Arithmetic

Arithmetic (from Ancient Greek ἀριθμός (arithmós) 'number', and τική [τέχνη] (tikḗ [tékhnē]) 'art, craft') is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers—addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th century, Italian mathematician Giuseppe Peano formalized arithmetic with his Peano axioms, which are highly important to the field of mathematical logic today.

History

The prehistory of arithmetic is limited to a small number of artifacts that may indicate the conception of addition and subtraction; the best-known is the Ishango bone from central Africa, dating from somewhere between 20,000 and 18,000 BC, although its interpretation is disputed.[1]

The earliest written records indicate the Egyptians and Babylonians used all the elementary arithmetic operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, as early as 2000 BC. These artifacts do not always reveal the specific process used for solving problems, but the characteristics of the particular numeral system strongly influence the complexity of the methods. The hieroglyphic system for Egyptian numerals, like the later Roman numerals, descended from tally marks used for counting. In both cases, this origin resulted in values that used a decimal base but did not include positional notation. Complex calculations with Roman numerals required the assistance of a counting board (or the Roman abacus) to obtain the results.

Early number systems that included positional notation were not decimal; these include the sexagesimal (base 60) system for Babylonian numerals and the vigesimal (base 20) system that defined Maya numerals. Because of the place-value concept, the ability to reuse the same digits for different values contributed to simpler and more efficient methods of calculation.

The continuous historical development of modern arithmetic starts with the Hellenistic period of ancient Greece; it originated much later than the Babylonian and Egyptian examples. Prior to the works of Euclid around 300 BC, Greek studies in mathematics overlapped with philosophical and mystical beliefs. Nicomachus is an example of this viewpoint, using the earlier Pythagorean approach to numbers and their relationships to each other in his work, Introduction to Arithmetic.

Greek numerals were used by Archimedes, Diophantus, and others in a positional notation not very different from modern notation. The ancient Greeks lacked a symbol for zero until the Hellenistic period, and they used three separate sets of symbols as digits: one set for the units place, one for the tens place, and one for the hundreds. For the thousands place, they would reuse the symbols for the units place, and so on. Their addition algorithm was identical to the modern method, and their multiplication algorithm was only slightly different. Their long division algorithm was the same, and the digit-by-digit square root algorithm, popularly used as recently as the 20th century, was known to Archimedes (who may have invented it). He preferred it to Hero's method of successive approximation because, once computed, a digit does not change, and the square roots of perfect squares, such as 7485696, terminate immediately as 2736. For numbers with a fractional part, such as 546.934, they used negative powers of 60 instead of negative powers of 10 for the fractional part 0.934.[2]

The ancient Chinese had advanced arithmetic studies dating from the Shang Dynasty and continuing through the Tang Dynasty, from basic numbers to advanced algebra. The ancient Chinese used a positional notation similar to that of the Greeks. Since they also lacked a symbol for zero, they had one set of symbols for the units place and a second set for the tens place. For the hundreds place, they then reused the symbols for the units place, and so on. Their symbols were based on ancient counting rods. The exact time when the Chinese started calculating with positional representation is unknown, though it is known that the adoption started before 400 BC.[3] The ancient Chinese were the first to meaningfully discover, understand, and apply negative numbers. This is explained in the Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art (Jiuzhang Suanshu), which was written by Liu Hui and dates back to the 2nd century BC.

The gradual development of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system independently devised the place-value concept and positional notation, which combined the simpler methods for computations with a decimal base and the use of a digit representing 0. This allowed the system to consistently represent both large and small integers—an approach that eventually replaced all other systems. In the early 6th century AD, the Indian mathematician Aryabhata incorporated an existing version of this system into his work and experimented with different notations. In the 7th century, Brahmagupta established the use of 0 as a separate number and determined the results for multiplication, division, addition, and subtraction of zero and all other numbers—except for the result of division by zero. His contemporary, the Syriac bishop Severus Sebokht (650 AD) said, "Indians possess a method of calculation that no word can praise enough. Their rational system of mathematics, or of their method of calculation. I mean the system using nine symbols."[4] The Arabs also learned this new method and called it hesab.

Although the Codex Vigilanus described an early form of Arabic numerals (omitting 0) by 976 AD, Leonardo of Pisa (Fibonacci) was primarily responsible for spreading their use throughout Europe after the publication of his book Liber Abaci in 1202. He wrote, "The method of the Indians (Latin Modus Indorum) surpasses any known method to compute. It's a marvelous method. They do their computations using nine figures and symbol zero".[5]

In the Middle Ages, arithmetic was one of the seven liberal arts taught in universities.

The flourishing of algebra in the medieval Islamic world, and also in Renaissance Europe, was an outgrowth of the enormous simplification of computation through decimal notation.

Various types of tools have been invented and widely used to assist in numeric calculations. Before Renaissance, they were various types of abaci. More recent examples include slide rules, nomograms and mechanical calculators, such as Pascal's calculator. At present, they have been supplanted by electronic calculators and computers.

Arithmetic operations

The basic arithmetic operations are addition, subtraction, multiplication and division, although arithmetic also includes more advanced operations, such as manipulations of percentages,[6] square roots, exponentiation, logarithmic functions, and even trigonometric functions, in the same vein as logarithms (prosthaphaeresis). Arithmetic expressions must be evaluated according to the intended sequence of operations. There are several methods to specify this, either—most common, together with infix notation—explicitly using parentheses and relying on precedence rules, or using a prefix or postfix notation, which uniquely fix the order of execution by themselves. Any set of objects upon which all four arithmetic operations (except division by zero) can be performed, and where these four operations obey the usual laws (including distributivity), is called a field.[7]

Addition

Addition, denoted by the symbol , is the most basic operation of arithmetic. In its simple form, addition combines two numbers, the addends or terms, into a single number, the sum of the numbers (such as 2 + 3 = 5 or 3 + 5 = 8).

Adding finitely many numbers can be viewed as repeated simple addition; this procedure is known as summation, a term also used to denote the definition for "adding infinitely many numbers" in an infinite series. Repeated addition of the number 1 is the most basic form of counting; the result of adding 1 is usually called the successor of the original number.

Addition is commutative and associative, so the order in which finitely many terms are added does not matter.

The number 0 has the property that, when added to any number, it yields that same number; so, it is the identity element of addition, or the additive identity.

For every number x, there is a number denoted –x, called the opposite of x, such that x + (–x) = 0 and (–x) + x = 0. So, the opposite of x is the inverse of x with respect to addition, or the additive inverse of x. For example, the opposite of 7 is −7, since 7 + (−7) = 0.

Addition can also be interpreted geometrically, as in the following example. If we have two sticks of lengths 2 and 5, then, if the sticks are aligned one after the other, the length of the combined stick becomes 7, since 2 + 5 = 7.

Subtraction

Subtraction, denoted by the symbol , is the inverse operation to addition. Subtraction finds the difference between two numbers, the minuend minus the subtrahend: D = M − S. Resorting to the previously established addition, this is to say that the difference is the number that, when added to the subtrahend, results in the minuend: D + S = M.[8]

For positive arguments M and S holds:

- If the minuend is larger than the subtrahend, the difference D is positive.

- If the minuend is smaller than the subtrahend, the difference D is negative.

In any case, if minuend and subtrahend are equal, the difference D = 0.

Subtraction is neither commutative nor associative. For that reason, the construction of this inverse operation in modern algebra is often discarded in favor of introducing the concept of inverse elements (as sketched under § Addition), where subtraction is regarded as adding the additive inverse of the subtrahend to the minuend, that is, a − b = a + (−b). The immediate price of discarding the binary operation of subtraction is the introduction of the (trivial) unary operation, delivering the additive inverse for any given number, and losing the immediate access to the notion of difference, which is potentially misleading when negative arguments are involved.

For any representation of numbers, there are methods for calculating results, some of which are particularly advantageous in exploiting procedures, existing for one operation, by small alterations also for others. For example, digital computers can reuse existing adding-circuitry and save additional circuits for implementing a subtraction, by employing the method of two's complement for representing the additive inverses, which is extremely easy to implement in hardware (negation). The trade-off is the halving of the number range for a fixed word length.

A formerly widespread method to achieve a correct change amount, knowing the due and given amounts, is the counting up method, which does not explicitly generate the value of the difference. Suppose an amount P is given in order to pay the required amount Q, with P greater than Q. Rather than explicitly performing the subtraction P − Q = C and counting out that amount C in change, money is counted out starting with the successor of Q, and continuing in the steps of the currency, until P is reached. Although the amount counted out must equal the result of the subtraction P − Q, the subtraction was never really done and the value of P − Q is not supplied by this method.

Multiplication

Multiplication, denoted by the symbols or , is the second basic operation of arithmetic. Multiplication also combines two numbers into a single number, the product. The two original numbers are called the multiplier and the multiplicand, mostly both are called factors.

Multiplication may be viewed as a scaling operation. If the numbers are imagined as lying in a line, multiplication by a number greater than 1, say x, is the same as stretching everything away from 0 uniformly, in such a way that the number 1 itself is stretched to where x was. Similarly, multiplying by a number less than 1 can be imagined as squeezing towards 0, in such a way that 1 goes to the multiplicand.

Another view on multiplication of integer numbers (extendable to rationals but not very accessible for real numbers) is by considering it as repeated addition. For example. 3 × 4 corresponds to either adding 3 times a 4, or 4 times a 3, giving the same result. There are different opinions on the advantageousness of these paradigmata in math education.

Multiplication is commutative and associative; further, it is distributive over addition and subtraction. The multiplicative identity is 1, since multiplying any number by 1 yields that same number. The multiplicative inverse for any number except 0 is the reciprocal of this number, because multiplying the reciprocal of any number by the number itself yields the multiplicative identity 1. 0 is the only number without a multiplicative inverse, and the result of multiplying any number and 0 is again 0. One says that 0 is not contained in the multiplicative group of the numbers.

The product of a and b is written as a × b or a·b. It can also written by simple juxtaposition: ab. In computer programming languages and software packages (in which one can only use characters normally found on a keyboard), it is often written with an asterisk: a * b.

Algorithms implementing the operation of multiplication for various representations of numbers are by far more costly and laborious than those for addition. Those accessible for manual computation either rely on breaking down the factors to single place values and applying repeated addition, or on employing tables or slide rules, thereby mapping multiplication to addition and vice versa. These methods are outdated and are gradually replaced by mobile devices. Computers use diverse sophisticated and highly optimized algorithms, to implement multiplication and division for the various number formats supported in their system.

Division

Division, denoted by the symbols or , is essentially the inverse operation to multiplication. Division finds the quotient of two numbers, the dividend divided by the divisor. Under common rules, dividend divided by zero is undefined. For distinct positive numbers, if the dividend is larger than the divisor, the quotient is greater than 1, otherwise it is less than or equal to 1 (a similar rule applies for negative numbers). The quotient multiplied by the divisor always yields the dividend.

Division is neither commutative nor associative. So as explained in § Subtraction, the construction of the division in modern algebra is discarded in favor of constructing the inverse elements with respect to multiplication, as introduced in § Multiplication. Hence division is the multiplication of the dividend with the reciprocal of the divisor as factors, that is, a ÷ b = a × 1/b.

Within the natural numbers, there is also a different but related notion called Euclidean division, which outputs two numbers after "dividing" a natural N (numerator) by a natural D (denominator): first a natural Q (quotient), and second a natural R (remainder) such that N = D×Q + R and 0 ≤ R < Q.

In some contexts, including computer programming and advanced arithmetic, division is extended with another output for the remainder. This is often treated as a separate operation, the Modulo operation, denoted by the symbol or the word , though sometimes a second output for one "divmod" operation.[9] In either case, Modular arithmetic has a variety of use cases. Different implementations of division (floored, truncated, Euclidean, etc.) correspond with different implementations of modulus.

Fundamental theorem of arithmetic

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic states that any integer greater than 1 has a unique prime factorization (a representation of a number as the product of prime factors), excluding the order of the factors. For example, 252 only has one prime factorization:

- 252 = 22 × 32 × 71

Euclid's Elements first introduced this theorem, and gave a partial proof (which is called Euclid's lemma). The fundamental theorem of arithmetic was first proven by Carl Friedrich Gauss.

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic is one of the reasons why 1 is not considered a prime number. Other reasons include the sieve of Eratosthenes, and the definition of a prime number itself (a natural number greater than 1 that cannot be formed by multiplying two smaller natural numbers.).

Decimal arithmetic

Decimal representation refers exclusively, in common use, to the written numeral system employing arabic numerals as the digits for a radix 10 ("decimal") positional notation; however, any numeral system based on powers of 10, e.g., Greek, Cyrillic, Roman, or Chinese numerals may conceptually be described as "decimal notation" or "decimal representation".

Modern methods for four fundamental operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication and division) were first devised by Brahmagupta of India. This was known during medieval Europe as "Modus Indorum" or Method of the Indians. Positional notation (also known as "place-value notation") refers to the representation or encoding of numbers using the same symbol for the different orders of magnitude (e.g., the "ones place", "tens place", "hundreds place") and, with a radix point, using those same symbols to represent fractions (e.g., the "tenths place", "hundredths place"). For example, 507.36 denotes 5 hundreds (102), plus 0 tens (101), plus 7 units (100), plus 3 tenths (10−1) plus 6 hundredths (10−2).

The concept of 0 as a number comparable to the other basic digits is essential to this notation, as is the concept of 0's use as a placeholder, and as is the definition of multiplication and addition with 0. The use of 0 as a placeholder and, therefore, the use of a positional notation is first attested to in the Jain text from India entitled the Lokavibhâga, dated 458 AD and it was only in the early 13th century that these concepts, transmitted via the scholarship of the Arabic world, were introduced into Europe by Fibonacci[10] using the Hindu–Arabic numeral system.

Algorism comprises all of the rules for performing arithmetic computations using this type of written numeral. For example, addition produces the sum of two arbitrary numbers. The result is calculated by the repeated addition of single digits from each number that occupies the same position, proceeding from right to left. An addition table with ten rows and ten columns displays all possible values for each sum. If an individual sum exceeds the value 9, the result is represented with two digits. The rightmost digit is the value for the current position, and the result for the subsequent addition of the digits to the left increases by the value of the second (leftmost) digit, which is always one (if not zero). This adjustment is termed a carry of the value 1.

The process for multiplying two arbitrary numbers is similar to the process for addition. A multiplication table with ten rows and ten columns lists the results for each pair of digits. If an individual product of a pair of digits exceeds 9, the carry adjustment increases the result of any subsequent multiplication from digits to the left by a value equal to the second (leftmost) digit, which is any value from 1 to 8 (9 × 9 = 81). Additional steps define the final result.

Similar techniques exist for subtraction and division.

The creation of a correct process for multiplication relies on the relationship between values of adjacent digits. The value for any single digit in a numeral depends on its position. Also, each position to the left represents a value ten times larger than the position to the right. In mathematical terms, the exponent for the radix (base) of 10 increases by 1 (to the left) or decreases by 1 (to the right). Therefore, the value for any arbitrary digit is multiplied by a value of the form 10n with integer n. The list of values corresponding to all possible positions for a single digit is written as {..., 102, 10, 1, 10−1, 10−2, ...}.

Repeated multiplication of any value in this list by 10 produces another value in the list. In mathematical terminology, this characteristic is defined as closure, and the previous list is described as closed under multiplication. It is the basis for correctly finding the results of multiplication using the previous technique. This outcome is one example of the uses of number theory.

Compound unit arithmetic

Compound[11] unit arithmetic is the application of arithmetic operations to mixed radix quantities such as feet and inches; gallons and pints; pounds, shillings and pence; and so on. Before decimal-based systems of money and units of measure, compound unit arithmetic was widely used in commerce and industry.

Basic arithmetic operations

The techniques used in compound unit arithmetic were developed over many centuries and are well documented in many textbooks in many different languages.[12][13][14][15] In addition to the basic arithmetic functions encountered in decimal arithmetic, compound unit arithmetic employs three more functions:

- Reduction, in which a compound quantity is reduced to a single quantity—for example, conversion of a distance expressed in yards, feet and inches to one expressed in inches.[16]

- Expansion, the inverse function to reduction, is the conversion of a quantity that is expressed as a single unit of measure to a compound unit, such as expanding 24 oz to 1 lb 8 oz.

- Normalization is the conversion of a set of compound units to a standard form—for example, rewriting "1 ft 13 in" as "2 ft 1 in".

Knowledge of the relationship between the various units of measure, their multiples and their submultiples forms an essential part of compound unit arithmetic.

Principles of compound unit arithmetic

There are two basic approaches to compound unit arithmetic:

- Reduction–expansion method where all the compound unit variables are reduced to single unit variables, the calculation performed and the result expanded back to compound units. This approach is suited for automated calculations. A typical example is the handling of time by Microsoft Excel where all time intervals are processed internally as days and decimal fractions of a day.

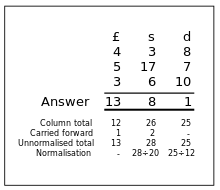

- On-going normalization method in which each unit is treated separately and the problem is continuously normalized as the solution develops. This approach, which is widely described in classical texts, is best suited for manual calculations. An example of the ongoing normalization method as applied to addition is shown below.

The addition operation is carried out from right to left; in this case, pence are processed first, then shillings followed by pounds. The numbers below the "answer line" are intermediate results.

The total in the pence column is 25. Since there are 12 pennies in a shilling, 25 is divided by 12 to give 2 with a remainder of 1. The value "1" is then written to the answer row and the value "2" carried forward to the shillings column. This operation is repeated using the values in the shillings column, with the additional step of adding the value that was carried forward from the pennies column. The intermediate total is divided by 20 as there are 20 shillings in a pound. The pound column is then processed, but as pounds are the largest unit that is being considered, no values are carried forward from the pounds column.

For the sake of simplicity, the example chosen did not have farthings.

Operations in practice

During the 19th and 20th centuries various aids were developed to aid the manipulation of compound units, particularly in commercial applications. The most common aids were mechanical tills which were adapted in countries such as the United Kingdom to accommodate pounds, shillings, pence and farthings, and ready reckoners, which are books aimed at traders that catalogued the results of various routine calculations such as the percentages or multiples of various sums of money. One typical booklet[17] that ran to 150 pages tabulated multiples "from one to ten thousand at the various prices from one farthing to one pound".

The cumbersome nature of compound unit arithmetic has been recognized for many years—in 1586, the Flemish mathematician Simon Stevin published a small pamphlet called De Thiende ("the tenth")[18] in which he declared the universal introduction of decimal coinage, measures, and weights to be merely a question of time. In the modern era, many conversion programs, such as that included in the Microsoft Windows 7 operating system calculator, display compound units in a reduced decimal format rather than using an expanded format (e.g., "2.5 ft" is displayed rather than "2 ft 6 in").

Number theory

Until the 19th century, number theory was a synonym of "arithmetic". The addressed problems were directly related to the basic operations and concerned primality, divisibility, and the solution of equations in integers, such as Fermat's Last Theorem. It appeared that most of these problems, although very elementary to state, are very difficult and may not be solved without very deep mathematics involving concepts and methods from many other branches of mathematics. This led to new branches of number theory such as analytic number theory, algebraic number theory, Diophantine geometry and arithmetic algebraic geometry. Wiles' proof of Fermat's Last Theorem is a typical example of the necessity of sophisticated methods, which go far beyond the classical methods of arithmetic, for solving problems that can be stated in elementary arithmetic.

Arithmetic in education

Primary education in mathematics often places a strong focus on algorithms for the arithmetic of natural numbers, integers, fractions, and decimals (using the decimal place-value system). This study is sometimes known as algorism.

The difficulty and unmotivated appearance of these algorithms has long led educators to question this curriculum, advocating the early teaching of more central and intuitive mathematical ideas. One notable movement in this direction was the New Math of the 1960s and 1970s, which attempted to teach arithmetic in the spirit of axiomatic development from set theory, an echo of the prevailing trend in higher mathematics.[19]

Also, arithmetic was used by Islamic Scholars in order to teach application of the rulings related to Zakat and Irth. This was done in a book entitled The Best of Arithmetic by Abd-al-Fattah-al-Dumyati.[20] The book begins with the foundations of mathematics and proceeds to its application in the later chapters.

See also

Related topics

- Addition of natural numbers

- Additive inverse

- Arithmetic coding

- Arithmetic mean

- Arithmetic number

- Arithmetic progression

- Arithmetic properties

- Associativity

- Commutativity

- Distributivity

- Elementary arithmetic

- Finite field arithmetic

- Geometric progression

- Integer

- List of important publications in mathematics

- Lunar arithmetic

- Mental calculation

- Number line

- Plant arithmetic

Notes

- Rudman, Peter Strom (2007). How Mathematics Happened: The First 50,000 Years. Prometheus Books. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-59102-477-4.

- The Works of Archimedes, Chapter IV, Arithmetic in Archimedes, edited by T.L. Heath, Dover Publications Inc, New York, 2002.

- Joseph Needham, Science and Civilization in China, Vol. 3, p. 9, Cambridge University Press, 1959.

- Nau, François (1929). "Le traité sur les «constellations» écrit, en 661, par Sévère Sébokt Évèque de Qennesrin". Revue de l'Orient Chretien. Ser. 3. 7: 327–338.

- Leonardo of Pisa (2003). Fibonacci's Liber Abaci. Translated by Sigler, Laurence. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0079-3. ISBN 9780387407371.

- "Definition of Arithmetic". mathsisfun.com. Archived from the original on 2020-12-31. Retrieved 2020-08-25.

- Tapson, Frank (1996). The Oxford Mathematics Study Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-914551-2.

- "Arithmetic". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-08-25.

- "Python divmod() Function". W3Schools. Refsnes Data. Archived from the original on 2021-03-13. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- Leonardo Pisano – p. 3: "Contributions to number theory" Archived 2008-06-17 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2006. Retrieved 18 September 2006.

- Walkingame, Francis (1860). The Tutor's Companion; or, Complete Practical Arithmetic (PDF). Webb, Millington & Co. pp. 24–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-04.

- Palaiseau, JFG (October 1816). Métrologie universelle, ancienne et moderne: ou rapport des poids et mesures des empires, royaumes, duchés et principautés des quatre parties du monde [Universal, ancient and modern metrology: or report of weights and measurements of empires, kingdoms, duchies and principalities of all parts of the world] (in French). Bordeaux. Archived from the original on September 26, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- Jacob de Gelder (1824). Allereerste Gronden der Cijferkunst [Introduction to Numeracy] (in Dutch). 's-Gravenhage and Amsterdam: de Gebroeders van Cleef. pp. 163–176. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- Malaisé, Ferdinand (1842). Theoretisch-Praktischer Unterricht im Rechnen für die niederen Classen der Regimentsschulen der Königl. Bayer. Infantrie und Cavalerie [Theoretical and practical instruction in arithmetic for the lower classes of the Royal Bavarian Infantry and Cavalry School] (in German). Munich. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- "Arithmetick". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Edinburgh: A. Bell and C. Macfarquhar. 1771. pp. 365–423.

- Walkingame, Francis (1860). "The Tutor's Companion; or, Complete Practical Arithmetic" (PDF). Webb, Millington & Co. pp. 43–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-04.

- Thomson, J (1824). The Ready Reckoner in miniature containing accurate table from one to the thousand at the various prices from one farthing to one pound. Montreal. ISBN 978-0665947063. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (January 2004), "Arithmetic", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Mathematically Correct: Glossary of Terms

- al-Dumyati, Abd-al-Fattah Bin Abd-al-Rahman al-Banna (1887). "The Best of Arithmetic". World Digital Library (in Arabic). Retrieved 30 June 2013.

References

- Cunnington, Susan, The Story of Arithmetic: A Short History of Its Origin and Development, Swan Sonnenschein, London, 1904

- Dickson, Leonard Eugene, History of the Theory of Numbers (3 volumes), reprints: Carnegie Institute of Washington, Washington, 1932; Chelsea, New York, 1952, 1966

- Euler, Leonhard, Elements of Algebra, Tarquin Press, 2007

- Fine, Henry Burchard (1858–1928), The Number System of Algebra Treated Theoretically and Historically, Leach, Shewell & Sanborn, Boston, 1891

- Karpinski, Louis Charles (1878–1956), The History of Arithmetic, Rand McNally, Chicago, 1925; reprint: Russell & Russell, New York, 1965

- Ore, Øystein, Number Theory and Its History, McGraw–Hill, New York, 1948

- Weil, André, Number Theory: An Approach through History, Birkhauser, Boston, 1984; reviewed: Mathematical Reviews 85c:01004

External links

- MathWorld article about arithmetic

- The New Student's Reference Work/Arithmetic (historical)

- The Great Calculation According to the Indians, of Maximus Planudes – an early Western work on arithmetic at Convergence

- Weyde, P. H. Vander (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.