] Most of the windows of the house had been covered in cloth and garments by the perpetrator, ostensibly to conceal the crime.[2][7]

Though some jewelry was missing from the Hill residence, other valuables and money were left behind, leading Sheriff Mass to exclude robbery as a motive for the crime.[4] Because of the violent and sexual nature of the murders, Mass believed that sex was the motive and that the assailant may have been a pedophile.[4] In order to assist the investigation, Mass brought a bloodhound from Seattle to complete searches of the Hill property and surrounding area, but these efforts did not prove fruitful.[8]

A coroner who examined the bodies stated that William's injuries had left his head "completely chopped to pieces on the right side; especially on the right side above the eye, deforming [his] whole face."[2] Ruth similarly sustained a severe skull fracture that extended from above her right eye across her whole face, as well as another fracture that broke her teeth and lower jaw.[2] Dorothy had sustained several skull fractures to both the front and back of the head from an axe blade,[2] while Philip's head wounds appeared to have been inflicted with the handle of the axe.[2] Based on examination of Ruth's body, it was determined she had likely been raped after death,[9] while Dorothy had been sexually assaulted prior to her murder.[6] Bloody fingerprints were found smeared on Dorothy's body,[4] as well as on Philip's arm.[10]

Suspects

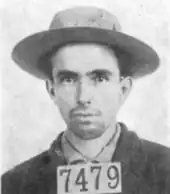

Edward Ramsey

On the morning of the Hill murders, a vagrant named Edward Ramsey was arrested at Oaks Bottom while attempting to float on a makeshift raft.[9] After his arrest, it was believed by authorities that Ramsey had been the subject of a series of complaints—spanning several years—regarding an unknown man lurking in the communities east of Portland.[9] Ramsey, a drifter, lived in the woods and subsisted by trapping animals and stealing food.[11] Though initially considered a suspect in the Hills' murders, he was ultimately cleared of suspicion.[11]

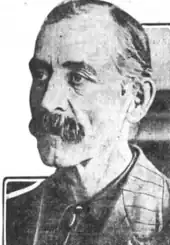

Nathan Harvey

On December 20, 1911, a 55-year-old nursery owner named Nathan Harvey, who lived 100 yards (91 m) from the Hill residence, was charged with the murders of all four victims.[12] Harvey, an Iowa native and local landowner, had been in a land dispute with William Hill prior to the murders.[13] Upon investigation, it was discovered that Harvey had already been loosely connected to various gruesome crimes: In 1894, an 18-year-old woman named Mamie Welch was murdered in a strawberry patch on Harvey's property, and her body found lying next to an adjacent road.[5] A series of other murders and mysterious deaths occurred within the Harvey family: in 1896 one of Harvey's brothers shot their mother to death before killing himself,[5] and in 1899 one of Harvey's other brothers was found drowned in a mill pond in Milwaukie.[5]

Upon questioning Harvey's neighbors in Ardenwald, Mass reported that several women told him Harvey had made "improper proposals" to them, as well as insulting them.[5] Mass subsequently stated that he had "absolute proof" that Harvey had taken the last train to Ardenwald on the interurban railway from Cazadero, which arrived in Ardenwald at 12:25 a.m. on the night of June 9.[5] Two witnesses stated they saw Harvey exit the train at Ardenwald station at this time.[5]

Despite the charges, Harvey had a large number of supporters who professed his innocence and protested his arrest.[14] On December 23 and 26, mass meetings were held in Milwaukie and Sellwood, during which over 500 signatures were gathered calling for the charges to be dropped.[15] Some locals, however, spoke out against the protests, with one anonymous landowner telling The Oregonian: "Except by his friends, Harvey is feared...There are those possessed of evidence in the case that could incriminate Harvey. If fears of possible retribution from the man are allayed I think they can be induced to tell what they know."[16]

While Mass was convinced that Harvey was behind the murders, the charges against him were ultimately dropped on December 27, 1911, pending further investigation,[17] and he was released during a preliminary hearing.[18] In February 1912, a Clackamas County judge formally closed further investigation into Harvey.[17]

William Riggin

In May 1917, William Riggin confessed to shooting William Booth in Willamina in October 1915.[19] During his confession in the killing, Riggin also claimed to have witnessed the Hills' murders along with a Mexican man who went by the nickname "Brown" and a man named William Flynn, the latter an alias of Edward Ramsey.[20] Riggin claimed to have met the men in Oregon City and that they planned a robbery scheme together, looting local homes.[19] According to Riggin, he watched outside the Hills' cottage while Brown, armed with an axe, and Flynn entered to rob the family.[19] Riggin claimed to have waited outside the cottage for approximately thirty minutes, during which he heard children screaming inside.[21] After the murders, Riggin claimed Brown and Flynn exited the cottage with approximately $1,400 worth of gold and silver.[22] For his role in the robbery, Riggin claimed to have been paid $100.[22]

Upon further questioning, Riggin changed his account of events, instead claiming in a formal statement (made July 21, 1917) to have participated in the robbery and murders with Ramsey, not the anonymous Brown and Flynn.[22] Riggins' two diverging accounts were riddled with inconsistencies regarding the Hills' cabin and other logistics.[23] Despite this, Riggin was able to point out specific locations regarding the crime, including the site of the cottage, which had been demolished after their murders.[24]

Legacy

The Ardenwald axe murders have been described by historians as one of the most brutal murders in the history of Oregon,[3] and in the enduring years became subject of local folklore.[17]

See also

References

- Thacher 1919, p. 93.

- Thacher 1919, p. 95.

- Chandler 2013, p. 78.

- Chandler 2013, p. 79.

- "Hill Suspect Human Pervert". East Oregonian. Pendleton, Oregon. December 21, 1911. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- Chandler 2013, pp. 79–80.

- Chandler 2013, pp. 80–84.

- Chandler 2013, p. 81.

- Chandler 2013, p. 80.

- Thacher 1919, pp. 95–96.

- Chandler 2013, pp. 80–81.

- "Charged With Killing Them All". The Press Democrat. Santa Rosa, California. December 21, 1911. p. 1 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- Chandler 2013, p. 83–84.

- Chandler 2013, pp. 84.

- Chandler 2013, pp. 84–85.

- Chandler 2013, p. 85.

- Chandler 2013, p. 86.

- "Grand Jury Takes Hand In Investigating Mystery". Anaconda Standard. Anaconda, Montana. February 10, 1912. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- Thacher 1919, p. 101.

- Thacher 1919, pp. 94, 101.

- Thacher 1919, pp. 101–102.

- Thacher 1919, p. 102.

- Thacher 1919, pp. 102–105.

- Thacher 1919, p. 106.

Sources

- Chandler, J. D. (2013). Murder & Mayhem in Portland, Oregon. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-609-49925-9.

- James, Bill; James, Rachel McCarthy (2017). The Man from the Train: The Solving of a Century-Old Serial Killer Mystery. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-476-79625-3.

- Thacher, George (1919). Why Some Men Kill; Or, Murder Mysteries Revealed. Portland, Oregon: Press of Pacific Coast Rescue and Protective Society. OCLC 36275094.